|

Kappa Omicron Nu

FORUM

Existentialism and Home Economics

Sue L. T. McGregor

Mount Saint Vincent University

2015

Abstract

This paper broaches the idea of existentialism as a viable concept within our professional philosophy. The basic premise is that any home economist who encounters people dealing with their existence as humans could benefit by knowing more about existentialism as a strand of philosophy. The paper begins by briefly explaining the origins of existentialism, with an attempt to provide examples of existentialism in Western culture, so readers feel more comfortable with the concept. This is followed with an effort to define this elusive concept, continuing with highlights of the scant evidence of existentialism in home economics literature. The paper then turns to a generalized discussion of several overarching themes comprising existentialism: existence precedes essence, facticity, freedom, authenticity, and the Absurd (anxiety, despair (loss of hope), nothingness, and alienation). The paper ends with some rudimentary ideas about what home economics might look like in different areas of practice if informed by existentialism, and invites home economists to carry this philosophical conversation into our future.

Introduction

At times, home economists (family and consumer sciences (FCS), human ecology, human sciences) work with individuals and families who are pondering the meaning of their lives and their existence as humans; especially in times of strife, tragedy, crisis, or major life transition. Examples of existential situations include teens struggling with their emergent identities, the elderly grappling with their legacy, terminally ill patients wrangling with death, people suffering from depression, people experiencing a crisis of faith, promising athletes confronting a career-ending injury, or parents dealing with their children leaving home. Each of these major life challenges prompts or triggers thoughts about the meaning of life, perhaps because these situations are not considered to be normal in the everyday life of individuals and families. Such circumstances serve to jar people out of their habits, dumping them into a space where they are left with only questions and few easy answers; indeed, there are simply no easy answers to questions about human existence.

This paper broaches the idea of existentialism as a viable concept within our professional philosophy. The basic premise is that any home economist who encounters people dealing with their existence as humans could benefit by knowing more about existentialism as a strand of philosophy. They can use this information for themselves (to find out who they are as a person) and when working with individuals and families. Making sense of one’s existence is an important part of being human (Allan & Shearer, 2012), meaning it should be an important part of home economics philosophy. However, despite its prevalence during the mid-20th century, there is little evidence of existentialism in the home economics literature, except for thoughts tendered by Brown (1978, 1985) and Sekiguchi (2004)1, and a few other proxy initiatives (to be discussed shortly).

Many philosophers believe it is time to reappraise the legacy of existentialism as an important dimension of contemporary philosophy (Burnham & Papandreopoulos, ca. 2012; Crowell, 2010). The same sentiment informs this paper about existentialism and home economics philosophy.

Origins of Existentialism

Existentialism flourished in Western culture and art during the 1940s-1970s, originating as a philosophical (some say intellectual) movement in Europe in the late 1800s, gaining popularity following World War II. Readers may recognize the names of some prominent existential thinkers: Kierkengaard, Sartre, Camus, Jaspers, Marcel, Merleau-Ponty, Heidegger, Nietzsche, Beauvoir, and Arendt (Crowell, 2010).

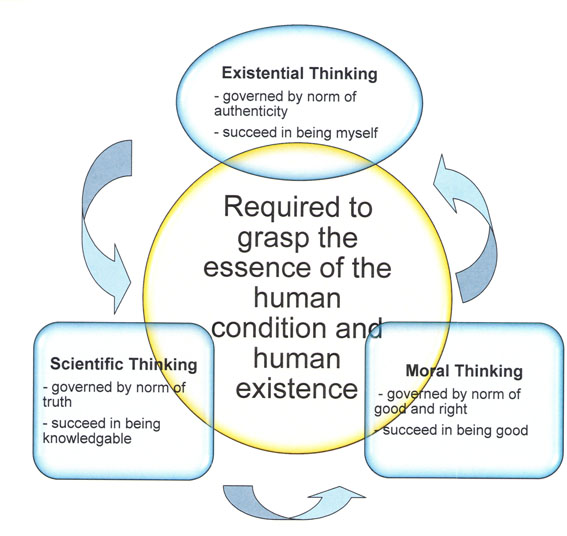

Crowell (2010) explained that the founders of existentialism believed that, in order to grasp the essence of the human condition and human existence, three modes of thinking are needed: scientific thinking, moral thinking, and existential thinking. Respectively, scientific thinking draws on “the basic categories of matter, causality, force, function, organism, development, motivation and so on” (p. 2). Moral thinking turns to the categories of “intention, blame, responsibility, character, duty, virtue, and the like” (p.2). Existential thinking holds to a further set of categories: “dread, boredom, alienation, the absurd, freedom, commitment, nothingness, and so on” (p.2). Science is governed by the norm of truth, morality by the norm of good and right, and existentialism by the norm of authenticity. The human condition cannot be fully understood unless people can be seen, respectively, as successful in being knowledgeable, successful in being good, and successful in being themselves. Regarding the latter, existentialism assumes that everyone is responsible for what they make of themselves. They alone determine their existence and what it means for them; no one else can do this for them (Crowell, 2010) (see Figure 1).

