Referential Communication in Bilingual and Monolingual Children

Lorraine M. Rindahl

Marie A. Stadler*

University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire

Abstract

The purpose of this project was to discover differences in the referential communication skills of bilingual and monolingual children. The children participated in two barrier tasks, one in which each child followed verbal directions and one in which they gave verbal directions, each without benefit of visual cues. Differences were found between the two groups of children with the monolingual children outperforming the bilingual children with receiving and giving verbal directions, even though the bilingual children were considered fluent in English.

Literature Review

“The ability of a speaker to select and verbally code the characteristics or attributes of a given referent in a manner that will enable a listener to accurately identify that referent is known as referential communication” (Bowman, 1984, p. 93). There are five basic components of referential communication: speaker, listener, task, message, and listener response (Preston, 1984). Referential communication is a skill that crosses several different language components, including semantics, syntax, and pragmatics. Semantics is a system of rules that govern the meaning or content of words and their combinations (Owens, 2008). This is important to referential communication so that an individual knows the meanings of words as well as which words overlap vs. which ones are mutually exclusive. For example: “to the right of” and “beside” share meaning, though “beside” and “underneath” do not. Syntax is the structure of sentences. Referential communication requires an individual to understand syntax in order to properly give or follow directions. For example, “Put the arrow above the house,” has a different meaning from, “Put the house above the arrow.” Pragmatics is the study of language in context and involves the social rules of a language. It involves how one uses language to communicate an idea (Owens, 2008). Pragmatics are used when individuals vary their speaking style to match their audience; they would speak differently to a preschooler than to a coworker. Another pragmatic skill, one used in referential communication, is taking another’s perspective and involves speaking so that the listener will comprehend the information.

Taking another’s perspective is a referential communication skill that allows a speaker to decide what information the listener needs to hear. It is said that being able to make comparisons between referents and provide necessary contrasting information are important speaker skills (Bunce, 1991). Referential communication is a skill that is acquired during childhood, and generally a speaker’s ability to consider the listener’s perspective is established by age 10 (Sonnenschein & Whitehurst, 1984). Oller (2005) stated that “there is growing agreement and empirical evidence that developing proficiency in any language, or modality, depends on access to the dynamic referential relations between target forms and particular persons, things, events, and relations in the world of experience (p. 92).” If this is so, referential communication is vital to a child’s language development.

Referential communication is a part of everyday conversation in the classroom, at home, and at work. A study by Rubin (1972) stated that a children’s ability to take another’s perspective might play a role in their popularity amongst their peers during the early elementary years, suggesting the social importance of this skill for young children. It is also an important component of daily classroom activity, as referential communication involves explaining things clearly and facilitating understanding. If children are unable to understand directions given to them they may experience frustration, and often failure, due to an inability to understand the instructional objectives and goals (Frymier & Houser, 2000). This lack of understanding may also lead to uncertainty, which can result in a child not liking a particular subject and a decreased likelihood that they will recall and use the material at a later time according to Frymier and Houser (2000). Some referential communication skills involve giving directions and explanations or describing objects and events (Bunce, 1989), skills that are integral to classroom activities. Although referential communication is a very important communication skill, there have been very few studies related to its development and none that could be found about the differences in referential communication skills between bilingual and monolingual children.

In a study by Brock (1986), in adult English Language Learner (ELL) classrooms, the students gave longer answers to referential questions, in which the answer required the student to add information that was not already known by the teacher, than display questions (which were defined as questions to which the questioner already knew the answer). This use of referential questions increased the amount of speaking of learners in the classroom and is thought to be an important aspect of second language acquisition. It is through repeated use of a new language, and practicing it, that a child develops language competence. Thus the more a child is asked referential questions, the more experience a child will have using language, and thus their language competence will increase. Referential communication is important to the development of ELL children in the classroom.

Solari and Gerber (2008) stated that there is a significant relationship between listening comprehension and reading comprehension in normally achieving students. They also stated that for ELL children, listening comprehension was the strongest predictor of their English reading comprehension performance. This indicates that, in both bilingual and monolingual children, listening comprehension is a predictor for future reading comprehension that is a vital part of academic success. This information provides another example of the importance of bilingual children’s development of referential communication skills.

There is growing evidence that bilingualism is beneficial to a child’s developing executive control, which is an important aspect of cognitive development (Ben-Zeev, 1977; Bialystok, 2010; Carlson & Meltzoff, 2008). Executive control is necessary for giving and following instructions with maximum efficiency. This relates to referential communication, because both executive control and referential communication involve sending messages with maximum efficiency and accuracy so that they can be correctly interpreted by the receiver. The person who is giving the directions must be descriptive and accurate in order for the receiver to follow their instructions. Given that bilingual children may experience benefits for executive control, one might expect that they could outperform monolingual children on referential communication tasks.

