A Study of Attendees’ Motivations: Oxford Film Festival

Taylor Thomas

Young Hoon Kim*

Abstract

The purpose of this study was to explore the motivations of attendees at the Oxford Film Festival, held in Oxford, MS. One hundred nine surveys were collected, and factor analysis was used to group 10 individual motivators into 3 factors. The three factors were Togetherness in Good Environments, Money, and Film Itself.

Keywords: Film Festival, Attendees’ Motivations, Festivals, and Events

Introduction

Festivals play a significant role for communities by attracting tourists, creating positive economic impact, creating opportunities for community involvement and togetherness, and enhancing the image of the destination. Festivals and special events have grown in all destinations and are the fastest growing segment of the tourism field (Park, Reisinger, & Kang, 2008). Special interests in festivals and events such as cultural preservation, experiencing local foods and cultures, and community involvement in a destination have led to an increased emphasis on regional and local festivals. According to the Historic/Cultural Traveler (2003), approximately 41 percent of travelers attended a festival and/or fair during their travel. A number of studies have been conducted on festivals and events with their many advantages for communities (Getz, 1993). However, many festivals are still in the early stage in both practical management and theoretical study, particularly film festivals which have increased each year leading to more attention being paid by destination marketing organizers and researchers.

Kim, Goh, and Juan (2010) stated that it was widely accepted that understanding travel motivations is vital in predicting future travel patterns. According to Park, Reisinger, and Kang (2008), understanding consumers’ motivations is a key prerequisite to creating desirable experiences and satisfaction for customers. By understanding tourists’ motivations, their needs can be fulfilled through marketing activities (Xie, Costa, & Morais, 2008). Fodness (1994) also stated that effective marketing is impossible without indentifying, understanding, and prioritizing consumers’ motivation. Increasing interest and more involvement in festivals has contributed to the growth of festivals. However, little attention has been paid to film festivals and especially to attendee’s motivation.

A film festival, which is held annually in Oxford, Mississippi, was selected for this study. The data were collected at the seventh year of the Oxford Film Festival in 2010. The primary purpose of this study was to investigate attendees’ motivations at a film festival. The factor analysis method was employed to reduce variables and put them together with similar variables. A factor extraction was conducted through Principle Component Analysis (PCA), and factor rotation was performed through the Varimax with Kaiser Normalization. Also, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was used to evaluate the reliability of scales. This study provided festival organizers with valuable information concerning the motivations of festival attendees. The results showed that attendees were motivated by a desire to attend a festival with quality films that could be enjoyed in a good environment.

Literature Review

Festivals and Destination Management

Festivals have been recognized as one of the most important areas of the tourism industry, and they have contributed to their host communities in a number of ways: creating economic impact, enhancing the overall image of the destination, and creating community involvement. Festivals have also provided the community with the recognition of the destination. According to Grunwell, Ha, and Martin (2008), festivals could bring a whole new group of tourists to a destination. When visitors have a positive experience in the host community, they will return to that destination in the future (Woosnam, McElroy, & Winkle, 2009).

One of the most distinguished characteristics of festivals is their ability to create high returns on small investments (Getz, 1993). One way that festivals create less financial responsibilities for themselves is by holding events in temporary or already existing physical locations (Gursory, Kim, & Uysal, 2004). Most festivals do not own permanent physical structures that are a constant financial burden. Additionally, many festivals are managed and operated by a small staff or volunteers (Gursoy, Kim, & Uysal, 2004), which is beneficial for both the residents and the festival. Residents benefit by being able to stay active in their community, and the festival benefits from a labor force that does not require much monetary compensation. These characteristics make festivals more tolerant of economic downturns. This resistance to poor economic environments makes festivals more attractive to communities or organizations looking to start a new project.

Festivals provide an opportunity for residents and businesses of the local community to get involved and become active participants in their community. The ability of festivals to involve members of the host community gives festivals an important role in the preservation of a community’s culture. During festivals, an atmosphere is created with valuable and cultural ideas, practices, and traditions that can be shared with others. New members of a community can learn about a community’s culture from festivals conducted by the hosting community. Festival events create a sense of community and cohesiveness among community members (Gursoy, Kim, & Uysal, 2004). Festivals can celebrate the music, art, food, film, or countless other aspects of a community’s culture and heritage. Thus, festivals are ideal projects for developing unique aspects of the community’s culture. A sense of pride is developed as a community celebrates together. This pride and excitement from the host community can be important factors in attracting non-resident tourists to a festival as well as in providing a great opportunity for residents to be involved in community events. According to Lee, Lee, and Wicks (2004), festivals enhance tourists’ experiences by using the local community’s culture to create a unique experience.

