|

Kappa Omicron Nu

FORUM

Categories of Sexual Harassment: A Preliminary Analysis

Catherine Amoroso Leslie, PhD

William E. Hauck, M.A.

© 2005

Contact:

Catherine Amoroso Leslie, PhD

Assistant Professor, Fashion School

Kent State University

P.O. Box 5190, Kent OH 44242

[email protected]

Phone (330) 672-0169 Fax (330) 672-3772

William E. Hauck, M.A.

Assistant Professor, Fashion School

Kent State University

P.O. Box 5190, Kent OH 44242

[email protected]

Phone (330) 672-0135 Fax (330) 672-3772

Abstract

Sexual harassment is a pervasive and costly problem for businesses,

government, and educational institutions. Throughout the past 20 years,

researchers have used a 5 group system to classify "sexual harassment"

behaviors. The purpose of this study is to explore the relevance of

these categories. Preliminary factor analysis of data from 276 female

college students indicates potential support for three, rather than

five categories of sexual harassing behaviors. Ongoing interdisciplinary

research will help Family and Consumer Sciences professionals to understand

how sexual harassment is perceived by individuals, families, and communities

and address it accordingly.

Note: This research was approved by the Kent State

University Institutional Review Board (IRB) to use human research

participants (Protocol Number 03-441).

Categories of Sexual Harassment: A Preliminary Analysis

Sexual harassment is a pervasive and costly problem for businesses,

government, and educational institutions with over 10,000 formal complaints

to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) per year. In

its broadest definition, sexual harassment is any form of unwanted

sexual attention (U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board, 1995). Claims

are often based on Title VII and Title IX of the Federal Civil Rights

Act of 1964, as Amended (Till, 1980). Since the passage of this legislation,

researchers and institutions have attempted to identify behaviors

and group them into operational categories that can be communicated

to employees and management.

The process of defining what constitutes illegal sexual harassment

began in the mid-1970s when the EEOC published official guidelines

(Till, 1980). According to the EEOC (1980), sexual harassment includes

unwanted behavior that is either physical or verbal in nature. The

EEOC also outlined criteria for determining whether or not an action

constituted unlawful behavior.

The EEOC guidelines set the stage; but, the process of identifying

specific sexual harassing behaviors and grouping them according to

severity began with the passage of Title IX, the primary statute which

prohibits sex discrimination in Federally assisted education programs

and activities (Till, 1980). Under the direction of the National Advisory

Council on Women's Educational Programs, Till (1980) collected descriptive

anecdotes from 166 college aged victims and others who were aware

of sexual harassment incidents. Data were used to identify five major

types of behaviors within the meaning of "sexual harassment."

The five distinguishable types of behaviors identified by Till (1980)

were:

1. Generalized sexist remarks or behavior

2. Inappropriate and offensive, but essentially sanction-free, sexual

advances

3. Solicitation of sexual activity or other sex-linked behavior

by promise of rewards

4. Coercion of sexual activity by threat of punishments

5. Sexual assaults

As part of an ongoing research project, Louise F. Fitzgerald and

several colleagues named the five categories of sexual harassment

previously identified by Till (1980). These were, in order of severity:

Gender harassment, Seductive behavior, Sexual bribery, Sexual coercion,

and Sexual assault (Fitzgerald, Shullman, Bailey, Richards, Swecker,

Gold, Ormerod, & Weitzman, 1988). Using these categories as a

foundation, Fitzgerald et al. (1988) developed the Sexual Experiences

Questionnaire (SEQ) that delineated 23 specific sexual harassing behaviors.

As a result of a series of focus groups, Fitzgerald et al. (1988)

modified the SEQ and added five new items. The revised instrument,

named the SEQ2, had a total of 28 items which were grouped into the

same five categories as Till (1980). After administering the SEQ2

to 307 female university employees, Fitzgerald et al. (1988) found

the instrument to be reliable. Since then, the SEQ2 has been used

to measure sexual harassing behaviors in various populations, including

female college students employed in the fashion retail workplace (Leslie

& Hauck, 2005; Workman, 1993).