On the other hand, referential communication is an interpersonal communication skill. Estrada, Gomez, and Ruiz-Escalante (2009) found that in order for a child to become proficient at basic interpersonal communication skills, two to three years of immersion in a second language is necessary. At this point, a student should be able to maintain social conversation and be seen as fluent. It is not until a child has reached cognitive academic language proficiency, which takes five to seven years for most ELLs to develop, that they will be proficient enough for learning academic content (Estrada et al., 2009). This is because the language of social communication is context embedded, while language used in the classroom is decontextualized (Chamot, 1983).

According to Meshoulam (1981), children who are using a language in which they are not yet fluent will use one general word in place of multiple specific words. For example, they use the word “food” rather than specific choices (e.g., sandwich, cookie). This impairs their referential communication performance in English compared to their performance in their native language. However, Meshoulam’s study did not involve children who were considered to be fluent in the second language by peers and their educators. This raised the question: How will a child’s referential communication skills be affected once he/she is considered fluent in two languages?

It is hypothesized that becoming fluent in a second language may improve a children’s ability to give directions, since they have had more practice asking questions and following directions in two languages and have stronger executive control skills, potentially strengthening their ability to take another’s perspective. This likely would be most easily observed within a contextualized communication activity. The task for this study, a barrier activity, employed oral language and was highly contextual as the children manipulated objects. The children had almost three years of education in a second language that according to Estrada et al. (2009) is a sufficient amount of time for a child to be able to correctly utilize interpersonal communication skills.

Thus, referential communication requires one to choose the best words (semantics), put them in the right order (syntax), and take the perspective of the listener in order to know what the listener needs to hear (pragmatics). Barrier activities are referential communication tasks. Many speech-language pathologists choose to use barrier activities to improve their client’s referential communication skills. During the activity, the speaker gives directions that the listener follows within tasks such as creating a specific pattern, drawing a design, or matching pictures.

The purpose of this project was to discover any differences in the direction giving and direction following abilities of bilingual and monolingual children. The same two barrier activities were used with each child. One measured the child’s skills in following verbal directions given by the examiner and the second required the child to give verbal directions to the examiner.

Method

Participants

Ten second-grade children, 8 years to 8 years 11 months, participated in this study, using a prospective non-randomized small-group design. Half of the children were ethnically Hispanic, and half were ethnically Caucasian. Five of the children spoke Spanish as their primary language but were fluent in English as well, according to a survey filled out by their teachers; the other five spoke only English. The five children who were bilingual all spoke Spanish as their primary language at home and then learned English when they entered school. Some may have had limited English exposure through older siblings and various media sources. This same survey was used to confirm that none of the children were eligible to receive special education. The children all attended the same elementary school in a small Wisconsin town. The students were selected by their teachers, and consent forms, written in both Spanish and English, were sent home. Students with a history of speech and language impairments, as well as other special education services, were excluded from the study, with the exception of English Language Learning (ELL). The study was approved by the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire’s Institutional Review Board.

Assessment

The Test of Language Development-Primary 4 (TOLD-P:4) (Newcomer & Hammill, 2008) was used to determine the children’s expressive and receptive language skills. The TOLD-P:4 measures the language abilities of children between the ages of 4 years and 8 years 11 months. Its scores satisfy the most demanding of standards for reliability, including a minimum standard for reliability coefficient of .90 in most cases. Construct validity for each of the subtests was also high. Each child completed four subtests. Picture Vocabulary involved the researcher stating a word and asking the child to point to a picture. Relational Vocabulary required each child to tell how two words, spoken by the researcher, were alike. Syntactic Understanding involved three images and the child was asked to select the image that best described the sentence read by the researcher. Sentence Imitation required the child to repeat the sentences verbatim that were read by the researcher. These subtests were chosen to assess both semantic and syntactic abilities expressively and receptively because all of these language skills are needed to perform referential communication tasks well. Each child was assessed individually in empty classrooms in their school. The total time for these four assessments was approximately thirty minutes per child.

