|

Kappa Omicron Nu

FORUM

Application of Constructivism by Students Majoring in Early Childhood Education

Jaesook L. Gilbert

Northern Kentucky University

Abstract

According to literature (e.g., Barab & Duffy, 2000; Baxter Magolda, 2004; Brooks & Brooks, 1999; Chen, Chung, Crane, Hlavach, Pierce, & Viall, 2001; Duffy & Cunningham, 1996; Phillips, 2000), constructive education means authentic and meaningful experiences, active engagement of the learner with the learning environment, focusing on the learner not the teacher, and acknowledging (as well as challenging) learners’ understanding/intellectual development. This paper will provide an overview of how constructivism in “all of its glory” with an implementation of constructivist education pedagogy requirement is introduced to university students (hereinafter, students) enrolled in an early childhood development and program planning course. In addition, this paper will provide examples of group projects as well as address the difficulties students experience in their application of constructivist pedagogy.

Introduction

When teachers working with young children hear the term “constructivism,” they immediately focus on the “construct” portion of the term and conjure up the image of children learning by doing “hands-on” activities in their minds. According to DeVries, Demiaston, Zan, and Hildebrandt (2002), “Constructivist education takes its name from Piaget’s research showing that children actively interpret their experiences in the physical and social worlds and thus construct their own knowledge, intelligence, and morality” (p. 35). Most early childhood teachers would agree with the prior statement and categorize themselves as teachers who engage in constructivist education because of the common belief held within the early childhood field that children have to physically manipulate (i.e., “play with”) materials in order to construct their own knowledge/meaning.

Students in an early childhood development and program-planning course, the focus population for this paper, would also agree with the above paragraph and laud the benefits of a constructivist education. The feedback the author receives from student course evaluations consistently reflects that students themselves prefer to get their hands dirty or to engage in “hands-on” activities rather than sit through a lecture for the entire duration of their courses. They want to “construct” (i.e., build) their own knowledge and learning. The course evaluation comments also indicate that students prefer doing projects in the field (or the real world) because they believe they are applying what they are learning, not just hearing about it.

However, this common interpretation of the constructivist education as focusing on the direct engagement with the task or object(s) is too simple. If the teacher pre-selects choices for different centers, tells the children each step they are to follow after a teacher’s demonstration, or the teacher leaves children alone to engage in random “free” play, should one assume all of those situations are evidence of constructivism? According to literature (e.g., Barab & Duffy, 2000; Baxter Magolda, 2004; Brooks & Brooks, 1999; Chen, Chung, Crane, Hlavach, Pierce, & Viall, 2001; Duffy & Cunningham, 1996; Phillips, 2000), constructive education means authentic and meaningful experiences, active engagement of the learner with the learning environment, focusing on the learner not the teacher, and acknowledgement (as well as challenging) learners’ understanding/intellectual development. Therefore, constructivism is more than having the learner engage in “hands-on” activities or physically interact with the material(s). This paper will provide an overview of how constructivism in “all of its glory” is introduced to students enrolled in an early childhood development and program planning course. In addition, this paper will provide examples of group projects as well as address the difficulties they experience in their application of constructivist pedagogy.

Setting the Stage: Analyzing and Revisiting What Teaching Ought To Be

This particular early childhood development and program planning course focuses on theory pertinent to early childhood development and learning including constructivism, socially-mediated intelligence, multiple intelligences, and creativity. Emergent curriculum and teaching strategies reflecting social collaboration such as webbing, project work, and multimedia documentation are also emphasized. Thus, an important course objective is for students to understand the instructional implications of constructivist theory, and the ultimate goal is for the students to leave the class with a richer understanding of constructivism. That is, students should understand its learning theory principles and its pedagogy so that they can practice constructivist pedagogy, not just espouse or agree to the principles of constructivism.