Film Festivals

According to Bauman (2001), film festivals are one of the youngest segments of the different types of festivals because of one major reason: the history of film making is just over 100 years. The first film festival, the Columbus International Film and Video Festival, was founded in 1953. Film festivals were created as competitive events in which the winners were bestowed with a widely accepted artistic merit that many films did not have. As a major impact on the film business, cinema began in the 1890’s and by 1950 approximately 22,000 films had been produced in the United States. In 1958, the San Francisco Film Festival began, followed by the New York Film Festival in 1963, the Chicago International Film Festival in 1965, the Seattle International Film Festival in 1974, and the Boston Film Festival in 1985, respectively. Countless other film festivals occurred in between each of those (Baumann, 2001). There are numerous film festivals that happen each year around the world, and new ones are added every year.

The first film festival was held for the purpose of showing films as an event for the film industry. Attendees at the film festivals were comprised of filmmakers, actors, crews, producers, directors, distributors, and people directly related to the films. The creation of film festivals helped spark growth in the world of film. The film industry grew along with a rapid increase in the number of film festivals. Film festivals created a place where filmmakers could meet producers and distributors and find possible ways for their movies to be produced on a large scale (Baumann, 2001). As a result of the increasing numbers and popularity, festivals grew into bigger events that also included the general public. Film festivals began to include films of all types: student and professional competitions, seminars with film industry professionals, workshops on many aspects of the film industry, technical exhibits, tours of locations, and gala events (Grunwell, Ha, & Martin 2008).

Although film festivals became more open and attractive to the general public, most film festivals attract a small niche of tourists compared to other kinds of festivals (Grunwell, Ha, & Martin 2008). With limited physical spaces and a smaller niche market to attract, film festivals can still create large positive effects on host communities. Film festivals are frequently held outside of a destination’s normal tourism season (Grunwell, Ha, & Martin 2008). This fact positively impacts the host community by bringing in tourists during a typically “down” time of the year. Even with the many advantages and merits of film festivals, only a few studies have been conducted on the demographics and behaviors of attendees at film festivals.

Grunwell, Ha, & Martin (2008) examined attendees’ behavior and their characteristics at the Asheville Film Festival. They found that the economic impact per person at the film festival was greater than that of the attendees at a regional street festival also held in Asheville, Tennessee. A study by the European Coordination of Film Festivals in 1999 also showed that attendees at film festivals spent more money per person than attendees at other types of festivals. The European Coordination of Film Festivals’ study showed that film festival attendees have a higher income and education level than attendees at other kinds of festivals. More importantly, Grunwell, Ha, & Martin (2008) found that the environmental impact of the film festival was much more positive than that of the street festival.

Film festivals do not typically cause an increase in traffic and safety hazards or produce other negative environmental impacts on a host community. Ecotourism or “green tourism” has become important recently. In order to understand the advantages of film festivals, Bergin-Seers and Mair (2009) conducted a study to create a measurement tool of the “greenness” of tourists. Although the tool could not provide enough range to measure the levels of “greenness,” the study still indicated that tourists were concerned with environmental issues. More studies are being conducted to find correlations between tourists’ level of “greenness” and their purchasing decisions.

Motivations

Numerous studies have been conducted on tourists’ motivations, and it is widely accepted that tourists’ motivations play an important role in tourism planning and marketing (Backman, Backman, Uysal, & Sunshine, 1995; Kim, Goh, & Yuan, 2010; Lee, 2000; Lee, Lee, & Wicks, 2004; Park, Reisinger, & Kang 2008; Uysal, Gahan, & Martin, 1993; Schneider & Backman 1996). In this connection, motivation is defined as something that leads to an action that fulfills a need (Goossens, 2000). Human beings have many needs and constantly seek a balance of what is needed and what is already obtained (Crompton, 1979). The following factors influence human needs: demographic, geographic, socioeconomic, cultural, physical, and psychological. Therefore, most tourism operations or organizations seek to create tourism products or services that fulfill the needs of tourists. A number of previous festival studies showed that finding attendees’ or tourists’ motivations for a specific theme or type of festival is a very critical step in successful planning and executing of a festival (Uysal, Gahan, & Martin, 1993; Mohr, Backman, Gahan, & Backman, 1993; Backman, Backman, Uysal, & Sunshine, 1995; Scott, 1996; Formica & Uysal, 1996; Formica & Uysal 1998; Schneider & Backman 1996; Crompton & McKay, 1997; and Lee, 2000).