Experimental Task

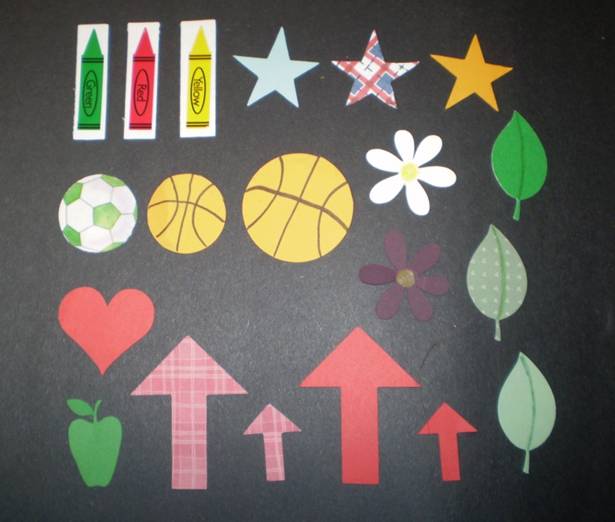

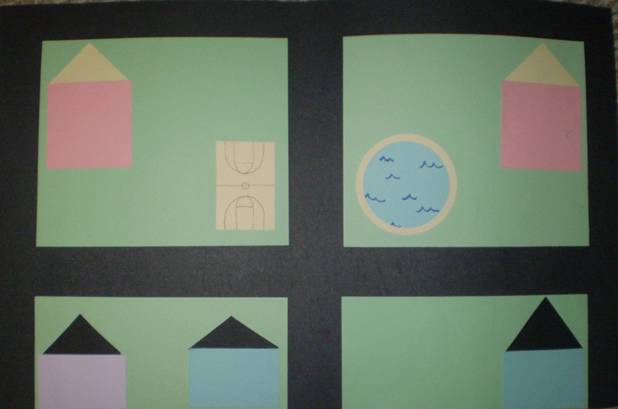

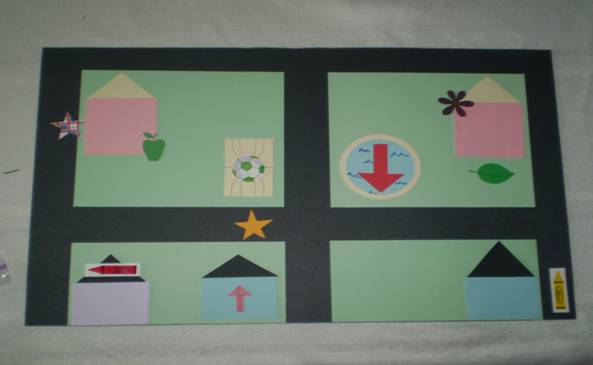

Approximately one week later, each child participated in a barrier task in which he/she first followed directions, and then gave directions, both without benefit of visual cues. These tasks were completed in an empty classroom to ensure no distractions were present. Each child performed the activity individually with only the researcher in the room. All sessions were audio recorded. Each child was given 20 graphic symbols (see Appendix A). The symbols, made of paper cutouts and stickers approximately 1 to 2 inches in size, consisted of a green crayon, red crayon, yellow crayon, blue star, patterned (red, white and blue) star, orange star, soccer ball, small basketball, big basketball, white flower, dark leaf, heart, dark (children referred to it as purple or black) flower, patterned leaf, apple, large patterned arrow, small patterned arrow, large solid arrow, small solid arrow, and light leaf. The researcher first asked the child to label each of the individual symbols, the stationary symbols on the board, and the terms left and right. When a child could not recall a symbol name, the researcher provided it. This was done to ensure that each child knew the names of every symbol. The child and researcher sat across from each other with a barrier between them to ensure no visual cues were possible. The children had a board that represented a town setting approximately 2 feet by 1 foot 6 inches (see Appendix B). Each session began with the same single trial. The researcher stated, “Put the red crayon above the basketball court.” The barrier was taken down and the researcher and child checked to see if the direction was followed correctly. Because each child followed the trial procedure correctly, no clarification was given to any of the children. This ensured that the child understood the procedures that would be used for the barrier task. The researcher then proceeded with the task by giving the child directions, one at a time, to make a specific pattern using the materials. Following each direction the researcher asked if a repetition was needed. If the child said yes the direction was repeated, but only once. If the child said no, the next direction was given. The researcher did not answer any questions, but would simply say, “Just try your best.” Each child was given the same ten directions (see Appendix C). The ten directions were of various lengths and levels of complexity and required the child to discriminate among numerous objects, colors, descriptions, and uses of left and right.

