Differential Effect of Age with Immigration Status on Junk Food Intake

Kisha Thakur

Thomas Wootton High School, Rockville, MD

Introduction

Obesity has become a major public health policy issue in the United States (Hook, Balistreri, & Baker, 2009). As stated in The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion publication, "OBESITY: Halting the epidemic by making health easier at glance," prevalence of obesity in the last three decades doubled among adults and tripled among children (CDC, 2011). About $147 billion was spent in medical care expenditures for obesity-related conditions in the United States. Moore and colleagues (2009) list a number of studies linking the consumption of junk food to obesity. Targeting obesity-related intervention and prevention efforts to subpopulations at greater risk of junk food consumption will efficiently reduce overall health care costs and health problems in the United States.

Studies suggest that younger Americans consume more junk food than do older Americans (Dave, An, Jeffery, & Ahluwalia, 2009; Bowman & Vinyard, 2004). The immigrant population is the fastest growing segment of the United States' population (Kendal, 2011). Several studies found that younger immigrants tend to integrate faster than do older immigrants into American society. (Hook, Balistreri, & Baker, 2009; Jimenez, 2011; Myers & Pitkin, 2010). Because younger immigrants tend to assimilate faster with their U.S. counterparts than do older immigrants, the question arises whether the consumption of junk food varies with age. This study examines the presence of differential effect of age by immigration status on junk food intake. Past studies exploring the relationship between junk food intake and immigration status by age focused on specific immigrant or age groups but this study will include all immigrants as a single entity.

Method

The study sample was a purposive sample and included individuals ten years of age and older. The data were collected from July 10 until July 24, 2012 at Lakeforest and White Flint Malls, and at Studio X. All subjects were required to sign an informed consent form before participating in the survey. For those aged 17 and younger, their parents were also required to sign the consent form. The survey consisted of four questions:

Please choose one choice for each question listed below:

- Do you think that junk food or food from a fast food restaurant is good for your health?

- Yes

- No

- In past week, how many times did you eat junk food or food at or from a fast food restaurant?

- None

- Only once

- Two to three times

- Four to six times

- Seven or more times

- How old are you?

- Less than or equal to 17 years

- 18 to 34 years

- 35 to 54 years

- 55 to less than 65 years

- 65 years or older

- Where were your parents born?

- Both in U.S.

- None in U.S.

- One in U.S. and other one foreign born

The subjects were told verbally that any fast food restaurant meal and any amount of intake of chips, candy, and soda were considered junk food consumption. To minimize recall bias, the study subjects were asked the number of times they had eaten junk food in the past week. The control group was non-immigrants. Immigrants were defined as individuals whose parents were born in a foreign country, and non-immigrants were defined as those individuals whose parents were born in the United States. Individuals who had one parent born in the United States and the other parent born in a foreign country were excluded from the analysis as past research has questioned the validity of grouping such persons in the above-defined categories (Acevedo-Garcia, Pan, Hee-Hin, Osypuk, & Emmons, 2005; Ramakrishnan, 2004). In addition to dividing the sample population by immigration status, the population was also divided into two different age groups: 17 years and younger, and 18 years and above. The independent variables were immigration status and age of the person. The dependent variable was the consumption of junk food, which was determined by indicating whether the sample person had eaten junk food at least once in the past week or had not eaten any at all. The bivariate associations and regression analysis were performed to determine the presence of a relationship between the dependent and independent variables.

Results

There were a total of 219 (excluding the 30 individuals whose immigration status cannot be determined) sample respondents with valid immigration status, and 64.8 percent (142) of them reported eating junk food at least once in the last 7 days (see Table 1). More than two-fifths of the sample were immigrants (44.3% of the sample or 97 respondents). About 38 percent (83) were 17 years or younger. More than three-fourths of those aged 17 years and younger reported eating junk food at least once in last 7 days. Among 18 years and older, 57.3 percent reported consuming junk food at least once in last 7 days. About 59 percent of immigrants and 55.7 percent of non-immigrants reported having junk food at least once in last 7 days.

Table 1 Descriptive statistics and bivariate associations with junk food intake (N=219)

Sample person

Percent had junk food at least once in last 7 days

(N)

Percent

At least once

Never

Sample person (N)

219

142

77

Sample person (%)

64.8

35.2

Age(***)

17 years and younger

83

37.9

77.1

22.9

18 years and older

136

62.1

57.3

42.7

Immigrant?(**)

Yes

97

44.3

58.8

41.2

No

122

55.7

69.7

30.3

Bivariate analysis results indicate that the relationship between junk food intake and age is statistically significant (p<0.003), but the relationship between junk food intake and immigration status (p<0.093) is not significant at the .05 significance level. A logistic regression model was used to predict the differential effect of age with immigration status on junk food intake. This model predicts the consumption of junk food as a bivariate outcome (1=eaten junk food or at fast-food restaurant at least once in last 7 days versus 0=never eaten junk food or at fast-food restaurant in last 7 days). To explore differential association between junk food intake and age by immigration status, I used a difference-in-difference technique. For that purpose, I created an interaction term between the age and the immigration status. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, North Carolina) and the results are presented in Table 2.

Table 2 Correlates of junk food intake (N=219, chsq=15.7, df=3, p=0.0013)

Had Junk food at least once in last seven days

Age

17 years and below (β1)

1.596***

18 years and above

Reference category

Immigrant?

