Volume 14

Direct Human Service Experience and Its Effect on

Volunteers' Self-Perceived Generosity and Meeting Volunteer Expectations

Emily M. Borger

Olivet Nazarene University

Key Words: Direct human service, volunteer, expectations, generosity, appreciation, satisfaction, value, recruitment

Abstract

A study using participants (n=61) from a small liberal arts college was conducted to analyze the effect of direct human service on volunteers' self-perceived generosity, expected versus actual appreciation, expected versus actual satisfaction in work, and expected versus actual value of work. An experimental group (n=31) was given pre- and post-surveys evaluating these dependent variables before and after treatment of participation in direct human service at a free community lunch program and was compared to a control group (n=30). It was found that there was a significant difference in the reported self-perception of generosity in the pre-surveys between the control group (M=15.17) and experimental group (M=16.52), t(59) =-2.02, p<.05, in the expected satisfaction between the control (M=15.40) and experimental (M=18.61) groups, t(59) = -4.48, p<.01, in actual satisfaction between the control (M=16.53) and experimental (M=19.17) groups, t(58) = -3.53, p<.01, between the expected value of work in the control group (M=10.33) and the experimental groups (M=12.29), t(59) = -3.91, p<.01, and between the actual value of work between the control group (M=9.73) and the experimental group (M=12.35), t(59) = -4.26, p<.01. These results indicate higher expectations from people who were engaged in direct human service compared to controls and higher values of satisfaction and value in work after service compared to controls, which may lead them back to service in the future.

Introduction

People of all backgrounds and personalities feel a desire to serve. Service is sought out and completed because of various reasons in each person. Many reasons for serving are for personal gain or because an individual is looking for fulfillment in some area of life. If individuals have a poor experience they may be discouraged and stop volunteering. Organizations rely on volunteers, and a poor experience could discourage them from continuing in this role, detracting from the organization's productivity. If organizations are experiencing a decrease in individuals who are willing to volunteer, it may be beneficial for organizations to mentally prepare their volunteers for service through orientation so that volunteers do not have false expectations for their service. It may also be beneficial for organizations to be familiar with volunteers' expectations for service so that these conditions for service may be met.

The purpose of this study was to investigate volunteers' expectation for their direct human service experience in order to see if their expectations were met once the volunteer experience was completed. Direct human service is operationally defined in this study as service in which the volunteer interacts with those they are serving. Self-perceived generosity was also compared from before and after the volunteer experience. Student participants from a small liberal arts university in the Midwest served lunch to an underserved population who attended a free lunch program. Through pre- and post- surveys this research examined whether volunteers' self-perceived generosity and expectation of service (i.e. value of work, satisfaction in work, and appreciation received) were different from before serving to how they felt after serving.

Review of Literature

The term serve means to act as a servant, or one who expresses submission, recognizance, or debt to another. A person in this role acts as if the one he or she is doing work for owes them nothing. It is a job that is only outward and without expectance. To volunteer is to do charitable or helpful work without pay. The word volunteer also implies that the one volunteering is not expecting something in return (Farlex, n.d.). However, in our world today, the terms serve and volunteer are used frequently without being supported by selfless motivations. Motivations are often more self-centered.

People serve or volunteer for various reasons; to feel good about themselves, to make a difference, to show thanks, to share and maintain skills, to gain skills or experiences, to feel accomplished, or to live out faith (Fader, 2010). Experienced people in the field of volunteering have joined the force for reasons, on one end of the spectrum, that seek to fill a dissatisfaction in life, as Levinson (2010) stated as his initial reason to volunteer. Others, on a different note, join because of their duty to live out a calling for their faith, as Hybels (2004) made as a case for which to serve.

Other people seek to have an adventure that includes volunteering. Grout (2009) and McMillon, Cutchins, and Geissinger (2012) presented an array of volunteer vacations: opportunities around the world for people to plan a vacation while simultaneously serving others. These are ways people can gain new perspectives, maintain personal skills, add excitement to a trip, and know they have made a difference while on vacation.

