Dating, Assertiveness, and Misconceptions of Assertion

Andrew

Scherbarth

University of Nebraska-Lincoln

Abstract

This empirical study examines dating competency and status in relation to assertiveness; the interplay between assertiveness and assertion of autonomy as well as aggression are discussed. Ninety-six University of Nebraska students, of average age 21 and in their third year of college, completed a demographic questionnaire and battery of surveys. Results indicate neither dating status nor gender are predictors of assertiveness, which in turn is not always associated with aggression or argumentativeness.

Introduction

Dating is a ritual essential to the development of romantic relationships in the context of Occidental culture. Numerous studies have linked assertiveness with dating competency and prosocial behaviors. This study seeks to find interrelationships between dating and assertion among midwestern college students, as well as to clarify possible misconceptions of assertiveness.

Lesure-Lester (2001) conducted research with 217 college students representing Asian, Mexican, African, Caucasian, and Multiracial students of both sexes on two different college campuses. Significant correlations were revealed using the Dating and Assertion Questionnaire (DAQ), the Social Avoidance and Distress Scale (SAD), and the Social Anxiety Thoughts Questionnaire (SAT). Among the correlations identified was a positive relationship between dating competence and assertiveness (r=.60, p<.001).

Flora and Segrin (1999) published a complementary study evaluating the interplay between social skills and close relationships satisfaction for 131 couples�half dating and half married. Results found a strong positive correlation between a male�s conflict management skills and female relationship satisfaction. A positive relationship was also found between emotional support skills and personal satisfaction. Therefore, each of these skills are both prosocial and assertive in nature, and are directly related to relationship satisfaction�one to personal and the other to partner satisfaction.