Yes (β2)

-0.262

No

Reference category

Interaction of age and immigration status

17 years and below, and immigrant (β3)

-1.082*

Intercept (β0)

0.406**

*Significant at 0.15 level, **significant at 0.10 level, and ***significant at 0.05 level

The logistic regression results indicate that the overall model is appropriate and that at least one of the independent variable is statistically related to the junk food consumption in the past week (p<0.0013). Further, the results show that the likelihood of an average 17 year old and younger non-immigrant eating at least once in the last 7 days is higher than that of an average 18 year and older non-immigrant (coefficient for the 17 years and younger age=1.596) and that this relationship is statistically significant at the 0.05 significance level (p<0.002). In this model, the likelihood of an average 18 year and older immigrant eating junk food is less than the non-immigrant counterparts (coefficient for the immigrant status=-0.2624) but this difference is not statistically significant at the 0.05 significance level. The negative coefficient of the interaction term (17 years and below, and immigrant=-1.082) suggests that the differential effect of age with immigration status is negatively correlated with the likelihood of eating at least once in last 7 days but the relationship is not significant (p<0.1103) at 0.05 significance level.

Discussion

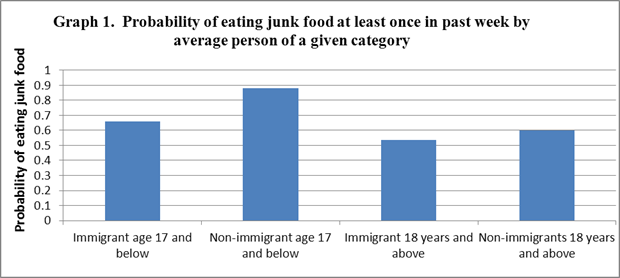

The study results indicate that the differential effect of age with immigration status is negatively correlated with the likelihood of eating at least once in the last 7 days but the relationship is not significant at the 0.05 significance level. To explore the junk food eating variation by age and immigration status, the average probability of eating junk food at least once in last 7 days for each respondent group (e.g. immigrants age 17 years and younger) is presented in Graph 1. It shows that immigrants in each age group are less likely than the respective non-immigrant group to eat junk food in the last 7 days. However, the difference in the likelihood of eating junk food is narrower in the 18 years and older (pnon-immigrant-pimmigrant =0.06) than that of the 17 years and younger age group (pnon-immigrant-pimmigrant =0.22).

Although the results cannot be generalized to the entire United States population, the finding adds to the current literature regarding the junk food eating behaviors prevalent among United States' subpopulations. This finding suggests that, overall, the younger an American individual is, regardless of whether he or she is an immigrant, the more likely to consume more junk food than that of his or her older counterparts and that the average immigrant in each age group consumes less junk food than the average non-immigrant. Perhaps, efforts toward the reduction of junk food intake should be more focused on the younger U.S. population.There are two further questions or experiments that can be considered. First, the sample size was small which is why the age groups were broken into two separate categories. Further studies should be conducted to pinpoint if there is a specific age group or range for focus in order to prevent obesity. Second, all immigrants were grouped into one group and all non-immigrants into another group, but further studies can focus on discrete racial groups to see if there is a relationship between junk food intake and age in each immigrant and non-immigrant racial/ethnic group.

References

Acevedo-Garcia, D., Pan, J., Hee-Jin, J., Osypuk, T. L., & Emmons, K. M. (2005). The effect of immigrant generation on smoking. Social Science & Medicine, 61(6), 1223-1242.

Bowman, S. A., & Vinyard, B.T. (April 2004). Fast Food Consumption of U.S. Adults: Impact on Energy and Nutrient Intakes and Overweight Status. Journal of American College of Nutrition. 23(2), 163-168.

CDC. (2011). OBESITY: Halting the epidemic by making health easier at glance. Retrieved on January 14, 2013 from http://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/resources/publications/aag/pdf/2011/Obesity_AAG_WEB_508.pdf

Dave, J. M., An, L. C., Jeffery, R. W., & Ahluwalia, J. S. (2009). Relationship of Attitudes Toward Fast Food and Frequency of Fast-food Intake in Adults. Obesity, 17(6), 1164–1170.

Hook, J. V., Balistreri, K. S., & Baker E. (2009, September). Moving to the Land of Milk and Cookies: Obesity among the Children of Immigrants. Migration Policy Institute. Retrieved from http://www.migrationinformation.org/feature/display.cfm?ID=739

Jiménez, T. R. 2011. Immigrants in the United States: How Well Are They Integrating into Society? Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute.

Kendal, W. A. (2011, January). The U.S. Foreign-born population: Trends and Selected Characteristics. Congressional Research Service Reports for the Congress. Retrieved from http://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R41592.pdf

Moore, L. V., Diez Roux, A. V., Nettleton, J. A., Jacobs, D. R., & Franco, M., (2009). Fast-Food Consumption, Diet Quality, and Neighborhood Exposure to Fast Food. American Journal of Epidemiology, 170(1), 29-36.

Myers, D. and Pitkin, J. (September 2010). Assimilation Today: New Evidence Shows the Latest Immigrant to America Are Following in Our History's Footsteps. Washington, DC: Center For American Progress. Retrieved on January 5, 2013 from http://www.americanprogress.org/wp-content/uploads/issues/2010/09/pdf/immigrant_assimilation.pdf

Ramakrishnan, S. K. (2004). Second-Generation Immigrants? The "2.5 Generation" in the United States. Social Science Quarterly, 85(2), 380-399.

|