The RGK Center for Philanthropy and Community Service (n.d.) promotes volunteerism through research and initiatives, encouraging people to volunteer by indicating that volunteering is not just done for charity and that it can be considered an exchange. The RGK Center offers a list of reasons to volunteer that are all self-benefitting. People should give time and resources by volunteering and receive something for themselves. Another aspect of volunteering is service learning. This aspect seeks to further the education of students and grow the institution, faculty, and students (Eyler, Giles, Stenson, & Gray, 2001). Service in this regard is done to help others while at the same time growing one's self. Through all of these resources that promote volunteering, a common theme existed in many; that of seeking some sort of self-benefit. May these resources that present a partly self-centered version of service create high expectations among volunteers that cannot be met?

Research studies have been completed to look into the motivation behind volunteers' work and the maintaining of volunteers. Hellman and House (2006) discussed research that pointed to a volunteer process for involvement. Generally sustained volunteering requires satisfaction, commitment to the organization, intent to remain serving, a helpful personality, motivation to serve, and social support. Hellman and House conducted a quantitative study using a mailed survey to look into the attitudes of rape crisis volunteers. They used 28 volunteers who had served at a rape crisis center for an average of over 5 years. Through the administration of a survey that used a Likert scale for response, Hellman and House assessed commitment to organization, value of monthly meetings, perceived self-efficacy, social support, and victim blaming. It was found, after analyzing the responses, that social support and monthly training contributed to satisfaction, and satisfaction and commitment were positively correlated with intent to remain as a volunteer for the organization.

Cloyes, Wold, Berry, and Supiano (2013) conducted a qualitative study using surveys administered to 75 inmate hospice volunteers in Louisiana. These volunteers were serving the fast-growing population in the US prison system: aging inmates. These prisoners suffer medical health conditions and are not a generally healthy group. A system for end-of-life hospice care provides an opportunity for volunteer inmates to care for and give time to the aging population in the prisons. The authors looked into beliefs and attitudes of volunteers, motivation for volunteering, what the volunteer job meant to them, and interpreted the results to develop a social theory. Because this was a qualitative study with open-ended survey questions, the responses were coded so that results could be analyzed. The responses given showed that the inmate volunteers were reshaping their identity and social-perception and also thought of volunteering as bringing value to life. This study brought emphasis to the topic of motivation to serve and indicated that behind volunteering there is often a personal desire or benefit.

Meals on Wheels is a far-reaching organization that serves meals to the elderly at their homes. The problems involved with Meals on Wheels are that there is a long waiting list for receiving meals and there are not enough volunteers to meet these requests. Buys, Marlin, Robinson, Hamlin, and Locher (2010) conducted a qualitative and evaluative study that evaluated a project that was used to recruit volunteers from faith-based communities. About 50 volunteers were drawn from faith communities in the Birmingham area. These individuals received training to become volunteers within the Meals on Wheels program. As a result of this training session, six teams were formed to serve a new route in Birmingham. The authors found that their method of recruiting volunteers from faith-based communities to increase volunteer numbers was effective in gaining volunteer support for the organization. The authors concluded that organizations should partner with other pre-existing networks in the community to increase volunteer support. People are more likely to volunteer if someone they trust is also volunteering and if they have social support.

These studies indicated that there are a multitude of reasons that people get involved with volunteering and service. Much of the literature demonstrated that society seeks to gain something from service. Cnaan and Goldberg-Glen (1991) discovered through their research that people only continue to volunteer when there is reward or when their need for satisfaction is met. The abundance of resources available for people who have an interest in serving indicates that volunteers are motivated through reasons that are ultimately self-fulfilling. It is possible that because of this style of motivation, people have expectations for their service. If volunteers come to serve widely for reasons that benefit self, does service have the ability to satisfy their expectations? To what extent does direct human service meet volunteers' expectations for satisfaction, value of work, and appreciation? This research project focused on identifying whether or not volunteer expectations were met during a direct human service experience and whether there was a change in volunteers' self-perceived generosity once service was completed.

Methods

Volunteers were recruited for this quantitative study from psychology and family and consumer science courses at a small university in the Midwest. Two different recruiting sign-up sheets were distributed in undergraduate classes. The researcher explained the voluntary opportunity to participate in research and receive extra credit as an incentive for participation. The two sign-up sheets, one for the experimental group and one for the control group, were designed to look like two separate experiments so that students did not make a connection between the two groups. Thirty-one students volunteered for the experimental group, and 30 students volunteered for the control group. The treatment for the experimental group involved serving for one to two hours at a community free lunch program. A qualification for participating in the experimental group was that the participants could not have volunteered at the specific community free lunch program previously. All volunteers were first-time volunteers at this location.

