A Safe Place to Start Over:

The Role of Design in Domestic Violence Shelters

Sarah M. Kesler

Kansas State University

Keywords: design, shelter, domestic violence, environment, housing

Abstract

This literary analysis explores the design of crisis centers and shelter housing, specifically focusing on those organizations serving victims of domestic violence. It investigates the housing needs of people who are connected to the shelter and its function, such as victims of domestic violence, their children, the administrative workers, and also the abuser. It examines the shelter itself by identifying the various types of space used by victims living in the shelter and how each space affects users of the facility. It also considers which aspects of shelter design influence users most, such as privacy and security, the ability to control their environment, and the effects of the transition from a familiar place to a new location. Information on the design of shelters and the services provided is not readily available (Pable, 2010; Correia & Melbin, 2005). Research specifically about centers that serve victims of domestic violence and their children is even more difficult to come by. To gain a wider perspective and better understanding of the subject, research on homeless shelters and transitional housing was included in the review. In order to more accurately see the role of a crisis center in victims’ lives, staff members from a local crisis center were interviewed to gain insight into the procedures of the shelter environment. It was discovered that design has an enormous impact on both victims residing in the shelter and administrative staff who work there. The design, space planning and functionality of the shelter affect victims psychologically, as well as physically and emotionally impacting them (Baker, Cook, & Norris, 2003). By using the conclusions found through research to improve shelter environments, victims have a better chance of recovering from their crisis situation and becoming successful members of society.

Introduction

Space would have little value if it were not intended for the people that use and inhabit that space. Environments created specifically for human habitation require careful consideration in their design in order to fulfill the intended occupant’s needs (Kopec, 2006). Some environments call for more specialized design elements than others. Domestic violence shelters are spaces with some of the most particular design requirements of any built environment. Shelter housing is also one of the most overlooked types of space in the field of design. Although awareness and the number of programs serving victims of domestic violence is steadily increasing, information about existing programs and the characteristics that prove them to be successful is scarce (Correia & Melbin, 2005). This paper, along with the corresponding research, aims to contribute to the body of knowledge and make progress toward filling in gaps in the area of design for shelter housing and crisis center programs.

Developing a Program

When developing a new program for shelter housing, or reinventing an existing program, it is important to consider the needs of both the victims and the staff who interact with the shelter environment. In terms of the needs of victims living in a shelter environment, understanding the frame of mind these people are in when entering the setting can go a long way to understanding how to best meet their needs through design. Security, privacy, and a sense of home become much more important to these people because of their previous experiences. Designers should focus on elements that strengthen these concepts in order to accommodate victims’ needs while staying in shelters Aspects of design for the administrative component of shelter housing and crisis centers must allow staff to provide the maximum amount of resources to victims, thereby improving the victim’s chance of succeeding. By including research into the design of a space the design becomes better informed and more specifically meets the needs of that particular space. When design fulfills the needs of the user, the environment becomes supportive.

More recently, programs have adopted the Continuum of Care Model (Pable, 2010). Figure 1 demonstrates that this model is made up of three types of housing intended to support victims in the different stages of a crisis situation. The first stage focuses on emergency shelter, providing an escape from the abusive situation. This stage typically lasts up to 90 days. Second, the transitional housing stage is illustrated. Transitional housing environments accommodate residents anywhere from three months to a year. The focus of this period is regrouping, assessing the situation, and planning for long-term goals. Long-term housing is the final type of housing in this model. It is meant to be the final stage of housing and the most permanent. Throughout each of these stages it is important to continue offering resources and advocacy to victims of domestic violence, because studies have shown that continued contact with an advocate offers a greater chance of making connections within the community and breaking the cycle of abuse (Lyon, et al., 2008).

Figure 1: Continuum of Care Model, based on Pable, 2010

Review of Relevant Literature

Although information pertaining specifically to domestic violence programs is limited, research regarding similar programs and organizations can be used to inform the design of new programs. Homeless shelter programs share many similarities to domestic violence programs. The fastest growing homeless population consists of families, mainly single women with children (Pable, 2010; US Conference of Mayors, 2009). Domestic violence is a major contributing factor in the homelessness of women and children and half of all homeless women and children have left home because of domestic abuse (Pable, 2006). Understanding the cycle of domestic violence and homelessness programs is the key to developing effective domestic violence shelters and crisis centers.

The Cycle of Domestic Violence

Domestic violence and intimate partner abuse is behavior used by one person in a relationship to exert control over the other (Creative Communications Group, 2009). Victims of domestic violence are one of the most diverse groups of people. Age, race, socioeconomic status, level of education, marital status, sexual orientation, location, and many other factors have no proven effect on the likelihood of becoming a victim of domestic violence (Lyon, Lane, & Menard, 2008). The most predominant factor of victimization is gender (National Law Center on Homelessness and Poverty, 2007). Nearly 95 percent of all domestic violence cases report women as the victim (Payne & Wermeling, 2009). Men can be victims of domestic violence as well; however, they typically seek out alternatives to emergency shelter provided by domestic violence programs (Lyon, Lane, & Menard, 2008). Domestic violence is a repetitive process, and once it begins it becomes very hard to escape the situation.

