|

Kappa Omicron Nu

FORUM

The Role of Philosophy in Home Economics

Sue L. T. McGregor

Mount Saint Vincent University

2012

Keywords: home economics, practice, philosophy, belief system, mission, comparative philosophy

Introduction

This paper discusses the role of philosophy in home economics practice. What is it, why do we need one, what role does it serve, and what should it include? Following the lead of Dahnke and Dreher (2011), this paper reinforces their idea that a discipline focused on practice (as is home economics) has a special responsibility to (a) rely upon a guiding philosophy, (b) socialize new members into that philosophy, and (c) educate the public about the discipline’s focus on praxis, informed by its philosophy. To begin, the paper will generically define each of profession, professional, practice, and philosophy, followed with a richer discussion of these concepts within the home economics context. Both the form and the substance of a philosophy are examined as well as their import on the best approach for home economics philosophy.

The 4Ps: Profession, Professional, Practice, and Philosophy

A profession provides a set of services that are beneficial to society as a whole (Brown & Paolucci, 1978). A professional is a person practicing within a profession, drawing upon general and specialized (expert) knowledge and guided by high standards of professional ethics (Kieren, Vaines & Badir, 1982). Practice is identifiable action inherent in a given profession (Dahnke & Dreher, 2011). All professionals should have a philosophy that stems from the profession as a whole and is aligned with the latter (Vaines & Wilson, 1986). A philosophy contains ideas about what is important in relation to quality and ethical practice; it is a particular system of beliefs, a set of rules for, and principles of, practice (MacFarland, Cartmel, & Nolan, 2010). A philosophy contributes to professionalism because it offers goals, values, and attitudes for which to strive. As well, a philosophy helps professionals be aware of what they are doing and why (Merriam, 1982). A philosophy is the means by which practitioners obtain, interpret, organize, and use information while making decisions and taking actions (Boggs, 1981). The main power of a philosophy is its ability to help practitioners better understand and appreciate what they do and why (Brockett, 1998).

Placing 4Ps in the Home Economics Context

Brown and Paolucci (1978) made a strong case for home economics holding the “honorific status of profession” (p. 6) along four criteria. First, as noted above, home economics provides a set of services beneficial to society as a whole. It focuses on the home for the good of humanity.

Second, the provision of these services involves rigorous, responsible intellectual activity, especially moral

judgments. As members of a profession, home economists continually engage in scholarly activity

focused on the critique of existing knowledge and on how it matches the evolving needs of individuals and families. The home economics profession faces the challenging reality that everyone lives in some form of home environment and familial arrangement. To offset the tendency for anyone thinking she or he can provide services for individuals and families, the profession strives to build its practice upon human ethics and moral concerns, not just upon technical how-to practice.

Third, home economics is a profession because its members seek to assure others that their work is morally defensible, both in its nature and it performance. To this end, practitioners engage in self reflection and self critique, so they can present themselves and the profession to the public in such a way that society is very clear about what we offer (Brown & Paolucci, 1978; Kieren et al., 1982). This transparency ensures that the profession asks the appropriate questions, poses the correct problems, and identifies the underlying causes of the symptoms with which individuals and families are trying to cope. The result is professional practice and ethical conduct.

Finally, because of the level of competence and independent, intellectual thought required to practice in any profession, the scope and purpose of the home economics profession is necessarily limited. However, the complexity of the knowledge and the attendant practice of home economics are not limited; it is profoundly complex and nuanced. Most significantly, although the field has generated specializations to reflect the scope of the profession’s mandate, all such areas of expertise, ideally, adhere to the same, agreed-to, philosophy (Brown & Paolucci, 1978; McGregor, 2011).

In particular, home economics practice occurs within a mission-oriented profession rather than discipline-oriented. Mission-oriented practice (also includes education, social work, and medicine) builds upon basic processes and applies these processes to provide services that benefit society as whole (e.g., a focus on the home for the good of humanity). Knowledge or knowing is for the sake of doing something with the knowledge in one’s practice. This is very different from a discipline-oriented field, which views knowledge as an end, or to know for the sake of knowing (Vaines, 1980).