All participants took a pre-survey, ranking on a Likert scale of one to seven different characteristics about themselves and expectations they had for appreciation, satisfaction, and value of work. The control group filled the survey out in relation to their day in general (See Appendix A), while the experimental group filled the survey out in relation to expectations for their service opportunity at the community free lunch program (See Appendix B). The control group then filled out a post-survey at the end of that day, ranking the same personal characteristics and whether their expectations were met throughout the day (See Appendix C). The experimental group participants filled out the post-survey, ranking the same characteristics and expectations in relation to the service opportunity, immediately after serving at the free lunch program (See Appendix D).

Survey questions were grouped, after analyzing reliability between responses with reliability tests, into categories of self-perceived generosity, expectation of satisfaction, expectation of appreciation, and expectation of value of work. The four main dependent variables were analyzed with statistical tests including independent sample t-tests, paired sample t-tests, and repeated measures tests. Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) was used to analyze data.

Results

The purpose of this research study was to examine the effect that direct human service has on volunteers' self-perceived generosity before versus after they serve and to measure expectations for appreciation, satisfaction, and value of work that volunteers have for service and whether or not these expectations were met. It was hypothesized that the treatment of direct human service between pre- and post-surveys would cause a significant decrease in volunteers' self-perceived generosity, and a decrease in their actual versus expected appreciation, satisfaction, and value of work.

Table 1. Cronbach's Alpha Reliability Statistics

| Items Grouped | Characteristic Tested |

Cronbach's Alpha (≥ .7 indicates reliability among responses) |

Q1, Q2, Q3 Before |

Self-perceived Generosity |

.617 |

Q1, Q2, Q3 After |

Self-perceived Generosity |

.787 |

Q5, Q6, Q7 Before |

Expectation for Satisfaction |

.902 |

Q5, Q6, Q7 |

After Actual Satisfaction |

.916 |

Q8, Q9 Before |

Expectation of Appreciation |

.689 |

Q8, Q9 After |

Actual Appreciation |

.845 |

Q10, Q11 Before |

Expectation for Value of Work |

.879 |

Q10, Q11 After |

Actual Value of Work |

.922 |

Survey items (see Appendices A, B, C, & D) that examined the same variable were analyzed for reliability using the Cronbach's Alpha reliability statistic. All items that were grouped had a Cronbach's Alpha value of ≥.7, indicating strong reliability in responses, except for two groupings, as noted in Table 1. However, these items were further examined with item analyses and were considered reliable groupings. Item four, measuring overall satisfaction in life, was discarded because it did not analyze expectation versus outcome.

Dependent variables were analyzed using within-subjects-between-subjects statistical tests. Variables were analyzed between the control group (n=30) and the experimental group (n=31) and within each group from the pre-surveys and the post-surveys.

