Individualistic and Structural Attributions of Poverty in the LDS Population

Alex North

Arwen Behrends

Kayla Green

Luis Oquendo

Tamra Dison

Justin Larson

Yohan Delton*

Brigham Young University-Idaho

Abstract

A significant amount of research has been conducted on the lay attributions of poverty and the subsequent influence on helping behavior. The purpose of this study was to further the work on how religion mediates poverty attributions by extending the research into a LDS population. As the result of the high conservative influence in the LDS sample, we hypothesized that the individualistic attribution would be the more popular choice. There were 144 BYU-Idaho students that filled out an Internet survey. This survey used a five-point scale to measure students’ attributions of poverty. A factor analysis revealed six factors that accounted for 62.9 percent of the variance, while an ANOVA test showed that individualistic and structural attributions were used more than fatalistic attributions to explain poverty. Our hypothesis was only partially supported. It appears that religious influence reduced the effect that political orientation exerted on poverty attribution. A limitation in our study is our relatively homogenous sample. Future research needs to be conducted to flesh out why religion exerts influence on poverty attributions.

Introduction

Recent estimates of poverty showed that 1.4 billion people in developing countries were living in poverty (World Bank Group, 2010). Even in the United States 13.2 percent of the population was estimated to be below the poverty threshold (Bishaw, & Renwick, 2009). Because of the prevalence of poverty in the world a significant amount of research has been conducted on the lay attributions of poverty and the subsequent influence on helping behavior (Wilson, 1996; Hine, & Montiel, 1999).

Research has shown that perceptions of poverty were often identified in one of three groups. The first group emphasized individualistic explanations. These highlight individual responsibility and characterological weaknesses on the part of the poor. Structural explanations, on the other hand, emphasized the economy, exploitation by corrupt corporations, and irresponsible government. The third group emphasized fatalistic explanations, such as, bad luck or the will of God (Hine & Montiel, 1999; Nasser, Singhal, & Abouchedid, 2005).

Several patterns were found in certain groups relative to their attributions of poverty. For instance, Zucker and Weiner (1993) found that “Conservatives generally rate individualistic causes as being more important than do liberals who, in turn, rate societal and fatalistic causes as being more important than do conservatives" (p. 940). This finding was also reported by Williams (1984). Although many findings are robust, some studies conflict (see amount of education in relation to poverty attributions in Alston, & Dean, 1972, contrasted with Feagin, 1972).

Another interesting pattern dealt with religious affiliation and poverty attribution. Feagin (1972) and Feather (1974) found that Protestants were more likely than Catholics to attribute poverty to individual causes, both in an American sample and a non-American sample. However, Feagin (1972) found that black Protestants were most likely to use structural explanations. This study sought to further work on religious attributions of poverty by surveying another Christian population: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (LDS).

In that many of the beliefs of the LDS church can be considered conservative, especially in terms of definitions of marriage and family and in an emphasis on traditional values, we felt that this relation to conservative values would also be reflected in the poverty attributions of a LDS sample. Thus, our hypothesis was that a LDS sample would attribute poverty mainly to individual factors.

Methods

ParticipantsThe participants in this study were obtained through a random sample of 144 Brigham Young University-Idaho students who received an Internet based survey via e-mail

ProcedureThe participants received an e-mail that linked them to a survey of 25 questions (from Nasser, Singhal, & Abouchedid, 2005). These questions were rated on a 5-point scale. The instructions as well as a sample of questions are listed below:

Instructions:

The statements below depict some beliefs about poverty and poor people in the country and seek to know your own beliefs about them as different theses are advanced about their plight. There are no right or wrong responses. Please read one statement at a time and rate these on a five-point scale in the light of your beliefs, perceptions, and understanding of your own situation. For the next questions, answer according to this key: Fully Agree=5, Partly Agree=4, Neither Agree Nor Disagree=3, Partly Disagree=2, Fully Disagree=1

Sample Questions:

I think in this country many persons are poor because

- There are many workers who are available for work at low wage.

- The government lacks good money management.

- The government is unable to provide education for all.

- The government is unable to provide health for all.

- People find that the culture puts on them too many social obligations (spending on relatives' gifts).

