Gender Representation in a Selection of Children’s Picture Books:

A Skewed Ratio of Male to Female Characters?

Heather MacArthur

Carmen Poulin*

University of Brunswick

Keywords: gender, males, females, children, picture books, media content analysis

Abstract

The present research investigates the ratio of male to female characters in a selection of 92 children’s picture books chosen at random from the local library of a small Atlantic Canadian city. Results indicate that, consistent with past findings, male characters are depicted more often than female characters in the titles, cover illustrations, main characters, and page illustrations of the sample. When the results are broken down, however, it is apparent that human male and human female characters are depicted relatively equally, while male animals are represented significantly more often than female animals. Reasons for these findings and the implications for young readers are discussed.

Introduction

When considering the purpose, role, and importance of children’s literature in early childhood development, the solidification of ideas about gender and the relative visibility (or invisibility) of males and females is likely not the first thought to spring to mind. Indeed, picture books are often thought of as being politically neutral; they are assumed to be healthy and essential tools that benefit children by improving reading levels and providing mental stimulation that will lay the groundwork for future learning and education. Although there is little question that these advantages of early reading do exist (e.g., Cunningham & Stanovich, 2001), it is important that another function of these books also be acknowledged: they provide information to young readers about social norms and values (Arbuthnot, 1984; Weitzman, Eifler, Hokada, & Ross, 1972). As pointed out by Weitzman et al. (1972), children’s literature can facilitate the internalization of ideas regarding self and others, social roles, and the surrounding environment.

The concept of gender is one aspect of human society about which children’s books actively or passively teach their readers (LaDow, 1976; St. Peter, 1979; Weitzman et al., 1972). Notions regarding what are normal and acceptable behaviours for males and females may be reinforced through picture books: the activities, characteristics, and treatment of male and female characters provide children with cues about socially desirable norms. Children can then incorporate these norms into their own behaviour by imitating the readily-available behavioural models that are provided by these books (St. Peter, 1979; Weitzman et al., 1972). Before considering what children’s books tell children about the relative roles of males and females, however, the question of whether females and males are equally represented in these texts must first be addressed. Given the roughly equal proportions of males and females in society, any deviation from this ratio in books for young readers would seem to present a biased and partial account of the world to children who are just beginning to learn about it. As demonstrated in a study by Ochman (1996), unequal gender representation in children’s literature may also have consequences on the self-esteem of young readers. In her study, four groups of third-grade children were read non-gender-role stereotyped stories, by either a male or female teacher. The four groups were also differentiated according to the gender of the story’s main character. By administering a test of self-esteem to the children before and after they were read the stories, Ochman (1996) found that children who heard stories about a main character of the same gender as themselves scored significantly higher on the self-esteem measure than when they heard stories about an other-gendered character. These results suggest that the presence or absence of one gender or the other in children’s literature could have a measurable influence on the self-esteem of children.

To determine whether female and male characters are equally represented in children’s books, a landmark study was undertaken by Weitzman, Eifler, Hokada, and Ross in 1972. These researchers found that males and females were not depicted equally: females were under-represented in the titles, characters, illustrations, and storylines of Caldecott award-winning, Newberry award-winning, and Little Golden books, as well as children’s books on etiquette. Since that time, several other studies have investigated the ratio of females to males in children’s literature, and only one (Gooden & Gooden, 2001) has shown a relatively equal number of male and female main characters (though male characters still significantly outnumbered female characters in the page illustrations of their sample). Otherwise, it has consistently been found that female characters are portrayed in these books less often than male characters (e.g., Clark, Guilmain, Saucier, & Tavarez, 2003; Hamilton, Anderson, Broaddus, & Young, 2006; St. Peter, 1979). Of the skewed gender ratios observed in children’s picture books, Weitzman et al. concluded, “[c]hildren scanning the list of titles of what have been designated as the very best children's books are bound to receive the impression that girls are not very important because no one has bothered to write books about them” (p. 1129).