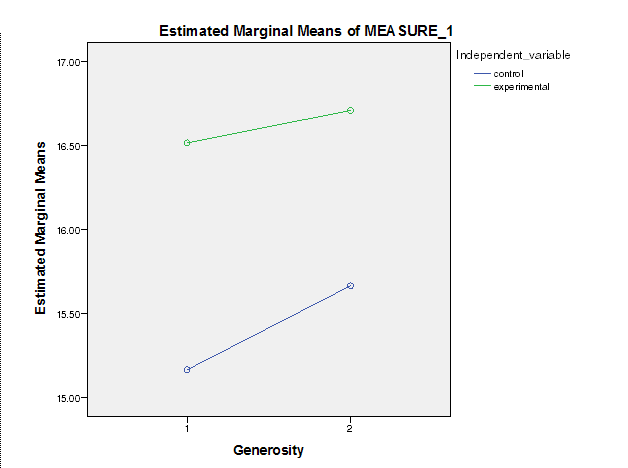

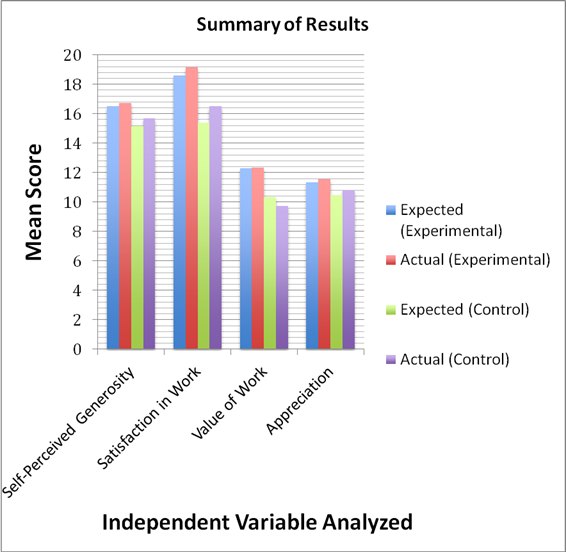

There was a significant difference in the reported pre-survey self-perceived generosity between the control group (M=15.17) and experimental group (M=16.52), t(59) =-2.02, p<.05. The experimental group believed themselves to be generally more generous before they volunteered than the control group. It was found that self-perceived generosity increased from the pre-surveys to the post-surveys in both the control group (M=15.67) and the experimental group (M=16.71), but these increases in self-perceived generosity within the two groups were not statistically significant. Although the control group was found to have a greater increase in this dependent variable than the experimental group, there was not a significant difference in self-perceived generosity between the groups in the post-surveys, t(59)=-1.66, p>.05.

Figure 1. Self-perceived generosity in pre-surveys versus post-surveys

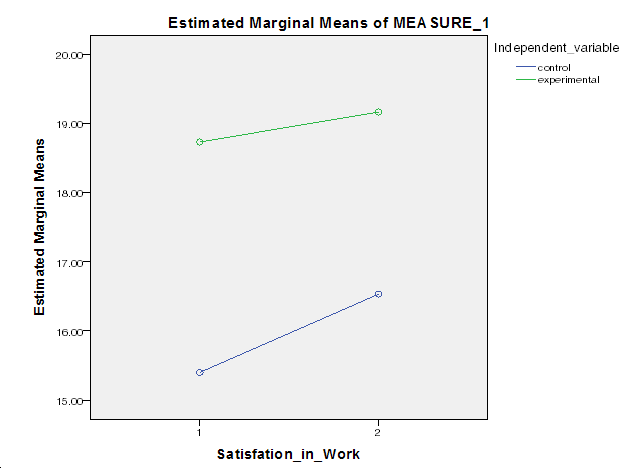

Another dependent variable measured between and within the control and experimental groups was satisfaction in work. The participants were asked to rank how satisfied they expected to be in their day, for the control group and the experimental group. There was a significant difference in the expected satisfaction between the control (M=15.40) and experimental (M=18.61) groups, t(59) = -4.48, p<.01. Those that went to volunteer at the free community lunch program had a greater expectation for satisfaction. In the post-surveys, there was also a significant difference in actual satisfaction between the control (M=16.53) and experimental (M=19.17) groups, t(58) = -3.53, p<.01. The control group ended up showing an increase from expected satisfaction (M=15.40) to actual satisfaction (M=16.53), t(29) = -3.35, p<.01. There was an increase in expected (M=18.61) versus actual (M=19.17) satisfaction in work for the experimental group, but these results were not statistically significant. The experimental group expected a greater amount of satisfaction than the control group, but there was no significant evidence to support an actual increase in satisfaction.

Figure 2. Expected versus actual satisfaction in work

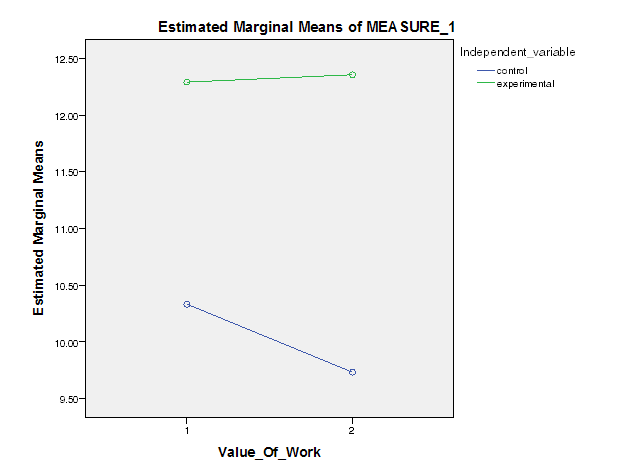

Expected versus actual value of work were analyzed within and between the control and experimental groups. Although there were no significant results within subjects, there were significant results between the expected value of work in the control group (M=10.33) and the experimental group (M=12.29), t(59) = -3.91, p<.01 and between the actual value of work between the control group (M=9.73) and the experimental group (M=12.35), t(59) = -4.26, p<.01. The experimental group anticipated their work at the free community lunch program to be more valuable than those in the control group. The experimental group also felt that their work was more valuable than the control group felt about their work. Significant increases or decreases in value of work within groups cannot be determined, but data show significant differences in both expected and actual value of work between the two groups.

