Preservation and Accessibility: Finding Common Ground at the Zarah Hotel

Stefanie Hetzke

Kansas State University

Abstract

The guidelines of the preservation movement and the Americans with Disabilities Act Accessibility Guidelines (ADAAG) are on opposite ends of the design spectrum. Saving historic environments that are often not accessible is the main goal of the preservation movement. The ADAAG is concerned with making sure all environments are accessible. This paper looks at how the preservation movement can save historic environments and make them accessible without compromising historic integrity.

Introduction

America is full of culturally, historically, and architecturally important buildings and structures. Many of these buildings are worth saving because of their ability to tell an important story about the development of this country�s history. Beyond this, many of these buildings should be saved because they can be viable parts of the community in which they are located. However, in order to fulfill their potential, these buildings are expected to meet current building and safety codes. Since the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), accessibility up to and throughout the interiors of these buildings has become part of the code standards that must be met. The modifications that are required for historic buildings to become accessible often destroy much of the historic fabric and character of the buildings. Preservationists and code officials are often at odds when it comes to meeting the requirements of Title III of the ADA. This is especially true when a commercial building, such as the Zarah Hotel building in downtown Great Bend, Kansas, is rehabilitated to incorporate contemporary uses and again become a revenue producing building. Maintaining the historic integrity and character of the building while allowing for persons with disabilities to access the goods and services provided within the building is the challenge facing preservationists everywhere. Preservationists and developers must take a closer look at the differences between the philosophies of preservation and accessibility, solutions to this challenge, and how those solutions affect an historic commercial structure such as the Zarah Hotel.

Gathering Information: The Preservation Movement���������

The preservation of historic structures in the United States started over a century ago with the saving of President Washington�s home, Mount Vernon (Tyler, 2000). Since that time, the philosophy of the preservation movement has grown to include not only the culturally important monuments of our history but also the buildings that tell the story of small parts of history, are architecturally important to our culture, and have useful life yet to contribute. Preserving the historic buildings contributes much to American society. The Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, in its 1979 study The Contribution of Historic Preservation to Urban Revitalization, concluded that preservation of buildings within historic districts contributed to the overall revitalization of the districts including �economically, socially, physically, and aesthetically� improving the district and surrounding city (Advisory Council, 1983, p. 75). Historic buildings are being viewed for what they can offer and not for their age and neglect. As William Shopsin challenges, � . . . take a closer look at the ordinary old buildings we have inherited, see beyond their grime and neglect, and discover their great potential for enhancing the contemporary environment� (1986, p. 7). Historic buildings are an important resource and should be treated as such. They should be saved so they can continue to contribute to American society both culturally and economically.

Overall, preservationists want to save the historical and architectural characteristics of historic buildings at any cost. This can often be hard when building codes must be met. This is especially difficult in rehabilitation projects that allow much adaptation to meet current codes and contemporary use needs. The National Park Service, which administers the National Register of Historic Places, has adopted a set of standards and guidelines that should be followed during all rehabilitation projects (Tyler, 2000). These standards, known as �The Secretary of the Interior�s Standards for Rehabilitation,� are very strict about retaining as much historic building material and character as possible. Standard number two, for example, explains what is expected in regards to character: �The historic character of a property shall be retained and preserved. The removal of historic materials or alterations of features and spaces that characterize a property shall be avoided� (U.S. Department of the Interior, 1992, p. 1). These standards are evidence that preservationists believe in keeping historic buildings true to their historic design and characteristics. The historic character and architectural elements must be retained to the greatest extent possible even in adaptive use projects,. These projects are often where the contrasting issues of preservation and accessibility are incompatible. In most cases, in order to create an accessible historic structure some historic character and elements must be sacrificed.

