Russian Demographics:

The Role of the Collapse of the Soviet Union

Christopher Hoeppler

McMaster University

Abstract

Communism is a political ideal that is often viewed negatively by democratic societies. Since the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, the Russian Federation has experienced a rising mortality rate. It is clear that the political turmoil of the country played a key role in the eventual demographics of Russia. Coinciding with the onset of democracy a number of factors including economics, lifestye, healthcare, and disease incidence have contributed to the decline in population. The current demographic state, underlying causes, and next steps will be explored within the paper

Introduction

The Russian Federation experienced a surge in death rates of almost 40 percent since 1992, with numbers rising from 11 to 15.5 per thousand (Bhattacharya et al., 2011). The fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 brought with it many social, political, and economic changes that continue to affect Russia to this day. Although all countries progress along the demographic transition model differently, general trends are shown. Nonetheless, Russia appears to be experiencing a unique transition of its own. Each country experiences population decline for varying reasons, such as disease diffusion as experienced by Africa with the AIDS epidemic; others can be caused by societal advancements that lead to lower fertility rates. Population decline was evident in Russia since the fall of the Soviet Union, which is why it serves as an interesting case study. On the surface it is counterintuitive that the state of the country would worsen after the fall of the communist party; however it is likely that political turmoil was responsible for the onset of the demographic problem in Russia. A number of factors including economic, lifestyle, health care, and disease incidence have contributed to Russia’s decrease in population. The following discussion will assess Russia’s current demographic state, identify the underlying causes, and suggest logical next steps for Russia.

The Soviet Union

The Soviet Union refers to the joining of a number of different republics under common rule. Communism was the former political system that governed these joined regions and maintained rule from 1985-1991 (Barr & Field, 1996). Gorbachev, the leader of the Communist party, imposed Glasnost, a new policy that forced political openness. As a result, the negative aspects of life under Soviet rule were exposed, such as poor housing, alcoholism, and poor technology. In light of this negative exposure, the Soviet government as well as the Communist party lost influence over its population due to reduced trust (Matlock, 1995). Gorbachev also introduced perestroika, or economic restructuring, which was not well received by the public (Stoner-Weiss & McFaul, 2009). A number of factors contributed to the eventual demise of the Soviet Union that began with the separation of Poland, and a domino effect of states leaving the union continued (Stoner-Weiss & McFaul, 2009). A combination of ethnic tension between the Soviet republics as well as growing interest in independence led to the eventual dissolution of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s (Anderson, 2002).

Due its large landscape of natural resources, such as timber and oil, the Russian Federation was a key player in the global economy (Grigoriev, 2005). The decisions that took place within its borders had an impact on other regions of the world, such as creating a flux in oil prices (Grigoriev, 2005). Ever since the fall of the Soviet Union, the population of Russia has been on a steady decline (Anderson, 2002). The demographics of Russia continue to be one of the most pressing issues facing the country; former president Putin even placed dealing with it as a top priority (BBC, 2000).

Russia’s Current Demographic State

The aging population of Russia outnumbers its working class due to population decline (Nikitina, 2000). Russia’s total fertility rate prior to 1991 generally fluctuated around the replacement level and remained well above it during the 1980s (Anderson, 2002). The Soviet Union’s government exercised a pro-natalist stance and offered incentives for larger family sizes, which can help to explain why populations appear to make a dramatic decrease after this government structure collapsed (Anderson, 2002). The breaking up of the Soviet Union brought with it economic hardships that influenced the fertility rate of the nation by creating unfavourable conditions to bear a child (Kharkova & Andreev, 2000). The GNP of Russia decreased by nearly one-half in 1995; when combined with the relatively high cost of birthing and caring for a child, it is clear that the declining fertility rate was a result of economic conditions (Ranjan, 1999).