In order to accomplish this course objective, child development stages and theories are reviewed at the beginning of the course. In particular, perspectives of Piaget, Vygotsky, and Dewey on a child’s development are differentiated in terms of the effect on the teacher’s classroom practice. We also introduce “social-constructivism” at this point and discuss how adding “social” to “constructivism” modifies the definition of “constructivism.” We then examine children’s play, what they learn through play, how their play reflects children’s social-cultural settings, and what teaching should be about in the field of early childhood education.

The instructor challenges students’ conception of the teacher’s role and the pedagogical implications of those conceptions by introducing the notion of the “teacher as a reflective thinker and teacher-researcher” (Hill, Stremmel, & Fu, 2005). We talk about the traditional image of the teacher as the person with all of the answers and how the teacher is supposed to teach what s/he knows to children. When the question, “Is it okay for a teacher to not know or have the answer?” is posed, students respond in the affirmative as long as the teacher finds out the answer and tells the answer to the children afterward. When the question of whether the teacher can learn from the children arises, again the students all reply in the affirmative; however, the evidence constitutes responses such as being able to see something familiar in a new way (i.e., through a child’s eyes) when requested to provide examples of what can be learned from the children.

Next, the topic of children’s competence is explored with the students by asking them whether they believe in children’s competency and to provide examples of children’s competence. The typical examples provided by students are children’s skills, such as being able to talk, read, or ride a bicycle. At this point, the Reggio Emilia (Wurm, 2005) program’s image of the child is introduced and the impact of that image on the teacher’s role as well as the relationship between the teacher and the child. In Reggio Emilia programs, children are viewed as co-partners, not subordinates, in the inquiry process and are truly respected as competent learners. The author illustrates the different images of children in United States versus Reggio Emilia (Italy) by highlighting the type of tools/materials children have access to in Reggio Emilia programs and asking for students’ reactions regarding the different types of tools/materials. The immediate response is their outcry about concern for safety. The students feel materials/tools such as adult scissors and ladders are too dangerous to have in their own classrooms. When they are probed further to articulate what about these materials/tools are unsafe and why certain materials/tools are deemed “child” tools/materials vs. “adult” tools/materials, some students admit the real issue is sense of control for them. They, as classroom teachers, are expected to be in control of their own classrooms by themselves, children’s parents, and their supervisors. To the students, being in control of their classrooms means the teachers deciding what materials/tools will be available in the classroom, what and how subjects/topics will be covered, as well as when they will be covered and for how long during the year. Children are partners in learning so long as they do what the teachers set out for them to do; otherwise, teachers were deemed as not having complete control of the classroom.

The type of relationship a teacher has with children, according to the students, is one where the teacher has the expertise as well as the responsibility of making sure children learn what they needed to learn in a “safe” environment. The teacher-child relationship students are comfortable with is a top-down teacher-child relationship model where the teacher makes decisions concerning instruction and learning that will occur within the classroom but where children are “actively” inquiring about something within reason. The restriction associated with having children engage in an inquiry process is that the inquiry is only within the context of what the teacher determined as appropriate or “safe” for children of a certain age group and when directly supervised by the teacher (usually one-on-one or in a small group format where one child does what the teacher says while the rest of the group watches). The inquiry or research process for children, then, becomes more of an observing and listening process rather than one centered on active participation. Forman and Fyfe (1998) state, “knowledge is never verifiable through listening or by observation alone, but rather it gains clarity through a negotiated analysis of the communication process itself” (p. 239). This aspect of negotiated learning can only occur if the environment allows for total engagement, or if the teacher allows this opportunity by giving up control and truly listening to children. The sharing or collaboration means the teacher has to give up being the focus and let the children (i.e., learners) become the focus. The discussion of Reggio Emilia program principles (Wurm, 2005) (especially the image of the child) forces students to examine their own teaching beliefs, personal values, and teacher-child relationships. Therefore, it is essential to revisit principles of constructivist education such as (a) providing authentic and meaningful experiences, (b) active engagement of the learner, as well as (c) focusing on the learner, not the teacher.