FIGURE 1 - Thinking required to grasp the essence of human existence

Western Examples of Existentialism

Existentialism is hard enough to say (pronounced eg-zi-sten-shuh-liz-uh m), let alone understand. “The term is very difficult, if not totally impossible to define” (Corbett, 1985, p.1). Perhaps familiarity with some popular movies can ease us into this philosophical discussion. It helps to know that well-known Western art was influenced by existentialism. Examples include Alice in Wonderland, the Monty Python movie The Meaning of Life, Stanley Kubrick’s movie 2001: A Space Odyssey, and the movie The Matrix. Other existentialist-inspired movies include the Fight Club, Ordinary People, A Clockwork Orange, Blade Runner, and The Shawshank Redemption.

The work of actor/director Woody Allen provides a telling example. Crowell (2010) explained that existentialism became a cliché in the 1970s in Woody Allen’s books and films. Cohen (2007) concurred, noting that “more than any other American writer, Mr. Allen put existential dread on the map” (p. 1). Woody Allen’s “existentialist intellectual sensibility” was formed by exposure to Paul Sartre and Albert Camus, who “argued that life has no God-given purpose, and that only man’s [sic] choices and struggles give it meaning” (Cohen, 2007, p.1). Cohen provided this example of Woody Allen’s version of the existential struggle, based on the American vaudeville and comedy act, the Three Stooges: “Moe smashes crockery ‘with pent-up fury that masked years of angst over the empty absurdity of man’s fate,’ while Curley weeps: ‘We are at least free to choose. Condemned to death but free to choose’” (p. 2).

Existentialism Defined

There is no general agreement on the definition of existentialism (Crowell, 2010). An etymology dictionary explains that “existential” is from Late Latin existentialis/ exsistentialis, pertaining to existence. Existent stems from ex "forth" and sistere "cause to stand"; that is, to bring forth into being - to exist (Harper, 2014). And, what is crucial is that the focus of existentialism is on human existence (Burnham & Papandreopoulos, ca. 2012).

People grappling with their human existence are facing existential issues. Wals (2010) described existential issues as real issues, meaning significant and serious rather than superficial and shallow. Behar (2012) explained that existential issues have to do with the plight of human existence, with the meaning of life, and with what meaning, if any, people’s lives have. To deal with issues pertaining to existing as humans, people ask specific questions, including 'With the limited time I have, what is really important? What do I value? What gives me joy and why does it give me meaning? What legacy do I want to leave for other generations and how can I accomplish this legacy? What is the best part of my life and why does it give me meaning?' (Behar, 2012).

From an existential perspective, life has no meaning until people figure out who they are (define themselves), what is true for them, and what their existence means in the larger scheme of things. People are literally on a quest for the meaning of life. They are keen to know themselves and their place in society. Existential issues reflect people’s ultimate concern for aspirations beyond the self, beyond the superficial (Wals, 2010). These issues pertain to how each person is related to the cosmos, and to a concern for the human condition (Allan & Shearer, 2012; Gardner, 1999). These concerns matter, because existentialism “sees a universe without intrinsic meaning, in which individuals must struggle to create meaning for themselves” (Rohmann, 1999, p. 7). This struggle endures because human existence is seen to be essentially incoherent, incomprehensible, and meaningless (Rohmann, 1999).

Furthermore, existentialism holds that people have no place to run (Sekiguchi, 2004) because, when born, “they are committed to an existence which they have not asked for and from which they cannot escape” (Brown, 1985, p. 807). Existentialists also hold that because of being trapped in this position, people tend to especially experience existential angst when facing extreme life situations. In these sometimes life and death scenarios, people may contemplate life’s meaning, and whether their own life has been meaningful. They try to come to terms with their existence as a human being, meaning they are trying to understand, accept, and deal with difficult life situations.

Most readers are likely familiar with the term existential angst: the stress of dealing with life’s largest questions, with the unknown, and with the responsibility that comes with the freedoms we enjoy as humans. People ponder and worry over “Why am I here? What is my purpose in life? What am I supposed to be?” Sekiguchi (2004) explained that “existential anxiety arises from the awareness that we alone are responsible for creating our own existence” (p. xiv). To complicate matters, existentialism holds that people are obliged to find meaning in their existence, rather than in any externally imposed doctrine. People’s essential natures as human beings are developed through the choices they make in life; this uncertain existence creates anxiety, or existential dread, the fear of nothingness (Rohmann, 1999).