Immediately following the directions given by the researcher, the child was given a pattern (see Appendix D), and asked to give the researcher directions to recreate that pattern. Each child was given the same pattern and gave directions for all ten of the objects in the photograph (see Appendix E for correct directions). When a child skipped a direction, the researcher found the missing item, pointed to the item in the picture, and asked the child to state directions for the skipped object. This was done with each of the 10 children individually. In order to accurately perform this task, the children needed to provide explicit directions to the listener that would discriminate among 14 objects, 11 positions, 10 colors, 7 uses of left and right, and 6 descriptions (see Appendix E for critical concepts). The sessions were audio recorded and photographs were taken of the patterns created.

Each child gave the directions for all 10 of the objects. It was determined that there were 48 necessary terms that needed to be used in order to recreate the photograph correctly (see Appendix D for a copy of the photograph). There were 14 critical objects, 11 critical positions, 10 critical color terms, 7 critical differentiations between left versus right, and 6 critical descriptive terms (see Appendix E). The critical terms were determined based on the fewest number of terms needed to place the correct symbol in the correct place on the board given the differences in symbols to choose from and the stationary symbols on the board. For example, direction giving statement number 5 included the critical color “red” and the critical object “crayon,” as there were other red symbols to choose from, as well as other colors of crayons. When placing the red crayon on the board, it was decided that “roof” and “purple” were necessary, though “house” was not. This was because the crayon needed to be placed on the roof, and it needed to be the roof located on the purple object. House was not deemed a necessary term, because there was only one purple item located on the board.

The data were analyzed using a Chi-Squared Test of Independence. This non-parametric test is used to determine whether or not there is a significant association between two variables within a population. This test allowed determination of whether there was a statistically significant difference in the performance of the monolingual versus the bilingual children.

Results

The purpose of this study was to evaluate and compare the referential communication skills of bilingual and monolingual second graders. These skills were measured by counting the number of errors that occurred in the categories of various objects, positional terms, colors, left versus right, and descriptive terms.

Language test results

The Test of Language Development-Primary 4th Edition (Newcomer & Hammill, 2008) was used to determine if the language skills of the children were age appropriate. Subtest 1, Picture Vocabulary, and Subtest 4, Syntactic Understanding, were given to test each child’s receptive (listening) communication. Subtest 2, Relational Vocabulary, and Subtest 5, Sentence Imitation, were chosen to evaluate a child’s expressive (speaking) communication skills. Subtests 1 and 4 were added and the sum was converted to a Listening Index/Receptive score. Subtests 2 and 5 were added and the sum converted into an Organizing Index/Expressive score. All of the children scored in the average range for the expressive communication tasks. The monolingual children all scored within the average range for receptive communication, while four of the five bilingual children scored within the average range and one scored in the below average range (see Table 1). Although child one scored below average on the Listening Index/Receptive score, there was not a noticeable difference in direction giving and following performances.

Table 1

Test of Language Development-Primary 4th Edition

Ethnicity Listening Index/Receptivea

Organizing Index/ Expressiveb

Bilingual

Child 1

80c

111

Child 2

94

106

Child 3

91

109

Child 4

86

106

Child 5

86

86

Monolingual

Child 6

111

120

Child 7

114

117

Child 8

117

120

Child 9

111

117

Child 10

111

120

Note: a=Receptive includes Picture Vocabulary and Syntactic Understanding. b=Expressive includes Relational Vocabulary and Sentence imitation. c= a student whose score was 1.33 standard deviations below the mean of 100 with a standard deviation of 15.

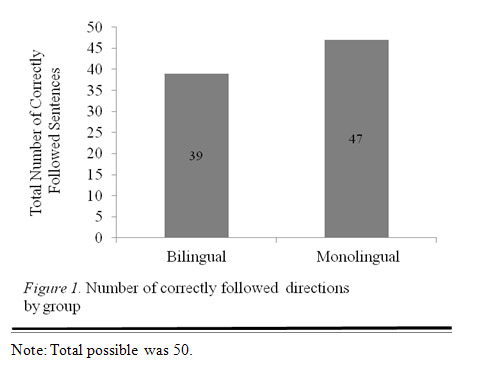

Direction Following ResultsEach child followed 10 directions (see Appendix C). The group of five bilingual children followed 39 of the 50 possible directions correctly (see Figure 1). Individual scores ranged from 6 to 10. Of the 11 errors, five were positional terms, three were left versus right errors, two were description terms, and one used an incorrect color. The five monolingual children followed 47 of the 50 possible directions correctly with a range of 8 to 10. The three errors consisted of one in each of the following categories: positional, left versus right, and descriptive terms. A Chi-Squared Test of Independence was used to determine that the performances of the bilingual and monolingual children were independent. This led to the assumption that there was a difference in the direction following skills of these two groups of children (p=.02). A review of the individual scores revealed that the one bilingual child who scored below average on the TOLD-4 had no more errors than the other bilingual children.