Yoon and Uysal (2005) proposed a model to indicate an ideal process towards destination loyalty. The model was based on consumer motivations, and it showed that knowledge and understanding of consumer motivations might ultimately help in capturing consumer destination loyalty. It is festival loyalty that organizers seek because it creates repeat visitors who are vital to the success of any operation (Petrick, 2004). A common business strategy is to separate potential visitors into segments. Once visitors are separated, specific targeting can be used to market tourism products to each segment. Knowing the motivations of each segment aids festivals in meeting the needs of each and every visitor, which in turn lead to repeat customers.

Several studies have been conducted to find a simple and standard way of measuring and comparing tourists’ motivations. Dann (1981) and Crompton (1979) developed a way to measure motivations using push and pull factors. Push factors come from within an individual and affect the desire to travel. Pull factors are things outside of the individual and deal more with choosing a specific destination after the desire to travel has already been established by the push factors. Push factors include desires to escape everyday life or to find new adventures, and pull factors include destination attractions such as lodging, food, and entertainment.

Iso-Ahola (1982, 1989) developed a framework by which motivations could be categorized and measured. His model is based on two types of motivations: seeking and escaping. Seeking and escaping are further categorized as personal and interpersonal. Tourists seek personally to find knowledge and new ideas or seek interpersonally to create new friendships and bonds with others. Tourists can also be motivated by needs to escape, either personally from their own anxieties and stresses or interpersonally from problems dealing with other people. These findings tie into the belief that humans are constantly struggling to find a balance between too much and too little stimuli. When a person is experiencing too much stimuli in life they will have a need to escape, whereas a person looking for stimuli will seek out new opportunities and knowledge.

Maslow (1954) provided one of the most important theories for motivation: the Hierarchy Theory of Needs. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs is a pyramid structure that puts human motivations into five categories with the most important and most basic at the bottom. The category in the lowest level is physiological needs including basic human needs such as food and shelter. The next level is safety, which plays into human’s tendencies to avoid the unknown. For the next upper level from safety, socialization is addressed, referring to human needs for relations with other humans, followed by ego and finally self-fulfillment. Self-fulfillment is related to human needs for growth in cognitive and aesthetic aspects. Cognitive growth includes areas such as gaining knowledge and understanding while aesthetic growth refers to a constant search for beauty and balance in the world.

Most tools used to measure motivations look at specific dimensions of motivations rather than just the overall motivation (Lee, Lee, & Wicks, 2004). Over the last two decades, studies have found a number of important dimensions of motivation factors of tourists and attendees at different festival events (Uysal, Gahan, & Martin, 1993; Mohr, Backman, Gahan, & Backman, 1993; Backman, Backman, Uysal, & Sunshine, 1995; Scott, 1996; Formica & Uysal, 1996; Formica & Uysal 1998; Schneider & Backman 1996; Crompton & McKay, 1997; and Lee, 2000). Those studies emphasized that these categories of motivations must be considered to understand festival attendees’ behavior: e.g., escape, excitement, novelty (novelty/regression), socialization/family togetherness (gregariousness), nature appreciation, curiosity, cultural/historical, festival attributes, and recovering equilibrium.

Methodology

Study Site

This study was conducted at the Oxford Film Festival in Oxford, MS, a destination known for a strong artistic community based in its literary roots. Bill Thomas from the Washington Post (2010) also described Oxford’s literary roots this way:

Oxford also occupies a unique place in American literary history. William Faulkner lived here for most of his life, using the town as a setting for many of his novels and short stories. Willie Morris, whose own work explores the strange hold his native state has on Mississippians, wrote that Faulkner's "physical and emotional fidelity to Oxford ... was at the core of his being, so that today Oxford [is] the most tangibly connected to one writer's soul of any locale in America." In addition to Morris, who lived here for years before his death in 1999, the town has been home to dozens of authors, including John Grisham, Barry Hannah, Larry Brown and Richard Ford. (p. 1)

The 7th annual Oxford Film Festival was held Thursday, February 4 through Sunday, February 7, 2010. Between 55 and 75 films are shown at the event each year. Many types of films are accepted into the festival including: animation, documentary feature and short, experimental, and narrative feature and short. Films are shown in both competitive and showcase settings. Although the showing of films is the major purpose of a film festival, the festival also includes panel discussions with film industry professionals, social events, and children’s activities.