Figure 3. Expected versus actual value of work

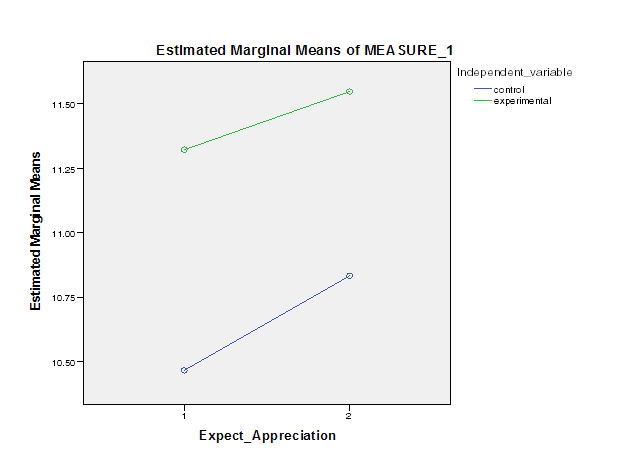

There was no significant difference in expected versus actual appreciation within or between subjects. The control group showed a greater value for actual appreciation (M=10.83) than expected appreciation (M=10.47), but this result was not statistically significant: t(29) = -.688, p = .497. The experimental group also showed a greater value of actual appreciation (M=11.55) compared with expected appreciation (M=11.32), but this was not statistically significant either: t(30) = -.535, p = .596. When comparing means of expected appreciation between the control (M=10.47) and experimental (M=11.32) groups, the values were not statistically significant: t(59) = -1.528, p = .132. Similarly, when comparing means of actual appreciation between the control (M=10.83) and experimental (M=11.55) groups, the values were not statistically significant: t(59) = -1.109, p = .272.

Figure 4. Expected versus actual appreciation

The data analyses indicated that self-perceived generosity and actual versus expected satisfaction, value of work, and appreciation did not show a significant decrease in the experimental group. Therefore, the null hypothesis was not rejected.

Figure 5. Summary of results for all variables.

Discussion

The research hypothesis stated that the treatment of direct human service between pre- and post-surveys would cause a significant decrease in volunteers' self-perceived generosity and a decrease in their actual versus expected appreciation, satisfaction, and value of work. Since the statistical data did not support this hypothesis, the null hypothesis was not rejected. However, there are significant trends and results to discuss.

In the experimental group, each expectation for service was exceeded. The mean values for actual satisfaction, value of work, and appreciation were greater than the means for expected values. Self-perceived generosity also increased from before the volunteer experience to after the experience. This is a positive result for service programs that recruit volunteers; the trend was that expected values for the four variables were exceeded by the post-survey values for the four variables. However, the increases in these values within subjects were not statistically significant.

A statistically significant trend was observed between subjects. The mean values for the control group were always lower than for the experimental groups. The control group reported significantly lower values in the pre-survey for self-perceived generosity, expectation for satisfaction, and expectation for value of work than the experimental group. This indicates that those who have the outlook of a direct human service experience have higher expectations for these variables than those who are living a typical day. The fact that many of the experimental group's post-survey values remained significantly higher than the control group indicates a fulfilling experience at the community free lunch program.

With the exception of the appreciation variable, all variables were significantly higher in the experimental group than in the control group. As mentioned previously, the experimental group had higher expectations and higher post-survey values than the control group. Past research studies by Cloyes et. al. (2013), Cnann & Goldberg (1991), and Hellman & House (2006) showed that satisfaction and value of work in volunteer experiences lead people to return to service. In these past studies, researchers concluded that satisfaction and value of work, among other variables, influenced volunteers to continue serving, but the studies do not mention appreciation as being a contributing factor to the continuation of service. In this study, appreciation was the only variable that did not show a significant difference between the control and experimental groups in post-surveys.