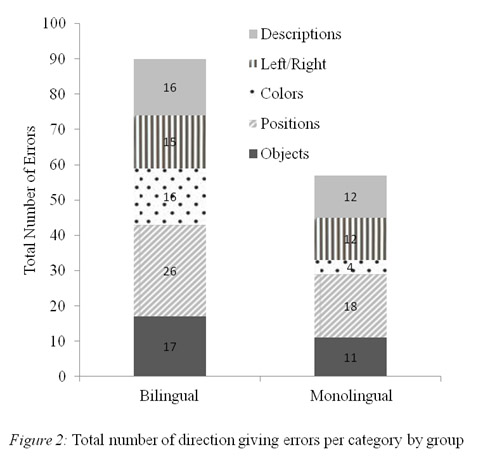

Direction Giving Results

The five bilingual children made a total of 90 errors in the five categories (see Figure 2). Each bilingual child averaged 18 total errors with a range of 9 errors to 29 errors (see Table 2). These children had the most difficulty with the positional terms, missing on average 5.2; however, they did the best differentiating between left and right. Of the 90 total errors made by the bilingual group, 80 of the errors were omissions of critical information (for example, stating to put the leaf under the pool, instead of the dark green leaf, as there was a dark and light leaf to choose from), while only 10 were errors in which the child gave an incorrect direction (for example stating to put it on the left side of the house instead of the right).

The monolingual children made a total of 57 errors (see Figure 2). Each monolingual child made an average of 11.4 errors (see Table 2). The range was 6 to 18 errors. These children also had the most difficulty with the positional terms, averaging 3.6 positional errors. Their strength was with colors, as they on average missed fewer than one per child. Of the 57 total errors for the monolingual group of five children, 3 were due to incorrect information, and 54 were omissions of necessary pieces of information.

The total number of errors per group was applied to a statistical “difference of two-proportions” test. At a 95 percent confidence level, there was a difference between the bilingual and monolingual children’s abilities. Visual inspection of the data revealed that the monolingual children made fewer errors than the bilingual children for every category (see Table 2). Given the small number of participants, it was not possible to determine whether these differences within categories were statistically significant.Note: a n= Total number of critical terms necessary.

Table 2

Average number of direction giving errors by group

Group

Categories

Bilingual

Monolingual

Objects (n=14)a

3.4

2.2

Positional (n=11)a

5.2

3.6

Colors (n=10)a

3.2

.8

Left/Right (n=7)a

3

2.4

Descriptive (n=6)a

3.2

2.4

Total (n=48)a

18

11.4

Although Table 2 allows for the comparison of the raw data between the two groups, it does not allow one to compare performance across categories. This is due to the different number of necessary terms in each of the categories. Therefore the data were recalculated by taking the average number of errors in a category divided by the total critical terms per category. For example, the monolingual children averaged 2.2 object errors and there were a total of 14 possible critical objects. 2.2 divided by 14 =.1571 (see Table 3). This allowed us to compare the children’s performances across categories. This revealed that even though the highest number of average errors for the monolinguals was in the category of positional terms (3.6) (see Table 2), they erred with only 32.7 percent of the positional terms. In comparison, they made a higher percentage of errors with descriptives (40%), even though Table 2 suggests they had fewer errors (2.4). Both groups made the greatest percentage of errors with descriptive terms. By viewing Table 3 it can also be seen that the largest difference between groups in percentage of errors was in the category of colors, and the smallest difference in the percentage of errors occurred in the objects and left/right categories.

Note: Percentages were calculated by taking the average number of errors for each group in each category divided by the total number of critical terms for that category.