Instrument and Motivation Measurements

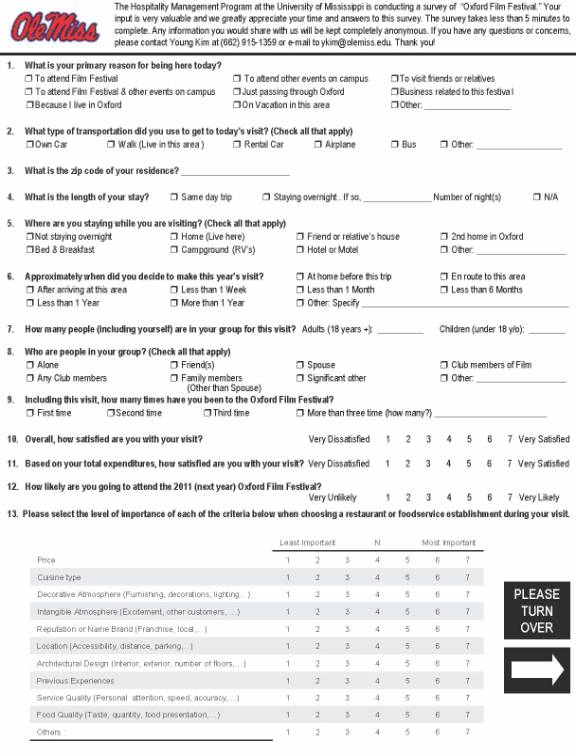

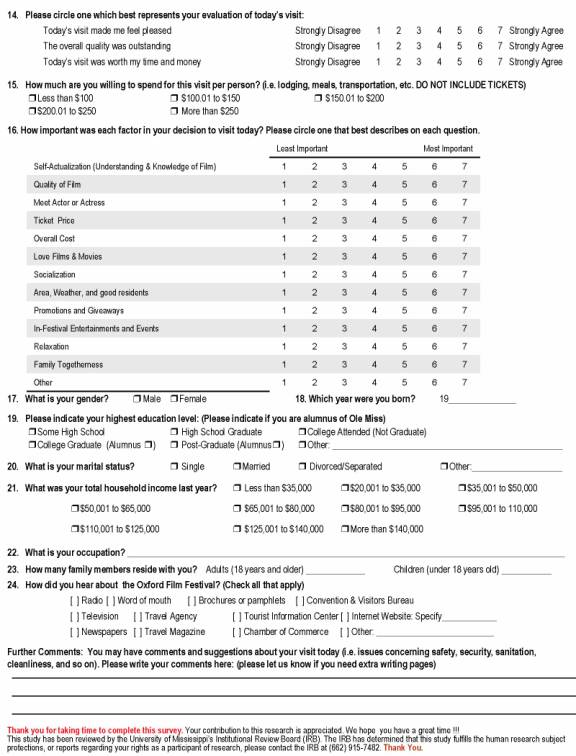

The instrument for this study was designed to measure the motivations of attendees at the Oxford Film Festival. Based on a previous study (Kim et al., 2010), the literature review was performed to develop the twelve motivational factors included on the instrument. The twelve factors were chosen and refined specifically for the film festival. Using undergraduate and graduate students, a pilot test was conducted to establish reliability. Experts in tourism research and in film and festivals also reviewed a draft of the instrument to determine validity. Comments and inputs were used for development of the final instrument.

The final instrument was a two-page survey consisting of twenty-four items, divided into three sections: socio-demographics, travel arrangements and accommodations, and festival motivations. The twelve motivation factors included self-actualization (understanding & knowledge of film), quality of film, meet actor or actress, ticket price, overall costs, loves films and movies, socialization, area weather and good residents, promotions and giveaways, in-festival entertainment and events, relaxation, and family togetherness. Attendees were asked to rank the level of importance of each factor on a 7 point Likert scale, from “(1) least important” to “(7) most important.”

