|

Kappa Omicron Nu

FORUM

Dorothy I. Mitstifer

Dr. Mitstifer is Executive Director of Kappa Omicron Nu Honor Society.

© Dorothy I. Mitstifer 2005

Contact: [email protected]

This

chapter introduces a leadership development model that raises the

question: Leadership for what? Leadership is about going

somewhere—personally and in concert with others in an organization1.

Although leadership is often discussed in terms of leader qualities and

skills, especially position (elected or appointed) leadership, the

matter of leadership as a responsibility of each professional receives

little attention. Organizations and programs do not flourish with one

leader in a group. Thus, more attention has to be paid to the definition

of leader as anyone willing to help (Wheatley, 2005). Leadership is not

about position only, but about taking responsibility as a member of a

group (whether 2-person or 60-person) to share leadership for the

organization’s well-being.

Despite

the investments in time, money, and energy, leadership development

programs in many organizations are often piecemeal, focused on aspects

in isolation (Ready, 2004). They may offer the latest competency

program, an up-to-date performance management system, a sophisticated

assessment instrument, the latest electronic learning package, and/or a

program built around available speakers and facilitators known to the

leadership development committee. In these approaches, there is also a

danger in focusing on local issues to the exclusion of broad, sweeping

issues of importance to the national or international perspective for

the organization. Then, too, we live in a world that is different and

changing so fast that former approaches just don’t serve the current

and future needs of organizations.

Each

organization needs to learn how to grow its own leaders, but it needs a

theoretical framework to accomplish this worthy objective. The South

American poet Machados declared, “The road is your footsteps, nothing

else” (Wheatley, 2005, p. 43). The leadership development model

described in this chapter is intended to guide your footsteps in a

direction that clarifies your personal and professional journey and

shares responsibility among colleagues for the well-being of your

organization. The following sections will discuss the basic components

of a leadership development model, a leadership theory, issue framing,

and a concluding section that ties everything together as a

comprehensive approach to leadership development.

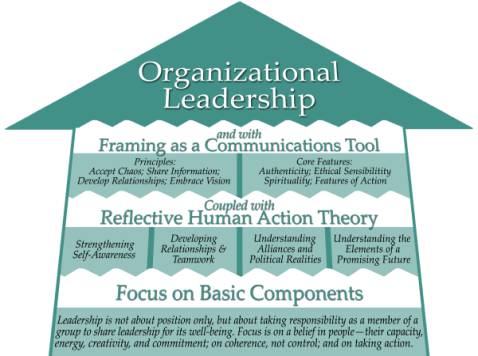

Basic Components of the

Reflective Human Action Leadership Development Model

If

the premise is accepted that an organization cannot succeed without

position leadership and group members sharing leadership

responsibilities, it is then incumbent upon each organization to

establish an intentional program to develop leadership skills at all

levels. Presently, pre-professionals and professionals, alike,

experience leadership development in a haphazard manner. In some ways,

leadership of a profession is more important than content to carry on

its mission and practice. The proposed Reflective Human Action (RHA)

Leadership Development Model (Figure 1) focuses on (a) strengthening

self-awareness, (b) developing relationships and teamwork, (c)

understanding alliances and political realities, (d) understanding the

elements of a promising future of the organization, and coupled with (e)

Reflective Human Action (RHA) leadership theory as its foundation and

framing as a communications tool. It is hypothesized that the model will

enable individuals to assume leadership responsibilities as

professionals. At its base this model states the philosophy that

underlies leadership; the next level includes the basic components of

leadership development that are coupled with theory and with competency

in framing—all leading to the overall objective: organizational

leadership. The following section explains the four basic components of

the Model.

Figure

1.

Reflective Human Action (RHA) Leadership Development Model

© 2005 by

Dorothy I. Mitstifer. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

I.

Strengthening self-awareness

People live in their own world of self-generating beliefs,

which are often untested (Ross, 1994). These beliefs are the product of

past experience and inferences from observations. Argyris (1990) labeled

this phenomenon the “ladder of inference,” a mental pathway based

upon observable data and experiences and composed of the data selected,

the meanings assigned, the assumptions made, conclusions drawn, beliefs

adopted, and actions taken. If all of these components are unquestioned

and untested, these inferences may lead to misguided beliefs. But

one’s self-awareness can be strengthened by reflection (becoming more aware of one’s own thinking and reasoning), advocacy (making one’s thinking and reasoning more visible to others), and inquiry (inquiring into other’s thinking and reasoning) (adapted from Ross,

1994, p. 245).

From abstract to concrete – Self-awareness can be defined as the ability to become the object of

one’s own attention, to evaluate self. It requires the ability to

reflect—to step back and take a hard look at one’s information,

perspectives, assumptions, conclusions, beliefs, actions. Writing or

journaling may be useful in getting in touch with self. Another method

is mental imagery, which offers the opportunity to see oneself as seen

by others. Or it may require a quiet natural setting or a guided

discovery process to free one to look inward. Feedback could be helpful

from someone with whom you have an open, trusting relationship. The

metaphor of a lens might be beneficial in looking at self. What lens am

I using to look at self? A telephoto lens could help to pick out a few

more elements, or a wide-angle lens could help me see the big picture.