The consistent under-representation of female characters in children’s literature cannot be considered a chance occurrence. Rather, it can be argued that such unbalanced gender ratios reflect a broader culture that continues to afford higher status to males than to females. Indeed, women have been found to be relatively invisible in a number of other media, including television programs (Signorielli & Bacue, 1999), popular films (Lauzen & Dozier, 2005), newspaper comic strips (Glascock & Preston-Schreck, 2004), and news magazine covers (Dodd, Foerch, & Anderson, 1988). Furthermore, we continue to live in a world where college-educated women earn less than college educated men (Bobbitt-Zeher, 2007) and where violence against women remains rampant around the world (United Nations, 2010), to name just a couple of indicators of women’s present status in society.

Considering the impact that gender representation in children’s literature has on the self-esteem of children, as well as the role it plays in indicating the status of women more broadly, it is essential that these books continue to be monitored for the equal representation of female and male characters. The last known study on this matter was conducted by Hamilton et al. in 2006; therefore, the purpose of the present study is to undertake a more recent survey of the books available to young readers today. Given the existing evidence to suggest that females have been relatively excluded from children’s literature to date, it is expected that a current analysis of gender representation in children’s picture books will remain consistent with previous findings. It is hypothesized, therefore, that females will be represented significantly less often than males in book titles, cover illustrations, page illustrations, and as main characters.

Method

Sample Selection

The majority of past studies investigating gender in children’s picture books have based their samples on award-winning literature (e.g., Caldecott and American Library Association award-winners). Although award-winning books are popular and widely read, they may not be representative of the majority of picture books that are available to children, as they exemplify the highest quality of children’s literature available. Indeed, although it is not explicitly mentioned in the criteria for the award selection process, some of these award-winners may well be chosen by judges who are conscientious about the need for equal gender representation in children’s books. For this reason, the present study will follow the lead of La Dow (1976), Barnett (1986), and McDonald (1989) in basing its selection of children’s books on the available collection at a local public library. This method allows for the generation of a more representative sample and can provide insight as to the gender composition of books that a child might encounter on a typical trip to the city library. A total of 92 children’s books were chosen from the public library of a small Atlantic Canadian city with a population of approximately 50,000. In order to ensure that selection was random, the sixth book from the left and right side of each shelf within the library’s children’s section was chosen for inclusion in the study (Appendix A). Overall, the selected sample represented a total of 87 different authors, with dates of publication ranging from 1956 to 2010 (a 54-year period). Thirty-three of the books were published in the 2000s, another 33 during the 1990s, 15 in the 1980s, 5 in the 1970s, 4 in the 1960s, and 2 in the 1950s. The mean date of publication was 1994, and the median was 1992.Procedure

To analyze the gender content of the sample, each of the selected books was examined to determine whether any references to male or female characters were present in the title. Next, the gender of the main character(s) was coded, and the gender represented in each book’s cover illustration was analyzed. Finally, each page was examined, from the inside front cover to the inside back cover, to identify the gender of all illustrated figure(s).

Borrowing from the methodology of Gooden and Gooden (2001), each title, main character, cover illustration, and page illustration was coded as belonging to one of the following categories: male, female, equal (human), male animal, female animal, equal (animal), or neutral. When there were multiple figures depicted, an illustration was classified as “female” if there were more female figures present than male figures and as “male” if there were more male figures shown. The illustration was classified as “equal (human)” if there were an equal number of male and female figures. The same procedure was followed for animal illustrations, which could be classified as “male animal,” “female animal,” or “equal (animal).” When it was difficult to ascertain whether a character was male or female, which was especially problematic in the case of certain animal figures, the approach described by Hamilton et al. (2006) was employed. If the figure was referred to in the text, it was often possible to determine the gender based on the descriptive pronoun used. If the ambiguous figure was not referred to in the text, visual indicators such as clothing and facial features were used to make a classification, as a child would likely do. If in the end there were no cues given for identification, the figure was considered neutral.