Applying Constructivism

Even though the principles of the Reggio Emilia program are useful in helping with the understanding of constructivism, it does not lend itself to facilitating implementation of constructivist pedagogy because it is so foreign to university students. The students can resort to the excuse, “I can’t do that. It is a program from another country.” To facilitate application of constructivist pedagogy, students are required to implement the Project Approach (Helm & Kate, 2001), a program created by two North Americans, with children or with each other. The Project Approach emphasizes giving children more initiative, decision-making power, and ownership of their own learning than common early childhood teaching methods like units or weekly themes. Lillian Katz (1994), one of the designers of the Project Approach, provides the following explanation:

A project is an in-depth investigation of a topic worth learning more about. The investigation is usually undertaken by a small group of children within a class, sometimes by a whole class, and occasionally by an individual child. The key feature of a project is that it is a research effort deliberately focused on finding answers to questions about a topic posed either by the children, the teacher, or the teacher working with the children (p. 1).

The Project Approach also provides a layout of the process in three phases, which provides more structure to students in their attempt to implement constructivist pedagogy. This structure makes the implementation less scary. It can become a crutch for some students, resulting in various degrees of sharing control with the children in the inquiry process. The difference in the collaboration level with children or the learners is illustrated in the examples of group projects in the next section.

Examples of Group Projects Implemented by Students

Topic – Ocean Exploration

Phase I - Day 1 - Our project started by accident. I was visiting my mother [who] had a house full of children [age range one- to five-years] engrossed in an episode of “Sponge Bob Square Pants”. I was amazed by their reaction to the cartoon: All were watching. During the commercials, there were a few conversations, even a temper tantrum, but all was quiet when it came back on. When the cartoon was over, I asked them to name the characters. They eagerly went through the list. By the time we got through the entire list, it was time for them to leave. I asked if they would like to do a project about Sponge Bob and maybe visit the aquarium. They said, “Yes,” so we planned to meet the next day.

Day 2 - The next day I was unsure about the procedure so I began by asking some easy questions. My first question was, “Do “sponges” really live in the sea?” They sort of smiled then said “no”. I knew that there were sea sponges but I didn’t think that they knew that. The next question was from the theme song, “Who lives in a pineapple under the sea?” I asked if pineapples really grew in the sea, again smiles and a strong “no” followed. I asked, “What kind of homes are in the sea?” Children replied, “Shells.” I knew that two of the children had visited the ocean on vacation so we looked at pictures from the vacation and discussed some of the things to do and to see when one visits the ocean. They remembered the waves and looking for shells. They remembered that the sand was good for making sandcastles. They thought that the sea and the ocean were different things, so we talked about the location of the ocean. They knew it was in Florida and South Carolina, but they did not understand the magnitude of the ocean.

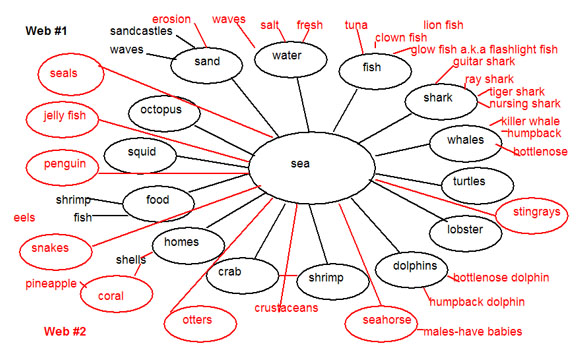

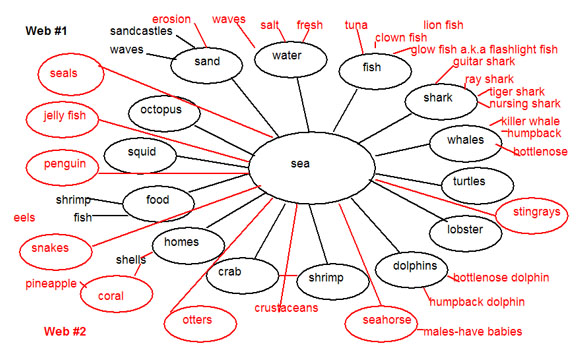

Phase II, Day 3 - I met with the group again on Monday to create a map of what they knew about the ocean (See Appendix 1 Web #1). We also wrote down our questions so that we could look up the information or ask questions when we went to the aquarium.