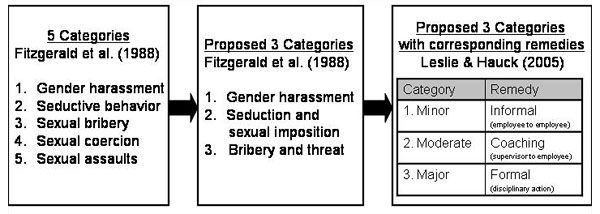

In their discussion, Fitzgerald, et al. (1988) suggested that factor

analysis of the SEQ2 indicated that a three-factor solution appeared

to be a more accurate grouping of sexual harassing behaviors than

the five proposed by Till (1980). The proposed groupings were: Bribery

and threat, Seduction and sexual imposition, and Gender harassment.

The three-category structure was further supported in subsequent studies

(Fitzgerald et al., 1988; Magley, Hulin, Fitzgerald, & DeNardo,

1999).

This study examined the three-category structure for sexually harassing

behaviors among college-aged women, those most vulnerable to be victimized.

Two hundred seventy-six female college students with work experience

in the fashion retail industry provided data on their experiences

through the SEQ2 (Leslie & Hauck, 2005; Workman, 1993). The data

were analyzed with factor analysis to examine sexual harassing behaviors

and categories. After six iterations, three factors emerged indicating

potential support for the three-category structure proposed by Fitzgerald

et al. (1988).

A practical application of a simplified grouping and labeling structure

can lead victims to identify, understand, and select an appropriate

remedy when faced with sexual harassment in the workplace. For example,

the three categories may be labeled as minimum, moderate, and major,

each with a corresponding set of potential remedies (see Figure 1).

Using a less-complicated grouping system may lead to better recognition

of sexual harassment in the workplace. To this end, ongoing research

will seek to explore categories of sexual harassment. By better understanding

sexual harassment in the workplace, Family and Consumer Sciences scholars

and practitioners can contribute to reducing this costly and pervasive

problem.

Figure 1: Categorical Model of Sexual Harassment

References

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. (1980). Discrimination

because of sex under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as

Amended. Washington, DC: EEOC.

Fitzgerald, L., Shullman, S., Bailey, N., Richards,

M., Swecker, J., Gold, Y., Ormerod, M., & Weitzman, L. (1988).

The incidence and dimensions of sexual harassment in academia and

the workplace. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 32, 152-175.

Leslie, C. A., & Hauck, W. E. (2005). Extent and

nature of sexual harassment in the fashion retail workplace: 10 years

later. Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal, 34(1),

7-33.

Magley, V., Hulin, C., Fitzgerald, L., & DeNardo,

M. (1999). Outcomes of self-labeling sexual harassment. Journal

of Applied Psychology, 84(3), 390-402.

Till, F. (1980). Sexual harassment: A report on

the sexual harassment of students. Washington, DC: National Advisory

Council on Women's Educational Programs.

U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board, Office of Policy

and Evaluation. (1995). Sexual harassment in the federal workplace:

Trends, progress, continuing challenges. Washington, DC: U.S.

Government Printing Office.

Workman, J. E. (1993). Extent and nature of sexual

harassment in the fashion retail workplace. Home Economics Research

Journal, 21 (4), 358-380.

Consumer Moral Ambiguity: The Gray Area of Consumption

Sue L. T. McGregor

Peer Review: A Filter for Quality

Dorothy I. Mitstifer

Mentoring Students in Cross-Specialization Teams

Dorothy I. Mitstifer

Consumerism as a Source of Structural Violence

Sue L. T. McGregor

Consumer Entitlement, Narcissism, and Immoral Consumption

Sue L. T. McGregor

A Satire: Confessions of Recovering Home Economists

Sue L. T. McGregor

The Nature of Transdisciplinary Research and Practice

Sue L. T. McGregor

Reflection Matters: Connecting Theory to Practice in Service Learning Courses

Mary E. Henry

What's It All About—Learning in the Human Sciences

Dorothy I. Mitstifer

Leadership Responsibilities of Professionals

Dorothy I. Mitstifer

Categories of Sexual Harassment: A Preliminary Analysis

Catherine Amoroso Leslie, William E. Hauck

Knowledge Management / Keeping the Edge

Dorothy I. Mitstifer

Super Kids Program Evaluation Plan

Nina L. Roofe

The Enigmatic Profession

Nina L. Roofe

The Wilberian Integral Approach

Sue L. T. McGregor

|