Table 3

Percentage of total direction giving errors by category and by group

Group

Categories

Bilingual

Monolingual

Percent Difference

Objects

.2429

.1571

.0858

Positional

.4727

.3273

.1454

Colors

.3200

.0800

.2400

Left/Right

.4286

.3429

.0857

Descriptive

.5333

.4000

.1333

Across categories

.3750

.2375

.1375

The number of critical elements that were required for each direction had an impact on the children’s performance (see Table 4). When at least three critical elements were required, the group of bilinguals were accurate 32/50 (64%) of the time, while the group of monolinguals were accurate 44/50 (88%) of the time. When at least four critical elements were required, the bilinguals were accurate 19/45 (42%) of the time, while the monolinguals were accurate 25/45 (56%) of the time. When at least five critical elements were required, the bilinguals were accurate 9/25 (36%) of the time, and the monolinguals were accurate 13/25 (52%) of the time. When at least six critical elements were required, the bilingual children were accurate 2/15 (13%) of the time, and the monolingual children were accurate 3/15 (20%) of the time. When the researchers looked at these numbers, it was found that all of the children did better with fewer critical elements per direction. The monolinguals were accurate at least half of the time when 3, 4, or 5 elements were required, while the bilinguals were only 50 percent correct with three elements. This finding suggests that the difference between the two groups may be due to the number of critical elements per direction and that the bilingual children’s difficulty was because of the number of elements that had to be included at one time.

Note: Number of critical elements required is in parentheses.

Table 4

Number of critical elements correct for each direction given

Group

Child

Direction number

1

(3)2

(5)3

(5)4

(4)5

(4)6

(7)7

(6)8

(6)9

(4)10

(4)Bilingual

1

3

2

2

1

0

2

3

3

1

2

2

3

3

5

3

4

5

5

4

2

4

3

3

3

4

4

3

6

5

6

4

4

4

3

5

3

3

4

5

5

4

1

2

5

3

2

2

2

1

4

1

1

0

2

Monolingual

1

3

3

5

3

3

5

6

6

4

4

2

3

4

3

3

3

4

2

3

3

3

3

3

5

5

3

4

5

6

5

3

3

4

3

1

2

4

2

4

4

2

3

4

5

3

5

5

4

4

5

5

4

2

3

Discussion

This study did not support the hypothesis that bilingual children would perform better on referential communication tasks. In fact, the monolingual children did significantly better than the bilinguals at the direction giving and following tasks.

Direction Following Task

In the direction following portion of the barrier activity, the bilinguals had a total of 11 errors while the monolinguals had 3 errors. Of the errors made by the bilingual children five were positional, three were left versus right, two were descriptions, and one was an incorrect color. The monolingual children as a group made one error in each of the following categories: positional, left versus right, and descriptive terms. This was determined to be a significant difference through use of the Chi-Squared Test of Independence. The small number of direction following errors made determination of the reasons difficult. However, given that all children followed three of the four directions (direction numbers 1, 5, and 10) with the fewest number of words (9, 9, and 7 respectively) correctly, one might conclude that number of words affected accuracy. However, direction number 6 was also followed correctly by all children and it was the longest direction, containing 28 words. Another possibility is that a combination of length (number of words) and complexity (number of clauses and prepositional phrases) determined accuracy. Utterances 1, 5, and 10 were all simple statements with only one or two prepositional phrases. But again, number 6, with three clauses and four prepositional phrases, does not fit this hypothesis.

All of the children did very well with the direction following task considering the number of critical elements in each direction. Four children made no errors at all. Because most children, including the one child with the lowest TOLD-4 score, only made one error for any one direction (e.g., “on” for “above” and “right” for “left”), it is most likely that each child did not listen carefully enough or remember all the words well enough to follow all directions perfectly.

Direction Giving Task

In the direction giving task, the monolingual children also did significantly better with 57 errors compared to the bilingual children’s 90 errors out of a possible 240 critical terms. The largest group difference was in the category of colors, where bilingual children made errors 32 percent of the time compared to the monolinguals’ 8 percent. During the direction giving task, the groups were most similar in their accuracy and inclusion of objects and left versus right terms. Research supports this developmental difference as children typically find learning color terms to be a more difficult linguistic task than learning terms for objects (Pitchford, 2006).

General Comments

Before the children started the barrier activity the names of objects as well as directional terms were discussed to ensure that vocabulary did not account for the difference in the children. This suggests the participants had the semantic knowledge needed to perform the task. The fact that the bilingual children used incorrect terms (right/left) only ten times supports this idea. This information, along with the expressive scores from the TOLD-P 4th Edition that involved both semantic and syntactic skills, suggests that the difficulties the bilingual children had were not semantic or syntactic. However, the children made no object term errors when following directions but did make object term errors when giving directions. This supports a common finding that children perform better with receptive tasks than expressive ones (Pena, Bedore, & Rappazzo, 2003).

Pragmatics is the knowledge of what is socially appropriate use of a language. The bilingual children struggled with knowing when to use a specific term or how much information was needed in order to properly recreate the photograph. This was evidenced by their omission of 80 critical elements.