Some questions might include: What is the influence of my style and

habits on others? What more information could I gather? What are

alternative perspectives and assumptions? What impact does more

information and alternative perspectives and assumptions have on

conclusions and beliefs? How might my actions change with more insight?

Ross (1994, p. 245) suggested the following questions that

can assist a group in testing beliefs:

§ What

are the observable data behind that statement?

§ Does

everyone agree on what the data are?

§ Can

you run through your reasoning? What is the basis of your

interpretation?

§ When

you said _______, did you mean _______?

The ladder of inference is a tool for examination of

one’s own beliefs and actions and contributes to a healthy climate for

reflection in organizational matters.

II.

Developing relationships and teamwork

Collaborative

leadership within an organization by definition requires that one’s

self-knowledge be applied in interaction with others to develop

relationships and teamwork. Collaboration is a worthy skill because it

provides many benefits: a unified approach, effective internal decision

making, reduced costs through shared resources, and more creative

outcomes (Weiss & Hughes, 2005). But collaboration is not easily

achieved. To improve collaboration, the issue of conflict must be

addressed. Differences in perspective, competencies, access to

information, and strategic focus cause conflict, so acknowledgement and

development of processes to manage it are necessary precursors to

effective collaboration. By exploring all of the differences, conflict

situations produce benefits by providing new insights and possibilities

for improving organizational decisions and outcomes.

Effective

collaboration requires both individual and network expertise.

Connectivity gained through networks produces synergistic outcomes, but

it has its downside as well: countless meetings can drain time and

energy. So, there is a “need to develop a strategic, sophisticated

view of collaboration . . . .” (Cross, Liedtka, & Weiss, 2005).

The appropriate degree of connectivity must be determined for achieving

specific results required of the organization. Some tasks will require

all players while others can be assigned to specific networks, all the

while maintaining openness and communication to ensure understanding and

transparency.

From

abstract to concrete – Teamwork relies first of all

upon trust—a firm reliance on the integrity, ability, and character of

team members. Trust develops through sharing: telling and listening

about personal events and feelings; through vulnerability: being

perceived as having the capacity to err and willingness to acknowledge

it; through loyalty: making a commitment to goals and other members; and

through accepting others: welcoming the uniqueness of others. Thus team

building requires time to get to know each other, in informal and fun

environments (family picnics, team sports events, day-long trips) or in

a more formal team-building program. To guard against groupthink

(converging on agreement regardless of quality), there is a need to

ensure that the following roles of team members are functioning:

knowledge contributor, process observer, collaborator, people supporter,

challenger, listener, mediator, and gatekeeper.

An

effective team will create strategies, policies, and structures to guide

its work; identify the vision, values, and goals to respond to the

perceived need; develop action plans to achieve the goals, including a

timetable and assignment of tasks according to expertise; monitor and

evaluate the implementation; use feedback to refine plans if necessary;

communicate progress; and celebrate accomplishments. High performance is

gained through shared leadership, alignment of function and purpose of

the team, focus on tasks, shared responsibility, innovation and

creativity, diversity of ideas and expertise, effective problem solving,

open and honest communication, and responsiveness to needs and

opportunities. In contrast, teams need to be aware of pitfalls and

possible strategies if they are encountered. Team members working

independently or at cross-purposes may be prevented by making sure that

the vision and goals accomplish personal and team goals. Turf battles

slowing or stopping project progress may require open communication

regarding the conflict and redistribution of roles and responsibilities.

Negative, manipulative, or secretive interactions probably indicate the

need for more attention to team-building activities as well as open

communication.

Internal

team leaders (appointed or elected by team members) know that you

can’t force collaboration, but you can expect it. It requires

discipline and dogged persistence in expecting collaborative behavior.

When leaders “consistently ask questions that remind people of those

expectations, they tend to get what they expect” (Linden, 2003, p.

47). A collaborative leader should be able to

§ Articulate the project’s purpose

in a way that excites others.

§ Be an effective convener: get the

appropriate people to the table and keep them there.

§ Help the participants see their

common interests and the benefits possible through joint effort.

§ Generate trust.

§ Help the participants design a

transparent, credible process.

§ Assist the participants in win-win

negotiations to meet three related interests (needs of each partner, of

the product they are creating, and of the relationships involved).

§ Make relationship building a

priority for the group.

§ See that there’s a senior champion

[external leader] of the effort.

§ Help everyone engage in

collaborative problem solving and make creative use of their diverse

viewpoints when differences arise.

§ Celebrate small successes; share

credit widely.