Domestic violence is a cycle of actions and reactions as demonstrated in Figure 2. The honeymoon period is an episode of calm or even excessive kindness shown by the abuser to the victim. It does not last though and tension begins to build slowly. This tension leads to a breaking point. This point is where abusive incidents occur. After abusive incidents, whether because of remorse or an attempt to regain trust, the relationship reenters the honeymoon stage, thereby completing the cycle. Victims are most likely to leave an abusive relationship after an incident of violence occurs, which offers an explanation for the recurrence of the honeymoon period. Studies show that victims are at the highest risk for injury or death from a partner at the point of separation and that many women choose to stay in an abusive relationship in the hopes of avoiding retaliation against themselves or their children (Payne & Wermeling, 2009). Research also shows that if a victim does choose to leave an abusive situation it takes multiple attempts, and therefore causes multiple periods of homelessness, before the victim actually escapes the cycle of violence (National Coalition Against Domestic Violence, 2011). The most common reason charges are not brought against an abuser is fear of retaliation coupled with the victim’s belief that law enforcement will not be supportive (Payne & Wermeling, 2009). Protection orders and temporary restraining orders can be put in place to protect victims but these are not valid long-term solutions to the overall problem. Victims tend to gather all of the information they can about the options available to them before taking the step to leave an abuser (Lyon, et al., 2008). Researchers have examined the Survivor Theory (Collins, 2010). Survivor Theory states that women who have been continuously abused seek out ways to survive their conditions by persisting through adversity and adapting to their situation (Collins, 2010).

Figure 2: Cycle of Violence, based on Payne & Wermeling, 2009

For victims of domestic violence trying to escape and obtain safety, autonomy, and independence, access to affordable housing is critical (Pennsylvania Coalition Against Domestic Violence, 2004). Housing becomes an immediate need after a victim leaves the abuser; first short-term, then long-term solutions must be arranged (Baker, Cook, & Norris, 2003). The legislative process of separating from the abuser and searching for affordable housing options and resources is lengthy, but housing and safety needs of victims are immediate problems (PCADV, 2004). If affordable long-term housing cannot be found within a reasonable amount of time, victims are much more likely to return to the environment of their batterer. When forced to return to an abusive situation the level of violence escalates as a result of the abuser trying to regain control (PCADV, 2004). Many times the abuser attempts to control economic resources, further limiting the victim (Correia & Rubin, 2001). This means that shelter programs and crisis centers become crucial housing resources for victims leaving an abusive situation.

Shelter Housing

Homelessness causes stress for victims, as well as being a result of the stress they are experiencing in their lives due to domestic violence (Banyard & Graham-Bermann, 1998). Shelters are intended to be used as transitional housing; they serve as a resource, not permanent living arrangements (Correia & Melbin, 2005). By meeting short-term needs of safety, homeless shelters give victims of domestic violence valuable time to seek out more appropriate housing accommodations and plan for their future (Correia & Melbin, 2005). Victims frequently resort to seeking refuge from domestic abuse in homeless shelters, instead of organizations specifically for victims of domestic violence (PCADV, 2004). Although these facilities offer a place to stay, they often can’t accommodate the victim’s emotional and psychological needs and they rarely meet the security needs of a victim suffering from domestic violence (PCADV, 2004).

Lyon, Lane, and Menard (2008) emphasized this idea by explaining that domestic violence shelters address needs that cannot be met elsewhere. Shelter programs and crisis centers provide a wide range of resources and assistance to victims and survivors of domestic violence. Services needed immediately by victims upon entrance to shelter are safety from their abuser, information about housing options, emotional support, and resources for children (Lyon, et al., 2008). Other basic resources provided to shelter inhabitants and outside clients include individual and group counseling, legal advocacy, child services, healthcare treatment, safety planning, skill development, and goal-setting (Bennett, Riger, Schewe, Howard, & Wasco, 2004; Correia & Melbin, 2005).

Domestic violence shelters are reported to be one of the most helpful resources, but one of the least used; law enforcement is one of the most used but least helpful resources (Baker, et al., 2003). Victims nearly always seek help but are reluctant to seek help again if they feel they are treated badly (Baker, et al., 2003). In locations that do not offer shelters specifically for victims of domestic violence, collaboration with other organizations in the community allows for a wider range of services that can be provided to victims (Correia & Melbin, 2005). However, when resources are allocated to victims of homelessness, domestic violence, and other crises, greater stress is placed on the programs that serve such a large client base (Correia & Melbin, 2005).

Transitional Housing

Transitional housing, also called second-stage housing, includes many kinds of support services and resources that are available to victims of domestic violence. Second-stage housing is typically offered after time spent living in shelter housing and serves as a bridge between temporary and permanent housing accommodations (Correia & Melbin, 2005). Victims of domestic violence are often denied housing opportunities, and even evicted from their current living arrangements because of their connection to crimes involving domestic violence (Weiser & Boehm, 2002; NLCHP, 2007). Legal policies hold victims accountable for criminal acts committed by family members, including abusive partners (Baker, et al., 2003). Because of this prejudice, programs that offer both shelter housing and assistance finding housing after leaving shelter are the most helpful to victims. Victims who were able to find and maintain long-term affordable housing solutions were less likely to return to their abuser or emergency housing situations (National Center on Domestic and Sexual Violence, 2004). Increased access to support programs is also important for victims to become more independent and successful (Sullivan, 2011).

Many shelters limit the length of a victim’s stay in the shelter, typically between 30 and 90 days, but this brief period of time is not long enough for a woman, and potentially her children, to begin a new life (Baker, et al., 2003). It is imperative that a program work with victims to accomplish goals and recognize that each situation is unique and must be treated as such (Correia & Melbin, 2005). Each individual’s situation presents a different timeline for accomplishing independence; programs that are flexible are the ones that are most useful and effective. Transitional housing gives victims an opportunity to regroup, assess current circumstances, begin making long-term goals, and develop strategies to become independent (Bennett, et al., 2004; Pable, 2010).

Method

The context of this research study was to utilize shelter housing and crisis center resources to further inform the design needs of similar facilities. The study took place in a Kansas organization that provides resources and shelter housing to victims of domestic violence and sexual assault. The Crisis Center, Inc. serves Clay, Geary, Marshall, Pottawatomie, and Riley counties in Kansas. Their services include statewide and local hotlines, safe shelter, advocacy, referrals, children’s services, support groups, counseling, and assistance with legal proceedings (The Crisis Center Inc., 2011). Collecting information from an existing shelter was ideal because it is able to demonstrate positive and negative aspects of design based on real experiences.