Being a mission-oriented profession means practitioners focus on a mission and on valued ends. The full intent of home economics practice is to bring about a change in the person(s) being served by fostering changes in the system of concepts that a person uses when interpreting and acting upon the self and the environment. A related intent is to provide services with specific ends that are in the interests of larger society. Such ends are examined and judged by members of the profession in collaboration with those persons served; hence, they are called valued ends rather than predetermined or given by some expert (a given end). This is what is meant by being a mission-oriented (valued ends) profession; practitioners need knowledge to accomplish practice with moral overtones (Brown, 1980; McGregor & Gentzler, 2009).

Hand-in-hand with being a mission-oriented profession comes being problem-oriented rather than subject matter-centred. In particular, the problems best suited for home economics are perennial and practical in nature. Perennial means each generation of families faces similar problems, just in different contexts (e.g., the need for shelter, food, clothing, child care). Because we are mission-oriented and focused on valued ends, home economists deal with these enduring problems in socially responsible and morally defendable ways. A practical problem is concerned with thoughtful action in situations for which reflective decision-making is required, rather than rote or standardized approaches. What worked before may not be appropriate in the new context. Thus, home economics professionals are required to use judgment based upon an understanding of all the variables of each particular situation (Brown & Paolucci, 1978; Vaines, 1980).

It bears repeating that home economists must continue to critique the human condition, which means investigating and denouncing social and individual damages caused by power imbalances in society. Mission-oriented professionals strive for praxis; that is, home economists engage with real inequality in society and then seek to link the insights they gain from their ongoing critique to engage in social and political action (Brown & Paolucci, 1978; McGregor, 2010).

The Role of Philosophy

As explained above, practitioners within the home economics profession are held to the highest ethical and moral standards because their practice impacts the human condition, as shaped by daily life within families and the home. It behoves us to adopt a unifying philosophy of practice that establishes the individual, the family, and the home as the primary beneficiaries of the profession. Inculcation of profession-wide philosophies requires rational, practical, and inclusive approaches that engage all segments of the profession. Such a strategy contributes to unifying a profession in pursuit of its mission via a profession-wide dialogue (Maddux et al., 2000). Practitioners identify the challenges of trying to adopt a single professional philosophy and model of practice, challenging anyone engaged in a discussion of professional philosophies to remember it is not about what people do but why they do it. The why of professional practice in mission-oriented fields is informed by the philosophy.

Cipolle, Strand, and Morley (1998) explained that a philosophy of practice helps practitioners make decisions that lead to the formation of ethically consistent practice. This consistency can happen because a philosophy defines the rules, roles, relationships, and responsibilities (4Rs) for the practitioner that guide day-to-day and career-long professional practice. Without a professional philosophy, practitioners cannot really know what is motivating them to make such large decisions (with moral overtones). This situation is exacerbated when practitioners’ philosophical convictions are subconscious or not clearly articulated (Thomas, 2011; Vaines & Wilson, 1986).

Components of Home Economics Philosophy (Form and Substance)

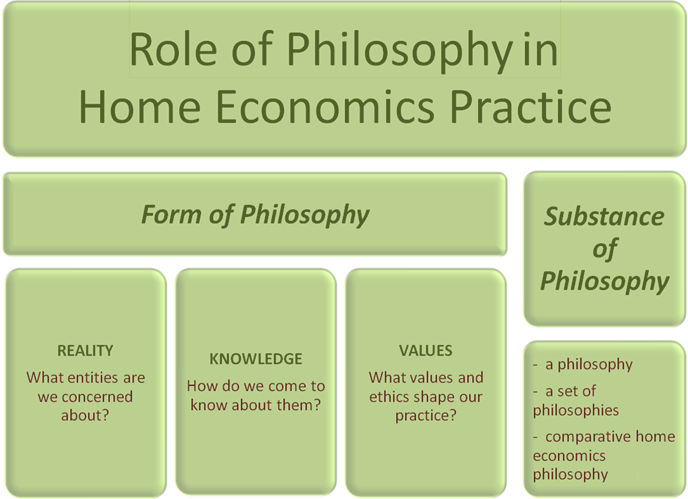

Salsberry (1994) suggested that a philosophy could have both form and substance (see Thomas, 2011). The form of a philosophy comprises three parts: reality (ontology), knowledge (epistemology), and values and ethics (axiology). Reality asks what entities exist within, are fundamental to, the domain of home economics? Knowledge asks by what claims (how) can the basic phenomenon of home economics be known? Ethics asks what does the domain of home economics value? Succinctly, a philosophy is “a set of beliefs about what the basic entities of [a discipline] are, how these entities are known, and what values should guide the discipline” (Salsberry, 1994, p. 18). The form of philosophy for home economics wants to know what entities are we concerned about, how do we come to know about them, and what values shape our practice (see Figure 1)?