§ Provide confidence, hope, and

resilience. (Linden, 2003, pp. 42-44)

The above

tasks must be accompanied by the disposition to have persistence,

energy, and resolve; passion about achieving a collaborative outcome;

the ability to pull others rather than push them in a collaborative

direction; and the ability to think systemically and see the

interconnections (Linden, 2003, p. 45).

It should

be recognized that involving persons in a group activity does not make a

team. Equally important is the realization that teamwork may not always

seem efficient, but it is likely to be most effective.

III. Understanding alliances and political realities

Relations,

between and among people, are often uncertain, fluid, and complex. These

relationships often include alliances formed on the basis of values and

interests of a core of like-minded individuals. Thus, an organization

needs to examine the alliances in the group to find the mutual points of

agreement upon which to build trust. Although these alliances may be

political realities, it isn’t useful to label their activities as

political. So-called political intelligence, however, is needed to

identify how relationships are likely to affect success (Ciampa, 2005).

Political skills include the use of power and influence to enhance or

protect interests, thus group members need to be encouraged to go out of

their way to help the group find ways to be sensitive to the various

points of view and to be respectful of diverse spheres of interests.

Efforts need to be made to ensure that interactions and group processes

are transparent so that trust can build.

From

abstract to concrete – Politics

is the procedural dimension, the art and science of making choices about

the “means to the end,” in every human equation. Although the end can’t justify all

means, some actions dismissed as “politics” might be

misunderstandings or miscommunication. Because politics stems from a

diversity of interests, it is in the best interests of the organization

to explore the processes by which people engage in politics (Ratzburg,

n.d.):

- Where

the activity take place—inside or outside the organization

- The

direction of influence—vertically or laterally in the organization

- The

legitimacy of the action—generally

accepted differences or threats

Political

behavior is often related to the investment persons have in the

organization, the alternatives they perceive they have, the level of

trust, and the perceived efficacy in influencing the group. Additional

contributions are ambiguous goals, scarce resources,

irrational decision-making processes, and organizational change.

Limiting factors have to do with open communication, reduction of

uncertainty, and increased awareness of the issues and activities of the

organization.

Those

who effectively use political intelligence accurately “read”

political currents but don’t label them that way, recognize how

relationships affect issues and decisions, engage others to go out of

their way to help, and don’t seem self-serving. Holbeche

(2004) describes constructive political behavior as

- Establishing

effective relationships

- Understanding

individual agendas

- Creating

win-win situations

- Acting

in a principled way

- Building

strong support for constructive ideas

- Building

a personal reputation

- Treating

everyone fairly

- Influencing

others rather than directly using power

The

use of power and influence is critical in examining political realities.

Power defined as expenditure of energy toward action—the decision, the

passion, the self-determination,

and the will—is the invisible spirit behind commitment (Terry, 1993).

If conducting a power audit, an organization would first check the

energy level of the group. Is it lively and engaged, or is it flat and

dull? Is there anger, joy, frustration, or hostility? Is participation

and involvement high or low? Second, are all the critical stakeholders

represented? Third, what is the capacity to make and keep decisions?

Power is an essential part of action and of leadership. In order for

power to be dynamic, flowing, and changing over time, it should be

examined under the following themes (Terry, 1993, p. 74):

- Power

requires a prevailing sense . . . that energy, whether individual or

collective, is legitimate and appropriate.

- Power

requires a deep sense

of personal or collective self-determination.

- Power

involves outward expression.

- Power

translates into institutional forms such as reflection, debate,

voting, and consensus making.

- Power

requires current political information and skills in order to assess and engage in a current context.

- Power

depends on retrospective ownership of past actions.

Positive

alliances are based upon effective communication, treatment of allies as

equals, professionalism, and time spent in listening and strategizing.

Other behaviors

that contribute to the development of alliances include (Heathfield, n.d.):

- Producing

high quality work

- Choosing

“battles” wisely

- Keeping

promises

- Resolving

conflicts and disputes immediately

- Being

an ally—giving credit and support

- Talking

directly to an ally if you have a problem

By understanding alliances and

political realities and using constructive political behavior, leaders

can make things happen, unblock barriers to change, create buy-in on

organizational initiatives, produce greater organizational cohesion, and

speed up decision making. But leaders have the responsibility of

creating a receptive environment by using persuasion constructively.

“Persuasion promotes understanding; understanding breeds

acceptance; acceptance leads to action” (Garvin & Roberto, 2005,

p. 112).

IV. Understanding the elements of a promising future

Vision,

opportunity, and risk could be called the hallmarks for establishing

promising futures (Price, 2004). Vision and direction need to be well

understood if organizations are to have a clear sense of where they are

going and to focus attention on this vision. With vision, smart choices

can be made with the end result in mind. Short-term goals are geared to

the larger picture. “Vision allows for a long-term proactive

stance—creating what we want—rather than a short-term reactive

stance—getting rid of what we don’t want” (Blanchard & Stoner,

2004, p. 22).