Data Collection and Analysis

Data were collected at the Oxford Film Festival on Friday evening, Saturday evening, and Sunday afternoon. Five CITI (Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative) certified research assistants from the University of Mississippi administered and collected the surveys under the supervision of an academic researcher. Attendees were randomly approached and the purpose of the study was explained. They were then invited to participate; only those who said “yes” were administered a survey. Attendees completed the survey in front of the research assistants, and the surveys were checked briefly and collected immediately after completion. Each participant was given a raffle ticket and entered into a drawing for a pass to the 2011 Oxford Film Festival. A total of 113 attendees agreed to complete the questionnaire. The statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS 15.0 for Windows) was used for data analysis. After encoding data in SPSS, the data were screened for usability. Descriptive statistics were used to represent the sample, and factor analysis was used for item elimination.

Results

Two questionnaires were eliminated from the analysis because substantial sections were not completed correctly and two other questionnaires were eliminated because respondents marked the same ratings on consecutive questions. A total of 109 useable surveys were collected. Table 2 shows the summary of attendees’ socio-demographics.

Table 2. Attendees’ Socio-demographics

Frequency

Percentage (%)

Age (n=86)

18-27

40

47

28-37

22

26

38-47

9

10

48-57

9

10

58 and older

6

7

Gender (n=109)

Male

52

47.7

Female

57

52.3

Education (n=109)

Some high school graduate

2

1.5

High school graduate

6

6

Some college graduate

39

36

College graduate

28

26

Post-graduate

32

29

Other

2

1.5

Marital Status (n=93)

Single

65

70

Married

22

24

Divorced/Separated

3

3

Other

3

3

Annual Household Income (n=99)

< $20,000

34

34

$20,001 - $35,000

17

17

$35,001 - $50,000

9

9

$50,001 - $65,000

7

7

$65,001 - $80,000

5

5

$80,001 - $95,000

3

3

$95,001 - $110,000

8

8

$110,001 - $125,000

3

3

$125,001 - $140,000

1

1

> $140,000

12

12

Spending per Person (n=101)

< $100

69

68

$100.01 - $150

14

14

$150.01 - $200

10

10

$200.01 - $250

7

17

> $250

1

1

Female attendance (52.3%) was a little higher than male attendance (47.7%). The largest age group of attendees ranged from 18 to 27 (47%), reflecting the large student population that is one of the main characteristics of a college town. Thirty-six percent of respondents reported that they had earned some college degrees followed by post-graduates (29%). About thirty-four percent of respondents reported an annual income of $20,000 or less. On the other hand, approximately twelve percent of respondents reported that they earned more than $140,000 per year. More than two thirds of attendees were single (70%) and about sixty-eight percent of attendees were willing to spend less than $100 per person for their visit. Festival attendees were mostly residents of Oxford, MS (67%), which led to lower spending per person due to less need for travel arrangements and accommodations.

Table 3. Factor Loading and Communality

Factors

Attributes

Factor Loadings

Communality

Eigen-Value

Variance (%)

Reliability Coefficient

Factor 1: Togetherness in Good Environments

In-Festival Entertainments and Events

.80

.67

2.81

28.13

.77

Family Togetherness

.71

.53

Relaxation

.69

.49

Area, Weather, and Good Residents

.63

.43

Promotions and Giveaways

.63

.56

Socialization

.62

.51

Factor 2: Money

Overall Costs

.92

.89

1.92

19.18

.90

Ticket Price

.90

.82

Factor 3: Film Itself

Quality of Films

.84

.75

1.58

15.79

.68

Self-Actualization

.81

.67

Table 3 shows the results of factor analysis. After Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA), the 3rd, 6th, and 13th items were eliminated. The 13th item (others) was eliminated because of its low response rate. Later, the 3rd item (meeting actors/actresses) was eliminated because the mean score was low and it was unrelated to the other items: items 1 and 2 (Costs and Price). Finally, the 6th item (love films & movies) was eliminated in order to have a higher Cronbach’s Alpha for Factor 3: Film Itself.

The question was asked, “How important was each motivation in your decision to visit today? Please circle one that best describes each question.” The results of factor analysis formed three factors: Togetherness in Good Environments, Money, and Film Itself.