Day 4 - On Friday, we met again to plan our trip to the aquarium. We decided to go out to eat so I suggested going to a restaurant so that the children could taste some of the items that they said lived in the ocean. I gathered a plate that consisted of crab legs, scallop, lobster, shrimp, white fish, and oysters. We talked about the food chain of small crustaceans that eat plankton, and then larger fish eat them. And then we eat them. B. said, “Then the sharks eat us!” I had to laugh at this but they did just watch a rerun of “Jaws,” so I’m sure they think all sharks are man-eaters. We then decided to meet on Sunday after church to head to the aquarium.

Day 5 - We had a total of seven children and six adults. Our trip required two vehicles. I had brought along a collection of books that I had acquired about the ocean. When we were getting close, the children got excited because the signs had sharks on them. Before we went inside, I explained that they needed to pay close attention so that they could draw pictures of things they saw.

When we were near the end of the tour, we sat in the penguin area so the children could draw some of the things that they had seen. They scrolled through the pictures on the digital camera to see something that they needed to see again before drawing. They also enjoyed watching the penguins and began doing the “penguin walk,”

Day 6 - We planned to meet again the next day; but since I knew many of the children were unavailable, I sent home poster boards with them. I met with S., B. and J. They worked on making posters of some of the items that they saw at the aquarium. While they worked, they were able to go back to their sketches and the actual pictures from the aquarium.

Day 7 - We had a large pile of sand and a pool along with lawn chairs, sunglasses, and beach toys. I had buried shells in the sand before the children arrived so they could go out to look for shells. They counted the shells to see who found the most. They sorted the shells according to size, shape, and color. With the collection of beach items such as shells, starfish, seahorse, fish, and crabs, the children were asked to determine which would be the best place for the item to live, water or the sand. They easily put the fish in the water, but there were some items that they had seen in both places. We discussed how we might like to visit the ocean but it would not be a good home for us. After the sorting, children played for a while, making sand castles. We then decided to make wave bottles (plastic bottles filled with colored water and oil).

Phase III, Day 8 - I was now down to one child, S. When we were talking about a building project, I thought he would want to do a large paper mache replica of a whale like what we saw when we first entered the aquarium. I looked for a large box to start the process, and when I lifted the wardrobe box out of the closet, he immediately said, “Hey, this can be where they take up the money.” I wasn’t sure what he was talking about so I asked him to explain. He explained how at the aquarium the tickets were bought at a booth with a small opening for the money, credit cards and tickets to pass through. We decided to use the posters that they had been working on to be our exhibits and then create a ticket booth to sell the tickets for the aquarium. S designed, assembled, and painted the box with me cutting the box. We then went to the store to get items to create the aquarium. We found some stuffed animals in the shapes of fish (clown fish), lobster, and hammer head sharks for our gift shop - S. had already decided that we had to have a gift shop since it was how you exit the building at the aquarium.

Day 9 – S. continued his work on the ticket booth by constructing a cash register for the booth since our toy one was going to be used in the gift shop. S. also decided we needed a large picture of a shark for the wall when looking back on the pictures for ideas. He drew the shark and painted it.

Day 10 - I set up the program that spelled out the words as S. typed them in so he could make tickets. We also made signs (S’s interpretation) to tell what was in each “tank”. For example, with the picture of a group of fish he said, “Here is the teacher fish, and here are the kid fishes.”

Day 11- We picked up four more helpers today. G. worked on gathering items for the gift shop and an exploration station - a place with coral, shells, sand dollars, and starfish to be examined closely. G. made the signs for the gift shop and exploration station as well as set up the display area. B. worked on posters and helped with the gift shop. S. gathered the money and tickets to set up the ticket booth.