From

abstract to concrete - When pushing the boundaries, there

is always an element of risk. In this fast-paced world, we face

diversity, contradictions, and complexity. How do we converge our

energies to balance the opportunities and risks in the interest of a new

vision and excellence? It will be important to find answers to the

questions of “What is important?” “What is best?” “Who are we

impacting?” “What will be the consequences?” A promising future

offers these challenges; answers come from looking at current realities

and visions, using the data to establish core beliefs, converting

beliefs into principles, and proposing practices to implement the

beliefs (Donaldson, 2000). With courage and perseverance, leaders of an

organization can use these elements to define and recreate the entity

for a promising future.

Various

strategies or models are available to guide future planning. Scenario

thinking (Scearce & Fulton, 2004) clarifies the issues, explores the

driving forces of change, synthesizes the driving forces to create

scenarios, develops a strategic agenda based on patterns and insights

that emerged in the scenarios, and creates a mechanism to monitor shifts

in the environment. This process is sometimes called scenario analysis.

Strategic

planning models come in various forms. Most of them include a values

audit, formulation of mission and vision statements, external scan, a

performance audit, a gap analysis, strategic goals, an action plan for

strategic direction, a communication process for the plan, a process for

monitoring the implementation and continuous environmental surveillance,

and evaluation and control (Pfeiffer, Goodstein & Nolan, 1985, 1993,

1998; McNamara, n.d). Other models include Preferred Futuring (Lippitt,

1998), Future Search (Weisbord & Janoff, 1995), and Open

Space Technology (Owen, 1997).

Strategic

thinking has gained currency over planning because of the tendency to be

“overly concerned with extrapolation of the present and the past as

opposed to focusing on how to reinvent the future” (Lawrence, 1999).

Leidka (as cited in Lawrence, 1999) proposed a closed circle model that

incorporates both notions: current reality®strategic

thinking: disrupting alignment®desired

future®strategic

planning: creating alignment. The following discussion describes

selected salient elements in establishing a promising future.

A mission statement describes why your organization exists, its

basic purpose. The intent is philosophical; it is a statement about

ends—products, outputs, or other effects. The statement must be broad

in detailing the mega-end—the difference the organization will make

for its beneficiaries. Sub-ends will be developed to reach the mega-end.

Carver (1993, 1997) is unusual in promulgating short and to the point

mission statements. Although this approach calls for more rigor, it

provides clarity in defining “what good” for “which people” in a

long-term perspective. The following checklist measures effectiveness

(adapted from Carver, 1993, p. 5):

§ Ends, not means

§ Effects, not efforts

§ Outcomes (nouns),

not verbs

§ Brevity, not padded

paragraphs

§ Accuracy, not

cosmetics

§ Not too broad or too

narrow

§ Net value added, not

endless summary

A vision statement includes a significant purpose, a picture of the

future, and clear values. Because a purpose is your organization’s

reason for existence, it must inspire excitement and commitment in order

to unleash productive and creative energy. A picture of the future

should focus on a concrete end result. Clear values describe the

behavior guidelines for daily decisions. In order to be effective,

however, the vision statement must be created through broad dialogue,

communicated often, and lived through daily actions.

The

purpose of a vision statement is to create an aligned organization where

everyone is working together toward the same desired ends. The vision

provides guidance for daily decisions so that people are moving in the

right direction, not working at cross-purposes with one another.

(Blanchard & Stoner, 2004, p. 23)

Environmental

scanning is the exploration phase of thinking and planning for the

future and a large part of understanding the fit between an organization

and its external environment, “in light of the mission, organization

strengths and limitations, and external challenges and opportunities”

(Duttweiler, 2004). In addition to the SWOT analysis (strengths,

weakness, opportunities, and threats) most commonly used, there are

other techniques: situational analysis, assets mapping, concept mapping,

issue analysis/mapping, stakeholder/political mapping, SPOT (strengths,

problems, opportunities, and threats), among others. The task at hand

and the preferences of the planning group are relevant in selecting the

appropriate process.

Strategic

goalsto establish a promising future arise from prioritizing

values and needs identified during the strategic thinking and planning

process. To ensure follow-through, action planning operationally

defines each goal, the action steps which describe the what and how,

the resources required, who is responsible, when each step will be completed, and how evaluation will be

conducted. Action plans help teams stay organized, coordinate their

activities, and keep projects to implement the future on schedule. A simple Excel spreadsheet can be used to display the data. Other

alternatives include a Gantt chart to show an overview of tasks. The

Gantt includes the tasks on one side and columns of weeks, days, or

months on the other. Horizontal bars are drawn to indicate the period

each task will be performed. A PERT chart is a flow diagram of activity

boxes to depict tasks.

Although understanding the elements of a promising future is the most

important of the four basic components of leadership development, this

stage cannot be reached without the other three—self-awareness, healthy relationships and effective teamwork, and

political skill. That’s a tall order. The need for leadership

is clear. Each organization must decide what it is going to do about it.