In order to gather the most accurate information from the most direct sources, several members of the administrative staff were interviewed personally. Based on the review of available literature on shelter housing and services for victims of domestic violence a series of questions was developed to investigate specific design needs of crisis centers. This series of questions was posed to three key administrative staff members in order to gain insight into the shelter experience based on their knowledge and work with clients who have utilized shelter services. In an attempt to preserve the safety of the organization and their clients the staff member’s names and official job titles will be kept anonymous, following IRB protocol. Following security protocol, clients of the shelter were not interviewed in order to maintain their safety and wellbeing.Each staff member chosen to answer the set of questions performs a different role in the overall structure of the organization. They work directly with clients in the shelter setting and in the administration office. These individuals were chosen because of the diversity of their roles within the organization and the wide range of perspectives they could offer this study. The staff members’ experience with the organization ranges from 18 months to over 20 years, giving insight into the development of the shelter program over time.

In addition to the review of available literature about shelter programs and the interviews with key staff members, an inventory of existing spaces was conducted within the crisis center setting. This inventory provided a context for the answers given by informants during the interviews. It also provided a foundation of place types necessary for shelter environments and the interaction in these spaces. For a full inventory of spaces found within the shelter environment see Table 1.

Table 1: Inventory of space types

Room Type No. of Rooms

Public or Private

Front Porch

1

Public

Foyer

1

Public

Living Room

1

Public

Dining Room

1

Public

Kitchen

1

Public

Play room

1

Public

Vertical circulation (stairs)

2

Public & Private

Food storage

1

Private

Laundry

1

Private

Donation Storage

1

Private

Single Women’s Bedroom

2

Private

Women & Children’s Bedroom

4

Private

Bathroom

4

Public & Private

Social area

2

Public

Meeting room

1

Private

Administrative Offices

3

Private

Staff Entrance

1

Private

Results

The information gained during the interviews provided valuable first-hand information about the shelter program. Recurring themes included a sense of home, comfortable spaces, privacy, and security. It was determined from the interviews that these concepts are the foundation that make shelter housing and crisis centers successful to the clientele they serve. Although these concepts make up the foundation, many other aspects of design also contribute to the supportive nature of shelter housing and were discussed during the interviews.

Sense of Home

All three staff members interviewed advocated the importance of the shelter feeling like home for the women living there. These women have left nearly everything behind in an attempt to escape an abusive situation; they would not be living in shelter if other options were available to them. Human beings develop feelings of place attachment to spaces that they have inhabited for years or where there is a particularly strong emotional bond (Kopec, 2006). Suffering from domestic violence is an example of an emotional bond, even though it is a negative experience for the victim. Kopec (2006) explained that there are often negative outcomes when place attachment is lost, especially when the bond is forcibly severed as in the case of a domestic violence victim fleeing the home.

After the victim leaves an abusive situation it becomes vital to give them the opportunity to develop a sense of place within the shelter environment. When a level of comfort and feelings of safety are associated with a space, a sense of place develops for that individual (Kopec, 2006). Staff members explained that relocating to a shelter environment that promotes these ideals gives victims a feeling of belonging and security, which encourages healing and independence. This is further proof of the notion that housing is much more than just protection from the elements; inhabitants must find a sense of dignity and pride in their home in order to truly connect with the space (Davis, 1995).

Comfortable Space

Many factors contribute to the level of comfort in a space and these vary with each individual that uses the space. Although shelter rooms meet code requirements they still often seem crowded to those inhabiting the space, as seen in Figure 3 (Pable, 2010). Crowding is the feeling of too many people and too little space, and it varies depending on cultural norms and personal preference. In order to avoid crowding it is important to consider density in each area of the shelter. Spaces that are highly traffic areas, such as kitchen and living spaces, should be larger to accommodate the flow of traffic. Areas such as bedroom and office spaces that do not have such a high traffic demand can be smaller and denser.

Figure 3: Bedroom space from a shelter case study, Pable, 2010

Figure 4: Personal items displayed on a countertop

Privacy and Security

Privacy is the ability to control access for ourselves and our environment (Kopec, 2006). This becomes important to victims of domestic violence because their lives are often defined by lack of control (Pable, 2010). The level of privacy desired varies based on social situations in which individuals find themselves (Kopec, 2006). Staff members repeatedly addressed the issue of privacy (Anonymous, personal communication, November 4, 2011). Shelter housing is utilized by a variety of people, such as staff members, interns, clients, children, and volunteers. Having a sense of privacy among the assortment of users makes it much easier for clients to develop a sense of belonging in the shelter and personalize their space (Pable, 2007). In public spaces privacy is not as essential to the comfort of users; however, in areas like bedrooms it is very important. Offering multiple setups for inhabitants is an excellent way to give them the opportunity to make the space their own. For example, several bedrooms that are designed to house women and their children and separate rooms that are intended for single women with no children ensure privacy from strangers.

It is important to have spaces that are public as well as ones that are private (Pable, 2007). Staff members observed public spaces, such as the kitchen and the patio area used for smoking, as places where people interact and relationships are developed. One staff member indicated that building relationships with other victims helps women feel more supported by their environment (Anonymous, personal communication, November 4, 2011). It is also vital for shelters to have areas of privacy for activities like counseling, legal advocacy, and making phone calls. Having spaces with varying degrees of privacy in the shelter offers a wider range of activities that can be conducted inside the shelter, making it more secure and convenient for the clients.