To make light of this anxiety, cartoonists create cartoons (see Figure 2, used with permission from http://www.sangrea.net/free-cartoons/philosophy-cartoons.html). But, existential angst is very real. People despair (lose hope) over their life situations. They dread dying and having to face the unknown and unknowable situations. They cringe at the thought of there being nothing to live for. They wallow in defeatism and are crippled by skepticism. Some recoil under the terror of the weight of life. This deep aspect of people’s reality can be a burden carried as we try to figure out who we are, or a joy we experience when we do. It is why home economists should engage with existentialism to assess its merits.

FIGURE 2 - An existential cartoon

Existentialism in the Home Economics Literature

Existentialism is not normally on the radar of most home economists working with individuals and families (McGregor, 2014), although home economists often experience existential angst when pondering the meaning and future of the profession. Regarding the former, we tend to be antitheoretical and antiphilosophical in our approach to practice (Brown, 1993; MacCleave, 1995). And, we tend to narrow our focus on well-being and basic human needs instead of the human condition and human existence (Brown, 1993; McGregor, 2010). Perhaps this explains why there is a dearth of literature around existentialism in home economics?

What of the few home economists who have broached the topic of existentialism and the profession? Nearly 35 years ago, in her explanation of what constitutes a practical, perennial problem, Brown (1978) drew on existentialism to explain that human existence is totally dependent on conscious human choice. Her point was that if home economists hope to help individuals and families confront moral problems concerning “what to do” (p. 15), we have to become familiar with existentialism.

Indeed, a few years later, while recounting the profession’s evolution in North America, Brown (1985) identified existentialism as one of five movements of intellectual thought that could have an effect on home economics (the others being logical empiricism, dialectic, hermeneutics, and critical theory). She clarified that “existentialism did not flourish in societies in which empiricism had a long history of acceptance... . Most logical empiricists have rejected existentialism altogether on the grounds that it is not scientific” (1985, p. 811). It should come as no surprise that home economics failed to actively engage with existentialism in its philosophy, because home economics is deeply empirical in its nature (Brown, 1993).

Sekiguchi (2004) and her colleagues drew heavily on existentialism when they crafted a home economics philosophy for Japanese practitioners. First published in Japanese in 1977, this book was made available in English at the 2004 International Federation for Home Economics (IFHE) congress in Japan. This philosophy evolved over a 10-year period, culminating in a powerful testament to the merits of existentialism for the profession:

[E]xistentialism has the potential to be the starting point for home economics. ... [I]nsofar as it brings human existence into relief, existential thought is one critical theoretical basis for home economics. ... [U]tilizing existential thought as a tool [can] place contemporary humanity before our eyes. [Therefore], we cannot overlook as our foundation the existential point of view. (Sekiguchi, 2004, pp. 1-2)

Sekiguchi believed that “human beings are oriented toward a purpose in life” (2004, p. 52), which behooves home economists to help them on this journey. Existentialism “can provide an authoritative basis for home economics” (p. 52).

Vincenti (2009), an American home economist, tendered a rich overview of Sekiguchi’s (2004) book. Vincenti defined existentialism as focused “on interpreting human existence in the world as individual and unique for each person. Meaning [of life] is a choice” (2009, p. 61). She described home economics as “a science of human life and existence [that] seeks no less than social reconstruction to improve the human condition” (2009, p. 59). Both McGregor (2005), who also reviewed Sekiguchi’s book, and Vincenti observed remarkable complementarities with Brown and Paolucci’s (1979) philosophy of home economics. In particular, existentialism helps the profession “balance the individual human experience that emanates from the heart with that which comes from the intellect” (Vincenti, 2009, p. 60), see Figure 1.

There was passing reference to existentialism in the recent European book on home economics, titled Reinventing Art of Everyday Making (Tuomi-Gröhn, 2008), if only to say the topic would not be discussed in any detail: “we are not going into details about existential phenomenological philosophy [as we] clarify the teaching and learning skills of home economics and crafts” (Tuomi-Gröhn, 2008, p. 147). This statement signifies that they were fully aware of existentialism, but opted to not use it at that time. Appreciating that existentialism considers “the nature of the human condition as a key philosophical problem” (Burnham & Papandreopoulos, ca. 2012, p.1), McGregor (2010) developed an argument for the profession to engage with the concept of the human condition.

As a side note, Vaines (1994, 1998) gave a philosophical nod to existentialism when she included the unknown and the unknowable in her spheres of influence framework for home economics. This framework assumes that there are eight spheres of influence on individuals’ and families’ lives (domains of reality), regardless of where they live, the stage of life cycle, or generation. Conceptualized as a geodome, these spheres comprise the cosmos; the biosphere; the power sphere (politics and business); the public sphere (community and neighbourhood); the private sphere (home as factory, interrelationships and moral centre); the inner sphere (self); and, the unknown and the unknowable. The latter two accommodate things people do not yet know and will never know (the mysteries of life). These spheres can lead some people to existential dread and angst because of their inherent uncertainty and ambiguity.