Day 12 - The area is set up, the exhibits are complete and workers are hired for the ticket booth and the gift shop. Family members came and bought tickets at the top of the stairs then proceeded down the hallway through the exhibits. The final room was the gift shop. They bought items, read books, and visited the exploration station. The parents were surprised at the extent of the project and were impressed with the participation of the children.

Reflection/Evaluation – Overall, I enjoyed working with the children. I feel guilty that it did not turn out as I had planned. I thought I would have more access to the children than I actually did. If I were to do a project like this again, I would definitely use children near my home. Another change I would make would be to document everything and not let anyone else touch the camera. I lost a few days of pictures when someone wanted to delete one picture. I would also make sure that many of the group members could be major contributors. I enjoyed trying the project approach, but I’m not sure that it is something I could use in the classroom. With 30-35 students in a cramped classroom, it would be difficult to mange. However with my family, it will be used often.

Topic - Ballroom Dancing

Phase I - Casual conversation in class is what sparked interest in our topic. As we were dismissed from class one night, we both mentioned getting home to watch a television show “So you think you can dance?” We briefly talked about the show, how we both loved it and thought the dances were neat. The following day, we discussed and recapped what happened on the show the previous night.

As we began project discussion later that night in class, we found ourselves with the dilemma of not having access to children. Together we decided we would focus on an adult approach together. Again, we discussed what happened on the show, but still had no idea on a project topic. C. mentioned the possibility of researching Ballroom Dancing, since we were both interested in the show and dances. Immediately we both agreed this would be a wonderful topic.

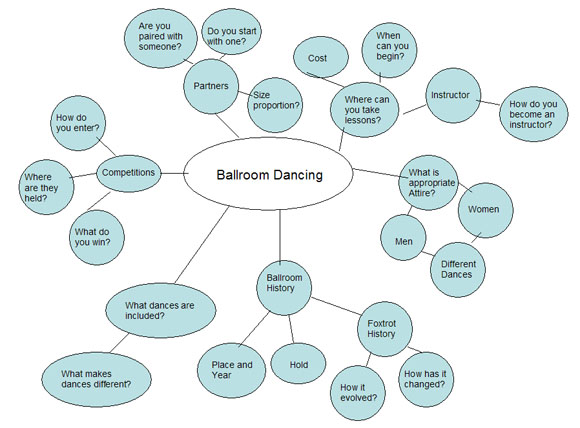

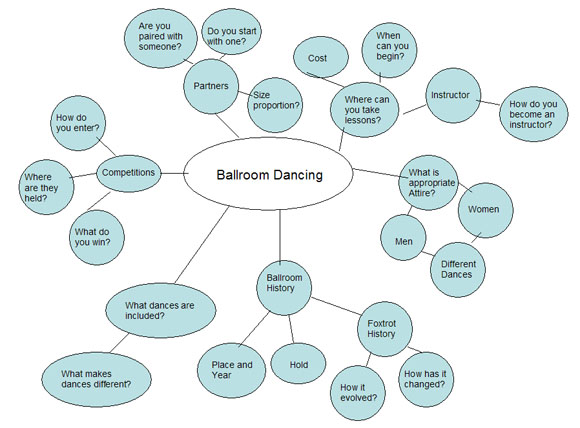

The next day, after watching the show, we were both full of questions. We both were curious about the dances included in ballroom dance, the history of ballroom dance, what appropriate attire included, questions about the instructor, where to take lessons, information pertaining to partners, as well as competition information (See Appendix 1 for webbing).

Phase II - We immediately began research to find answers to our questions. We met in the library to begin finding answers to our questions through Internet research. As we found information, we also developed more questions, along with a greater interest. We took our Phase I webbing of questions and divided the questions evenly amongst us. We each began separate Internet research to gather answers to our Phase I webbing of questions.

Through the internet research, we were able to answer questions on the history of ballroom dances, which dances are included in ballroom, information pertaining to timing of each dance, the beats per minute, and the basic step of each dance. We found partial information relating to appropriate ballroom dance attire for both men and women in both the European and Latin styles. Also from Internet research, we found the definition of ballroom dancing competition, along with the skill levels included for competition.