The barrier activity in which the children participated was a verbal task in which a child gave and followed directions much like they would encounter in daily social life. As stated by Estrada, et al. (2009), it may take two to three years of immersion in a second language for a child to become proficient at basic interpersonal communication skills. The results of this study suggest that referential communication may be more of an academic task than a social communication task. It can take up to five or seven years for the child to reach cognitive academic language proficiency. The bilingual children were judged to be fluent in English by their teachers, although they had not had the five to seven years of instruction required to become proficient enough to receive academic instruction in their second language.

The most likely explanations for the differences found between our groups of monolingual and bilingual children on this referential communication task were suggested by Meyer (2000). She proposed that English learners experience a “language load” when instruction is provided in a child’s nonnative language. Even though a child may have adequate language skills for conversational use, they may not have academic language proficiency. Fillmore (as cited in Meyer, 2000) suggested that teachers must explicitly teach these language terms and patterns within classroom lessons and use them repeatedly as the teacher teaches. Meyer also proposed that English learners experience a “learning load.” This relates more to the context in which children are expected to demonstrate their language proficiency. Even though her example of a classroom activity with high learning load was brainstorming, with its fast pace and lack of visual support, referential communication may also present a learning load challenge. The pace of a barrier task is slower (and it does include visual support), but it places high expectations on participants to use language in terms of the number of elements to be communicated accurately because if one misses any of those elements the task will not be accomplished perfectly.

There is no way to ascertain for sure the most significant reason for the bilingual children’s difficulty with the direction giving and following tasks compared to that of the monolinguals. After analyzing the data described previously, the difference cannot be based solely on vocabulary knowledge or syntax but rather on the number of critical elements in the directions and on combining the information to determine what information was necessary for clear, concise communication to a partner. It is possible that the performance of these two groups of children differed because of a combination of the skills discussed above.

Limitations

There are several limitations of this study. One is due to the small sample size. A study that involved a larger sample might provide stronger or different evidence of the bilingual children’s referential communication skills. Also, the study used a teacher questionnaire to determine English fluency, rather than a formal assessment of their English skills. In addition, the age at which the children began speaking English was unknown to the researchers. The children likely began formal English education once they started kindergarten, although they may have begun learning English at an earlier age. The language spoken in the homes of the bilingual children as well as the education levels and socioeconomic status of the parents were unknown. These factors may have had an effect on the English proficiency of the children.

Implications

If, as Bunce (1991) suggested, children who have difficulty using referential communication skills are at a real disadvantage in the classroom, these bilingual children may benefit from classroom instruction and practice in giving and following directions of increasing lengths and complexities, thus enhancing receptive and expressive communication skills vital to academic success. So, even though these children are probably still developing this skill, they may be getting further and further behind compared to their monolingual peers. This could, in part, account for the disparity in academic performance between monolingual and bilingual children in English-speaking classrooms.

Pragmatic, and specifically referential communication, skills are important for activities in the classroom and more emphasis may need to be placed on their development. Pragmatics is a skill that is difficult to test and there are few good standardized pragmatic tests available. It is a skill that is often judged based solely on observation or interview, both measures being somewhat subjective. A child’s pragmatic skills should be carefully evaluated and not assumed to be fully developed once a child is considered fluent in his/her second language at a conversational level. Even though a child appears to follow verbal directions, he/she may have much more difficulty giving directions. This is an important classroom skill, yet this expressive skill is challenging to do well, especially for English language learners. Another caution is to be careful of inferring expressive language use from a child’s level of receptive language. As this task demonstrated, children can “know” vocabulary and concepts but not be equally proficient in using them.

The results of this study support Meyer’s (2000) language load theory in that even though our bilingual children were judged to be fluent in conversational English, they performed these barrier tasks below the level of their monolingual peers. This study also supported Estrada et al. (2009) as we suspect that our bilingual students have not had the five to seven years of English immersion to reach the cognitive academic language proficiency required for referential communication. Individuals who provide academic instruction to bilingual students should be cautious in assuming English proficiency and readiness for instruction in English based on social use of the language.

References

Ben-Zeev, S. (1977). The influence of bilingualism on cognitive strategy and cognitive development. Child Development, 48(3), 1009-1018. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.ep10403617.

Bialystok, E. (2010). Global–local and trail-making tasks by monolingual and bilingual children: Beyond inhibition. Developmental Psychology, 46(1), 93-105. doi:10.1037/a0015466.

Bowman, S. (1984). A review of referential communication skills. Australian Journal of Human Communication Disorders, 12, 92-112.