Collectively, these home economics scholars vouched for the significance of existentialism in home economics philosophy and practice. They recognized it as an important intellectual movement that has the potential to provide an authoritative basis for the profession as it strives to interpret human existence and the human condition. Their respective critiques of the world and the profession back up their individual assertions of the powerful role of existentialism in home economics.

Encouraged by their convictions, this paper now provides an overview of existentialism. As a caveat, the intent of this paper is to explain the basic tenets of existentialism so others have a conceptual platform from which to consider how it can be applied to home economics. The paper intentionally remains at a generalist level, and provides a detailed overview of the fundamental dimensions of existentialism, considered to be a new and necessary contribution to the profession. While this approach could be criticized for being decontextualized from the field, the author felt it was important that home economics practitioners understand what existentialism is before they apply it in their context. This general level of understanding paves the way for carrying the conversation further through informed dialogue and critical considerations of existentialism in home economics practice. This work will entail deeper considerations of the import of existentialism in home economics philosophy, involving unpacking its meaning for our work and identifying avenues for progressing our philosophical work.

Five Overarching Existential Themes

Burnham and Papandreopoulos (ca. 2012) and Crowell (2010) tendered detailed accounts of many existential thinkers, and the latter’s diverse interpretations of what has been called existentialism. Indeed, although many of them refused to be called existentialists, they are still widely recognized as such. Instead of describing in detail how each of these thinkers differed on their take on existentialism, this paper will focus on key themes of existentialism, thought to “provide some sense of overall unity” (Burnham & Papandreopoulos, ca. 2012, p. 2).

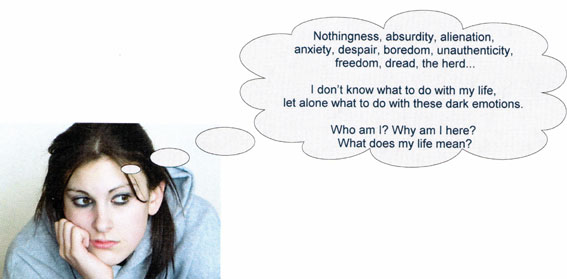

Brown (1985) explained that, although there are many different writers claiming to be existentialists holding greatly different doctrines, there are recurrent themes that appear in existentialist writings. Sekiguchi (2004) concurred, noting that the characteristics of the different schools are not as important as “how existential thought can provide an authoritative basis for home economics” (p. 52). In that spirit, five existential themes or concepts are explored in this section: existence precedes essence, facticity, freedom, authenticity, and the absurd (e.g., anxiety, despair (loss of hope), nothingness, and alienation) (see Figure 3).

Figure 3 - Major themes of existentialism

Existence Precedes Essence

Sartre coined the phrase existence precedes essence. This idea is central to existentialism, but very hard to grasp; nonetheless, this concept must be understood in order to appreciate other major themes (Crowell, 2010). Bottom line, in the beginning, a human being does not possess any inherent identity or value; people have no essence (i.e., no defining characteristic without which they would not be who they are). It is only through creating their own values, and determining the meaning of their own life, that people come to exist, and then gain essence (an intrinsic quality that determines their character); that is, existence comes before essence (Crowell, 2010), before a unique identity and self. Sartre believed that “We exist first; the self we subsequently become is a construct that is built and rebuilt out of experiences and behaviour. In principle, then, the self is something which can be changed, it can be reconstructed” (Stangroom & Garvey, 2005, p. 147).

Existentialism holds that self-creating people should come to their own understanding of what their life means instead of trying to meet a pre-established ideal of what humans should be like by relying on external dictates, doctrine, or customs. People are said to embark on “the fundamental project of the self,” and it is hard to choose a course of action that is out of character with this life project (Stangroom & Garvey, 2005). When we do choose out of character actions, we experience angst. To paraphrase Simone de Beauvoir (Sartre’s life partner), “one is not born a human, one becomes one.” Existentialism assumes that people’s existence consists of “forever bringing myself into being” (Burnham & Papandreopoulos, ca. 2012, p. 7); people are obliged to continually overtake themselves.

Facticity

Sartre made up the word facticity to accommodate his assumption that choices are not made in a vacuum; rather, people are expected to face up to the complex situations they confront—their facticity (Stangroom & Garvey, 2005). Burnham and Papandreopoulos (ca. 2012) referred to this as situatedness, wherein freedom always takes place in a particular context, defined by the facts at hand. Importantly, this distinction means people are not free to do anything at the drop of a hat; they are only free to act within the dictates of the context. From Sartre’s perspective, “facticity signifies all of the concrete details against the background of which human freedom exists and is limited. For example, these may include the time and place of birth, a language, an environment, an individual's previous choices, as well as the inevitable prospect of their death” (Wikipedia Encyclopedia, 2014c, p.1). Disregarding one’s facticity in the continual process of self-making and self-becoming could place one in self-denial, and create existential angst. Anyone in denial of their self could end up ascribing or projecting self-defeating meanings onto their life, exacerbating their angst.