Russia’s life expectancy in 2009 for men and women was 60 and 73 respectively, well below other European countries’ averages that were as high as 77 in countries such as Germany (Wong, 2009). Ironically, life expectancy was lower under the Russian Federation than it was under a communist regime (roughly 58 for women and 64 for men) (Notzon et al., 1998). These low numbers were attributed to a high level of mortality among working class men as a result of lifestyle choices, including alcoholism and smoking (Wong, 2009). About half of all deaths of working age men could be related to hazardous binge drinking (Leon, 2007). Such lifestyle choices are commonly associated with depression, a growing problem within Russia post Soviet times (Griffiths, 2005). The most frequent cause of death in Russia was heart disease, which accounted for 56.7 percent of all deaths (RIANavosti, 2007)

The poor state of the health care system was one of the leading forces affecting Russia in the past decade. Barr and Field (1996) found the post-Soviet health care reform increased costs and limited access to health care, which likely affected Russia’s life expectancy. It was not until Putin was elected as president in 2000 that major reforms to the health care system took place (Marquez, 2008). A poor health care system also affects the quality of disease treatment and prevention. The HIV/AIDS epidemic is an issue plaguing Russia’s youth; people aged between 15 and 29 make up 80 percent of infected persons. The rapid spread of HIV/AIDS has been attributed to the massive amount of intravenous drug users now present within the country (The World Bank, 2011).

Health Care

Under Soviet governance, the health care system was socialized, and citizens were guaranteed full health protection without charge. In the 1980s, there existed easily accessible clinics and first aid facilities for public use (Curtis, 1996). The Soviet Union was also the first country to have an equal ratio of hospital beds to citizens (Curtis, 1996). Despite the accessible nature of the Soviet health care system, there still existed some inconsistencies amongst rural and urban areas as well as severe need for advancements in practices and technologies (Curtis, 1996). Although there was equal access to the health care system, Soviet facilities lacked essentials. As a matter of fact, in 1990, 24 percent of hospitals did not have adequate plumbing, 19 percent lacked central heat, 45 percent lacked bathrooms or showers, 49 percent had no hot water, and 15 percent operated without any water at all (Cassileth et al., 1995).

After the fall of the Soviet Union, the already lacking health care system saw no improvements and began to deteriorate exponentially (Notzon et al., 1998). Poor medical care combined with high pollution from vehicles and factories as well as dwindling resources lowered the health status of the people (Cassileth et al, 1995). The health care system in Russia was in a crisis as a many practicing doctors were under trained, lacked updated medical equipment, and were poorly paid. Ultimately this led to a shortage of doctors, with the ratio dropping to one for every 275 citizens (Curtis, 1996).

The distaste for the health care system was rooted in the underperformance of two components of the system: polyclinics and hospitals (Brown & Rusinova, 1997). A polyclinic is a place that offers a wide range of health care services. The medical system has produced a population of patients who “refuse hospital admission, decline needed surgery, and only seek medical care after their disease has progressed to advanced stages” (Petrov & Vovin, 1993).

The transition to a market system of health care was difficult on those accustomed to Soviet-era practices (Brown & Rusinova, 1997). Accessibility to health care resources decreased since free coverage was lost. It was common practice for charges and fees to be applied for medical assistance, a luxury that many low-income families cannot afford (Brown & Rusinova, 1997).

Economy

There were two significant economic crises that riveted Russia in the 1990s; the first occurred in 1992, and the second in 1998. The first coincided with the transition to a market economy following the fall of communism. The second crisis involved the crash of the banking system (Gavrilova et al, 2001). Part of this transition was the removal of price controls leading to a rise in consumer prices of up to 140 percent, without a subsequent raise in living wages (Gavrilova et al, 2001; Kohler & Kohler, 2002). The loss of controlled wages and incentives to maximize employment paved the way to lowered levels of output and productivity; this caused a decrease in productivity of the labour market that led to increased poverty and inequality. A difference in earnings was exacerbated by this effect, placing much of the population in poverty (Klugman & Braithwaite, 1998).

The second economic crisis was characterized by increased violence and a sharp increase in infectious disease-related mortality (Gavilova, 2001). Reduced demand for labour meant increased layoffs and unemployment. Coinciding with this was a decrease in overall income amongst Russian families. The number of poor households, with 35 percent living below the official poverty line by 1995, rose shortly after the transition to democracy (Klugman & Braithwaite, 1998). The concentration of households experiencing poverty was most prevalent in ones with children and unemployed individuals (Klugman & Braithwaite, 1998).