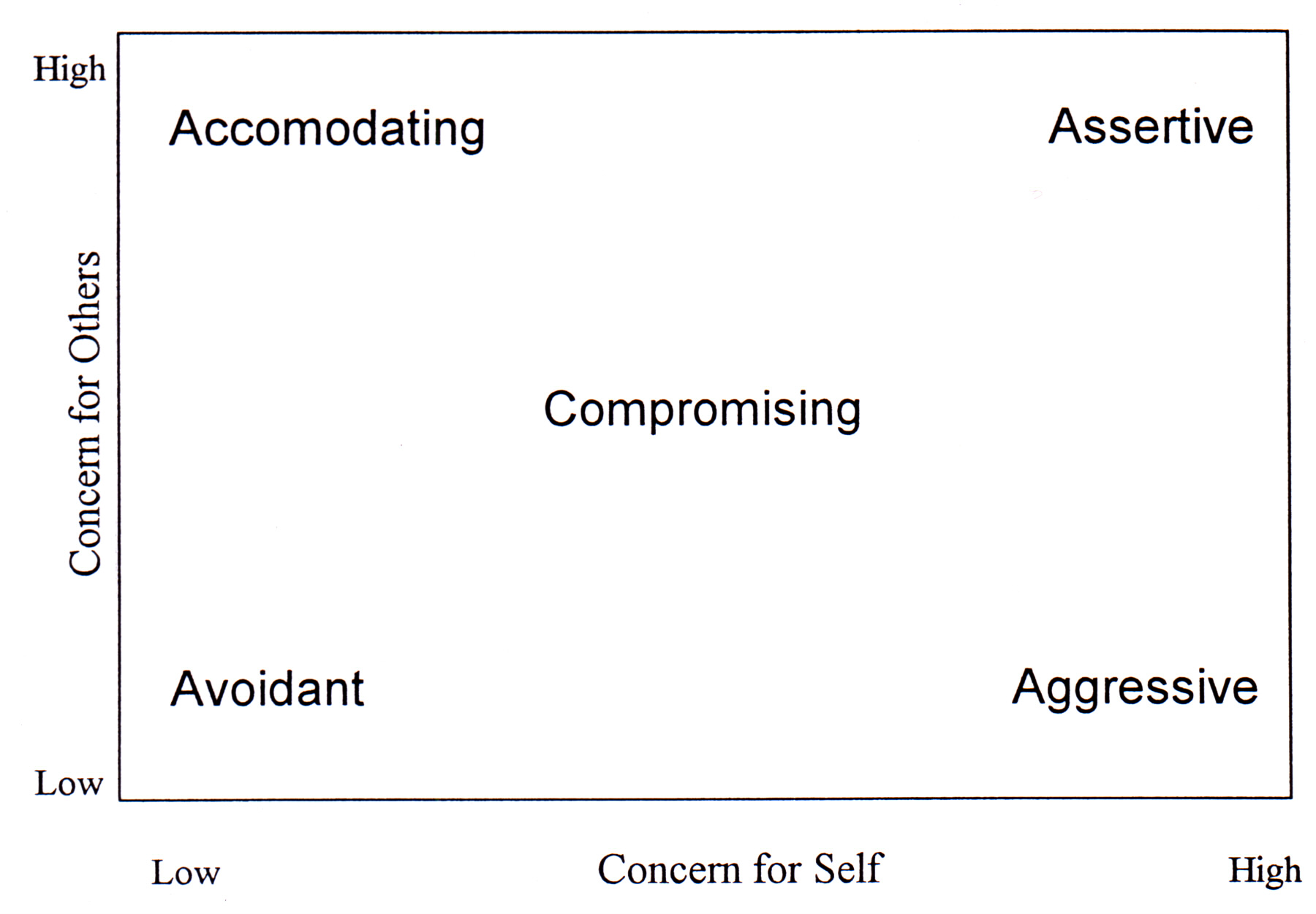

Assertiveness is a concept often confused with aggression. It is only by virtue of presentation and circumstance that assertive behaviors may be considered aggressive in nature. Thomas & Kilmann�s Model of Conflictual Styles, (see Figure 1) illustrates the difference. Their model places conflict management styles on two axiom: "Concern for Others" and "Concern for Self." Although both the assertive and aggressive styles are high on the axis of concern for oneself, the assertive style also places high on the axis of concern for others. Thus, aggressive action shows a lack of concern for others, leading to a variety of consequences (Wilmot & Hocker, 2001).

A study by Swanson (1999) differentiates assertive and aggressive communication patterns. A series of three real-life scenarios were described, including customer service. Swanson found people who scored high as aggressive were much less likely to give recommendations (especially positive ones) to their friends than were those scored as either assertive or unassertive on a battery of psychological inventories.

Further elaboration of differences between assertiveness and aggression may be found in a study by Weitlauf, Smith, & Cervone (2000). The team measured a slew of personal characteristics and interaction styles for 80 female college dorm residents, in the months before, during, and after a 12 hour, multisession self-defense course. Training did not include traditional eastern philosophies but rather mastery of basic self-defense technique, along with verbal resistance, emotional, and relaxation training in a program developed by Weitlauf et al. and available to the public. Results found women were significantly more assertive and felt able to effectively defend themselves, in addition to having a drastic reduction in hostility following training.

The first two studies tie normal and healthy dating behaviors with assertiveness. Both seek to identify aspects of a college student�s functional abilities that contribute to either success or distress in dating. The latter two studies show a distinction between assertive and aggressive behavior. This study searches for similar results among never married, Nebraska college students and provides another platform to dispel misconceptions regarding assertive behavior.

The following hypotheses attempt to shed light on the issue of assertiveness as it applies to courtship among Nebraska college students. (a) It is believed dating competency requires assertiveness; thus there will be a negative linear relationship in a correlational analysis. (b) Again, because it is believed dating college students are more assertive than those who do not date, an ANOVA will reveal a lower mean assertiveness score among daters (indicating more assertiveness). (c) Gender is not thought to be a factor in the analyses, thus no significant difference between male and female assertiveness scores is expected.

The next set of hypotheses attempt to dispel erroneous ideas of assertiveness: (a) It is thought being assertive does not always indicate one acts without regard to the needs and desires of others; thus, a negative correlation is predicted between assertiveness and assertiveness of autonomy (i.e. expression of the desire to act independently). (b) Dating competency is expected to be reduced with greater assertion of autonomy; thus, there should be a negative linear relationship. (c) Assertiveness and argumentativeness are not believed to be synonymous; thus, a positive or no linear relationship is predicted between scores among these college-aged, Nebraska residents.

Method

Participants

Data were collected from 102 Nebraska students, who were on average in their Junior year at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. There were 42 males and 60 females surveyed; 96 were never married.

Instruments

A packet of six inventories was distributed to each participant. However, only data found by four inventories were used for these analyses. Each packet contained nine pages, beginning with a statement of informed consent followed by a and demographic data questionnaire (age, gender, currently dating, number of siblings, etc.)

The Argumentativeness Scale (ARG) is a twenty-question survey, which compares the difference between tendencies to approach argumentative situations against tendencies to avoid argumentative situations. Statements such as, �Arguing over controversial issues improves my intelligence,� and �I get an unpleasant feeling when I realize I am about to get into an argument,� are evaluated on a five-point-scale of frequency from never to almost always true (Infante & Rancer, 1982). Higher scores indicate willingness and enjoyment of arguments.