The four basic components of the RHA Leadership Development Model, in

and of themselves, will not ensure excellence because leadership is a

multidimensional and multi-layered construct. A comprehensive theory and

philosophy is necessary to provide a foundation for leadership.

Leadership

Theory

The previous

chapter described the theoretical framework of Reflective

Human Action (Figure 2),

a leadership theory and philosophy promulgated by Kappa Omicron Nu, and

authored by Frances E. Andrews, Dorothy I. Mitstifer, Marcia Rehm, and

Gladys Gary Vaughn (1995). This theory was based on the work of Terry

(1993) and Wheatley (1994). To recap—the principles for leadership

practice are

§ Accept chaos

§ Share information

§ Develop

relationships

§ Embrace vision

and the core

features of Reflective Human Action are

§ Authenticity

§ Ethical sensibility

§ Spirituality

§ Features of action

Figure 2. Reflection Human

Action Model

Ó 1995 by Kappa Omicron Nu. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

These principles and core features are themes throughout

the four basic components of leadership development discussed above.

Hesselbine (2005, p. 4) succinctly makes the case for these themes:

“We need leaders who believe and embody in concept, language, and

action that leadership is a matter of how to be, not how to do . . . .

“

Reflective Human Action is a state-of-the-art comprehensive theoretical framework; its action

wheel is an astounding diagnostic tool for naming and framing

organizational issues and determining the strategic interventions

necessary to address the identified issues. A professional development

module and an online free course (kon.org/rha_online_files/rha_online2.htm) are available to learn about the leadership theory and for use in

self-managed life change.

Issue

Framing with Reflective Human Action Theory

“Leadership

. . . is grounded in the wisdom of knowing what is really happening,

which often means moving beyond fixing and managing” (Terry, 2003, p.

34). Leaders need to understand and interpret what is going on in an

organization and how individuals should relate to it; these actions

define issue framing. The particular means of accomplishing these two

tasks has either a beneficial or negative impact on what is done about

the issue or conflict. Thus, in an effective collaborative leadership

style, a core skill is the ability to name and frame issues in

organizations. A process is needed to learn the concerns people have

about an issue; identify the consequences, costs, and benefits

associated with various options for action regarding the issue; work

through inherent conflicts; and find shared direction or common ground

for action. In contrast to framing as the hot topic in political

circles, which often seeks to win the “framing game,” this

skill fulfills a powerful role in groups by evoking greater

understanding of diverse perspectives, embracing a wider range of views,

and finding intelligent choices about a shared future.

Terry

(1993, 2003) made a significant contribution by focusing on the

importance in leadership of answering the question of what is really

going on. Using his Action Wheel (1993) (see Figure 2 in previous

chapter), the process of framing diagnoses the issues and identifies the

interventions. In the complex world of today, the deep questions of

identity and meaning must be answered by engagement of spirit. Thus

leadership must make a lifetime commitment to answer the tough questions

of what is really going

on. Terry’s six features of action—mission, meaning, existence,

resources, structure, and power—require the overarching skill of issue

framing for fulfillment of human action. Whether or not all

features of action have been attended to and are functioning well, the

group is united in thinking, being, and doing.

From

abstract to concrete – Terry’s Action Wheel

facilitates the function of framing. The first step is to diagnose the

issue by examining the dialogue to name and frame it and then to use the

intervention indicated by the arrow to address the issue. Two cases

follow to explain the process.

Case 1 - Some of the

faculty members in the unit (or members of a student club) are upset.

Statements such as “The decisions are already made.” “Why

doesn’t someone just do something?” “Morale is really bad; the

wrong people seem to be making decisions.” “We can’t get things

done. I don’t know what’s happening.” These are cues to the issue

of POWER. The intervention should deal with MISSION. There are no

shortcuts; mission work is time consuming and hard work. It must involve

all members; considerable dialogue about goals—the ends—of the

organization is required. What are the outcomes that this organization

wants to achieve? What is it in business for? The more the involvement,

the more the satisfaction with decisions about mission.

Case 2 - Mildred is

a new administrator and she wants to balance the needs of her department

with the greater good of the institution. She has determined that before

she decides what changes are needed she will interview selected

employees to get a feel for their concerns. To her surprise, there

seemed to be a theme: “We can’t operate; there seems to be too much

red tape.” “There doesn’t seem to be any coordination.” I

don’t know how decisions are made.” “I think our department is

poorly organized.” This feedback indicates that the issue is

STRUCTURE; therefore the intervention should deal with POWER—with who

provides the energy for action. Examination of the power relations as

discussed previously in Component III needs to involve the whole group

in conducting a power audit, addressing personal and collective needs

and desires, and exploring ways to share power through constructive

political behavior.

“All

aspects of the model [Action Wheel] are implicitly present in every act.

Therefore, all features of action must eventually be addressed in any

proposed action” (Terry, 1993, 91-92). Thus, the organization needs to

address all features of action; a change in one affects all the others.

No organization is “fixed” once and for all; the dynamic nature of

organizations requires continuous and productive activity to ensure

viability over time.