Poverty had negative implications on population growth by inducing behavioural changes within the population. The process of having a child, and subsequently nurturing and raising it, was seen as an economic burden during trying times. When there is concern regarding job security and unemployment, the likelihood of reproduction is often reduced to reflect the unwanted burden associated with children (Kohler & Kohler, 2002). The drop in total fertility in the Russian Federation, by almost 35 percent, solidified the positive correlation between poverty and lowered fertility.

Suicide

The World Health Organization (WHO) found that suicide rates were on the rise globally; however Russia had one of the highest suicide rates of all with 38 per 1000 people (WHO, 2007). The fall of the Soviet Union brought with it political unrest, economic turmoil, as well as increased stress on the population. With a number of people turning to narcotics and alcohol to ease the pain, others took their lives as a last ditch effort to escape. WHO found that people commit suicide when they feel there is no other solution, whether it is financial or personal problems (WHO, 2007). These feelings were in existence amongst the Russian population, and they were exacerbated by the transition to a market economy. The rates of suicide can be associated with a number of other factors that affect the demography of Russia, e.g., alcoholism and job loss, are discussed herein.

Alcoholism

Russia ranks amongst the world’s heaviest drinking countries (Vancouver Sun, 2011). Prior to Soviet rule, alcohol consumption was steadily on the rise, with most consumption in the form of binge drinking (McKee, 1999). Binge drinking leads to an increase in deaths related to alcohol consumption, e.g., accidents, violence, and alcohol poisoning (Chenet et al, 1998). Alcohol played a key role in the mortality crisis experienced during the 1990s, especially a spike in alcohol-related deaths in working age males (Pridemore, 2002).

The Gorbachev anti-alcohol campaign was set in motion to reduce alcoholism in Russia and was in place from 1985-1988 (Bhattacharya, 2011). Under the Gorbachev policy, states were poised to develop strategies to reduce alcohol consumption levels, including banning of alcohol in some regions, raising prices, and reducing outlets for alcohol consumption (Mckee, 1999). During its run, alcoholism declined significantly, and the crude death rate fell by nearly 12 percent (Mckee, 1999). A reduction of alcohol-related deaths lowered mortality levels, suggesting the program had positive impacts. Unfortunately, the Gorbachev campaign officially ended in 1988 due to its unpopularity and loss of alcohol related revenue (Bhattacharya, 2011).

The Russian Federation did not reach pre-Gorbachev levels of alcoholism until the early 1990s, around the time of the dissolution of the Soviet Union, with economic hardships and depression stated as the reasons behind it. Subsequently, the death rate also climbed following the removal of the Gorbachev policy (Bhattacharya, 2011). Furthermore, alcoholism was associated with a number of adverse health risks, in particular an increased risk of cardiovascular related problems (Chenet et al, 1998). As mentioned, cardiovascular disease remained one of the leading causes of death and must be addressed to reverse population decline (RiaNovosti, 2007).

HIV/AIDS

The first documented case of HIV/AIDS was documented in 1986; however it was not expected to become a widespread health crisis. It was the lack of overlap between government practices and reality that powered the spread of HIV (Feshback, 2005). In 1987, the diffusion of AIDS was positively viewed under the notion it could eventually lead to the demise of drug dealers and prostitutes (Feshback, 2005). Meanwhile, government officials denounced the existence of HIV and related social problems within the Soviet Union (Feshback, 2005).

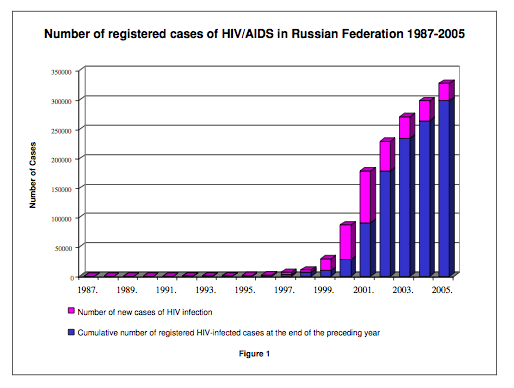

After the fall of the Soviet Union, the newly independent Russian Federation shifted its focus to other political issues, and the once small issue of HIV/AIDS fell to the wayside. According to the United Nations Program on HIV/AIDs (UNAIDS), approximately 1.1 percent of the Russian population, or 860,000 Russians, lived with HIV or AIDS (UNAIDS, 2005). Since 1995, Russia experienced an exponential increase in HIV/AIDS cases with the number of registered cases of HIV/AIDS reaching over 300,000 in 2005 as seen in Figure 1. The diffusion of AIDS throughout the country was attributed to an increase in intravenous drug use with over 90 percent of registered HIV infections linked to it in the year 2000 (Holachek, 2006). Other affected populations included street children, sex workers, prisoners, and children born to affected women (Roberts, 2010).