The Dating and Assertion Questionnaire (DAQ) is a nine-question survey, which identifies appropriate dating behaviors and assertiveness. Statements such as, �Maintain a long conversation with member of the opposite sex,� and �Assume a role of leadership,� are evaluated on a four-point frequency scale (Levenson & Gottman, 1978). Higher scores indicate more dating competency.

The Interpersonal Dependency Inventory is a forty-eight question survey, which identifies lack of self-confidence, emotional reliance on others, and assertion of autonomy. Statements such as, �In an argument, I give in easily,� �I would rather be a follower than a leader,� and �I only rely on myself� are evaluated on a four-point scale. Higher scores indicate more intense feelings regarding each scale (Hirschfield, 1977).

The Bakker Assertiveness-Aggressiveness Inventory (AS-AGI) is a thirty-six-question survey, which identifies assertiveness and aggressiveness. Statements such as �Someone has, in your opinion, treated you unfairly. You confront them about this,� and �You see an opportunity to get ahead but know it will take a great deal of energy. You take the opportunity and forge ahead,� are evaluated by the participant on a five-point frequency scale. Lower scores on either subscale indicate a higher degree of assertiveness or agressiveness (Bakker, Mbakker-Rabdau, & Brett, 1978).

Procedure

Students in the Psychology Research Methods 350 Lab were each given six surveys. Each person completed one then individually asked other university students to complete the rest of the surveys. At times, coworkers and friends were selected by researchers; at others, total strangers received surveys. No special instructions were given to participants.

Students individually tallied scores for each inventory. One week later, students put their data into a SPSS statistical program database. One hundred and two students had participated. Analyses were completed after removing the six who were married and the one participant who did not complete the AS-AGI.

Results

Table 1 indicates that the college students were on average 21 and were in their third year in college. Mean scores on all pertinent scales are listed. There was a borderline significant linear relationship found for dating competence and assertiveness (r=-.20, p=.053).

Table 2 displays that there is no mean difference between the assertiveness scores between students who are dating (M=42.3, S=14.19) and those who are not currently dating (M=45.4, S=13.6), F=1.14, p=.289, MSe=193.71. These results are contrary to the hypothesis that Nebraska college students who are currently dating are more assertive than those students who are not.

Table 1 - Summaries of Age, Years of College, Assertiveness, Autonomy, Dating Competence

Variable Univariate Summary

M S N

Age 21.27 2.95 96

Year in College 2.87 1.19 94

Assertiveness 43.89 13.92 95

Assertiveness of Autonomy 27.10 6.23 96

Dating Competence 13.95 3.19 96

Table 2 - Mean Assertiveness Scores for Dating Status (N=95)

Dating Status M S n

Currently Dating 42.33 14.19 46

Not Dating 45.37 13.63 49

Table 3 - Mean Assertiveness Scores for Gender Status (N=95)

Gender M S n

Male 42.79 13.34 39

Female 44.66 14.37 56

Figure 1. Thomas & Kilmann's Conflict Management Style Model

As shown in Table 3, there was no mean difference between assertiveness scores among males and females, F=.411, p=.523, MSe=194.8. These data support the hypothesis of no difference in assertiveness scores on the basis of gender.

A significantly negative correlation between assertiveness and assertion of autonomywas found (r=-.43, p<.001). Results are consistent with the hypothesis that an increase in assertion of autonomywill be tied to an increase in assertiveness.

No significant correlation between dating competence and assertion of autonomy (r=.06, p=.60), inconsistent with the hypothesis stating there would be a significant negative relationship between these variables, indicating as more autonomy sought the lower the dating competence.

Finally, no significant linear relationship was found between argumentativeness and assertiveness, (r= -.13, p=.21). Hence, the hypothesis that a positive relationship or no relationship exists between argumentativeness and assertivenesswas supported.

Discussion

The research hypotheses regarding assertiveness in relation to dating produced mixed results. Assertiveness scores were not vastly different between those who were or were not dating. A borderline significant linear relationship between dating competency and assertiveness existed; significance standards were missed by a mere one-third percent margin, as p=.053. Despite these results, an ANOVA indicated students of either gender were equally assertive.

Research hypotheses regarding multiple views of assertiveness also had mixed results. No correlation was found between assertiveness and argumentativeness, showing that being assertive and enjoying/having tendencies to argue, are not always interrelated.