The results give strength to previous research. This study demonstrated that volunteers do actually receive fulfillment in satisfaction and value of work, as noted by the significant differences between the control group's and experimental group's post-survey values for satisfaction and value of work. These are two of the motivating factors that keep volunteers. Therefore, appreciation, a variable that was not mentioned in previous studies as a motivating factor for volunteers returning to service, may not have fulfilled the volunteers' expectations. There were no significant results for this variable between or within subjects. It may be significant for organizations managing volunteers to know that two of the variables drawing volunteers back to volunteering are in fact being fulfilled through the volunteer experience.

It may be significant that, while in some cases the control group made a significant increase from pre- to post-surveys, the experimental group never had a significant within group increase from pre- to post-surveys. It cannot be certain that the experimental group actually exceeded expectations they had for their service opportunity. It is true that they had significantly higher values than the control group, but not necessarily significantly higher values from their group's pre-surveys.

There are some factors that may have had an influence on this study. Time is one confounding variable that may have had an effect on the research. The control group and experimental group did not necessarily have the same amount of time between the pre- and post-surveys. The control group filled out the pre-survey at the beginning of a day, and the post-survey at the end of a day. However, the experimental group filled out the pre-survey at the beginning of a certain day and then filled out the post-survey immediately when they finished serving within a three week period of time from the pre-survey. The factors here that were held constant were that all participants in the experimental group filled out the pre-survey at the same time and filled out their post-survey directly after their volunteer experience, and all participants in the control group had a constant time between filling out their pre- and post- surveys on the same day.

A limitation to the study was that all volunteer participants volunteered at the same organization performing essentially the same job. Although this created more internal validity for the study, it decreased external validity. However, even with this limiting factor, the research results can still be applied to various other volunteer programs, as volunteer expectations and self-perceived generosity are likely to remain constant over various situations.

Another limitation to the study was that the volunteers pre-selected themselves into groups with a factor of varying amounts of extra credit. The volunteers did not know that the sign-up sheets for the control group and experimental group were for the same study; the two sign-up sheets came with a different amount of extra credit depending upon the time commitment. Therefore, the samples were not completely random. It may be beneficial for a future study to administer the survey to first-time volunteers at a location that are not volunteering for the purpose of the study and the accompanying extra credit.

Further research in this area may be completed with regard to various types of volunteer work. It would be interesting to study the difference in expectations and outcomes of direct versus indirect human service, where the volunteers may not be directly fulfilled from the experience and human interaction itself. It would also be beneficial to compare expectations and outcomes of volunteer programs that include a volunteer training session versus programs that do not provide training sessions.

The purpose of this study was to investigate volunteers' self-perceived generosity and expectation for their service experience in order to compare expectation with actual experience. Expectations for the participants of the direct human service were met through the service experience and were significantly higher than those in the control group. It is important for programs that rely on volunteers to know that their volunteers come into service with higher than usual expectations. In this case, the post-survey satisfaction, value of work, and self-perceived generosity remained significantly higher than the control group. Knowing that volunteers have expectations may encourage programs that utilize volunteers to fully train, inform, and empower them so that expectations for satisfaction and value of work can more certainly be met.

References

Buys, D. R., Marler, M. L., Robinson, C. O., Hamlin, C. M., & Locher, J. L. (2010).

Recruitment of volunteers for a home-delivered meals program serving homebound older adults: A theoretically derived programme among faith communities. Public Health Nutrition, 14(8), 1473-1478.

Cloyes, K. G, Wold, D., Berry, P. H., & Supiano, K. P. (2013). To be truly alive: Motivation among prison inmate hospice volunteers and the transformative process of end-of-life peer care service. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, 00(0), 1-14.

Cnaan, R. A. & Goldberg-Glen, R. S. (1991). Measuring motivation to volunteer in human services. Journal of applied behavioral science, 27(3).

Fader, S. (2010). 365 ideas for recruiting, retaining motivating, and rewarding your volunteers. Ocala, FL: Atlantic Publishing Group.

Farlex (n.d.). The Free Dictionary. Retrieved from www.thefreedictionary.com

Grout, P. (2009). The 100 best volunteer vacations to enrich your life. Washington DC: National Geographic Society.

Hellman, C. M., & House, D. (2006). Volunteers serving victims of sexual assault. The Journal of Social Psychology, 146(1), 117-123.