Shelter housing should also be secure, especially shelters that take in victims of domestic violence. Victims use shelter housing to escape abusive and often dangerous situations. In order to protect clients it is vital for shelters to take precautions to ensure the safety of the people staying in shelter housing. During interviews staff members pointed out features that served security purposes, such as privacy fences so that inhabitants could still enjoy being outside, locks that require an entry code so that access can be restricted and reset in case of a security breach, and a lack of distinguishing features on the façade of the shelter to help it blend in with the surrounding area and remain as inconspicuous as possible (Anonymous, personal communication, November 19, 2011).

Other Important Features

Material use is easy to overlook when designing spaces to solve larger problems. It is important to realize that sustainability and durability of materials, although a seemingly small aspect, is also important to the overall design of a shelter environment. Many crisis center organizations are funded by a combination of federal grants and private donations (Correia & Melbin, 2005; Anonymous, personal communication, November 2, 2011). Materials and furnishings that are durable and sustainable will be more beneficial because they will last longer and stand up to the wear and tear of so many users that circulate through the facility.

Although the main objective of shelter housing and crisis centers is to empower and assist victims, it is important to remember that these organizations must have an administrative facet as well. The business functions of the organization are important to successful management so that centers can continue to benefit victims. Although administrative spaces are necessary to the function of the organization, the location should be separate from the actual shelter. Administrative staff members are not part of the everyday function within the shelter, although a location with close proximity to the shelter is helpful when the responsibilities do overlap (Anonymous, personal communication, November 2, 2011). Administrative offices are also important for serving clients who do not choose to live in shelter housing but still request services from the organization.

The location of the shelter is also something that must be considered. Although privacy and anonymity is desired due to the nature of the clients’ situations, shelters are committed to assisting victim’s begin new lives after leaving an abusive situation. The shelter should be located in close proximity to shopping, employment, and education. Living nearby offers more opportunity for victim’s to be independent and self-sufficient by being in control of those aspects of their life (Anonymous, personal communication, November 19, 2011).

Storage within the shelter space and administrative offices is necessary as well. Because domestic violence shelters must fit in with the surrounding community and neighborhood, construction of new structures is not always possible or reasonable. Using existing structures has the benefit of blending in with the surrounding area, but the drawback is not being able to specify everything to exactly meet the needs of the organization. Utilizing space so that the maximum benefit is gained becomes essential. Typically, victims living in shelter housing do not bring many things with them. Storage for these items in shelter is important, though; having a space to put personal items gives inhabitants the chance to make the space their own and personalize it (Pable, 2010). Figure 4 shows a counter space that is used to store and display personal items. Storage is also important for donated items that are available to women in shelter. Administrative offices require storage space that is private to keep confidential files and records of clients.

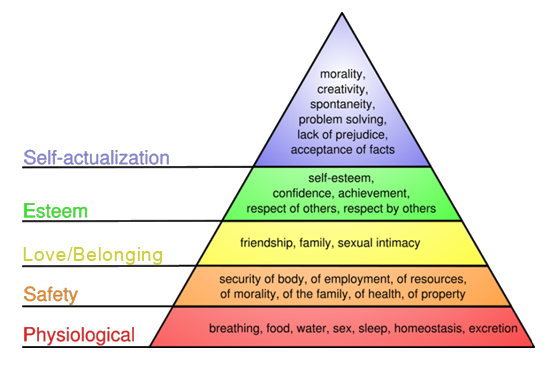

Application of Research

Architecture and design are typically not the first elements considered when deciding how to provide for the homeless or victims of domestic violence who have become homeless (Davis, 2004). Most often provision for the homeless is about supplying them with the basic resources to survive. Based on Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, humans prioritize their own needs (Kopec, 2006). Figure 5 shows a diagram of Maslow’s theory. At the bottom of the pyramid diagram are physiological needs. The next tier of the diagram is safety, followed by belonging, self-esteem, and finally, self-actualization. This can be used as a guide in designing any space for humans to inhabit. By creating an environment that allows people to achieve each level on the Hierarchy of Needs, the space becomes supportive of those individuals, no matter what situation they find themselves in.

Figure 5: Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs.

At the physiological level, shelters should provide basic needs of victims: food, water, a roof over their head, and clothing to wear. The research shows that victims of domestic violence are in immediate need of safe housing options while they search out other options and plan for the future (Pable, 2010). By providing shelter to victims of domestic violence, organizations increase individuals’ chance of survival and give them an opportunity to improve their lives. Shelter housing must have enough space to accommodate activities for all those staying in the shelter. In the shelter studied for this research project the kitchen had become a center of activity for the entire facility (Anonymous, personal communication, November 19, 2011). Storage must also be considered so that food is adequately kept until use and clothing and other provisions can be kept nearby for use by those staying in the shelter, like the donations shown in Figure 6. The physiological level is the most straightforward set of needs.

Figure 6: Donation storage space in a shelter

The next level on Maslow’s diagram is safety needs. This becomes slightly more difficult to accomplish than physiological needs, and needs on this level cannot be met until the first level has been satisfied. This level includes personal safety, protection of family, health, security, and employment. By providing a shelter environment that is secure to victims and their children, a sense of security is developed. This allows inhabitants to focus on other aspects of their lives, like planning for the future. Resources provided by shelter organizations also aim to help victims create plans to ensure safety, find long-term housing solutions and employment to support themselves and their families (Anonymous, personal communication, November 4, 2011). By making these resources available to victims the organization provides means to fulfill this level of needs.

After attaining success in the first two levels of the Hierarchy of Needs, physiological and safety, the focus turns to belonging. This level includes a sense of connection with family and friends and development of supportive relationships. Shelter organizations promote relationships with other women in shelter housing as well as with advocates from the organization. Studies have shown that women who have an advocate assisting them were able to more effectively find and access resources that gave them a better quality of life (Briere & Jordan, 2004). Several spaces in the shelter studied in this project became gathering places based on their function, the kitchen at mealtimes and the patio used for smoking (Anonymous, personal communication, November 19, 2011). Relationships between inhabitants provide a support system and a sense of belonging at the shelter for the women and their children; staff members confirmed that these relationships continue even after the women left the shelter environment (Anonymous, personal communication, November 2, 2011).