Brock, C.A. (1986). The effects of referential questions on ESL classroom discourse. TESOL Quarterly, 20(1), 47-59. Retrieved from JSTOR database.

Bunce, B. H. (1989). Using a barrier game format to improve children’s referential communication skills. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 54, 33-43.

Bunce, B. H. (1991). Referential communication skills: Guidelines for therapy. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 22, 296-301.

Carlson, S., & Meltzoff, A. (2008). Bilingual experience and executive functioning in young children. Developmental Science, 11(2), 282-298. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7687.2008.00675.x.

Chamot, A.U. (1983). Toward a functional ESL curriculum in the elementary school. TESOL Quarterly, 17(2) 459-471, Retrieved from JSTOR Database.

Estrada, V., Gómez, L., & Ruiz-Escalante, J. (2009). Let's make dual language the norm. Educational Leadership, 66(7), 54-58. Retrieved from Professional Development Collection database.

Frymier, A., & Houser, M. (2000). The teacher-student relationship as an interpersonal relationship. Communication Education, 49(3), 207-219. Retrieved from Communication & Mass Media Complete database.

Meshoulam, U. (1981). The role of language skills in referential communication. Journal of Genetic Psychology, 139(1), 151-152. Retrieved from Academic Search Complete database.

Meyer, L. M. (2000). Barriers to meaningful instruction for English learners. Theory into Practice, 39 (4). 228-236.

Newcomer, P. L. & Hammill, D. D. (2008). Test of language development: Primary 4th edition. Pro-ed: Austin, TX.

Oller, J. W. (2005). Common ground between form and content: The pragmatic solution to the bootstrapping problem. Modern Language Journal, 89(1), 92-114. doi: 10.1111/j.0026-7902.2005.00267.x

Owens, R. E. (2008). Language Development: An Introduction. Geneseo, New York: State University.

Pena, E., Bedore, L. M., & Rappazzo, C. (2003). Comparison of Spanish, English, and bilingual children’s performance across semantic tasks. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 34(1), 5-16. Retrieved from EBSCOhost Academic Search Complete database.

Pitchford, N. J. (2006). Reflections on how color term acquisition is constrained. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 94(4), 328-333.

Preston, J. M. (1984). Referential communication: Some factors influencing communication efficiency. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 16(3), 196-207. doi: 10.1037/h0080839

Rubin, K. H. (1972). Relationship between egocentric communication and popularity among peers. Developmental Psychology, 7(3), 364.

Solari, E. J., & Gerber, M. M. (2008). Early comprehension instruction for Spanish-speaking English language learners: Teaching text-level reading skills while maintaining effects on word-level skills. Learning Disabilities Research, 23(4), 155-168.

Sonnenschein, S., & Whitehurst, G. J. (1984). Developing referential communication: A hierarchy of skills. Child Development, 55, 1936-1945.

Appendix A

Graphic Symbols Used in Barrier Task

Appendix B

Town Setting Board Used in Barrier Task

Appendix C

Direction Following Statements Given to the Children

- Put the apple in the middle of the pool.

- Put the soccer ball on the blue house in the lower right corner of the board.

- Put the flower with the white petals on the right side of the purple house.

- Put the blue star on the right side of the pink house that’s in the upper left hand corner.

- Put the dark green leaf below the basketball court.

- Put the big basketball on the road that goes up and down closest to the blue house that’s in the middle on the bottom of the board.

- Put the red white and blue star on the roof of the pink house closest to the pool.

- Put the big solid red arrow pointing upwards on the road between the pool and the basketball court.

- Put the yellow crayon above the blue house with the shorter black roof.

- Put the heart on the basketball court.

Appendix D

Pattern Given to Children for Giving Directions

Appendix E

Critical Concepts for Direction Giving Activity

Key: Objects, Positions Color, LEFT/RIGHT, Descriptions

- Put the soccer ball on the basketball court.

- Put the yellow star on the road that goes sideways, right beneath the basketball court.

- Put the apple on the bottom RIGHT corner of the pink house that is on the LEFT.

- Put the red, white, and blue star on the LEFT side of the pink house that is on the LEFT.

- Put the red crayon on the roof of the purple house.

- Put the smaller, patterned red arrow pointing up, on the blue house with the shorter black roof.

- Put the big, solid, red arrow pointing downwards in the pool.

- Put the purple flower on the top LEFT corner of the pink house that is closer to the pool.

- Put the dark green leaf below the pink house in the top RIGHT corner.

- Put the yellow crayon on the bottom RIGHT corner of the board.

|