As an example, consider two women, one of whom has no memory of her past and the other remembers everything. They are both married, but the first woman, knowing nothing about this, marries another man and leads a normal life (although she has in fact committed a crime). The second woman feels trapped in her existing marriage and secretly marries another man, thereby committing a crime, all the while blaming her past for trapping her in her present. The second woman’s facticity has changed, and she ascribes the meaning of being trapped to her past marital unhappiness. This scenario enters into her facticity as a choice she has made that contributed to defining who she is. This choice continues to define her to the point that she may feel she has lost herself. Facticity is both a limitation and a condition of existential freedom (Crowell, 2010; Wikipedia Encyclopedia, 2014a).

From a deeper philosophical stance, facticity has another meaning in existentialism. Fact means a thing that is indisputably the case. The suffix ity is Latin itatem, a condition or quality of being something (Harper, 2014). Facticity, therefore, refers to the state of being a fact. What does this have to do with existentialism? The term enables us to speak of person’s facticity—that she or he does, in fact, exist (no pun intended). However, and this is significant, one’s facticity cannot determine a person. Instead, “the fact that natural and social properties can be predicated of human beings is not sufficient to determine what it is for me to be a human being... because these properties are always in question. Who I am depends on what I make of my ‘properties’” (Crowell, 2010, p.7).

Freedom

Freedom and choice are central themes in existentialism. Sartre’s understanding of freedom is tied to human essence; that is, there is no essence at the beginning. Instead, people’s consciousness (a deep state of awareness) is detached from the world. It is empty and therein lies people’s freedom to imagine what might be the case in the future. Freedom is thus understood to be the “permanent possibility that things can be other than they are” (Stangroom & Garvey, 2005, p. 145 ). People have the freedom to become who they are in this “open future of possibilities” (p. 145).

With this existentialist understanding, it becomes obvious that existential freedom is not the same thing as freedom in the political sense; it is a psychological freedom. Hoffman (2009) explained that existential freedom cannot be separated from responsibility; freedom comes with responsibility. However, existentialists focus on the limits of the responsibility people bear as a result of this freedom (Crowell, 2010). There is always a psychological consequence if someone abuses their existential freedom, often expressed as guilt, dread, anxiety, depression, even anger at self, others, and the world. In an interesting twist, people are said to experience angst when they experience their own freedom, because nothing else is allowed to shoulder the responsibility (Hoffman, 2009).

Experiencing one’s own freedom is complicated, because people’s decisions and choices are not supposed to be influenced by societal or external norms; they are free to decide who they are and want to be/become, rather than have their identities dictated by external factors. Indeed, from an existentialist perspective, people are said to assume responsibility for their whole life, and they are in it for the long haul, for their whole life (Burnham & Papandreopoulos, ca. 2012). People’s ability to choose freedom is enhanced with self-awareness. “It can be frightening to deeply know who we are and the realities of our existence. Yet, it can be even more rewarding [than living a life being unaware of the realities of life]” (Hoffman, 2009, p. 2). Per The Matrix, the existential question is, do they take the blue pill (illusion) or the red pill (painful truth) (Hoffman, 2009)?

Freedom has an additional facet in existentialism. Not only are people responsible for themselves, to always strive to become, to exist and gain essence, they are also responsible for the consequences of their actions on others. Said another way, while people are responsible for their own choices as they create their own individuality, they are also responsible for all other persons. From an existentialist perspective, when people choose freely, they are charged with choosing responsibly for all humankind, in addition to choosing for their own existence (Brown, 1985).

Values also play a key role in existential freedom. Despite societal values, it is assumed that people are responsible for their own values, which can change. More compelling is the existential assertion that values are grounded in freedom. What people value makes a claim on them because values come with demands on the self (Crowell, 2010). For example, “I do not just see a homeless person but encounter him as ‘to be helped; ... I do not merely hear the alarm clock but am ‘summoned to get up’” (p. 14). In existentialism, values have exigency (pressing nature).

To illustrate, if I fail to get up when the alarm goes of, the alarm loses it exigency. But, if I fail to get up when the alarm goes off and it affects my job, my job gains exigency. If I value my job, would it have been irresponsible to not get up? How I answer that question reflects the kind of person I choose to be: respectable and accountable or laggard and lazy. When I become engaged with the alarm clock, and all that it means to me and who I am as a person, values appear. “Commitment—or ‘engagement’—is thus ultimately the basis for an authentically meaningful life” (Crowell, 2010, p. 15).

Authenticity

Existentialism holds that people are self-determining agents responsible for the authenticity of their choices. “Humans can choose to act authentically—intelligently and responsibly, wholeheartedly committing themselves to life and the development of their true being—or unauthentically, afraid of exercising their freedom and sinking instead into mundane conformity” (Rohmann, 1999, p. 128). When a person acts authentically, they choose something as their own, something apart from social sanction; they commit to themselves and succeed in being themselves. They come closer to being a human being “who can be responsible for who I am” (Crowell, 2010, p. 10). To be genuine (authentic) is to be free.