Results

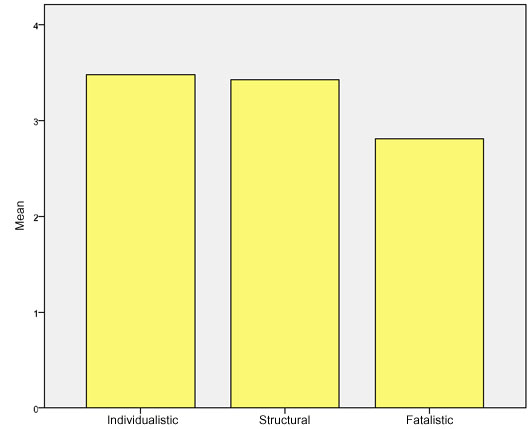

The results were analyzed by a repeated measures ANOVA, which showed that the level of agreement was different across poverty attribution types, F (1.98, 845.13) = 93.08, p < .05. The mean scores indicated that there was significantly less agreement on the fatalistic attributions (M = 2.61, SD = 1.28) than on both the individual (M = 3.35, SD = 1.12) and the structural (M = 3.68, SD = 1.16) attributions. That is, the sample agreed more with the individual and structural attributions than with fatalistic attributions. The paired sample t-tests revealed that the fatalistic and individualistic pair was significantly different, t(428) = -8.802, p < .05, as was the fatalistic and structural pair, t(428) = -13.282, p < .05. There was not a significant difference between structural and individualistic attributions, t(1000) = -.594, p > .05. Thus, our sample attributed poverty most strongly to individual and structural causes without a significant difference between the two (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Mean Scores of Poverty Attributions in a LDS Sample

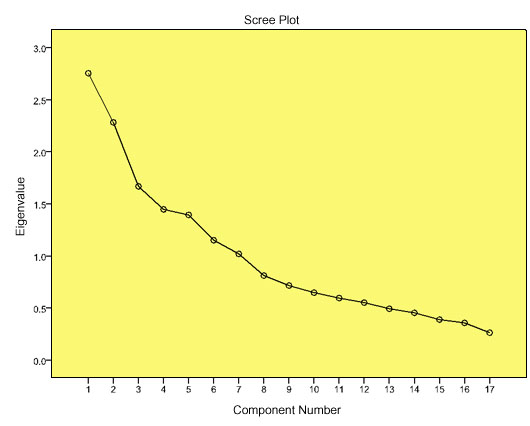

The items were analyzed with the principal component solution and Varimax rotation (see Figure 2). This analysis reduced the 17 items into six factors that accounted for 62.9 percent of the variance (see Table 1). The first factor, disposition of the poor, accounted for 16.19 percent of the variance. The loading items attributed poverty to human dispositions and lack of adequate effort on the part of the poor. The second factor, government, accounted for 13.42 percent of the variance. The three loading items attributed poverty to the government’s inability to provide healthcare and education and the government’s lack of money management. The third factor, politics, accounted for 9.81 percent of the variance. The two loading items attributed poverty to governmental policies and politics. The fourth factor, destiny, accounted for 8.51 percent of the variance. The two loading items attributed poverty to the poor’s destiny to be poor and God’s will. The fifth factor, external forces, accounted for 8.2 percent of the variance. The two loading items attributed poverty to the poor being frequently sick and handicapped and to falling prey to social evils. The last factor, uncontrollable external forces, accounted for 6.77 percent of the variance. There was one loading item, which attributed poverty to forces that cannot be understood or controlled.

Figure 2. Scree Plot showing the amount of variance explained by the factor analysis.

Table 1. Factor Analysis of Poverty Items

Factor Name

Items

Factor Loadings

Variance

Individualistic (Internal)

Poor human dispositions

Lack of adequate effort by poor

.876

.816

16.19%

Government (Structuralism)

Gov. unable to provide healthcare

Gov. unable to provide education

Gov. lacks money management

.845

.834

.578

13.42%

Politics (Structuralism)

Gov. policies add to suffering of poor

Politics ensure that poor remain poor

.829

.815

9.81%

Destiny (Fatalistic)

Poor are destined to be poor

It is the will of God for them

.883

.793

8.51%

External Forces (individualistic)

Poor are frequently sick and handicapped

Poor fall prey to social evils

.801

.782

8.2%

External Forces (uncontrollable)

There are external forces that we cannot understand or control

.851

6.77%

Discussion

The results of the study highlight the importance of religion as a mediating variable in poverty attributions. The hypothesis that a LDS population would make individualistic attributions was partially supported in that the individualistic and structural attributions were not significantly different. Due to the conservative influence, we believed that our sample would have an individualistic attribution (Zucker & Weiner, 1993). However, it seems that religion may have padded the impact that political views may have had. That is, the religious influence seemed to reduce the impact that political ideology exerted on poverty attribution. Self-categorization theory may help to explain these results. Self-categorization theory holds that certain groups can become psychologically significant to its members, such that, the group becomes important in determining behavior of the members (Hogg, 2004). Hence, it is possible that the LDS religion may be more psychologically significant to its members than their political ideology, causing the strong effect of Conservatism to be lessened in our sample.