Figure 1. Number of Registered Cases of HIV/AIDS in Russian Federation 1987-2005

Source: Holachek C. (2006). Russia’s shrinking population and the Russian military’s HIV/AIDS problem.Infected families have a lowered life expectancy and children born with the disease are prone to increased morbidity (Rigbey, 2009). The increase in drug use, fueled by the illegal drug trade, was one of the pressing issues facing Russian law enforcement. Deaths, related to overdose and drug related complications, added to the already deteriorating demographics of Russia. Nearly 65 percent of newly detected HIV cases were linked to intravenous drug use (Rigbey, 2009). The population of Russia was affected by the HIV/AIDS epidemic by adding to mortality and morbidity numbers (Holochek, 2006). If Russia hopes to avoid the turmoil experienced by other AIDS-ridden regions such as Africa, steps must be taken to avoid a larger backlash in the future.

Next Steps and Conclusion

Russia also plays an important role in international politics. Exploring the reasons behind its declining population could affect its role in the world and could result in changes in its relationship with North America. Russia’s depopulation continues to be a great concern, because it will be difficult to sustain the elderly population if it greatly outnumbers its workforce. It is important for Russia to deal with the demographic imbalance properly to avoid a larger catastrophe in the near future. After a wave of policies and incentives, Russia’s population experienced its first increase in 2009 after over a decade of decline (RIANovosti, 2010). The onset of this reversal suggests the policies put in place are having some effect on the status of the population. The prevalence of alcoholism needs to be addressed, and more policies must be put in place to reduce alcohol consumption. Although steps are being taken to deal with the ongoing HIV/AIDS epidemic, more needs to be done to ensure these policies are implemented properly and proper procedures are being followed. In terms of the economy, Russia needs to impose an economic restructuring plan that addresses key holes in it’s workforce that need to be filled and find ways to create meaningful and long-term employment for it’s citizens. Nonetheless the future of Russia is very much up in the air, and time can only tell what the future holds.

References

Anderson, B. (2002). Russia faces depopulation? Dynamics of population decline. Population and environment. 23 (5). 437-464

Barr, D., & Field, M. (1996). The current state of health care in the former soviet union: Implications for health care policy and reform. American Journal of Public Health. 86(3).

BBC News. (2000). Russian population in steep decline. Retrieved from: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/988723.stm

Bhattacharya, J., Gathmann, C., & Miller, G. (2011). The Gorbachev Anti-Alcohol Campaign and Russia’s Mortality Crisis.

Brown, J., & Rusinova, N. (1997). Russian meidcal care int he 1990s: A user’s perspective. Soc. Sci. Med 45 (8): 1265-1276.

Cassileth, B., Vlassov, V., & Chapman, C. (1995). Health care, emdical practice and medical ethics in Russia today. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 273 (20): 1568-1573.Chenet, L., McKee, M., Leon, D., Shkolnikov, V., & Vassin, S. (1998). Alcohol and cardiovascular mortality in Moscow; new evidence of a causal association. Journal of Epidemiology Community Heath. 52: 772-774.

Curtis, G. (1996) Russia: A country study. Washington: GPO for the library of congress.

Feshback, M. (2005). The early days of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the former Soviet Union.

Gavrilova, N., & Evdokushkina, G., Semyonova, V., & Gavrilov, L. (2001). Economic crises, stress and mortality in Russia. Paper presented at The Population Association of American 2001Annual Meeting.

Griffiths, A. (2005). Handbook of Federal Countries. (pp. 263-279). Quebec: Library and Archives Canada.