Though we found a lot of information through research and readings, we weren’t able to find everything we wanted. We both thought it would be a good idea to find a local studio offering ballroom dancing to observe and to possibly interview an instructor to help answer our questions. This would both answer our questions and give us a chance to see the actual dances.

C. was able to win two free dance lessons, which was wonderful for our project. This was a great opportunity and provided more information than we could find through basic research. With the free lesson, one receives a thirty-minute one-on-one lesson with an instructor, which provides an overview of the basics of ballroom dances. During the lesson, the first dance that was taught was the basic step of the Foxtrot, along with how to change direction within this dance. This dance is taught first because it is the most popular social dance and is known to be the easiest to pick up. This also became the dance that received more of our focus when researching the history. This was a great experience and lots of fun, which peeked our interest even more in ballroom dancing.

To help continue our research, we interviewed an instructor. Through the interview, we found answers pertaining to attire, dance classes, the role of the instructor, dance partners, and the competitions.

Phase III - For our culminating project, we had the opportunity to present our research and learning experiences to our peers. We organized our information and prepared for the presentation part of our project by revisiting the information we had gathered and began listing the answers to our webbing questions. Together, we organized our thoughts and chose the information that each person was going to present. We decided which dances were going to be demonstrated and which dance the class would participate. We gathered pictures from our lesson that we would show during the presentation, along with a few pictures found through research.

In class, we volunteered to present our project first because we were so excited about what we had learned and our experiences with ballroom dancing. We began by presenting our webbing of questions. Next we started answering the questions, allowing time for any questions from the audience. We then demonstrated the “hold,” explaining its origination and significance to ballroom dance. Next, ballroom dancing was demonstrated to the class - the Foxtrot, Waltz, Rumba, and Swing. The class then participated by learning the basic step of the Foxtrot. We continued to answer our webbing of questions, wrapping up the presentation through the showing of pictures.

Reflection/Evaluation – We were both very pleased with the presentation and. through comments expressed by the classmates, felt they enjoyed the presentation as well. Both of us learned a great deal pertaining to ballroom dance. This project has intrigued our interest even more about this topic and sparked an interest in enrolling in ballroom dance lessons.

Analysis/Implications for Practice

As student examples illustrate, participants in both projects learned a tremendous amount of information (See Appendix 1 and 2). What is fascinating is that the difficulty with constructivism lies more with the constructivist pedagogy with children, not in accepting the constructivist learning theory principles. With the ballroom dancing project, which was implemented with adults (i.e., each other), all components of constructivist education discussed at the beginning of the paper were met. This group took complete ownership of their own learning and made the learning experience meaningful and authentic for them through a dance lesson and interview. They also challenged themselves intellectually as well in motor skills: “Both of us have learned a great deal pertaining to ballroom dance. This project has intrigued our interest even more about this topic and sparked an interest to possibly enroll in ballroom dance lessons.” Having the focus on the learner instead of the teacher was not an issue for this group because they were the learners as well as teachers. However the Ocean Exploration project, which was implemented with children, the students found letting go of the teacher role was much more difficult: “I feel guilty that it did not turn out as I had planned” and “Another change I would make would be to document everything and not let anyone else touch the camera. I lost a few days of pictures when someone wanted to delete one picture. I would also make sure that many of the group members could be major contributors.” The collaborative learning concept of sharing the control and becoming co-learners with the children was still difficult for students.

So why is there this difference? This difficulty could be because becoming the facilitators of children’s learning means fostering children’s ability to be in control and guide their own learning by becoming researchers/inquirers. This necessitates going against the accepted “norm” of teachers being in charge. Also teachers are judged (i.e., held accountable) for children’s learning, and giving or sharing the control with children means risking how their supervisors will judge the teachers. The accountability push makes “trusting” in children’s competence very difficult. Teachers feel better when they can document that they have covered the required content and performance standards. Having children guide the direction of the project and having access to tools for inquiry leaves grey areas when teachers think of what children have to know according to the school system. Adults still believe that teachers are supposed to “teach,” not negotiate learning within a context of a community of learners that respects and values contributions of all members in action as well as words. Also, allowing inter- and intra-relationships to occur in classrooms among and between all members takes away the “management” control from the teacher. Supervisors, who are the evaluators of teachers, can view these learner-focused, actively engaged learners as chaotic and judge that the teacher has lost control of his/her classroom.