Not surprisingly, when acting with authenticity, people act with integrity; they can commit themselves to themselves rather than drifting in and out of life (acting unauthentically). Authentic people write their own life stories, instead of allowing their “my-story to be dictated by the world” (Crowell, 2010, p. 11). A person living authentically commits to “a certain way of being in the world [instead of] merely occupying a role” (p. 11). For example, being a better father is different from being concerned with what it means to be a father; the latter is existential authenticity.

Absurdity

Although discussed last, existentialism is predicated on the absurd, a concept developed by Camus. Absurdity refers to the futility of modern life. As an existential concept, it refers to a universe without intrinsic meaning, in which individuals must struggle to create meaning for themselves. If something is absurd, it is completely unreasonable, irrational, and out of tune with what would be expected. Absurdity describes pointless and illogical efforts to try to find meaning or purpose in an objective and uncaring world (Burnham & Papandreopoulos, ca. 2012; Rohmann, 1999). An example would be accumulating excessive wealth in the face of certain death. “Time erodes our achievements, death cuts short our plans” (Rohmann, 1999, p. 128). Existential absurdity presumes that “human existence as action is doomed to always destroy itself” (Burnham & Papandreopoulos, ca. 2012, p. 8).

Rohmann (1999) recounted the Greek myth of a man condemned eternally to push a heavy stone up a hill, only to see it roll back down again and have to begin the futile task ad nauseam; this is indeed absurd. For some people, this repeated action would seem defeatist while others may choose to learn who they are, and who they become, as a result of engaging with the absurdity of the situation. The former would experience existential angst; the latter would gain essence by examining their existence.

Crowell (2001) referenced “the absurdity of existence” (p. 12), and how it triggers anxiety, a sense of nothingness, and alienation (see also Burnham & Papandreopoulos, ca. 2012). Indeed, absurdism holds that

humanity must live in a world that is and will forever be hostile or indifferent towards them. The universe will never truly care for humanity the way we seem to want it to. [Hence,] it is easy to highlight the absurdity of the human quest for purpose [when] life’s absence of meaning seems to remove any reason for living. (“Absurdism,” 2014, p.1)

Existentialists believe that the answer to this angst, alienation, and sense of nothingness is to “learn to live with the absurd... [because] this lack of purpose [actually] presents humankind with true freedom” (“Absurdism,” 2014, p.1). Since the notion of the Absurd contains the idea that there is no meaning in the world beyond what meaning people can give it (Crowell, 2010), it seems imperative that people find a way to define their human existence.

Existentialism in Home Economics Practice

We now face the existential question, ‘what would existentialism look like in home economics practice’? A few examples of different areas of home economics practice might serve to bring this idea closer to home. First, in some instances, existentialism seems to validate current practice. To illustrate, consider that focusing on existential issues means people grapple with the way human beings and other species live together on the Earth (Jickling & Wals, 2012). Home economics has long focused on the morality, ethics, and sustainability of human choices and behaviour. Indeed, sustainability is a cross-cutting theme in the current American Association of Family and Consumer Sciences’ (AAFCS) Body of Knowledge (Nickols et al., 2009).

Burnham and Papandreopoulos (ca. 2012) described authenticity as “the existentialist spin on the Greek notion of ‘the good life’” (p.4), whereby people are “striving for existence” (p. 6). As a second example of validation, the existential perspective is reflected in home economics’ philosophical focus on “What is the good life? How do we define a good life?” (Brown, 1980; Smith, 1991). Greek thinkers (who informed Brown and Paolucci’s (1979) definition and mission of home economics) believed that the following issues are germane to any discussion of what is the good life: freedom from poverty, education and an examined life, freedom from fears, gods, honourable behaviour, friendship and security, and political and social obligations (Kahn, n.d.).

Third, what would an existential home economics pedagogy look like? The existential approach to home economics education would involve students seeking the meaning of life. This approach would be focused on emotions, thoughts, actions, and responsibilities as they relate to one’s purpose in life. Students would be taught they have freedom of choice, yet have to be responsible for the consequences (free exercise of moral decisions). The curriculum would place heavy emphasis on the humanities and fine arts, history and religious studies, presuming students would profit from the insights and judgements artfully expressed by others. An existential-informed home economics curricula would teach students to resist answers imposed from outside them; instead, students would strive for authenticity and for finding out who they are as a person, so humanity can progress (Marsh & Willis, 1999; McNeil, 1977; Wiles & Bondi, 2002).

Fourth, what about existentialism and politics? Existentialism does not dictate a specific political standpoint, but the stress on individuality and choice that this philosophy represents does have a political side. The principal concept is that freedom is the essence of being; to restrict people’s freedom is to rob them of that which makes them alive (“Existentialism and politics,” 2014). Home economists would appreciate that “the chief existential virtue—authenticity—would require a person to lucidly examine his or her social [and political] situation and accept personal culpability for the choices made in this situation” (Heter, ca. 2007, p.1). Those choices would become part of their facticity, shape who they are as humans, and influence life questions they would ponder, including politics.