Results

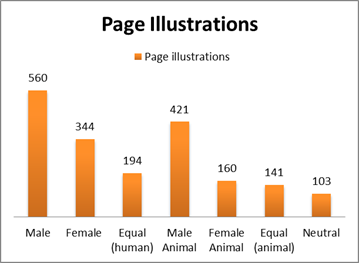

Figure 1Page illustrations

There were a total of 1923 page illustrations contained within the 92 books of the sample. As shown in Figure 1, 560 (29.12%) of these contained mostly human male characters, 344 (17.89%) contained mostly human female characters, and 194 (10.09%) contained an equal number of human males and females. To determine whether the number of human male and human female illustrations was significantly different, a Student’s t-test was performed, and the results revealed that human male characters were represented significantly more often than human female characters in page illustrations, t= 2.810, p<. 05.Looking at the gender breakdown within the animal portion of the illustrations, 421 (21.89%) of the sample’s illustrations were made up mainly of male animals, while 160 (8.32%) contained mainly female animals. A further 141 (7.33%) illustrations were categorizes as “equal (animal)”. A t-test comparing the illustrations of male and female animals revealed that male animals were depicted in significantly more illustrations than female animals, t=3.675, p<.001.

Taken together, 981 (51.01%) of the illustrations contained mostly male characters (either human or animal), and 504 (26.21%) contained mostly female characters. Using these data to perform a t-test, it was found that male characters were represented in page illustrations significantly more often than female characters, t= 6.099, p<.001.

Titles

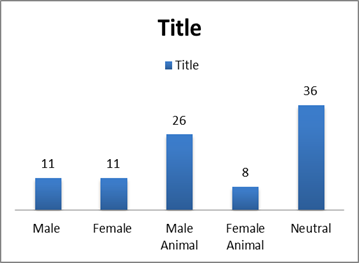

Figure 2As shown in Figure 2, human female and human male title references were equally prevalent with 11 (11.96%) references each. Therefore, there was no significant difference found between human male and female title references within the sample.

Male animal title references were present in 26 (28.26%) of the books, and references to female animals were contained in 8 (9.45%) of the titles. To determine if this represented a significant gender difference in title references, a Student’s t-test was performed, and the results indicated that male animals were represented significantly more often than female animals in children’s book titles, t=4.144, p<.001.

Collapsing the human and animal categories, male characters were referenced in 37 (40.22%) of the titles, while female characters were referenced in 19 (20.65%). A t–test revealed that this difference was significant: males were represented significantly more often than females in the titles of the sample, t(91) =3.807, p<.001.Cover illustrations

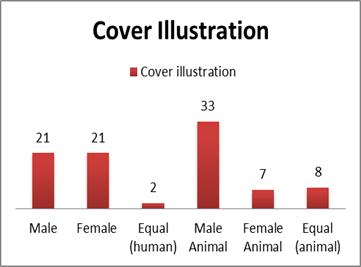

Figure 3

Figure 3 depicts the gender proportions present in the sample’s 92 cover illustrations. Human males and females were equally represented on the book’s covers, with 21 (22.83%) illustrations each, while 2 (2.17%) of the book covers had an equal number of female and male humans. As such, human female and human male cover illustrations were not found to be statistically different.

With regards to cover illustrations of animals, male animals were depicted in 33 (35.87%) of the covers, and female animals were depicted on 7 (7.61%). Eight (8.7%) of the covers contained an equal number of male and female animals. Using these data to perform a Student’s t-test, it was revealed that male animals were represented significantly more often than female animals in the cover illustrations of the sample, t= 5.621, p<.001.When the human and animal categories were combined, male characters were predominant in a total of 54 (58.7%) cover illustrations of the sample, while females were predominant in a total of 28 (30.43%). T-test results showed that males were represented significantly more often than females in the cover illustrations of the sample, t= 5.476, p<.001.

Main characters

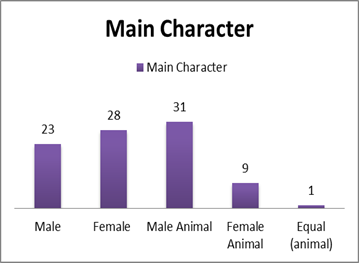

Figure 4

As depicted in Figure 4, human males were represented as main characters in 23 (25%) of the 92 books, while human females were represented as main characters in 28 (30.43%) of the books. The results of a t-test indicated that this difference was not statistically significant.