Hine and Montiel (1999) identified an unexamined assumption in the poverty attribution literature. They noted that, “Although researchers often assume that poverty attributions are an important determinant of decisions to help or not to help the poor, few (if any) studies have tested this proposition directly” (p. 945). In their study they included a questionnaire purportedly linking attributions to helping behavior. In their questionnaire they asked how often respondents had engaged in certain helping behaviors, such as writing a letter to a government official, attending a meeting dealing with antipoverty actions, or making a phone call. Their study showed that helping behavior was moderately correlated with a structural attribution. So, they concluded that a structural attribution increased helping behavior. However, they only measured the type of helping behavior one would engage in if one held a structural attribution of poverty. In fact, it seems that the type of helping behavior engaged in is a function of the type of attribution made. For instance, Brooks (2006) showed that Conservatives donate substantially more to charitable organizations than Liberals. This finding contradicts the assumption that only a structural view is correlated with helping behavior, because Conservatism is associated with individualistic assumptions. Hence, it is false to say that one type of attribution is more associated with helping behavior than another. It seems more likely that the type of attribution you make determines the type of helping behavior and that whether or not your help is dependent on other mediating variables. In short, people from all types of attributions help, but how one helps is dependent on how one attributes.

Our study is related to the work of Feagin (1972) and Feather (1974), who found that Protestants were more likely than Catholics to attribute poverty to individualistic causes, while Catholics were more likely to attribute poverty to structural causes. Thus, it seems that the LDS theology partially supports both attributions without excluding the other. A limitation of the study is that the sample contained university students from a middle class background. Thus, the homogeneity of our sample may not be representative of the LDS population as a whole. Also, the Conservative influence was inferred from the moral standards and principles of our sample. So, the Conservative influence may not be as strong as supposed. Future research is needed to directly measure political ideology with religion to examine the effects. Also, more work needs to be done to flesh out why religion exerts influence on poverty attributions. Further, future research should examine the assumption that poverty attributions directly influence helping behavior.

References

Alston, J. P., & Dean, K. I. (1972). Socioeconomic factors associated with attitudes toward welfare recipients and the causes of poverty. The Social Service Review, 46, 13-23.

Bishaw, A., & Renwick, T. J. (U.S. Census Bureau). (2009). Poverty: 2007 and 2008 American Community Surveys. Retrieved from, http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/poverty/data/acs/2008/index.html.

Brooks, A. C. (2006). Who really cares: America’s charity divide, who gives, who doesn’t, and why it matters. New York: Basic Books.

Feagin, J. R. (1972). Poverty: We still believe that God helps those who help themselves. Psychology Today, (November), 101-129.

Feather, N. T. (1974). Explanations of poverty in Australian and American samples. Australian Journal of Psychology, 26, 199-216.

Hine, D. W., & Montiel, C. J. (1999). Poverty in developing nations: A cross-cultural attributional analysis. European Journal of Social Psychology, 29, 943-959.

Hogg, M. A. (2004). Social categorization, depersonalization, and group behavior. In M. B. Brewer & M. Hewstone (Eds.), Self and social identity. (203-231) Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Nasser, R., Sighal, S., & Abouchedid, K. (2005). Causal attributions for poverty among Indian youth. Current Research in Social Psychology, 11, 2-13.

Williams, S. (1984). Left-right ideological differences in blaming victims. Political Psychology, 5, 573-581.

Wilson, G. (1996). Toward a revised framework for examining beliefs about the causes of poverty. The Sociological Quarterly, 37, 413-428.

World Bank Group. (2010). Overview: Understanding, measuring and overcoming poverty. Retrieved from, http://web.worldbank.org/....

Zucker, G. S., & Weiner B. (1993). Conservatism and perceptions of poverty: An attributional analysis. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 23, 925-943.

Note: This research was supported by Dr. Larry L. Thurgood, Dean of the College of Education and Human Development at Brigham Young University-Idaho. We would also like to thank Dr. Scott Bergstrom, Institutional Research & Assessment Officer, for providing us with our sample.

|