Finally, home economics focuses on interventions as well as education, prevention, and development. What might a psychological intervention look like with an individual presenting with existential angst?

Existential therapy starts with the belief that although humans are essentially alone in the world, they long to be connected to others. People want to have meaning in one another's lives, but ultimately they must come to realize that they cannot depend on others for validation, and with that realization they finally acknowledge and understand that they are fundamentally alone (Yalom, 1980). The result of this revelation is anxiety in the knowledge that our validation must come from within and not from others. (Wikipedia Encyclopedia, 2014b, p. 4)

Home economists would have to grapple with the reality that many people feel they are ultimately alone in the world, even though the profession deeply believes in the family as the place of protection and stimulation for individuals (see Sekiguchi, 2004).

The End... The Beginning?

This paper began with the assertion that making sense of one’s existence is an important part of being human, meaning it should be an important part of home economics philosophy. The nuances of existentialism were teased out, based on the assumption that this information would be useful for other home economists who are intrigued with this idea. The paper suggested that it might be a viable concept for our consideration, a plausible avenue of exploration for its merit in our philosophical repertoire. A strong case was made for existentialism by our Japanese colleagues, who characterized it as “an authoritative basis for home economics” (Sekiguchi, 2004, p. 52). Brown (1978) intimated that home economists needed familiarity with existentialism if they hoped to help individuals and families confront life’s problems. With her suggestion that we should focus on the human condition, McGregor (2010) alluded to the merit of existentialism in the profession. Home economics practitioners are encouraged to take this philosophical conversation into their future.

References

Absurdism. (2014). In Philosophy Index. Retrieved from http://www.philosophy-index.com/existentialism/absurd.php

Allen, B., & Shearer, B. C. (2012). The scale for existential thinking. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 3, 21-27.

Behar, D. M. (2012). Existential issues. Pelham, NY: Westchester Purpose-Driven Therapy. Retrieved from http://www.westchester-therapist.com/pdt-existential-issues.html

Brown, M. M. (1978). A conceptual scheme and decision-rules for the selection and organization of home economics curriculum content. Madison, WI: Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction.

Brown, M. M. (1980). What is home economics education? [microfiche]. Minneapolis, MI: Minnesota University Department of Vocational and Technical Education.

Brown, M. M. (1985). Philosophical studies of home economics in the United States: Our practical-intellectual heritage (Volume II). East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University.

Brown, M. M. (1993). Philosophical studies of home economics in the United States: Ideas by which home economists understand themselves. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University.

Brown, M. M., & Paolucci, B. (1979). Home economics: A definition [mimeographed]. Alexandria, VA: American Association for Family and Consumer Sciences.

Burnham, D., & Papandreopoulos, G. [ca. 2012]. Existentialism. In J. Fieser & B. Dowden (Eds.), The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Martin, TN: University of Tennessee at Martin. Retrieved from http://www.iep.utm.edu/existent

Cohen, A. (2007, June 24). Woody Allen’s universe, still expanding, is as absurd as ever. The New York Times, Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2007/06/24/opinion/24sun3.html?_r=0

Corbett, B. (1985). What is existentialism? Retrieved from Webster University website: http://www2.webster.edu/~corbetre/philosophy/existentialism/whatis.html

Crowell, S. (2010). Existentialism. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford, CA: Stanford University. Retrieved from http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/existentialism

Existentialism and politics. (2014). In Philosophy Index. Retrieved from http://www.philosophy-index.com/existentialism/politics.php

Gardner, H. (1999). Intelligence reframed. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Harper, D. (2014). Online etymology dictionary. Lancaster, PA. Retrieved from http://www.etymonline.com

Heter, S. [ca. 2007]. Sartre’s political philosophy. In J. Fieser & B. Dowden (Eds.), The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Martin, TN: University of Tennessee at Martin. Retrieved from http://www.iep.utm.edu/sartre-p/

Hoffman, L. (2009). Freedom, responsibility, and agency. Los Angles, CA: Center for Existential Depth Psychology. Retrieved from http://www.existential-therapy.com/special_topics/Freedom_and_Responsibility.htm

Jickling, B., & Wals, A. (2012). Debating education for sustainable development 20 years after Rio: A conversation between Bob Jickling and Arjen Wals. Journal of Education for Sustainable Development, 6, 49-57.

Kahn, J. (n.d.). Utopia: On its ethics, politics, & economics: The good life - Greek philosophers teachings. Retrieved from http://www.skeptically.org/ethicsutility/id10.html

MacCleave, A. (1995). Voices from the opposite end of the theoretical spectrum: A response to Brown & Baldwin’s paper, The concept of theory in home economics. In M. M. Brown & E. Baldwin, The concept of theory in home economics (pp. 51-65). East Lansing, MI: Kappa Omicron Nu.