Therefore the key to having the students practice constructivist pedagogy in the field of early childhood education may be to have them experience constructivist education personally, with each other. Thus they become believers of the constructivist education pedagogy and see evidence of and believe in children’s competence. Additionally, the accountability concern has to be tackled in the course. One suggestion is to have the students document the early childhood content and performance standards covered with the projects implemented with children. When Dangel and Guyton (2003) reviewed 35 constructivist teacher education programs, they identified eight common elements of constructivist education across these 35 teacher education programs. These elements were: 1) reflection, 2) learner-centered instruction, 3) collaborative learning, 4) posing relevant problems/problem solving, 5) cohort groups, 6) extensive field placements, 7) authentic assessment/professional portfolios, and 8) action research or an inquiry approach to teaching. The author believes that implementing these eight elements, with emphasis on the fifth and seventh elements, is critical for future teachers to not only understand the instructional implications of constructivist theory but to practice constructivist pedagogy.

References

Barab, S., & Duffy, T. (2000). From practice fields to community practice. In D. Jonassen & S.M. Land (Eds.). Theoretical Foundations of Learning Environments. Mahwah, N.J: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Baxter Magolda, M.S. (2004). Evolution of a constructivist conceptualization of epistemological reflection. Educational Psychologist, 39(1), 31-42.

Brooks, M.G., & Brooks, J.G. (1999). The courage to be constructivist. Educational Leadership, 57(3), 18-24.

Chen, P., Chung, D., Crane, A., Hlavach, L., Pierce J., & Viall, E. (2001). Pedagogy under construction: Learning to teach collaboratively. Journalism and Mass Communication Educator, 25-42.

Dangel, J., & Guyton, E. (2003). Expanding our view of teaching and learning: Applying constructivist theory(s) to teacher education. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Association of Colleges for Teacher Educator in New Orleans, LA.

DeVries, R., Zan, B., Hildebrandt, C., Edmiaston, R., & Sales, C. (2002). Developing Constructivist Early Childhood Curriculum: Practical Principles and Activities. New York: Teachers College Press.

Duffy, T., & Cunningham, D. (1996). Constructivism: Implications for the design and delivery of instruction. In D. Jonassen (Ed.), Handbook of Research for Educational Communications and Technology (pp. 170-198). New York: MacMillan.

Forman, G., & Fyfe, B. (1998). Negotiated learning through design, documentation, and discourse. In C. Edwards, L. Gandini, & G. Forman (Eds.). The Hundred Languages of Children: The Reggio Emilia Approach-Advanced Reflections (pp. 239-260). Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Helm, J.H. & Katz, L. (2001). Young Investigators: The Project Approach in the Early Years. New York: Teacher’s College.

Hill, L., Stremmel, A., & Fu, V. (2005).Teaching as Inquiry: Rethinking Curriculum in Early Childhood Education. Boston, MA: Pearson Education.

Phillips, D.C. (2000). An opinionated account of the constructivist landscape. In D. Phillips (Ed.), Constructivism in Education: Opinions and Second Opinions on Controversial Issues (pp. 1-16). Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago.

Wurm, J. P. (2005). Working in the Regiision way: A beginner’s guide for American teachers. Washington, DC: NAEYC.

Appendix 1:

Ocean Exploration Webs:

Ballroom Dancing Web:

Appendix 2

Answers to webbing questions found through research and interview

What dances are included in ballroom dance? And what makes them different?