Hybels, B. (2004). The volunteer revolution. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan.

Levinson, D. T. (2010). Everyone helps, everyone wins. New York, NY: Penguin Group.

Lipp, J. L. (2009). Recruiting and managing volunteers. New York, NY: Penguin Group.

Lysakowski, L. (2005). Recruiting and training fundraising volunteers. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

McBee, S. (2002). To lead is to serve. USA: Shar McBee.

McMillon, B., Cutchins, D., & Geissinger, A. (2012). Volunteer vacations: Short term adventures that will benefit you and others (11th ed.). Chicago, IL: Chicago Review Press.

Morsch, G., & Nelson, D. (2006). The Power of Serving Others. San Francisco, CA: Berrett- Koehler.

Omoto, A. M. & Snyder, M. (1995). Sustained helping without obligation: Motivation, longevity of service, and perceived attitude change among AIDS volunteers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68(4), 671-686.

RGK Center for Philanthropy and Community Service (n.d.). Service Leader. Retrieved from www.serviceleader.org.

APPENDIX A

Control Group Pre-Survey

Initial Survey Survey Number _________

Gender

❒ Male

❒ Female

Age Group

❒ Under 18

❒ 18-25

❒ 26-40

❒ 41-55

❒ 56-65

❒ 66-75

❒ 76 or older

Race

❒ White

❒ Hispanic or Latino

❒ Black or African American

❒ Asian

❒ Pacific Islander

❒ American Indian or Alaska Native

❒ Two or more races

❒ Other

What is the highest level of education that you have completed?

❒ Less than high school

❒ High school graduate or equivalent

❒ Some college or technical training beyond high school

❒ College graduate

❒ Post-graduate or professional degree

What is your current employment status?

❒ Full-time student

❒ Part-time student

❒ Employed or self-employed full-time

❒ Employed or self-employed part-time

❒ Unemployed and looking for work

❒ Homemaker or other similar

❒ Retired and not working

In what type of area do you consider yourself to live?

❒ Rural

❒ Suburban

❒ Urban

❒ None of the above

What is your average household income level?

❒ Under $10,000

❒ $10,000-$29,999

❒ $30,000-$49,999

❒ $50,000-$69,999

❒ $70,000-$99,999

❒ $100,000-$149,999

❒ $150,000 or more

About how many hours do you spend in an average month, or in the last month, participating in direct human service or volunteer work?

❒ None

❒ More than 0, but less than 5 hours

❒ 5-10 hours

❒ 11-20 hours

❒ 21-30 hours

❒ More than 30 hours

For each of the statements below, please rate how much you agree or disagree.

7=Strongly Agree. 6=Agree. 5=Slightly agree. 4=Neither agree or disagree. 3=Slightly disagree. 2=Disagree. 1=Strongly disagree.

In general, I give generously of my time.

7 6 5 4 3 2 1

In general, I give generously of my money and resources.

7 6 5 4 3 2 1

I am someone who is quick to share what I have.

7 6 5 4 3 2 1

I am full and satisfied in life right now.

7 6 5 4 3 2 1

I believe I will feel "good" about what I have done throughout the day today.

7 6 5 4 3 2 1

I will have a sense of fulfillment after going through my day today.

7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Today will offer some sense of satisfaction.

7 6 5 4 3 2 1

I will be appreciated in some way today.

7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Someone in my life today will show me they appreciate me.

7 6 5 4 3 2 1

I will do something valuable in the lives of others today.

7 6 5 4 3 2 1

I am going to make a difference to someone today.

7 6 5 4 3 2 1

APPENDIX B

Experimental Group Pre-Survey

Initial Survey Survey Number ____________

Have you served at the Salvation Army Lunch Program before? If no, please continue the survey and research study. If yes, you may not continue in this research study. Thank you!

❒ Yes, I have served lunch at the Salvation Army Kankakee before

❒ No, I have not served lunch at the Salvation Army Kankakee before

Gender

❒ Male

❒ Female

Age Group

❒ Under 18

❒ 18-25

❒ 26-40

❒ 41-55

❒ 56-65

❒ 66-75

❒ 76 or older

Race

❒ White

❒ Hispanic or Latino

❒ Black or African American

❒ Asian

❒ Pacific Islander

❒ American Indian or Alaska Native

❒ Two or more races

❒ Other

What is the highest level of education that you have completed?