The last two levels of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs are self-esteem and self-actualization. Self-esteem includes confidence, a sense of achievement, and respect of others. Shelter housing may provide the means for inhabitants to rise to this level but self-esteem comes once victims transition out of the shelter and into a more permanent housing solution that they have worked to attain with the help of resources offered by the shelter. Self-actualization is the level that allows individuals to exercise creativity and spontaneity, develop their sense of morality, experience purpose for their life, and achieve their potential as a survivor. This is ultimately the goal of shelter programs and crisis centers; empowering women and children to live safer lives, make informed decisions, and grow personally is the philosophy that drives organizations that serve the victims of domestic violence (Correia & Melbin, 2005). These levels may not be achieved in shelter, but without the support of the shelter environment victims would not be able to reach lower levels on the Hierarchy of Needs and would therefore lose the chance to attain the higher levels and reach self-actualization.

Summary

Areas of Future Research

Based on the existing research there are gaps in the body of knowledge regarding the design of shelters specific to victims of domestic violence. Design of shelter housing and crisis center organizations could be improved when more research is conducted and the findings are applied to the environments. Future studies should continue to focus on the needs of victims using these spaces; the inhabitants of shelters are the ones who are intended to benefit from their design and services.

Studies conducted in the future would benefit most from observing the user of the space and interactions with the shelter environment. A few studies have been conducted that alter rooms in a shelter facility and compare user satisfaction between the two environments (Pable, 2010). By discovering exactly what domestic violence victims require of a shelter, it becomes much easier to design an environment that fully supports them. Using what is already known about design environments gives researchers a good starting point to continue exploring shelter housing and crisis center design.

After researching shelter housing and crisis centers, and related design elements, some of the gaps that previously existed in the body of knowledge have been filled in; although, there will always be more that can be discovered and applied. Using this research to design a new shelter facility, or to renovate an existing organization, and then observing the effects of the changes to design elements would validate the research and hypotheses from this project.

When faced with a situation that forces victims to leave their home, it becomes vital that they find a new place to call home, even if it is temporary. Design professionals have an advantage here because they understand elements that make environments more supportive to the user. Using research and knowledge to inform the design of shelter housing and crisis centers is an opportunity to create environments that offer hope, encouragement, and optimism to victims. The challenge now is investigating the best way to construct environments that present victims with a sense of home, self-identity, and a place in society.

The purpose behind all of the research and interviews and exploration of shelter housing and crisis centers was to improve the shelter experience and lives of those who use these spaces. Architecture and design contribute to communities both by fulfilling specific requests and by using knowledge and expertise to meet needs that are not already addressed (Bell, 2004). If concepts that improve design can be implemented in shelter housing and crisis centers, it can be inferred that the programs will be improved because of these elements. It is important to look past the obvious in this area of design, because there is no specific program for the design of a supportive shelter environment; designers must gather information related to the program in combination with design theories about space and users in order to produce the most supportive environment possible.

References

Baker, C. K., Cook, S. L., & Norris, F. H. (2003). Domestic violence and housing problems. Violence Against Women, 9(7), 754-783. doi: 10.1177/1077801203253402

Banyard, V. L., & Graham-Bermann, S. A. (1998). Surviving Poverty: Stress and coping in the lives of housed and homeless mothers. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 68(3), 479-489.

Bell, B. (2004). Good deeds, good design: Community service through architecture. New York, NY: Princeton Architectural Press.

Bennett, L., Riger, S., Schewe, P., Howard, A., & Wasco, S. (2004). Effectiveness of hotline, advocacy, counseling, and shelter services for victims of domestic violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 19(7), 815-829. doi: 10.1177/0886260504265687

Briere, J., & Jordan, C. E. (2004). Violence against women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 19(11), 1252-1276. doi: 10.1177/0886260504269682

Collins, J. D. (2010). Understanding help-seeking behavior of abused women: A quantitative analysis of domestic violence shelter archives (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Capella University, Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Correia, A., & Melbin, A. (2005). Transitional housing services for victims of domestic violence. National Online Resource Center on Violence Against Women. Retrieved from http://new.vawnet.org/Assoc_Files_VAWnet/TransHousingServices.pdf

Correia, A., & Rubin, J. (2001). Housing and battered women. VAWnet- Applied Research Paper Series. Retrieved from http://www.ncdsv.org/images/Housing_Battered_Women.pdf

Creative Communications Group. (2009). Definition of domestic violence. Retrieved from http://www.domesticviolence.org/

Davis, S. (1995). The architecture of affordable housing. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Davis, S. (2004). Designing for the homeless. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Kopec, D. A. (2006). Environmental psychology for design. New York, NY: Fairchild Publications, Inc.

Lyon, E., Lane, S., & Menard, A. (2008). Meeting survivors’ needs: A multi-state study of domestic violence shelter experiences. Retrieved from https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/225025.pdf

National Center on Domestic and Sexual Violence. (2004). Housing, homelessness, and domestic violence. National Network to End Domestic Violence. Retrieved from http://www.ncdsv.org/images/housingdvfactsheet1.pdf

National Coalition Against Domestic Violence. (2011). Domestic violence and housing. Retrieved from http://www.ncadv.org/

National Law Center on Homelessness and Poverty. (2007). Lost housing, lost safety: Survivors of domestic violence experience housing denials and evictions across the country. Lawyers Working to End Homelessness. Retrieved from http://www.nlchp.org/content/pubs/NNEDV-NLCHP_Joint_Stories%20_February_20072.pdf

Pable, J. (2006). Design response to homelessness. Implications, 4(7). Retrieved from http://www.informedesign.org/_news/jul_v04r-p.pdf

Pable, J. (2007). Homeless shelter design: a psychologically recuperative approach. Journal of Interior Design, 32(3), 91-99.