Ballroom European Background

- Waltz ¾ time, 84-90 beats a min. movement 123 strong accent on 1

- Tango 4/4 time, 128-132 beats, quick, quick, slow

- Foxtrot 4/4 time, 112-120 beats, slow, quick, quick

- Quickstep 4/4 time, 200-208 beats, slow, quick, quick (variation of the foxtrot)

Latin : Latin Background

- Cha cha 4/4 time, 128 beats, 2341 accent on the 1

- Samba 2/4 time, 100 beats, 1-n-2 1-n-2 accent down beat

- Rumba 4/4 time, 104 beats, 2341

- Salsa 4/4 time, 160-22- beats, quick, quick, slow

- Swing 4/4 time, 136-144 beats, 123456

History

-Ballroom from a place where a ball (formal/social dances) may be held

-Ball derives from the Latin “ballare” meaning “to dance”

-Hold derives from the 1500’s when men wore swords on their left

History of Foxtrot

Originated summer of 1914 by Actor Harry Fox. The Fox-trot originated in the Jardin de Danse on the roof of the New York Theatre. As a part of his act downstairs, Harry Fox was doing trotting steps to ragtime music, and people referred to his dance as “Fox’s Trot”.

The foxtrot was the most significant development in all of ballroom dancing. The combination of quick and slow steps permits more flexibility and gives much greater dancing pleasure than the one step and two step which is has replaced. There is more variety in the foxtrot than in any other dance, and in some ways it is the hardest dance to learn! Variations of the foxtrot include; the Peabody, the quickstep, and Roseland foxtrot. Even dances such as the lindy and the hustle are derived to some extent from the foxtrot.

What is considered appropriate attire?

Women: Ballroom gowns are long and flowing and can cost up to 4,000 dollars. Latin gowns are skimpy; Slick bottom dress shoe

Men: (Ballroom) Generally a tuxedo with a tie; Polished/Shined Shoes

(Latin) Black pants, Open collared button up shirt (No tie)

Where can you take lessons?

Specific names of dance studios in the vicinity areas

When can you begin?

You can begin anytime, with no experience

Instructor

You are assigned to one instructor, and they will be your instructor always

How to become an instructor?

Go through Ballroom teacher training. Each style consist of three week training and costs $2295 for each style (by style meaning ballroom and Latin) (Boston Area)

Cost

- Five 45min private lessons, unlimited group sessions (during duration of the five private lessons), and unlimited social parties - $399.00

- Nine 45 min private lessons, unlimited group sessions and unlimited social parties- 778.00

Partners

- Do you have to start with one? No. If you are a female, you will receive a male instructor. If you are male, you receive a female instructor

- Are you paired with someone? You will not be paired with another classmate

- Size proportion? Guy needs to be at least the same height of the female, should not be shorter. Need to look good together

Who takes initiative for starting lessons?

Usually women. A lot of women will come a few times alone, be showing male companion steps and what she has learned, then they will accompany.

Competitions?

Each school usually holds own competition.

- How do you enter? Enter through your school ( if it is held outside of your school)

- Where are they held? All over the world /Competitions are held all the time

- International Grand Ballroom Championship will be held in San Francisco

- What is a dance competition? Allows dancers to show and compare their skills with other dancers at a similar level.

- Competition consists of many events, each of which is targeted at a particular skill level. Each competitor is required to perform one or more dances from a given division. As competitors move up a skill level, they are required to perform additional dances in the respective category. Not all skill levels or divisions are offered at all competitions.

Dance Skill Levels

- Championship

- Pre-championship

- Novice

- Novice Syllabus (restricted step)

- Newcomer

- What do you win? Scholarships

Cheryl Mimbs-Johnson, University of Kentucky

Barbara A. Clauss, Indiana State University

Jacquelyn W. Jensen, Eastern Kentucky University

Maxine L. Rowley, Brigham Young University

Candace Fox

Mount Vernon Nazarene University

Jaesook L. Gilbert

Northern Kentucky University

Gale Smith

University of British Columbia

Dorothy I. Mitstifer, Kappa Omicron Nu

|