Gathering Information: Accessibility Issues

Since the passage of the ADA in 1990, preservationists have had a very large design challenge to face with regard to deciding how to save historic material and character while making historic buildings accessible. Title III of the ADA requires any new or existing building that houses public accommodations to be designed or modified to allow for accessibility (Swanke Hayden Connell Architects, 2000, p. 79). According to Grant Fondo, author of �Access Reigns Supreme: Title III of the Americans with Disabilities Act and Historic Preservation.�

A private entity is considered a �public accommodation� if it affects commerce and fits into one of the following categories: (a) inn, hotel, or other place of lodging . . . ; (b) a restaurant, bar or other establishments serving food or drink; (c) a . . . place of exhibition or entertainment; (d) a . . . place of public gathering; (e) a . . . sales or rental establishment; (f) a . . . service establishment; (g) a . . . station used for specified public transportation; (h) a . . . place of public display or collection; (i) a � place of recreation; (j) a nursery, elementary, secondary, undergraduate, or postgraduate private school, or other social service center establishment; (k) a day care center, senior citizen center, homeless shelter, food bank, adoption agency, or other social services center or establishment; (l) a . . . place of exercise or recreation. (1994, pp. 104-105)

As this list shows very few buildings are excluded from providing accessibility. Historic buildings are used in a number of the situations listed. In order to help designers create accessible designs within both new and existing buildings, the Americans with Disabilities Act: Accessibility Guidelines for Buildings and Facilities (ADAAG) was created in 1991. These guidelines include all minimal standards that must be met in order to ensure accessibility. Accessibility is now part of all building and safety codes and must be met in all buildings that are considered public accommodations.

With the increase in acceptance of preservation as a viable solution to urban development issues, many historic buildings that do not comply with current building and safety and accessibility codes are considered for museums and many contemporary uses. As stated above, these buildings are required to meet the standards within the ADAAG. David Battaglia, author of Americans with Disabilities Act: Its Impact on Historic Buildings and Structures, explains that any modifications made after January 26, 1992 must comply with the requirements of the ADAAG. Battaglia continues: �Much of the work associated with rehabilitating or restoring historic buildings falls within this definition� (1991, pp. 1172-73). Accessibility must be taken into consideration during the project no matter what the work on a historic building. This is very difficult for preservationists because there is almost always a loss of historic material associated with accommodating for accessibility.

Because most historic buildings were constructed before persons with disabilities were given equal opportunity, there are several aspects of their design that are often the largest problems for accessibility. Marilyn Kaplan, in her booklet Safety, Building Codes and Historic Buildings, identifies the most common barriers to accessibility as �inadequate means of access or egress, inaccessible interior spaces, and inaccessible facilities (toilets, baths, kitchens)� (1996, p. 6). Many historic buildings were originally designed with grand entrances that often included stairs. Stairs are an immense barrier for persons with disabilities. Some of the barriers in the interiors are narrow doorways, stairs, inappropriate room for turning radii for wheelchairs, and narrow hallways. Toilet rooms, kitchens, and other utilitarian spaces of the buildings are often too small for persons with wheelchairs. These deficiencies must all be corrected in order to make the historic building accessible for sharing the building�s past and future with everyone in society.���

Even though some historic significance is almost always stripped away in the process of making historic buildings accessible, these buildings must be made available to everyone. The philosophy of the preservation movement aspires to saving historic buildings to tell the story of America�s past. Preservationists are saving buildings in order to share this historic significance with everyone, including persons with disabilities. Norman Tyler explains, �Having a historic building should not be an excuse for not providing access to disabled persons, and every effort should be made to ensure a rich and satisfying experience for all individuals� (2000, p. 166). Sharing America�s rich historical and architectural past with everyone should be the main objective when saving a historic building.

Outcomes for Resolving Regulatory Conflicts

Because the ideal outcomes of preservation efforts may be jeopardized in order to meet the ADA, a compromise needed to be formed. When the ADA was under consideration by the United States government, the concerns of preservationists were brought to the attention of Congress. As Grant Fondo explains, �Congress recognized these conflicts and attempted a compromise of sorts by creating exceptions to the statutes. This compromise reduced the accessibility requirements for qualified historic properties where modifications would threaten or destroy the historical significance of qualified buildings and facilities� (1994, p. 99). This compromise does not allow historic buildings to be completely exempt from the requirements of the ADA. In fact, if no historical significance is threatened then the building is not considered historical under the ADA and the most stringent requirements for new construction must be met. However, if it can be proven that modifications for accessibility would threaten or destroy historic material and character, the special provisions for accessibility to and within historic buildings can be followed. These provisions still make the building accessible, however, the accessibility is to a lesser degree than for new construction. In The ADA and Privately Owned Historic Facilities, Casey Frank explains what is included in the special provisions: at least one wheelchair-accessible route to the facility�s entrance; at least one accessible public entrance or one accessible separate entrance; one unisex accessible toilet; access to entrance-level public spaces; access to all levels, if practical; and signage at seated level� (1994, p. 2750). These provisions still provide access to historic buildings while helping to maintain as much historical significance as possible. However, some historic buildings, such as museums, cannot meet these standards without losing a majority of their significance. In this case, a third option is available. However, as Norman Tyler warns, the third option should be used only as a last resort when the first two options are not feasible (2000, p. 166). This option allows for providing an alternative experience, such as a virtual tour of and displays from the house museum in an accessible building on the site. Although meeting standards for new construction is always the best approach to accessibility, there are other ways to provide accessibility and save historic significance.