Male animals were main characters in 31 (33.7%) of the books, while female animals were main characters in 9 (9.78%). One (1.09%) of the picture books had an equal number of female and male main characters. A Student’s t-test performed using these data revealed that male animals were represented significantly more often than female animals as main characters, t=4.827, p=<.001.

Combining the human and animal categories, a male human or animal was the main character in 54 (58.7%) books, while a female human or animal was protrayed as the main character in 37 (40.22%) books of the sample. According to the results of a t-test, males were represented significantly more often than females as main characters in the books, t=3.579, p=<.001.

Discussion

When human and animal characters were collapsed into a single category, the present study’s sample of 92 children’s books was found to contain significantly more male than female characters in each of the four categories that were assessed: page illustrations, titles, cover illustrations, and main characters. These findings are consistent with past studies investigating gender ratios in books for young readers (e.g., Clark et al., 2003; Hamilton et al., 2006; LaDow, 1976; St. Peter, 1979), which have reliably found females to be under-represented in the title references, main characters, page illustrations and cover illustrations of children’s picture books.

When human and animal characters were analyzed separately, however, a different story emerged: representations of human males and females were found to be equal or statistically similar in all but one of the analytical categories of the sample (page illustrations being the only category in which human males significantly outnumbered human females). Male animals, on the other hand, were represented significantly more often than female animals in all four categories (titles, main characters, page illustrations, and cover illustrations). This inconsistency between the gender ratio of human characters and the gender ratio of animal characters was also seen in the findings of Gooden and Gooden (2001) and LaDow (1974), although it was not formally acknowledged by either author. One possible explanation for this pattern of results is that while conscious efforts to improve the visibility of females in children’s literature have led to the inclusion of female characters in the most obvious and seemingly important aspects of books for young readers (such as depictions of human characters), an adherence to the internalized standard of the “male as normative” occurs with apparently less important details, such as the depiction of animals (Hyde, 1996). Thus, when conscious efforts are not being made to increase the visibility of females, as might be the case when drafting these less obvious features of a children’s book, the number of female depictions may decrease.

Whatever the reason, the continuation of gender inequality in children’s books is problematic, as it suggests that a male bias remains pervasive in both children’s books and society more broadly. The relative absence of females in these books informs children that females are not active participants in the world to the same degree as males; if Ochman’s (1996) conclusions are correct, this may have significant implications for the psychological development of both genders. Clearly, there remains a great deal of work to be done before gender equality can be taken for granted in children’s literature, as well as in all other important aspects of society.

In order to prevent the negative consequences that a distorted gender ratio in children’s literature may have on young readers, it is important that parents, teachers, librarians, and everyone involved in the upbringing and education of young children choose reading materials carefully and with a full awareness of the implicit messages that these materials may be transmitting to children. Furthermore, increasing awareness about the relative invisibility of females in children’s literature, as well as in various other literatures and media, may help propel efforts to reverse this trend by encouraging authors and publishers to seek gender equality in their manuscripts.

Limitations and Future Research

The major limitation of this study involves the fact that its sample was composed of a random selection of children’s books chosen from one local library in a small Canadian city. Although the results provide some insight as to the gender composition of the books that might be encountered by a child at this library, it cannot be certain that the results are generalizable to other North American public libraries. Library collections may differ significantly from community to community, and thus what is applicable in one may not be applicable in another.

A second limitation of the study is that the sample was coded for gender by only one rater: the primary author. Had a second rater also classified the titles, cover illustrations, main characters, and page illustrations of the sample, calculations of inter-rater reliability would have been possible. With just one rater, however, the reliability of the gender coding cannot be confirmed.

Another limitation that should be considered involves the fact that the present study’s sample consisted of children’s literature published over a broad timespan, including books published in the 1950s and 1960s. For this reason, it was not possible to clearly establish whether or not gender equality has improved in children’s books published more recently, and this is an important area for further study. Indeed, investigating gender representation in books published since 2000 would help to ascertain whether the relative invisibility of females in children’s picture books has improved over recent years and might also provide some insight as to what can be expected of these books in the future.