Pable, J. (2010). The transitional homeless shelter family experience. Unpublished manuscript, Department of Interior Design, Florida State University, Tallahassee, Florida.

Payne, D., & Wermeling, L. (2009). Domestic violence and the female victim: The real reason women stay. Journal of Multicultural, Gender, and Minority Studies 3(1). Retrieved from http://www.scientificjournals.org/journals2009/articles/1420.pdf

Pennsylvania Coalition Against Domestic Violence. (2004). Housing resources for domestic violence survivors and their advocates. Retrieved from http://www.pcadv.org/Resources/Housing.pdf

Sullivan, C. M. (2011). The impact of domestic abuse victim services on survivors’ safety and wellbeing. Unpublished manuscript. Department of Psychology, Michigan State University, Lansing, Michigan.

The Crisis Center Inc. (2011) Our services. Retrieved from http://www.thecrisiscenterinc.org/services.htm

U.S. Conference of Mayors. (2009). 2008 Status Report on Hunger & Homelessness. Retrieved from http://usmayors.org/pressreleases/documents/hungerhomelessnessreport_121208.pdf

Weiser, W. R., & Boehm, G. (2002). Housing discrimination against victims of domestic violence. Journal of Poverty Law and Policy. Retrieved from http://www.legalmomentum.org/assets/pdfs/housingdiscriminationclearinghouse.pdf

Images

Figure 1: Kesler, S.M. (2011). Continuum of care [diagram].Figure 2: Mid-Shore Council on Family Violence. (2011). Cycle of violence [diagram].

Figure 3: Pable, J. (2010). Shelter bedroom [photograph].

Figure 4: Pable, J. (2010). Personalization of space [photograph]

Figure 5: Finkelstein, J. (2011). Maslow’s hierarchy of needs [diagram].

Figure 6: 89.3 KPCC. (2009). Donation storage [photograph]. Retrieved November 26, 2011 from http://www.scpr.org/news/2009/07/15/1787/domestic-budget/

Annotated Bibliography

Books

Abrahams, H. (2007). Supporting women after domestic violence: loss, trauma and recovery. Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

This book was not available in the library while working on this research project. After investigating the topic more I found that this source was not specific enough to the topic of my paper to further pursue the reference.

Bell, B. (2004). Good deeds, good design: Community service through architecture. New York: Princeton Architectural Press.

This book emphasized the importance of design as a service to the community. It depicted design as something that was not simply for high-end spaces and the wealthy. Bell explained how every space can benefit from good design and that as professionals in the field we have a responsibility to apply our knowledge of design to every project, no matter how small.

Although the majority of the information in this book was directed toward homeless shelters and serving the homeless population it contained very relevant information that can be applied to shelter housing of any kind, including domestic violence. The most informative sections to this topic were about developing the community and relating to the social needs of the clients.

Cooper, J., & Vetere, A. (2005). Domestic violence and family safety: a systematic approach to working with violence in families. London: Whurr Publishers.

This source had good information about domestic violence as a whole but after reading deeper there appeared to be other sources that held the same information and presented it more clearly and more concisely. It focused more on serving the victims and families by counseling and in a psychological approach. There was no information about design of shelter housing or needs of victims while in shelter environments. If I were to continue researching this topic I would include this source in order to give the information more background.

Davis, S. (1995). The architecture of affordable housing. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Although this book had a lot of very useful information, not much of it related to the topic of domestic violence shelters and crisis centers. There were design concepts about affordable housing that helped inform the architectural program developed from research. The information focused on affordable housing to provide for low-income residents and making affordable housing equal to other types of housing by applying good design. It gave very practical information such as cost and accessibility.

Davis, S. (2004). Designing for the homeless. Berkeley: University of California Press.

This book was also directed mainly toward homeless shelters, although it did mention domestic violence a few times. The concepts covered in this book, such as developing an architectural program for shelter housing and showing that design can solve many of the problems of the homeless population were useful in researching for this topic. It also addressed the issue that design is not just for the wealthy or grandiose spaces; everyone deserves to live in well-designed spaces. It covered the cost of homelessness, both from a victim’s perspective and a design perspective. There were also several case studies and examples throughout the text to demonstrate instances that related to the topic.

Kopec, D.A. (2006). Environmental psychology for design. New York: Fairchild Publications, Inc.

This textbook gave helpful information on housing needs and psychological theories that contribute to housing situations. It helped to make connections between information about domestic violence and housing needs of victims. It also closed gaps between information gathered from interviewed staff members and design concepts. The sections on the meaning of home and human needs for space were the most useful in making these connections

Journal Articles

Baker, C.K., Cook, S.L., & Norris, F.H. (2003). Domestic violence and housing problems. Violence Against Women, 9(7), 754-783. doi: 10.1177/1077801203253402

This was a study conducted to observe the results of different types of support systems available to victims of domestic violence. Specifically the researchers looked at informal support networks, such as family and friends, and formal systems, like welfare, shelters, police, and courts. It explored the relation between experiencing domestic violence and experiencing homelessness. The researchers recognized that there was not much information currently available about the link between homelessness and domestic violence. They studied women who were using the resources mentioned above in order to gain insight into the demographic of the users and the success of the systems.

This study was very helpful for my research project because it illustrated the different types of support systems used by victims and the success of those systems. The section that showed the effectiveness of shelter housing was especially relevant to my project. Throughout the study there was information that was not expressly related to shelter housing but still provided information about users and their needs.Banyard, V.L., & Graham-Bermann, S.A. (1998). Surviving Poverty: Stress and coping in the lives of housed and homeless mothers. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 68(3), 479-489.