Marsh, C., & Willis, G. (1999). Curriculum (2nd ed.). Columbus, OH: Merrill Prentice Hall.

McGregor, S. L. T. (2005, November). [Review of the book A philosophy of home economics: Establishing home economics as a discipline for human protection, by F. Sekiguchi]. International Journal of Consumer Sciences, 29(6), 530-532.

McGregor, S. L.T. (2010). Locating the human condition concept within home economics [McGregor Monograph Series No. 201002]. Seabright, NS: McGregor Consulting Group. Retrieved from http://www.consultmcgregor.com/documents/publications/human-condition-monograph-2010.pdf

McGregor, S. L. T. (2014). Resistence to philosophy - Why aren't we taking up this aspect of practice? Paper presented at the International Federation for Home Economics Council Meeting (Pre-Symposium). London, Ontario. Retrieved from http://www.consultmcgregor.com/documents/research/IFHE_London_Symposium_Resistence_to_Philosophy.pdf

McNeil, J. D. (1977). Curriculum. Boston, MA: Little Brown.

Nickols, S., Ralston, P., Anderson, C., Browne, L., Schroeder, G., Thomas, S., & Wild, P. (2009). The family and consumer sciences body of knowledge and the cultural kaleidoscope. Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal, 37(3), 266-283.

Rohmann, V. (1999). A world of ideas: A dictionary of important theories, concepts, beliefs, and thinkers. New York, NY: Ballantine Books.

Sekiguchi, F. (Ed.). (2004). A philosophy of home economics. Fukushima, Japan: Koriyama Women’s University Press.

Smith, G. (1991). Home economics as a practical art. Preparing students for family life in a global society. THESA Newsletter, 32(1), 13-15. Retrieved from https://bctf.ca/thesa/pdf/Vol32_1Smith.pdf

Stangroom, J., & Garvey, J. (2005). The great philosophers. London, England: Arcturus.

Tuomi-Gröhn, T. (Ed.). (2008). Reinventing art of everyday making. Berlin, Germany: Peter Lang.

Vaines, E. (1994). Ecology as a unifying theme for home economics/human ecology. Canadian Home Economics Journal, 44(2), 59–62.

Vaines, E. (1998). A family perspective on everyday life: The heart of reflective practice. In K. Turkki (Ed.), Proceedings of the International Household and Family Research Conference (pp. 15–35). Helsinki, Finland: University of Helsinki, Department of Home Economics and Craft Science.

Vincenti, V. (2009). Exploring fundamental concepts for home economics and family and consumer sciences practice using A Philosophy of Home Economics by Fusa Sekiguchi. Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal, 38(1), 56-62.

Wals, A. (2010). Message in a bottle: Learning our way out of unsustainability. Inaugural lecture presented as UNESCO ESD Chair at Wageningen University. Wageningen, the Netherlands. Retrieved from http://groundswellinternational.files.wordpress.com/2010/12/learning-our-way-out-of-unsustainability.pdf

Wikipedia Encyclopedia. (2014a). Existentialism. San Francisco, CA: Wikipedia Foundation. Retrieved November 2, 2014 from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Existentialism

Wikipedia Encyclopedia. (2014b). Existential therapy. San Francisco, CA: Wikipedia Foundation. Retrieved November 7, 2014 from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Existential_therapy

Wikipedia Encyclopedia. (2014c). Facticity. San Francisco, CA: Wikipedia Foundation. Retrieved November 2, 2014 from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Facticity

Wiles, J., & Bondi, J. (2002). Curriculum development (6th ed.). Columbus, OH: Prentice Hall.

ENDNOTE

1. The author is only recently aware of post-postmodernism (aka metamodernism), a topic not included in this paper. Vermeulen and van den Akker (2010) explained that metamodernism is based on Plato's metaxy, which denotes movement between opposite poles, in this case modernism and postmodernism. They argued that such an approach is needed to respond to such wicked problems as climate change, the global financial crisis, the digital revolution, global political instability, and global health pandemics.

Sue L. T. McGregor,

Mount Saint Vincent University

Vija Dišlere,

Latvia University of Agriculture

Sue L. T. McGregor,

Mount Saint Vincent University

Sue L. T. McGregor,

Mount Saint Vincent University

Sue L. T. McGregor,

Mount Saint Vincent University

Sue L. T. McGregor,

Mount Saint Vincent University

Aesthetic Experiences, Bodily Being, and Enfolded Everyday Life

Henna Heinilä

Sue L. T. McGregor,

Mount Saint Vincent University

Peng Chen PhD, Higher Vocational Education College, China Women's University

Sue L. T. McGregor,

Mount Saint Vincent University

Dr. Mary Gale Smith

Sue L. T. McGregor,

Mount Saint Vincent University

|