Framing

could be described as a communication tool for everyone working on an

issue or conflict. The objective is to redefine the perspectives,

values, and assumptions about issues to become more inclusive and

mobilizing to individuals in the group. The social context is created

for win/win choices about direction. Communication in the form of

conversation is a key element in forging organizational futures. In her

book, Turning to One Another:

Simple Conversations to Restore Hope to the Future, Wheatley (2002,

p. 35) noted that

It is difficult to

give up our certainties—our positions, our beliefs, our explanations.

These help define us; they lie at the heart of our personal identity.

Yet I believe we will succeed in changing this work only if we can think

and work together in new ways. Curiosity is what we need. We don’t

have to let go of what we believe, but we do need to be curious about

what someone else believes.

The

ability to listen without judgment needs to accompany the curious mind.

It isn’t the differences that divide; it’s judgments that do.

Listening for differences will create uncertainty, but “We can’t be

creative if we refuse to be confused. Change always starts with

confusion; cherished interpretations must dissolve to make way for the

new” (p. 37). From diversity a group can gain a rich array of ideas

and possibilities for finding common ground.

Atlee (n.d.)

described several additional communication strategies2 for

framing issues. In all of the processes, inclusion and engagement of

diverse people and perspectives produce common ground, with underlying

shared needs, spirit, and experience. Even if win/win solutions are not

found, the complexity of issues will have been uncovered, and

participants will have gained an appreciation for the difficult task of

making some decisions.

Bringing

It All Together

The

professed intention of this chapter was to describe the RHA Leadership

Development Model for developing professional leadership. After the four

components of the model were explored and juxtaposed with Reflection

Human Action theory, the overarching skill of issue framing was

discussed as a communication tool for mobilizing leadership action. When

responsibility is widely shared, leadership efforts are successful for

at least ten reasons (adapted from Terry, 1993, pp. 286-287):

-

A consensus is formed on desired outcomes.

-

No one loses.

-

Ownership is pooled.

-

Fear and hope combine to motivate cooperation.

-

People make things happen.

-

Non-positional leaders fill key roles.

-

Reliable information is gathered.

-

A flexible system of self-direction is used.

-

Individual talents are tapped.

-

Individuals with initiative and entrepreneurial spirit are

involved.

The

RHA Leadership Development Model focuses on a belief in people—their

capacity, energy, creativity, and commitment; on coherence, not control;

and on taking action. Organizations depend upon these factors to ensure

their endurability and viability in the future. But most important of

all, organizational endurability depends upon having a model to organize

its leadership development process and upon inviting broad participation

and engagement in rethinking, redesigning, and restructuring the

organization to achieve its mission. Taken together, leadership and

broad participation can create a sense of community.

However,

the natural instinct for community does not necessarily lead to

organizational strength and endurability. Indeed, various cultures

(including professions) are increasingly creating specialty islands to

protect themselves from difference. Wheatley (2001, 2005) holds that

this phenomenon can be traced to the mistaken assumption that

organizations are machines. For example, the language of tool, build,

drive, and reengineer—all imply machine characteristics.

Instead, a different ideal is surfacing—organizations as adaptive,

flexible, self-renewing, resilient, learning, and intelligent. These

attributes are found in living systems—self-organizing systems.

Organizations

need to adopt characteristics of a self-organizing system and to erase

all traces of command and

control.

Self-organizing

systems have what all leaders crave: the capacity to respond

continuously to change. In these systems, change is the organizing

force, not a problematic intrusion. Structures and solutions are

temporary. Resources and people come together to create new initiatives,

to respond to new regulations, to shift the organization’s processes.

Leaders emerge from the needs of the moment. (Wheatley, 2005, p. 33)

It

is the nature of self-organizing systems to be disturbed by outside

information, not directed by it. The sense-making capacity comes from

within the system. “This explains why organizations reject reports and

data that others assume to be obvious and compelling” (p. 37). Thus,

the system (organization) has to develop its own identity—a coherent

center and clarity about what sustains the organization through

turbulent times. The organization’s identity is formed through clarity

about vision, mission, and values and a current interpretation of its

history, present decisions and activities, and its sense of its future.

Such clarity of purpose then enables the organization to reach out to

its customers, partners, and others to gather information, develop

effective relationships, and demonstrate that its identity truly directs

its actions.

When

an organization self-organizes as a living system,

. .

. it develops shared understanding of what’s important, what’s

acceptable behavior, what actions are required, and how these actions

will get done. It develops channels of communication, networks of

workers, and complex physical structures. And as the system develops,

new capacities emerge. Looking at this list of what a self-organizing

system creates leads to the realization that the system can do for

itself most of what [position] leaders have felt was necessary to do to

it. (Wheatley, 2005, p. 66)

Lest

there is an implication that there is no place for the position leader,

organizations do need a chief leader to create a receptive environment

for creative thinking and experimentation, support self-organizing

responses, provide information and resources, create connections, and

keep the focus on who the organization wants to be and what it wants to

accomplish. Position leaders also need to coach and develop people, keep

the team vision alive, energize with a positive outlook, insist on

transparency, make hard decisions when necessary, probe and question,

inspire risk-taking, and celebrate to recognize contributions (Welch,

2005).