This study focused more specifically on homelessness in general with some information connected to domestic violence. The main idea of this article was a focus on stress because of homelessness, especially in women who were supporting children. It explored the effect of being in a family that was homeless as opposed to being single and homeless. The psychological effects on the subjects were less severe when a family unit was available for support. The researchers also found that women who were supporting children experienced a different kind of stress than those who were single. Mothers were more concerned for the wellbeing of their children and made more sacrifices to provide for them than required by single women.

Although the subject of this study was not directly related to the topic of my research it still provided valuable information about the psychological aspect of homelessness, especially because it was focusing on women and children. The information about stress and the cause informed ways to reduce stress through design of shelters and other resources used by this population.Bennett, L., Riger, S., Schewe, P., Howard, A., & Wasco, S. (2004). Effectiveness of hotline, advocacy, counseling, and shelter services for victims of domestic violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 19(7), 815-829. doi: 10.1177/0886260504265687

The focus of this research study was the services provided to victims of domestic violence and their effectiveness for those people. Although the information on advocacy, counseling, and hotline services helped give a better idea of what victims had available to them and how those resources helped victims cope, it was the section about shelter services that was the most helpful in informing what design aspects are most useful for victims of domestic violence.

This study only reported on services in Illinois. It would have been more helpful to have a wider range of services, but it was helpful that the location was in the Midwest. The study was also conducted for only one year. If the study had been over a longer period of time I think that the data would have been more varied and given a better idea of long-term information.Briere, J., & Jordan, C.E. (2004). Violence against women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 19(11), 1252-1276. doi: 10.1177/0886260504269682

Briere & Jordan’s study focused a lot on the mental health aspect of victimization from domestic violence. They explored the direct effects on women and also the variables that were specific to individuals based on their situation or their background. They were very specific that domestic violence is a situation that affects each person differently. The best way to serve this demographic is to provide options that are flexible so that they can be adjusted to fit each individual.

This was helpful in developing a program for shelter housing because it stressed the importance of flexibility and personalization of programs for individual people. It really showed that one solution will not work for every person but variations on that solution change it so that the majority of the population benefits.Pable, J. (2007). Homeless shelter design: a psychologically recuperative approach. Journal of Interior Design, 32(3), 91-99.

This article was about Dr. Pable’s work on homeless shelter design. The goal of the design was to make the shelter psychologically supportive for the users of the space. It used design concepts in a way that improved the shelter and the overall experience of both inhabitants and staff members.

This conceptual design was intended to be used for a homeless shelter but the theories and concepts can be applied to any type of shelter, including one that serves victims of domestic violence. Dr. Pable also used Maslow’s theories to inform the design of this center.Payne, D., & Wermeling, L. (2009). Domestic violence and the female victim: The real reason women stay. Journal of Multicultural, Gender, and Minority Studies 3(1).

This research covered the theoretical use of police intervention, victim advocacy, and community response to domestic violence. The research into resources was very helpful in discovering what resources were the most useful for assisting victims and the variations of those in order to serve a broader population. This study was not very large; had there been more information about the design of the shelter it may have helped more to inform my research project.Online Articles

Correia, A., & Melbin, A. (2005). Transitional housing services for victims of domestic violence. National Online Resource Center on Violence Against Women. Retrieved from http://new.vawnet.org/Assoc_Files_VAWnet/TransHousingServices.pdf

This study first looked at existing services to victims of domestic violence and the effectiveness of those services. The researchers used specific examples from locations across the United States in order to study programs and develop conclusions. Seeing examples from actual programs, what services were helpful, and which ones needed improving was important for designing a program that was the most supportive.Correia, A., & Rubin, J. (2001). Housing and battered women. VAWnet- Applied Research Paper Series. Retrieved from http://www.ncdsv.org/images/Housing_Battered_Women.pdf

This study focused on housing needs of battered women. It explored barriers that are faced by these women while trying to fulfill their housing needs and how those barriers impacted the women. Conclusions were found based on other research. This study informed my research about barriers that would need to be overcome in order to create a supportive environment for battered women. It was also a good source of resources that further developed the project.Lyon, E., Lane, S., & Menard, A. (2008). Meeting survivors’ needs: A multi-state study of domestic violence shelter experiences. National Resource Center on Domestic Violence. Retrieved from https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/225025.pdf

This was a study that looked at domestic violence shelters in eight different states in order to learn more about what kinds of services are provided by the shelter in terms of the needs of the victims who turned to the shelter. It was a 6-month long study that observed 215 shelters. States were chosen to give the widest range of demographics possible so that as many different situations as possible could be observed. The range of programs was helpful in giving an overall picture of the current state of domestic violence programs.Pable, J. (2006). Design response to homelessness. Implications, 4(7). Retrieved from http://www.informedesign.org/_news/jul_v04r-p.pdf

In this article for InformeDesign Dr. Pable explores homelessness in America and what designers can do to contribute to a solution. It was focused more toward homeless shelters, not domestic violence, but there were important findings that inform design of any shelter type. It explained the process of emergency shelter and finding more permanent housing solutions. It showed the Continuum of Care model, used in helping homeless people solve their housing problems. The study even touched on program considerations, which were very helpful for my research in developing a program for domestic violence shelters.National Center on Domestic and Sexual Violence. (2004). Housing, homelessness, and domestic violence. National Network to End Domestic Violence. Retrieved from http://www.ncdsv.org/images/housingdvfactsheet1.pdf