Factor 1 included six attributes and had a reliability of .77. Factor 1 included the following: In-Festival Entertainments and Events; Family Togetherness; Relaxation; Area, Weather, and Good Residents; Promotions and Giveaways; and Socialization and accounted for 28.13 percent of the total variance. The attributes of factor 1 suggest that attendees were looking for enjoyable entertainment at the film festival where they could socialize with family and friends in a relaxing environment. Factor 2 was named Money. The two attributes of Factor 2 were Overall Costs and Ticket Price and it explained 19.18 percent of the total variance with a reliability of .90. With a reliability of .68, the two attributes of Factor 3, Quality of Films and Self Actualization (Film Itself) contributed 15.79 percent of the total variance.

Table 4. Mean Scores and Standard Deviation

Table 4 shows the mean and standard deviation scores of the 10 motivators as single items. Motivator 2: Quality of Film has the highest score (mean = 5.52) showing that the attendees were very concerned with the quality of films being shown at the festival. This can be compared to research findings at other types of festivals. Kim et. al. (2010) found that the single most important motivator for attendees at a food festival was Quality of Food. Promotions & Giveaways was ranked as the least motivator with the lowest score (mean = 3.11).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate the motivation factors of film festival attendees. The results suggested that factor 1, Togetherness in Good Environments, explained most of attendees’ motivations to attend the film festival, which is similar to the results of previous studies (Nicholson & Pearce, 2001; Yoon & Uysal, 2005). It was also found that Quality of Film was the most important motivator as a single item. This is similar to findings in studies done on other types of festivals. Kim et. al. (2010) found that the most important motivator for attendees at a food festival was Quality of Food.

An interesting comment from one of the attendees brought importance to the opportunity to see films on social issues. As characterized by their population, an educated group, they are more likely to show their interests and desires for social issues than other specific topics. These desires and interests are not only related to factor 3, Film Itself, but also to factor 1, Togetherness in Good Environments. The interests and desires to view films on social issues include the desire to discuss attendees’ reactions to the films. Although most film festivals provide some kind of after-sessions, they are typically more of a panel discussion with brief audience interaction. Film festivals could benefit greatly by creating events within the festival that facilitate discussion between attendees.

This study provided an initial investigation of the film festival attendees’ behavior, especially their motivations. The results also provided a profile of film festival attendees’ characteristics in a small film festival that will be very useful for both film organizers and destination marketing directors. Although the results of the current study may not be generalized beyond the attendees at the particular film festival, it is still valuable in findings and suggestions.

Limitations and Future Study

There were several limitations that may have affected the processes and results of this study. Because the study included only one film festival, the results may not be generalized to other areas. In addition, limitations may be associated with the measurement questions and tools. Although the modified scale was adapted from the literature review and other empirical studies, it may need more refinement.

Future research is planned to compare attendees of differing types of festivals such as arts, food, and film festivals and sporting events that are held in the same geographic area. Researchers hope to gain more knowledge by comparing results from these activities. The destination will benefit by knowing which festival is contributing the most to attraction of visitors, economic impact, and opportunities for community involvement and togetherness. For future study, the examination of factors such as attendees’ perceived value, satisfaction, intent to revisit, and expenditures could provide valuable information to festival organizers and destination marketers.

References

Backman, K. F., Backman, S. J., Uysal, M., & Sunshine, K. M. (1995). Event tourism: An examination of motivations and activities. Festival Management & Event Tourism, 3(1), 15-24.

Bauman, S. (2001). Intellectualization and art world development: Film in the United States. American Sociological Review, 66(3), 404-426.

Bergin-Seers, S., & Mair, J. (2009). Emerging green tourists in Australia: Their behaviors and attitudes. Tourism & Hospitality Research, 10, 109-119.

Crompton, J. L., & McKay, S.L. (1997). Motives of visitors attending festival events. Annals of Tourism Research, 6(4), 425-439.

Crompton, J. L., & McKay, S.L. (1997). Motives of visitors attending festival events. Annals of Tourism Research, 6(4), 425-439.

Dann, G. M. (1981). Tourism Motivations: An appraisal. Annals of Tourism Research, 8(2), 189–219.

European Coordination of Film Festivals. (1999). The socioeconomic impact of film festivals in Europe. Belgium: European Coordination of Film Festivals.

Fodness, D. (1994). Measuring tourism motivation. Annals of Tourism Research, 21(3),555-581.