Finally, it must be acknowledged that the books chosen for inclusion in the present study were not necessarily the most popular or frequently-read within the library’s collection. Consequently, further studies should be undertaken to investigate the gender composition of books that children are actually known to be reading. This could be achieved by retreiving a list of the most recently checked-out children’s books from the local library, thus helping to determine whether the books that are actually reaching children exhibit the same gender bias as has been found in past research.

References

Arbuthnot, M. H. (1984). Children and books. Chicago, IL: Scott Foresman & Company.

Barnett, M. A. (1986). Sex bias in the helping behavior presented in children's picture books. Journal of Genetic Psychology, 147, 343-351.

Bobbitt-Zeher, D. (2007). The gender income gap and the role of education. Sociology of Education, 80, 1-22. doi:10.1177/003804070708000101

Clark, R., Guilmain, J., Saucier, P. K., & Tavarez, J. (2003). Two steps forward, one step back: The presence of female characters and gender stereotyping in award-winning picture books between the 1930s and the 1960s. Sex Roles, 49, 439-449. doi: 10.1023/A:1025820404277

Cunningham, A. E., & Stanovich, K. E. (2001) What reading does for the mind. Journal of Direct Instruction, 1, 137-149. Retrieved from http://www.csun.edu/~krowlands/Content/....pdf

Dodd, D. K., Foerch, B. J., & Anderson, H. T. (1988). Content analysis of women and racial minorities as news magazine cover persons. Journal of Social Behavior & Personality, 3, 231-236.

Glascock, J., & Preston-Schreck, C. (2004). Gender and racial stereotypes in daily newspaper comics: A time-honored tradition? Sex Roles, 51, 423-431. doi:10.1023/B:SERS.0000049231.67432.a9

Gooden, A. M., & Gooden, M. A. (2001). Gender representation in notable children’s picture books: 1995-1999. Sex Roles, 45, 89-101. doi: 10.1023/A:1013064418674

Hamilton, M. C., Anderson, D., Broaddus, M., & Young, K. (2006). Gender stereotyping and under-representation of female characters in 200 popular children’s picture books: A twenty-first century update. Sex Roles, 55, 757-765. doi: 10.1007/s11199-006-9128-6

Hyde, J. S. (1996). The psychology of women: Half the human experience (5th ed.). Lexington, MA: D.C Health and Company.

LaDow, S. (1976). A content-analysis of selected picture books examining the portrayal of sex roles and representation of males and females. East Lansing, MI: National Center for Research on Teacher Learning.

Lauzen, M. M., & Dozier, D. M. (2005). Maintaining the double standard: Portrayals of age and gender in popular films. Sex Roles, 52, 437-446. doi:10.1007/s11199-005-3710-1

McDonald, S. M. (1989). Sex bias in the representation of male and female characters in children's picture books. Journal of Genetic Psychology, 150, 389-401.

Ochman, J. M. (1996). The effects of non-gender-role stereotyped, same-sex role models in storybooks on self-esteem of children in grade three. Sex Roles, 35, 711-736. doi: 10.1007/BF01544088

Signorielli, N., & Bacue, A. (1999). Recognition and respect: A content analysis of prime-time television characters across three decades. Sex Roles, 40, 527-544. doi:10.1023/A:1018883912900

St. Peter, S. (1979). Jack went up the hill… but where was Jill? Psychology of Women Quarterly, 4, 256-260. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.1979.tb00712.x

United Nations. (2010). The world’s women: Trends and statistics. Retrieved on June 12, 2011, from http://unstats.un.org/unsd/demographic/products/Worldswomen/wwVaw2010.htm.

Weitzman, L. J., Eiffel, D., Hokada, E., & Ross, C. (1972). Sex-role socialization in picture books for preschool children. American Journal of Sociology, 77, 1125-1150.

Note: The Authors would like to thank Dr. Lynne Gouliquer for her contributions to the revision of this manuscript.

Appendix A- Bibliographic Information for Children’s Book Sample

Abbass Nearing, Frances. (1994). Herbie the lawnmower. Halifax: Tommy Tunes Publishing.