This is a fact sheet put together based on research done nationally by the Center on Domestic and Sexual Violence. It focused on the link between homelessness and domestic violence and the difficulties that victims face in trying to obtain housing solutions for themselves and their families. It also showed that victims have trouble getting housing because of their relation to violence situations and the barriers with which they are faced. By helping victims with housing they have a better chance of success in other areas of their lives also. This was helpful in determining the major housing problems related to domestic violence. From there it was apparent that resources to find housing were a top priority for shelters to help victims.National Law Center on Homelessness and Poverty. (2007). Lost housing, lost safety: Survivors of domestic violence experience housing denials and evictions across the country. Lawyers Working to End Homelessness. Retrieved from http://www.nlchp.org/content/pubs/NNEDV-NLCHP_Joint_Stories%20_February_20072.pdf

This article says a lot about the effects of leaving an abusive home and the difficulties of putting victims lives back together so that they can move on. It looks in depth at the effects of being homeless after fleeing an abusive home and problems that victims face in finding housing. The study showed that difficulty in finding housing was a national trend. The National Law Center on Homelessness and Poverty conducted a survey in order to determine the hardships that most affected the population.Weiser, W.R., &Boehm, G. (2002). Housing discrimination against victims of domestic violence. Journal of Poverty Law and Policy. Retrieved from http://www.legalmomentum.org/assets/pdfs/housingdiscriminationclearinghouse.pdf

This article explained, from a legal standpoint, that a victim of domestic violence is entitled to the right of housing. It says that a victim may not be denied housing by a landlord because of her domestic violence situation or based on the fact that she is a victim of domestic violence. The article gives examples from actual legal cases where there was discrimination involved. Although the legal aspects were not directly related to the research for this project, they did provide insight into housing discrimination of victims of domestic violence.Websites

Creative Communications Group. (2009). Definition of domestic violence. Retrieved from http://www.domesticviolence.org/

This website sponsored by Creative Communications Group provided a lot of basic information about domestic violence, signs of abuse, how abuse starts, and the cycle of violence. It helped to understand what victims are experiencing and how best to solve problems of housing.National Coalition Against Domestic Violence. (2011). Domestic violence and housing. Retrieved from http://www.ncadv.org/

This website provided a lot of facts about domestic violence in general. It also provided information about housing and domestic violence. Most of the information was straightforward facts, but these facts helped inform steps that could be taken to improve housing situations and access of victims of domestic violence.Pennsylvania Coalition Against Domestic Violence. (2004). Housing resources for domestic violence survivors and their advocates. Retrieved from http://www.pcadv.org/Resources/Housing.pdf

This article focused on housing as a critical aspect of helping victims of domestic violence get their lives back on track. It looked at connections to maintaining employment, child custody, and especially safety of the victim by removing them from the abusive situation. This article focused specifically on Pennsylvania but could be applicable to other locations as well.The Crisis Center Inc. (2011). Our services. Retrieved from http://www.thecrisiscenterinc.org/services.htm

This is the website hosted by the domestic violence organization in Manhattan, KS. It gave specific information as to the services provided by this particular program. It was important to fin out about the current situation and statistics because this organization was the focus of this study, and the program was intended to be applied there.U.S. Conference of Mayors. (2009). 2008 Status Report on Hunger & Homelessness. Retrieved from http://usmayors.org/pressreleases/documents/hungerhomelessnessreport_121208.pdf

This was a study conducted in 25 cities that reported causes of homelessness and availability of programs to support the homeless population. This study is conducted every year so by looking at previous data it is easy to see progression. In the section about homelessness the study provided trends, needs, causes, characteristics, and other important factors that have an influence on a person’s housing situation. The study also presented all of the data collected from each city individually. Learning about different cities from all over the country helped show that homelessness is a national problem and that any program should be developed in such a way that it could be inserted into any location to improve the homeless population.

Doctoral Dissertation

Collins, J. D. (2010). Understanding help-seeking behavior of abused women: A quantitative analysis of domestic violence shelter archives (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Capella University, Minneapolis, Minnesota.

This is a dissertation from Capella University that covered the behavior of victims of domestic violence. It was only partially finished but the section that was provided was very helpful in learning about the psychological aspects of what victims experience. By understanding the psychology behind being a victim of domestic violence, the design of programs and organizations can be adjusted based on the specific needs of this population. This dissertation focused on the study of female survivors and the demographic characteristics of the group.

Unpublished Manuscripts

Pable, J. (2010). The transitional homeless shelter family experience. Unpublished manuscript, Department of Interior Design, Florida State University, Tallahassee, Florida.

This study conducted by Dr. Pable explored the experience of families in homeless shelters. It observed current conditions of a shelter then altered one room. Two families in similar situations were asked to participate. One family was given an existing room and the other was housed in the altered room. After spending a period of time in the different living situations the two families were asked to answer questions about the space. This study found that the altered room had simple changes that made a lot of difference in the comfort of the family living there. Based on the study there were many design considerations that were brought to light that improved the experience in shelter. These considerations were very helpful in developing an altered program for domestic violence organizations and shelters.Sullivan, C. M. (2011). The impact of domestic abuse victim services on survivors’ safety and wellbeing. Unpublished manuscript. Department of Psychology, Michigan State University, Lansing, Michigan.

This research conducted at Michigan State University investigated the services available to domestic violence abuse victims and the impact on their safety and wellbeing. The researcher reviewed current information in order to give a starting point. The main services that were studied were shelter housing and advocacy. Both of these services play a major part in domestic violence organizations and the success of victims who use the services. The study also took a brief look at support groups and counseling and the effect on victims. Most importantly this study looks at long-term effectiveness of those services provided. It attempted to prove that programs that are helpful in short-term situations could then go on to be helpful in long-term situations. The timeline is important to developing a program because recovering from an abusive relationship and situation takes more than just a few months; it takes years, and programs need to be prepared to support victims throughout the entire process.

|