Formica, S., & Uysal, M. (1996). A market segmentation of festival visitors, Umbria jazz festival in Italy. Festival management and event tourism, 3, 175-182.

Formica, S., & Uysal, M. (1998). Market segmentation of an international cultural-historical event in Italy. Journal of travel research, 36, 16-24.

Getz, D. (1993). Festivals, special events. In M. A. Khan, M. D. Olsen, & T. Var (Eds.), Encyclopedia of hospitality and tourism (pp. 789-810). New York, NY: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

Getz, D. (2008). Event tourism: Definition, evolution, and research. Tourism Management, 29(3), 403-428.

Goossens, C. (2000). Tourism information and pleasure motivation. Annals of Tourism Research, 27(2), 301-321.

Grunwell, S., Ha, I,. & Martin, B. (2008). A comparative analysis of attendee profiles at two urban festivals. Journal of Convention & Event Tourism, 9(1), 1-14.

Gursoy, D., Kim, K., & Uysal, M. (2004). Perceived impacts of festivals and special events by organizers: an extension and validation. Tourism Management, 25, 171-181.

Iso-Ahola, E. (1982). Towards a social psychology theory of tourism motivation: A rejoinder. Annals of Tourism Research, 9(2), 256-262.

Iso-Ahola, S. E. (1989). Motivation for leisure. In E. L. Jackson & T. L. Burton (eds.), Understanding leisure and recreation: Mapping the past charting the future (pp. 247-279). State College, PA: R.A. Venture.

Kim, Y. H., Goh, B. K., & Yuan, J. (2010). Development of a multi-dimensional scale for measuring food tourists’ motivations. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, 11(1), 56-71.

Lee, C. K. (2000). A comparative study of Caucasian and Asian visitors to a cultural expo in an Asian setting. Tourism Management, 25, 61-70.

Lee, C. K., Lee, Y., & Wicks, B. E. (2004). Segmentation of festival motivation by nationality and satisfaction. Tourism Management, 25, 61-70.

Maslow, A. (1954). Motivation and personality. New York: Harper and Row.

Mohr, K., Backman, K. F., Gahan, L. W., & Backman, S. J. (1993). An investigation of festival motivations and event satisfaction by visitor type. Festival Management and Event Tourism, 1, 89-97.

Nicholson, R. E., & Pearce, D. G. (2001). Why do people attend events: A comparative analysis of visitor motivations at four south island events. Journal of Travel Research, 39(4), 449-460.

Park, K., Reisinger, Y., & Kang, H. (2008). Visitors’ motivation for attending the South Beach Wine and Food Festival, Miami Beach, Florida. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 25, 161-181.

Petrick, J. (2004). First timers’ and repeaters’ perceived value. Journal of Travel and Research, 43(1), 29-38.

Schneider, I. E., & Backman, S. J. (1996). Cross-cultural equivalence of festival motivations: A study in Jordan. Festival Management and Event Management, 14, 139-144.

Scott, D. (1996). A comparison of visitors’ motivations to attend three urban festivals. Festival Management and Event Tourism, 3, 121-128.

The Historical/Cultural Traveler. (2003). Washington, DC: Travel Industry Association.

Thomas, B. (2010, September 12). The sound & the fury – down home with Ole Miss, beauty queens, & literary greatness in Oxford, MS. Washington Post. Retrieved from http:// www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/09/03/AR2010090304967.html

Uysal, M., Gahan, L., & Martin, B. (1993). An examination of event motivation: A case study. Festival Management and Event Tourism, 1(1), 5-10.

Woosnam, K. M., McElroy, K. E., & Winkle, C. M. V. (2009). The role of personal values in determining tourist motivations: An application to the Winnipeg Fringe Theatre Festival, a cultural special event. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 18, 500-511.

Xie, H., Costa, C. A., & Morais, D. B. (2008). Gender differences in rural tourists’ motivation and activity participation. Journal of Hospitality & Leisure Marketing, 16, 368-384.

Yoon, Y., & Uysal, M. (2005). An examination of the effects of motivation and satisfaction on destination loyalty: A structural model. Tourism Management, 26(1), 45-56.

Yuan, J., Cai, L. A., Morrison, A. M., & Linton, S. (2005). An analysis of wine festival attendees’ motivations: A synergy of wine, travel and special events. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 1(1), 41-58.

APPENDIX A

Oxford Film Festival Survey

|