The

new worldview of organizations as living systems affects position

leaders in profound ways (Wheatley, 2001, pp. 15-19). The following

principles guide their work:

-

Meaning engages creativity – if we want people to be

creative we must uncover meaningful issues.

-

Depend on diversity – a mosaic of perspectives comes from

identifying differences.

-

Involve everybody who cares – the only way to know what

will work is to invite everyone into the design process.

-

Diversity is the path to unity – a group can come together

as it recognizes its mutual interests.

-

People will always surprise us – people come together

through the act of listening.

-

Rely on human goodness – the impossible can be done through

creativity, caring, and human will.

The

better nature of humans rises, according to Wheatley, because we are

beginning to give up treating people as machines.

We are our only hope for creating a future worth working for. We can’t go it

alone, we can’t get there without each other, and we can’t create it

without relying anew on our fundamental and precious human goodness.

(2001, p. 20)

In

summary, then, the RHA Leadership Development Model is intended to bring

it all together by choreographing the interaction among layers—the

philosophy that underlies leadership, the basic components of leadership

development, leadership theory, and issue framing—to offer a

comprehensive approach to leadership development. A model is only a

beginning for organizational leadership. You are invited to join your

colleagues on the journey—one footstep at a time.

Footnotes:

1 Organization in this chapter refers to all kinds of informal and formal groups: neighborhoods, communities, agencies,

professions, institutions, corporations—even families.

2 Additional

communication strategies for framing issues:

National Issues Forum (NIF) and

Study Circles – The NIF and Study Circles techniques employ deliberative

sessions based on issue books or discussion guides developed in advance

by leaders who produce briefings that are unbiased and engaging. These

briefings describe the context, some of the underlying issues within the

issue, three to five approaches to the issues, arguments pro and con,

and notes on the values and trade-offs associated with each approach.

When participants can find their own values in the approaches, they can

better listen to each other’s perspectives and are less likely to be

stuck in narrow opinions. See www.nifi.org and www.studycircles.org.

Negotiation

and Mediation – Conflict is framed in terms of interests. A moderator helps

people clarify and agree on legitimate interests so that the group can

work on searching for solutions to embrace all interests. Fisher and

Ury’s “Getting to Yes” is explained at www.colorado.edu/conflict/peace/example/fish7513.htm.

Nonviolent

Communication – Conflict is framed in terms of unmet needs. A facilitator

works to clarify the unmet needs through questions, empathic

imagination, and reflective listening. See www.co-intelligence.org/P-nonviolentcomm.html.

Dynamic

Facilitation – A

choice-creating process of framing and reframing evolves dynamically

during conversation. Attacks are resolved through questions such as

“So, what’s your concern?” “What do you think should be done

about that?” The conversation continues by charting concerns, possible

solutions, problem statements, and data. Framing unfolds through

interaction that follows the group’s energy and evolving

understanding. See www.co-intelligence.org/P-dynamicfacilitation.html.

Consensus

Process – An issue is

framed and reframed until a new collective frame emerges from the group.

Special attention is paid to ensure that everybody’s concerns are

adequately addressed. Through this means a final decision will have more

wisdom and broad support. See www.co-intelligence.org/P-consensus.html.

References:

Andrews,

F. E., Mitstifer, D. I., Rehm, M., & Vaughn, G. G. (1995). Leadership:

Reflective human action - A professional development module.

East Lansing, MI: Kappa Omicron Nu.

Argyris,

C. (1990). Overcoming

organizational

defenses. Needham, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Atlee,

T. (n.d.). Framing

issues for battle and collective intelligence.

Retrieved February 26, 2005 from The Co-Intelligence Institute website: www.omplace.com/articles/tom_atlee35.html).

Blanchard,

J., & Stoner, J. (2004, Winter). The vision thing: Without it

you’ll never be a world-class organizations. Leader

to Leader, 31,

21-28.

Carver,

J. (1993). Evaluating the mission statement. Board

Leadership, 5, 1,4-5.

Carver,

J. (1997). Boards

that make a difference, 2nd.

ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Ciampa,

D. (2005, January). Almost ready: How leaders move. Harvard

Business Review Special Issue, 83(1),

46-53.

Cross,

R., Liedtka, J. & Weiss, L. (2005, March). A practical guide to social networks. Harvard

Business Review, 83(3),

124-132.

Donaldson,

G. A. (2000, April). A promising future for every student: Maine invests

in secondary school reform. NASSP

Bulletin.

Duttweiler,

M. (2004). Environmental

scanning principles and processes. Cornell

Cooperative Extension. Retrieved June 5, 2005 from http://www.cce.cornell.edu/admin/grogram/documents/scanintr.htm.