Results in Application: A Case Study

The Zarah Hotel was constructed in 1925 with the hotel lobby, retail spaces, and offices on the first floor adjacent to Main Street and Lakin Avenue in Great Bend, Kansas. The original building appeared from the street side to be a square with nine window bays of eight over one double hung construction on both the Main Street and Lakin facades. During the late 1930s construction started on an addition to the south portion of the building, adding an additional four window bays on the Main Street fa�ade and a fourth floor for hotel employee housing (see floor plans in Appendices A-D). Although the architecture of this building is not grand or really very important to architectural history, the story of the building is important to Great Bend�s history. This building was constructed in a vibrant downtown during a time when Great Bend and central Kansas were experiencing immense economic growth. The increase in hotel space describes how central Kansas and the Great Plains were attracting people from across the country. The city had been in existence for around fifty years and had claimed its worth to the people of central Kansas. The hotel portion of the Zarah building remained in use until the 1970s. The first floor is currently still in use, maintaining retail and office spaces for businesses in downtown Great Bend. However, extensive remodeling was done to the first floor in the late 1970s to accommodate changing design approaches. The exterior facades of the building have retained most of their historic character, which is uncommon for a building in downtown Great Bend. The interiors of the second, third, and fourth floors also retain original design elements, including ceramic tiles, carpeting, and plaster walls. Because of its large scale and proportions, the Zarah Hotel building is an important symbol for the identity of the downtown and the city of Great Bend.

Currently, very little in the Zarah Hotel building is accessible. The ability for persons with disabilities to enter the Zarah Hotel is the first obstacle that must be solved. There are numerous entrances from both the Lakin Avenue and Main Street elevations, however none of them are accessible. Figure One shows one of the main entrances to the lobby of the building. The two main entrances have four risers to the doorway. The entrances to the retail spaces all have one riser to the doorway. Once inside the building, access to the first floor spaces is once again an issue. The lobby space is accessible, however the retail spaces and offices are not accessible (Figure 2). The floor level drops two risers to most of these spaces. Access to the second and third floors is available with an elevator. However, once on the second and third floors, the hotel rooms are inaccessible. The doorways are only 2�-8� rough openings. With the frames added these doorways would not be acceptable according to ADAAG standard 4.2.1, which requires a minimum width of 32 inches at the doorway (1991, p. 14). The bathrooms connected to the hotel rooms also are not accessible. Many of these bathrooms have a one-riser step to gain access to them. As Figure 3 shows, once inside there is not enough room for a wheelchair to turn around. Standard 4.2.3 requires a turning radius of 60 inches to accommodate wheelchair users. Access to the fourth floor is currently not available for persons with disabilities. The historic hardware that is retained on the doors in the building does not comply with the ADAAG standard 4.13.9 (Figure 4). This standard requires �Handles, pulls, latches, locks, and other operating devices on accessible doors shall have a shape that is easy to grasp with one hand and does not require tight grasping, tight pinching, or twisting of the wrist to operate� (1991, p. 37). These are some of the most important accessibility issues that face the Zarah Hotel; still, during a rehabilitation project using this building more accessibility issues may be brought to light. With corrections to these and any other issues that might arise, the Zarah Hotel can once again contribute significantly to its neighborhood and city.