Figure 1. Role of Philosophy in Home Economics Practice

A standard rhetoric exists worldwide about the raison d'être, the form, of home economics as a discipline and a profession. In short, individuals and families (alone and as social institutions) are our focus (reality). We come to know about them by studying their day-to-day lives lived out in their homes and households, shaped by internal and external factors (knowledge). The intent is to improve, optimize, and enhance their well-being and quality of life (values and valued ends).

The form of our philosophy is one thing; however, the substance of a guiding philosophy to function within that form is quite another (Salsberry, 1994). Although the form of a philosophy provides a framework for professional action (clarifies entities, how we know them, and through what value lens), the substantive dimension of a philosophy entails conceptual clarification and assessment of various arguments about reality, knowledge, and ethics (Edwards, 1997). Philosophy is supposed to inspect all areas of life and question each practice’s fundamental concepts and presumptions (Romano, 2009). The substance of the philosophy of any discipline (home economics included) entails the creation of a unique perspective on the discipline’s phenomena of interest (Salsberry). What constitutes the uniqueness of this perspective depends upon whether we think we need a philosophy of home economics, a set of home economics philosophies, or something else.

Three Approaches to Substance of Home Economics Philosophy

A philosophy gives meaning and boundaries to home economics practice. Nonetheless, most home economists have never taken a philosophy course. Romano (2009) noted that other disciplines face the same dilemma. Thomas (2011) asserted we do not all have to be philosophers, but we do need to know where we stand in the world, what we are expected to do as professional practitioners, and to what ethical and moral standards. Because the knowledge base of home economics practice is always changing to keep pace with the changing face of humanity, it is important to have a solid foundation from which to practice—a philosophy is that foundation and even that can change over time. One could say that a philosophy is a reflection of the profession’s personality, professional culture, beliefs, attitudes, and values—its mission. Without question, philosophies affect professional decisions and actions taken in practice (Bryan, 2006).

The title of this paper is the role of philosophy in home economics. For some time, I have been contemplating whether we should say ‘a philosophy of home economics’ or a set of ‘philosophies of home economics.’ This query is shared by both Drs. Kaija Turkki (Finland) and Donna Pendergast (Australia), fellow home economics philosophers. They both argue that philosophies of home economics (plural) is a term that respects the diversity of what constitutes home economics as it is practiced around the world (personal communication). Edwards (1997)

expressed similar concern for the nursing profession, pondering which is most

relevant: a philosophy of nursing or philosophies of nursing. If the latter, then “any one specific philosophy of nursing can only be an instance of the subject-area denoted by the expression ‘philosophy of nursing’” (p. 1090).

Perhaps the answer is a third approach, a comparative home economics philosophy. A comparative approach makes comparisons across various time frames, regions, or cultures as something develops. This approach would challenge the assumption that how home economics evolved in one country is the way it evolved around the world. Niehof (2011), from the Netherlands, explained that the profession of home economics was formalized during the Lake Placid conferences in North America (1899-1909), but it then evolved along different paths around the world as it grew in importance. As the profession expanded around the world, so did notions of what constitutes a philosophy of home economics practice. Indeed, home economists in different countries now hold different conceptualizations of what constitutes home economics (Whalen, Posti-Ahokas, & Collins 2009).