Alexander, M. (2003). I’ll never share you, Blackboard Bear. Cambridge, MA: Candlewick Press.

Amoss, B. (1971). Old Hasdrubal and the pirates. New York: Parents’ Magazine Press.

Awdry, W. (1992). A cow on the line. New York: Random House.

Blanco, A. (1994). Angel’s kite. Emeryville, CA: Children’s Book Press.

Bouchard, D. (2002). The song within my heart. Vancouver: Rain Coast Books.

Brenner, B. (1975). Cunningham’s rooster. New York: Parents’ Magazine Press.

Brett, J. (1991). Berlioz the bear. New York: Penguin Putnam Books for Young Readers.

Bridwell, N. (1984). Clifford’s family. New York: Scholastic.

Briggs, R. (1975). Father Christmas goes on holiday. London: Hamish Hamilton.

Bushey, J. (1994). A sled dog for Moshi. Winnipeg: Hyperion Press.

Cannon, J. (1993). Stellaluna. San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Carle, E. (1969). The very hungry caterpillar. New York: Philomel Books.

Carrick, C. (1976). The accident. New York: The Seabury Press.

Coerr, E. (1981). The big balloon race. New York: Harper Collins.

Cole, J. (2008). The adventures of Tiggy Tiger, the three-legged tomcat. Halifax: Transcontinental Specialty Publications.

Cooney, B. (1982). Miss Rumphius. New York: Puffin Books.

Cousins, L. (2001). Maisy at the fair. Cambridge, MA: Candlewick Press.

Curtis, J. L. (1996). Tell me again about the night I was born. Markham, ON: Scholastic Canada.

Diamond Goldin, B. (1990). The world’s birthday. San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Doner, K. (1999). Buffalo dreams. Portland: Westwinds Press.

Duchesne, C. (1998). Edmund the terrible raccoon. Sainte-Lambert, QC: Dominique et Compagnie.

Duvoisin, R. (1965). Petunia, I love you. Toronto: Random House Canada.

Eaton Hume, S. (1997). Rainbow bay. Vancouver: Raincoast Books.

Emberley, M. (1993). Welcome back sun. Toronto: Little, Brown and Company.

Falconer, I. (2010). Olivia goes to Venice. New York: Atheneum Books for Young Readers.

Fernandes, E. (1994). The tree that grew to the moon. Richmond Hill, ON: Scholastic Canada.

Fernandes, E. (1997). Little Toby and the big hair. Toronto: Doubleday Canada.

Fitch, S. (1992). There were monkeys in my kitchen. Toronto: Doubleday.

Fitz-Gibbon, S. (2002). Two shoes, blue shoes, new shoes! Markham, ON: Fitzhenry and Whiteside.

Freeman, D. (1992). Rhymes and riddles with Corduroy. New York: Grosset and Dunlap.

Froissart, B. (1990). Uncle Henry’s dinner guests. Toronto: Annick Press.

Garland, M. (2001). Mystery mansion. New York: Penguin Putnam Books for Young Readers.

Gauch, P. L. (1999). Presenting Tanya the ugly duckling. New York: Penguin Putnam Books for Young Readers.

Gay, M. L. (2005). Caramba. Toronto: Groundwood Books.

Gerstein, M. (1987). The mountains of Tibet. New York: Harper and Row.

Gilman, P. (1986). Little blue Ben. Richmond Hill, ON: Scholastic.

Gilman, P. (1990). Grandma and the pirates. Richmond Hill, ON: North Winds Press.

Gleeson, B. (1997). Koi and the kola nuts. New York: Rabbit Ears Books.

Graham, A. (1987). Educating Arthur. Milwaukee: Gareth Stevens Children’s Books.

Grambling, L. G. (2002). Grandma tells a story. Watertown, MA: Charsbridge Publishing.

deGroat, D. (2004). Good night, sleep tight, don’t let the bedbugs bite! New York: Scholastic.

Henkes, K. (1996). Chrysanthemum. New York: Greenwillow Books.

Hennessy, B. G. (1989). The missing tarts. New York: Scholastic.