Garvin,

D. A., &

Roberto, M. A. (2005, February). Change through persuasion. Harvard

Business Review, 83(2),

104-112.

Heathfield,

S. M. (n.d.) Why

you need allies at work. Retrieved

June 5, 2005 from http://humanresources.about.com/cs/workrelationships/a/workallies_2.htm.

Hesselbine,

F. (2005, Winter). Leader

to Leader, 35,

4-5.

Holbeche,

L. (2004). The

power of constructive politics.

Horsham, UK: Roffey Park.

Lawrence,

E. (1999). Strategic

thinking: A discussion paper. Retrieved

on June 5, 2005 from http://www.psc-dfp.gc.ca/research/knowledge/strathink_e.htm.

Linden,

R. (2003, Summer). The discipline of collaboration. Leader

to Leader, 29,

41-47.

Lippitt,

L. L. (1998). Preferred

futuring. San

Francisco: Berrett-Koehler.

McNamara,

D. (n.d.) Strategic

planning (in nonprofit or for-profit organizations). Retrieved

June 5, 2005 from http://www.managementhelp.org/plan_dec/str_plan/str_plan.htm

Owen,

H. (1997). Open

space technology: A user’s guide. San

Francisco: Berrett-Koehler.

Pfeiffer,

J. W., Goodstein, L. D., & Nolan, T. M. (1985). Understanding

Applied Strategic Planning: A Manager’s Guide. San

Diego: University Associates, Inc.

Pfeiffer,

J. W., Goodstein, L. D., & Nolan, T. M. (1993). Applied

Strategic Planning: How to develop a plan that really works.

New York: McGraw-Hill.

Pfeiffer,

J. W., Goodstein, L. D., & Nolan, T. M. (1998). Applied

Strategic Planning: An Introduction. NewYork: Wiley.

Price,

K. (2004, November). Viewpoint. Bridge

Builder.

Ratzburg,

W. H. (n.d.). Defining

organizational politics. Retrieved

June 5, 2005 from http://www.geocities.com/Athens/Forum/1650/htmlpolitc01.html?20054.

Ready,

D. A. (2004, December). How to grow great leaders. Harvard

Business Review, 82(12),

93-100.

Ross,

R. (1994). The ladder of inference. In P. M. Senge, A. Kleiner, C.

Roberts, R. B. Ross, B. J. Smith. The

fifth discipline fieldbook: Strategies and tools for building a learning

organization.

New York: Currency/Doubleday.

Scearce,

D., & Fulton, K. (2004). What

if? The art of scenario thinking for nonprofits. San

Francisco: Global Business Network.

Terry,

R. (1993). Authentic

Leadership: Courage in Action. San

Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Terry,

R. (2003, Winter). Leadership in a shifting world. Leader

to leader, 26, 32-37.

Weisbord,

M. R., & Janoff, S. (1995). Future

search: An action guide to finding common ground in organizations &

communities. San

Francisco: Berrett-Koehler.

Weiss,

J., & Hughes. J. (2005, March). Want collaboration? Accept—and

actively manage—conflict. Harvard

Business Review, 83(3),

93-101.

Welch,

J. with Welch, S. (2005, April 4). How to be a leader. Newsweek,

CXLV(14),

45-48.

Wheatley,

M. J. (1994). Leadership

and the new science.

San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler.

Wheatley,

M. J. (2001, Spring).

Innovation means relying on everyone’s creativity. Leader

to Leader, 20, 14-20.

Wheatley,

M. J. (2002). Turning

to one another: Simple conversations to restore hope to the future. San

Francisco: Berrett-Koehler.

Wheatley,

M. J. (2005). Finding

our way:

Leadership for an uncertain time. San

Francisco: Berrett-Koehler.

Consumer Moral Ambiguity: The Gray Area of Consumption

Sue L. T. McGregor

Peer Review: A Filter for Quality

Dorothy I. Mitstifer

Mentoring Students in Cross-Specialization Teams

Dorothy I. Mitstifer

Consumerism as a Source of Structural Violence

Sue L. T. McGregor

Consumer Entitlement, Narcissism, and Immoral Consumption

Sue L. T. McGregor

A Satire: Confessions of Recovering Home Economists

Sue L. T. McGregor

The Nature of Transdisciplinary Research and Practice

Sue L. T. McGregor

Reflection Matters: Connecting Theory to Practice in Service Learning Courses

Mary E. Henry

What's It All About—Learning in the Human Sciences

Dorothy I. Mitstifer

Leadership Responsibilities of Professionals

Dorothy I. Mitstifer

Categories of Sexual Harassment: A Preliminary Analysis

Catherine Amoroso Leslie, William E. Hauck

Knowledge Management / Keeping the Edge

Dorothy I. Mitstifer

Super Kids Program Evaluation Plan

Nina L. Roofe

The Enigmatic Profession

Nina L. Roofe

The Wilberian Integral Approach

Sue L. T. McGregor

|