❒ Less than high school

❒ High school graduate or equivalent

❒ Some college or technical training beyond high school

❒ College graduate

❒ Post-graduate or professional degree

What is your current employment status?

❒ Full-time student

❒ Part-time student

❒ Employed or self-employed full-time

❒ Employed or self-employed part-time

❒ Unemployed and looking for work

❒ Homemaker or other similar

❒ Retired and not working

In what type of area do you consider yourself to live?

❒ Rural

❒ Suburban

❒ Urban

❒ None of the above

What is your average household income level?

❒ Under $10,000

❒ $10,000-$29,999

❒ $30,000-$49,999

❒ $50,000-$69,999

❒ $70,000-$99,999

❒ $100,000-$149,999

❒ $150,000 or more

About how many hours do you spend in an average month, or in the last month, participating in direct human service or volunteer work?

❒ None

❒ More than 0, but less than 5 hours

❒ 5-10 hours

❒ 11-20 hours

❒ 21-30 hours

❒ More than 30 hours

For each of the statements below, please rate how much you agree or disagree.

7=Strongly Agree. 6=Agree. 5=Slightly agree. 4=Neither agree or disagree. 3=Slightly disagree. 2=Disagree. 1=Strongly disagree.

In general, I give generously of my time.

7 6 5 4 3 2 1

In general, I give generously of my money and resources.

7 6 5 4 3 2 1

I am someone who is quick to share what I have.

7 6 5 4 3 2 1

I am full and satisfied in life right now.

7 6 5 4 3 2 1

After having served at the Salvation Army, I believe I will feel "good" about the work I have done.

7 6 5 4 3 2 1

I will have a sense of fulfillment after serving at the Salvation Army.

7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This serving experience will offer some sense of satisfaction.

7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The people that I serve will be appreciative of my service.

7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The people that I serve will show me that they appreciate what I did for them.

7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The work that I do today will be valuable in the lives of those I serve.

7 6 5 4 3 2 1

I believe I am going to make a difference to someone by serving at the Salvation Army

7 6 5 4 3 2 1

APPENDIX C

Control Group Post-Survey

Final Survey

For each of the statements below, please rate how much you agree or disagree.

7=Strongly Agree. 6=Agree. 5=Slightly agree. 4=Neither agree or disagree. 3=Slightly disagree. 2=Disagree. 1=Strongly disagree.

In general, I give generously of my time.

7 6 5 4 3 2 1

In general, I give generously of my money and resources.

7 6 5 4 3 2 1

I am someone who is quick to share what I have.

7 6 5 4 3 2 1

I am full and satisfied in life right now.

7 6 5 4 3 2 1

After going through my day, I feel "good" about what I did.

7 6 5 4 3 2 1

I have a sense of fulfillment after going through my day.

7 6 5 4 3 2 1

After today, I have some sense of satisfaction.

7 6 5 4 3 2 1

I was appreciated today.

7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Somebody showed me appreciation today.

7 6 5 4 3 2 1

I did something that was valuable in the lives of others today.

7 6 5 4 3 2 1

I made a difference to someone today.

7 6 5 4 3 2 1

APPENDIX D

Experimental Group Post-Survey

Final Survey Survey Number ___________

I served today at the Salvation Army Lunch Program (Please initial) _____________

For each of the statements below, please rate how much you agree or disagree.

7=Strongly Agree. 6=Agree. 5=Slightly agree. 4=Neither agree or disagree. 3=Slightly disagree. 2=Disagree. 1=Strongly disagree.

In general, I give generously of my time.

7 6 5 4 3 2 1

In general, I give generously of my money and resources.

7 6 5 4 3 2 1

I am someone who is quick to share what I have.

7 6 5 4 3 2 1

I am full and satisfied in life right now.

7 6 5 4 3 2 1

After serving today I feel "good" about the work I did.

7 6 5 4 3 2 1

I have a sense of fulfillment after serving today.

7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This serving experience offered some sense of satisfaction.

7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The people that I served were appreciative of my service.

7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The people that I served showed me that they appreciated what I did for them.

7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The work that I did today was valuable in the lives of those I served.

7 6 5 4 3 2 1

I made a difference to someone by serving today.

7 6 5 4 3 2 1

I am likely to serve at the Salvation Army lunch program again.

7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Why do you feel like you are likely or unlikely to serve here again?