To illustrate further, following on the heels of the very influential American monograph about how to define home economics philosophy (Brown & Paolucci, 1978), Brown, a renowned American home economics philosopher, wrote three tomes about home economics philosophy in United States, especially volume three (Brown, 1993). But, the North American notion of what counts as home economics philosophy is not used worldwide. In my epilogue for a book on home economics practice in Scandinavia (Tuomi–Gröhn, 2008), I noted that (a) North American home economists draw on Habermas (German philosopher), (b) European and Scandinavian home economists draw on Merleau-Ponty, Husserl, and Heidegger (German and French), (c) and Japanese home economists draw on Bollnow (German). Given this wide range of philosophical inspirations, it stands to reason that what is considered a philosophical framework for home economics practice would differ around the world. This diversity became self-evident in a profile of different vignettes of home economics philosophies in five regions of the world (McGregor, 2009) (see Table 1, which identifies examples of both form and substance).

Table 1. Evidence of diversity of opinions about what counts as home economics philosophy, from five different global regions (McGregor, 2009)

- Embrace new notions of what it means to be an expert (expert Novice and integral specialist) (substance);

- consider the idea of having fun and taking pleasure while

practicing on the margins, and of resisting normalization (carnival and carnivalesque) (substance);

- move far beyond interdisciplinary to the energizing spaces of transdisciplinarity transformation and integral thinking (substance);

- embrace celebratory, reflective leadership with a focus on human action (ethical, spiritual and authentic) and human as well as intellectual capital, rather than conventional management and transactional leadership (form and substance);

- choose to focus on the human condition, basic human needs and qualities of living rather than well-being and quality of life (form);

- use new conceptualizations of the home (the house as a place for humanity and the ascendency of human beings rather than just shelter for individual families) (form);

- consider the concepts of wholesight and being-in-the-world (substance);

- conceive our body of knowledge as agent-centered rather than subject- or content -centered (facilitated through communities of practice instead of separate specializations) (substance);

- show a newfound respect for everyday life, especially how people make sense and meaning within their daily life (form);

- adopt different notions of what competent practice looks like (predicated on sustainability of culture and society, personal and social responsibility, and a willingness to live and manage together) (substance);

- accept the idea that everyone on earth has a right to basic education for life competence (a rights-based approach) so as to foster the culture of family life (form and substance);

- move away from integrated practice to integral practice (shift from balance and harmony to a respect for the emergent and healthy tensions that hold things together as they continually evolve in an attempt to see order emerging in chaos) (substance);

- position the profession beyond patriarchy (substance); and,

- consider the restoration of humanity by viewing home economics as a discipline for human protection focused on the soundness and fullness of human life and existential hope (based on the assumption that the destruction of private life leads to the destruction of the conditions of humans in general) (form and substance).

|

Discussion

“The broad overall goal of home economics is to provide benefits for mankind [sic] through the delivery of a wide range of human services” (Kieren et al., 1982, p. 118). We are making decisions about problems facing humanity that may not have solutions in our lifetime. For this reason, it is imperative that we have some sort of philosophical underpinnings to guide our practice. “Home economics is subject to a continuous process of change and redefinition” (Wahlen et al., 2009, p. 34). In the face of this change, we must continually examine and redefine our philosophical underpinnings.

The process of conversing about philosophy of home economics can be empowering because it provides an opportunity to reflect upon, and identify, what is meaningful within our professional practice (see Kinsella, 2001). We have to ask ourselves if we are still in agreement on the long-standing form of our philosophy reiterated here: Individuals and families (alone and as social institutions) (reality) are our focus. We come to know about them by studying their day-to-day lives lived out in their homes and households, shaped by internal and external factors (knowledge). The intent is to improve, optimize, and enhance their well-being and quality of life (valued ends). This form was supported by a particular substance of philosophy: interdisciplinarity; systems, eco, and human ecosystems thinking; a global perspective; social change theory; practical problem solving; moral values reasoning; and system of actions, all focused on the concepts of well-being and quality of life (McGregor, Pendergast, Seniuk, Eghan, & Engberg, 2008).

Do we want to redefine our focus, how we came to know about it, and from what value set? What would this reframing look like? We could shift our focus to a study of individuals and families and their art of everyday living and how this helps the home become the protector of humanity. We could shift our focus to the human family and study how the home performs as the arena that shapes the human condition. We could shift our focus to the family as a social institution and study how various societies respect this institution as the cornerstone of the future of humanity. Each of these scenarios, and others, represents a different form of philosophy than we have now: a different notion of reality (which entity is our focus), a different way of knowing about this reality, and from which set of values.