Grigoriev, L. (2005). Russia’s place in the global economy. Russia in global affairs. Retrieve from: http://eng.globalaffairs.ru/number/n_4959

Holachek, C. (2006). Russia’s shrinking population and the Russian military’s HIV/AIDS problem. For the Atlantic Council of the United States.

Kharkova, T., & Andreev, E. (2000). Did the ecnomic crisis cause the fertility decline in Russia: Evidence from the 1994 microcensus. European Journal of Population. 16: 211-233.

Kohler, H., & Kohler, I. (2002). Fertility decline in Russia in the early and mid 1990s: The role of economic uncertainty and labour market crises. European Journal of Population. 18: 233-262.

Klugman, J., & Braithwaite, J. (1998). Poverty in Russia during the transition: an overview. The World Bank Research Observer. 13, 37-58.

Leon, D., Saburova, L., Tomkins, S., Andreev, E., Kiryanov, N., McKee, M., & Shkolnikov, V. (2007). Hazardous alcohol drinking and premature mortality in Russia: population based case-control study. The Lancet, 369(9578), 2001-2009.

Marquez, P. (2008). Public spending for Russia for Health Care: Issues and options. Retrieved from: http://siteresources.worldbank.org/... on January 25, 2011

Matlock, J. (1995). Autopsy of an empire: The american ambassadors account of the collapse. Random house.

McKee, M. (1999). Alcohol in Russia. Oxford Journals; Alchohol and Alcoholism. 34; 824-829

Nikitina, S. (2000). Expert group meeting on policy responses to populatin ageing and population decline. Department of Economic and Social Affairs.

Notzon, F., Komarov, M., Ermakov, S., Sempos C., Marks, J., & Sempos, E. (1998). Causes of declining life expectancy in Russia. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 279(10):793-800.

Petrov, M., & Vovin, N. (1993). Analysis of cases of late application for medical care and refusal of hospitalization. Sov Zdravokhr. 1989; 10: 30-32

Pridemore, W. (2002). Vodka and violence: alcohol consumption and homicide rates in Russia. American Journal of Public Health. 92 (12): 1921-1930.

Ranjan, P. (1999). Fertility behaviour under income uncertainty . European Journal of Population, 15(1), 25-43.

RIANovasti. (2007). Heart disease kills 1.3 million annually in Russia-chief cardiologist Retrieved from: http://en.rian.ru/russia/20070214/60721668.html on January 21, 2011.

RIANovasti. (2010). Natural population decline in Russia down by 31% in 2009-Putin. Retrieved from: http://en.rian.ru/russia/20100216/157906438.html on January 21, 2011.

Rigbey, E. (2009). Drug addiction: Not quite as simple as Russia v. the West. Open democracy. Retrieved from: http://www.opendemocracy.net/content/drug-addiction-not-quite-as-simple-as-

Roberts, A. (2010). Policy Brief: Infectious diseases, HIV/AIDS in Russia. Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC. Retrieved from: samples.jbpub.com/9780763734213/34217_PBxx_InfectiousDiseasesRussia.doc

Stoner-Weiss, K, & McFaul, M (2009). Domestic and international influences on the collapse of the Soviet Union (1991) and Russia’s initial transition to democracy (1993). Center for Democracy, Development, and The Rule of Law. Retrieved from: iis-db.stanford.edu/pubs/22468....pdf on January 20, 2011.

UNAIDS. (2005). AIDS Epidemic Update: December 2005.

UNAIDS. (2011). Russian federation. Retrieved from: http://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/russianfederation/

Vancouver Sun. (2011). 15 top alcohol-consuming countries in the world. The Vancouver Sun. Retrieved from http://www.vancouversun.com/health/alcohol+consuming+countries+world/4496427/story.html

World Bank, The. (2011). HIV/AIDS in the Russian federation. The World Bank. Retrieved from: http://web.worldbank.org/...

Wong, G. (2009). Russia’s bleak picture of health. CNN. Vital Signs. Retrieved from: http://edition.cnn.com/2009/HEALTH/05/19/russia.health/index.html on January 21, 2011

Wyon, J. (1996). Comment: Deteriorating health in Russia- A place for community-based approaches. American Journal of Public Health. 321 (3).

|