Furthermore, assertion of autonomy was significantly correlated with more assertiveness; however, no correlation between dating competency and assertion of autonomy was found, contrary to the hypothesis. The latter set of hypotheses were established to show that although a correlation exists between assertiveness and assertion of autonomy, the two are still not synonymous. No correlation was found, so autonomy seeking behaviors were not linked to dating competencein any way, indicating some relationships require more autonomy than others.

Although this study did not find all of the hypothesized effects, it was certainly not a waste. One explanation lies within the nature of the hypothesis stating those who were dating would be more assertive than those who were not. It was believed that those who were not dating were not assertive enough to maintain a relationship. The results show that this appears not to be the case at UNL. A possible explanation may be participants who were not dating may be quite assertive�perhaps they just choose to assert their desire to be autonomous or desire to complete coursework, rather than interacting with others. Neither case promotes the maintenance of relationships in general, let alone intimate relationships.

Further explanation deals with the power of this study. A glance at Friedman�s Partial Power Table (1982, as cited by Garbin, 2001) shows an effect of r=.25 and .80 probability of finding this effect, needs a sample of a least 120 people. An effect of r=.30 and .80 power, on the other hand, only requires 82. This particular analysis included 95 participants. The probability of making a Type II error is 30-40% for an effect size between r=.25 and .30.

Researchers may use these findings to design a more accurate, concise study. To improve accuracy of measurement, other scales may be utilized. One may choose to narrow the battery of surveys in each packet to ensure participant fatigue does not confound data. (The large number of scales in each packet was advantageous for the research team, as it allowed each of the 16 researchers freedom to formulate unique hypotheses independently of others, yet the number of surveys became wearisome for a few participants.) A study administered in a standardized setting to more students may also increase the validity of potential results.

Exploring reasons why some students are not dating is a worthwhile venture. It is quite possible a few of these students may be distressed about their social skills and/or dating status. Besides just looking at assertiveness as a main factor in why a student may not be dating, the desire to date may be explored. Additionally, credit hours taken, major, professional goals, language usage, number of children, and family of origin interaction style may also play a role in a student�s dating status. It is plausible that University of Nebraska students who are highly career-motivated do not date. Questionnaires addressing these demographics, frankly asking why they may not be dating as well as providing inventories addressing loneliness and interaction style could potentially add additional insight.

Dating is one of the most common activities in not only the U.S., but also in other countries worldwide. Dating status and dating has been linked to assertiveness in numerous studies, although assertiveness is found in various forms, reflected by the multitude of paths a person may take. Study of this issue may help those who desire another lifestyle, another path less beaten and more pleasant.

References

Bakker, C. B., Nbakker-Rabdau, M. K., & Brett, S. (1978). The measurement of assertiveness and aggressiveness. Journal of personality Assessment, 42, 277-284.

Flora, J., & Segrin, C. (1999). Social skills are associated with satisfaction in close relationships. Psychological Reports, 84, 803-804.

Friedman. (2001). Partial power table. In C. Garbin, Presentation: Effect size and power analyses for multiple group designs. University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Psychology 350 Research Methods Materials, 1, Unit 3, p. 2

Hirschfield, R. M. A., Kierman, G. L., Gough, H. S., Barret, J., Korchin, S. J., & Chodoff, P. (1977). A measure of interpersonal orientation: The liking people Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 41, 610-618.

Infante, D. A., & Rancer, A. S. (1983). A conceptualization and measure of argumentativeness. Journal of Personality Assessment,46, 72-80.

Lesure-Lester, G. E. (2001). Dating competence, social assertion and social anxiety among college students. College Student Journal, 35, 317-321.

Levenson, R. W., & Gottman, J. M. (1978). Toward the assessment of social competence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 46, 453-463.

Swanson, S. R. (1999). Reexamination of assertiveness and aggressiveness as potential mediators of verbal behavior. Psychological Reports, 84 (3), 1111-1114.

Weitlauf, J. C., Smith, R. E., & Cervone, D. (2000). Generalization effects of coping skills training: Influence of self-defense training on female efficacy beliefs, assertiveness and aggression. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, (4), 625-633.

Wilmot, & Hocker. (2001). Thomas & Kilmann�s Model of Conflictual Styles. Interpersonal Conflict (6th ed., Chapter 5). New York: McGraw-Hill.

|

|

|

©2002-2021 All rights reserved by the Undergraduate Research Community. |