The substance of our philosophy would change profoundly if we shifted forms of philosophy (i.e., different reality, knowledge, and values). And, if the substance of our philosophical base changes, our ideologies, research methodologies/paradigms, theories, methods, results reporting, and applications to professional practice (pedagogy, policy, human service delivery) would all change as well (McGregor et al., 2008). A philosophy of practice is a changing and dynamic entity, reflecting changes in the profession, its practitioners, individuals and families, and the world at large. What appeared the right thing to do in years past may change as new understandings emerge and as the world becomes more complex (Kinsella, 2001).

Conclusions

Philosophy plays a profound role in our practice as a mission-oriented profession focused on practical, perennial problems that span generations. “A fully articulated professional philosophy of practice can serve as a grounding point [an anchor] from which to examine professional activities and actions” (Kinsella, 2001, p. 1). Are we still doing the right thing, given what humanity needs to survive and thrive, through the family and the home? This is always our anchor, our guiding question.

The time is right for a world-wide discussion about what would serve us best: a philosophy of home economics, philosophies of home economics, or comparative home economics philosophy. First, an agreed-to world-wide professional philosophy may “mean a more sustainable profession on a global scale, a deeper assurance of consistency in practice, a stronger ability to ride the currents of change, and a far-reaching sense of solidarity” (McGregor & MacCleave, 2007, p. 15). This would be a philosophy of home economics. Second, after holding an international dialogue about the issue, we might agree that each region will embrace a context-specific home economics philosophy. What works in North America as substantive philosophy may not be appropriate for Asia, Africa, Europe, Oceania and vice versa. Third, we may have an international dialogue and agree to adopt a comparative home economics philosophy that respects the global diversity of home economics practice, perhaps with an agreed-to form (see Figure 1) but with different substance, depending upon the context.

We are not isolated islands. We belong to the worldwide profession of home economics, with members practicing in almost 200 countries. Given this contextual professional mosaic, we can anticipate a philosophical mosaic as well. A true professional will choose to identify with the profession, but she or he also will need to draw strength from the philosophical identity and culture of the profession (McGregor, 2006; McGregor & Goldsmith, 2010). Given our moral responsibility to humanity, home economics must continue to (a) articulate a philosophy of practice, (b) engage in collective dialogue about this practice dynamic, and (c) work together to create practice that is consistent with the valued ends of the profession.

References

Boggs, D. L. (1981). Philosophies at issue. In B. W. Kreitlow (Ed.), Examining controversies in adult education (pp. 1-10). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Brockett, R. G. (Ed.). (1998). Ethical issues in adult education. NY: Columbia University Press.

Brown, M. M. (1980). What is home economics education? [Microfiche]. Minneapolis, MN: University Department of Vocational and Technical Education.

Brown, M. M. (1993). Philosophical studies of home economics in the United States: Basic ideas by which home economists understand themselves (Volume 3). East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University.

Brown, M., & Paolucci, B. (1978). Home economics: A definition. Washington, DC: AAFCS.

Bryan, C. (2006). Professional philosophy. Retrieved from University of Tennessee Martin website: http://www.utm.edu/departments/hhp/docs/Philosophy.doc

Cipolle, R. J., Strand, L. M., & Morley, P. C. (1998). A new professional practice. In R. Cipolle, L. Strand and P. Morley (Eds.), Pharmaceutical care practice (pp. 1-35). NY: McGraw-Hill.

Dahnke, D., & Dreher, H. (2011). Philosophy of science in nursing practice. New York: Springer.

Edwards, S. D. (1997). What is philosophy of nursing? Journal of Advanced Nursing, 25, 1089-1093.

Kieren, D., Vaines, E., & Badir, D. (1984). The home economist as a helping professional. Winnipeg, MB:Frye Publishing.

Kinsella, E. A. (2001). Examining your professional philosophy. Occupational Therapy Now, 3(3), 10-12.

MacFarland, K., Cartmel, J., & Nolan, A. (2010). Early Childhood Care and Education leadership modules - Module 3 Philosophy. Retrieved from the Early Childhood Care and Education website: http://www.ecceleadership.org.au/node/14

Maddux, M., Dong, B., Miller, W., Nelson, K., Raebel, M., Raehl, C., & Smith, W. (2000). A vision of pharmacy's future roles, responsibilities, and manpower needs in the United States. Pharmacotherapy, 20(8), 991-1020.