Herriot, J. (1977). Oscar, cat-about-town. London: Troll Associates.

Higgins, N. (2008). Aye, my eye! Edine, MN: ABDO Publishing Group.

Hill, E. (1984). Spot goes to school. London: Puffin Books.

Hodgson Burnett, F. (2005). A little princess. London: Usborne Publishing Ltd.

Howard, G. (2001). William’s house. Brookfield, CN: The Millbrook Press.

Hutchins, H. (1989). Norman’s snowball. Toronto: Annick Press.

Hutchins, H. (1999). One duck. Toronto: Annick Press.

Jackson, C. (2003). The Gaggle sisters sing again. Montreal: Lobster Press.

Jeffers, O. (2005). Lost and found. London: Harper Collins Children’s Books.

Kahl, V. (1956). Maxie. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Kassirer, S. (1992). The Adventures of Pinocchio. New York: Random House.

Kellerhals-Stewart, H. (1999). Brave highland heart. Toronto: Stoddart Kids.

Lester, H. (2000). Tacky and the emperor. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.

Lesynski, L. (2001). Night school. Toronto: Annick Press.

Lind, A. (1994). Black bear cubs. Norwalk, CN: Soundprints.

Lindaman, M. (1958). Flicka, Ricka, Dicka go to market. Chicago: Albert Whitman and Company.

Ljungkvist, L. (2010). Pepi sings a new song. New York: Beach Lane Books.

Lobel, A. (1966). The troll music. New York: Harper and Row.

Lobel, A. (1967). Potatoes potatoes. New York: Harper and Row.

Montanari, E. (2009). Chasing Degas. New York: Abrams Books for Young Readers.

MacDonald, H. (2010). Crosby and me. Charlottetown: The Acorn Press.

Manson, A. (1995). Just like new. Toronto: Groundwood Books.

Marsoli, L. A. (2003). A Tiggerific band. United States: Advance Publishers.

Marton, J. (1989). I’ll do it myself. Toronto: Annick Press.

Mayer, M. (1988). Just my friend and me. New York: Western Publishing Company.

McPhail, D. (1982). Snow lion. New York: Parents Magazine Press.

Mockford, C. (2000). Cleo the cat. New York: Barefoot Books.

Monroe, C. (2010). Sneaky sheep. Minneapolis: Carolrhoda Books.

Moore, I. (1980). Aktil’s big swim. Melbourne: Oxford UP.

Munsch, R. (1990). Good families don’t. Toronto: Doubleday Canada.

Palatini, M. (2009). Boo-hoo moo. New York: Harper Collins.

Parent, N. (2000). Winnie the Pooh : Home sweet home. United States: Advance Publishers.

Patience, J. (1988). Toddy and the fox. Bridlington, UK: Peter Haddock Ltd.

Phillips Denslow, S. (1995). On the trail with Miss Pace. New York: Simon and Schuster Books for Young Readers.

Rayner, C. (2006). Augustus and his smile. London: Little Tiger Press.

Rayner, C. (2009). Ernest. London: MacMillan Children’s Books.

Roth, R. (1993). The sign painter’s dream. New York: Crown Publishers Inc.

Russo, M. (2007). The bunnies are not in their beds. New York: Swartz and Wade Books.

Ruurs, M. (1996). A mountain alphabet. Toronto: Tundra Books.

Ryder, J. (2006). My mother’s voice. New York: Harper Collins.

Schick, E. (2000). Mama. New York: Marshall Cavendish.

Shaw, M. (2004). Brady Brady and the MVP. Waterloo, ON: Brady Brady.

Spinelli, E. (2009). Miss Fox’s class goes green. Morton Grove, IL: Albert Whitman and Company.

Steg, W. (1982). Doctor De Soto. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Sykes, J. (1997). Dora’s eggs. Waukesha, WI: Little Tiger Press.

Tibo, G. (1997). Simon at the circus. Toronto: Tundra Books.

Treeman, D. (2000). Corduroy at the zoo. New York: Penguin Book for Young Readers.

Tusa, T. (1998). Bunnies in my head. Houston: University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center.

|