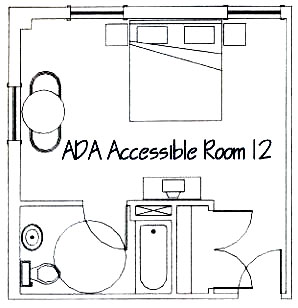

The solutions to the issues of accessibility at the Zarah Hotel must be creative in order to retain historic significance while making the building useful again. In order to retain as much historic material as possible, an accessible door will be placed beside the entrance on Lakin Avenue (Figure 5). Moving the doorway flush with the exterior elevation will modify one of the street entrances to the retail spaces along Lakin. Once inside a ramp will be added to allow wheelchair users to gain access to the first floor. An accessible hallway to the retail spaces should also be provided along the ramp. Because the original interior materials and character on the first floor were lost during the 1970s remodel, adding accessibility to the space will not conflict with the issue of saving historic significance. The solution to the accessibility issues with regards to the hotel rooms and adjacent bathrooms must be addressed as part of a comprehensive rehabilitation project. Because of the period during which the hotel was built, the rooms are all unique in their floor plan and present unique problems. With the number of occupants allowed by the safety codes, the hotel is required to have two accessible sleeping rooms with attached accessible bathrooms. Figure 6 shows the floor plan of these rooms. The new design should retain the original ceramic tiles and doorframes. This will save historic significance while allowing for the hotel rooms to be made accessible. Adding an elevator easily solves access to the fourth floor. The original vertical circulation corridor from the third to fourth floors contains a stairwell and maid�s closets on the second floor (Figure 7). This space easily lends itself to the addition of an elevator. Although the characteristic of the stairwell area between the third and fourth floors will change, it will still be used for vertical circulation (Figure 8). The original door hardware does not comply with ADAAG standards. In order to fix this, new hardware that does comply can be added to the door in place of the existing knobs or thumb levers. Or a lever mechanism can be custom made to retrofit the knobs without losing any historic significance. There are many solutions to achieve accessibility in the Zarah Hotel. Each issue must be considered individually with regard to saving historic significance while making the building economically viable to the community of Great Bend, Kansas.

Conclusion

The historic preservation movement in the United States has been lobbying to save the historically significant buildings throughout the country for several decades. The preservationists want to save as much historic materials and character a possible within these buildings. As can be seen in the analysis of the Zarah Hotel in Great Bend, Kansas, each historic building faces numerous unique accessibility issues. The solutions to those issues are also unique depending upon the historic significance of each building. Some compromise will no doubt have to be taken into consideration with regard to losing historic significance. Saving these buildings and their character is important in making America�s history available to everyone.

References

Advisory Council on Historic Preservation. (1979). The contribution of historic preservation to urban revitalization. Washington, D.C.: U. S. Government Printing Office.

Americans with disabilities act: Accessibility guidelines for buildings and facilities (ADAAG). (1991). Washington, D.C.: U. S. Architectural and Transportation Barriers Compliance Board.

Battaglia, D. H. (1991). Americans with disabilities act: Its impact on historic buildings and structures, Preservation Law Reporter, 10 (11), 1169-79.

Fondo, G. P., (1994). Access reigns supreme: Title III of the Americans with disabilities act and historic preservation, The BYU Journal of Public Law, 9 (1), 99-134.

Frank, C., (1994). The ADA and privately owned historic facilities, The Colorado Lawyer, 23 (12), 2749-52.

Kaplan, M. E. (1996). Safety, building codes and historic buildings. Washington, D.C.: National Trust for Historic Preservation.

Shopshin, W. C. (1986). Restoring Old Buildings for Contemporary Uses. New York: Whitney Library of Design.

Swanke Hayden Connell Architects. (2000). Historic preservation: Project planning & estimating. Kingston, MA: R. S. Means.

Tyler, N. (2000). Historic preservation: An introduction to its history, principles, and practice. New York: W. W. Norton.

U. S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Preservation Assistance Division. (1992). Thesecretary of the interior�s standards for rehabilitation and guidelines for rehabilitating historic buildings, Rev. ed. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior.

Appendix A: First Floor Plan

Appendix B: Second Floor Plan

Appendix C: Third Floor Plan

Appendix D: Fourth Floor Plan

Figure 1. Current main entrance

Figure 2. First floor spaces diagram

Figure 3. Historic bathroom

Figure 4. Historic door opener

Figure 5: First floor accessibility features diagram

Figure 6. Accessible hotel room after rehabilitation

Figure 7: Fourth floor original stairwell (before rehabilitation)

�

Figure 8. Fourth floor with elevator (after rehabilitation)

|

|

|

©2002-2021 All rights reserved by the Undergraduate Research Community. |