McGregor, S. L. T. (2005). Professionalism in the new world order. Journal of Family and Consumer Sciences, 97(3), 12-14.

McGregor, S. L.T. (2006). Transformative practice. East Lansing, MI: Kappa Omicron Nu.

McGregor S. L. T. (2009). International conceptualizations of a 21st century vision of the profession. Kappa Omicron Nu FORUM, 18(1)/archives/forum/18-1/mcgregor.html

McGregor, S. L. T. (2010). Locating the human condition concept within home economics [Monograph #. 201002]. Retrieved from http://www.consultmcgregor.com/documents/publications/human-condition-monograph-2010.pdf

McGregor, S. L. T. (2011). Home economics as an integrated, holistic system: Revisiting Bubolz and Sontag’s 1988 human ecology approach. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 35(1), 26-34.

McGregor, S. L. T., & Gentzler, Y. (2009). Preserving integrity: University program changes. International Journal of Home Economics, 2(1), 15-29.

McGregor, S. L. T., & Goldsmith, E. (2010). Defogging the professional, philosophical mirror. International Journal of Home Economics, 3(2), 16-24.

McGregor, S. L. T., & MacCleave, A. (2007). Analysis to determine Canadian, American, and Australian agreement about home economics/family and consumer sciences professional competency domains. Kappa Omicron Nu FORUM, 17(2), /archives/forum/17-2/home_economics_professional_competency_domains.html

McGregor, S. L. T., Pendergast, D., Seniuk, E., Eghan, F., & Engberg, L. (2008). Choosing our future: Ideologies matter in the home economics profession. International Journal of Home Economics, 1(1), 48-68.

Merriam, S. B. (1982). Somethoughts on the relationship between theory and practice. New Directions for Continuing Education, 15, 87-91.

Niehof, A. (2011). Conceptualizing the household as an object of study. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 35, 488-497.

Romano, C. (2009, November 15). We need ‘Philosophy of Journalism’. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from http://chronicle.com/article/We-Need-Philosophy-of/49119

Salsberry, P. J. (1994). A philosophy of nursing. In J. Kikuchi and H. Simmons (Eds), Developing a philosophy of nursing (pp. 11-19). London: Sage.

Thomas, W. R. (2011). Why does anyone need a philosophy? Retrieved from the Atlas Society website: http://www.atlassociety.org/why_does_anyone_need_philosophy

Tuomi–Gröhn, T. (Ed.) (2008). Reinventing art of everyday making. Frankfurt, Germany: Peter Lang.

Vaines, E. (1980). Home economics: A definition. A summary of the Brown and Paolucci paper and some implications for home economics in Canada. Canadian Home Economics Journal, 30(2), 111-114.

Vaines, E., & Wilson, S. (1986). Professional action: Using the theoretic framework of practice. Canadian Home Economics Journal, 36(4), 153-157.

Wahlen, S., Posti-Ahokas, H., & Collins, E. (2009). Linking the loop: Voicing dimensions of home economics. International Journal of Home Economics, 2(2), 32-47.

Acknowledgement: An earlier version of this paper was presented as a Plenary Address at the 2012 Latvian 5th International Scientific Conference on Rural Environment. Education. Personality. (REEP).

Sue L. T. McGregor,

Mount Saint Vincent University

Vija Dišlere,

Latvia University of Agriculture

Sue L. T. McGregor,

Mount Saint Vincent University

Sue L. T. McGregor,

Mount Saint Vincent University

Sue L. T. McGregor,

Mount Saint Vincent University

Sue L. T. McGregor,

Mount Saint Vincent University

Aesthetic Experiences, Bodily Being, and Enfolded Everyday Life

Henna Heinilä

Sue L. T. McGregor,

Mount Saint Vincent University

Peng Chen PhD, Higher Vocational Education College, China Women's University

Peng Chen PhD, Higher Vocational Education College, China Women's University

Sue L. T. McGregor,

Mount Saint Vincent University

Dr. Mary Gale Smith

Sue L. T. McGregor,

Mount Saint Vincent University

|

![]()