Workplace Ergonomics: A 3-Phase Intervention at the Workplace

Rachel Van Cleave

Jenna Osseck

Ashley Hartman

Deirdra Frausto

Alaina Kramer

Truman State University

Key Words – ergonomics, workplace, needs assessment

Abstract

An ergonomics education needs assessment was conducted for a convenience sample of laborers in Northeast Missouri. Results demonstrated that the respondents possessed adequate ergonomics knowledge but did not seem to be able to apply their knowledge to their daily work tasks.

Trained ergonomics instructors, therefore, presented ergonomics intervention program educational workshops for those laborers and others who worked in jobs considered at high risk for ergonomic-related injuries. Significant increases (p<.05) in pre- to post-ergonomics knowledge were reported, and the majority of respondents also reported positive personal ergonomic behaviors in a 3-month post-intervention assessment.

Introduction

Work-related musculoskeletal disorders

Musculoskeletal disorders, or MSDs, are illness manifestations related to the nerves, tendons, and other muscles that help to support the body. MSDs can cause physical impairments such as carpal tunnel syndrome, back injuries, or other weight bearing muscle injuries (National Institute of Health, 2007). MSDs affect over 50 percent of American adults and are the leading cause of disabilities that account for 130 million patient visits to health care providers annually. In addition, MSDs cost the United States approximately $50 billion per year in related expenditures (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2011).

Work-related MSDs result from occupational activities and environmental conditions. Caused by excessive, repetitive stress, work-related MSDs can have long-lasting, disabling health and economic effects. Work-related MSDs occur when there is a mismatch between physical requirements for the job and the person’s physical ability. Potential mismatches occur when a job requires repetitive motions, heavy lifting, forceful exertion, vibrating equipment, and awkward positioning. Repeated and prolonged exposure to these risk factors increases the likelihood of an MSD (Albers & Estill, 2007).

Nearly half of work-related MSD cases occur in the manufacturing or service industry, but MSDs also affect other types of occupations, such as office workers who type and perform repetitive motions in their jobs (CDC, 2011). About 34 percent of all workplace injuries are these types of injuries. Work-related MSDs place a tremendous amount of occupational disease, economic, and social burdens on both employee and employer (Levy & Wegman, 2000). Although the exact cost to employers is unknown, on average employees who suffer from MSDs have a median of 8 days of lost-work compared to the median of 6 days for all other non-fatal injuries (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2002).

Ergonomics intervention programs

When put into practice, ergonomics is defined as adapting the worker to the work environment, ensuring that the most favorable safety and production needs are met (Levy & Wegman, 2000). Workplace ergonomics encompasses three broad domains including the physical environment, cognitive environment, and organizational environment. Cognitive ergonomics relates to the mental processes of the employee in the work environment. Organizational ergonomics is concerned with the policies and procedures at the workplace. Physical ergonomics pertains to the physiological and biomechanical strain related to physical activity. Although all three domains work collectively, physical ergonomics continues to be the primary focus of many ergonomic education models for employees (International Ergonomics Association, 2010).

Ergonomics intervention programs focusing on arranging the work environment to fit the worker, changing attitudes towards injury prevention, and educating the individual worker about the work environment may target the problems that lead to work-related MSDs (Gatty, Turner, Buitendorp, & Batman, 2002). The objective of an effective ergonomic program is to improve the overall safety and performance of employees through the application of sound workplace design and elimination of ergonomic hazards (Kirkhorn & Earle-Richardson, 2006). The benefits of workplace ergonomics intervention programs include: reductions in the number of work-related musculoskeletal disorders and their incidence rate, lost workdays, restricted workdays, absenteeism, number of repetitive strain injury insurance claims, turnover, as well as improved work productivity and quality (Goggins, Spielholz, & Nothstein, 2008; CDC, 2011).

The ergonomics intervention approach can reduce the human and economic burden of workplace injury, especially when workers gain the essential knowledge and attitudes needed about ergonomics (Carrivick, Lee, Yau, & Stevenson, 2005). The knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of workers regarding ergonomics are low in high-injury occupations and may be improved by implementing efficient interventions (Carrivick, Lee, Yau, & Stevenson, 2005). Because work-related MSDs can cause physical disability to employees and economic harm to employers, the purpose of Phase I of the project was to assess the need for an ergonomics intervention for high-risk employees in rural, Northeast Missouri.

Phase I: Ergonomics Intervention Employee Needs Assessment

Methods

Sample

After institutional IRB approval, as well as respondent consent, 94 of 110 (85%) physical plant employees on the campus of a small, Midwestern university participated in the ergonomics intervention needs assessment survey. The physical plant workers were purposively chosen based on their job responsibilities that demanded intense physical labor as well as long stretches of time at a desk that could result in MSDs. Seventy-seven needs assessment surveys of the 94 total (82%) were complete and useable. Respondents were primarily male (n = 44, 61%), Caucasian (n = 71, 92.2%), and between the ages of 41-50 years old (n = 24, 31.2%).

Instrument

A brief, written, researcher-created survey was used to assess the ergonomic knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of respondents. The assessment survey was based on review of literature as well as existing ergonomics and back injury prevention surveys relating to blue collar and office workers. Cronbach’s alpha of the instrument was 0.566. The 15-item assessment consisted of five multiple choice knowledge questions about ergonomics, risk factors for injury, and consequences of injury. Attitudes towards lifting heavy objects, asking for assistance in situations that could lead to injury, and the importance of using proper lifting methods were next assessed using five rating scale questions (5-point rating scale ranging from Strongly Agree to Strongly Disagree). Five rating scale questions (4-point rating scale ranging from Never to Always) were also used to assess how often, in a typical workday, respondents engaged in potentially dangerous tasks that could result in injury.

Procedure

The respondents completed the voluntary and anonymous assessment in the fall of 2009 during a monthly staff meeting. After completion of the assessment surveys, respondents were asked to place the survey, whether completed or not, in an envelope placed on a desk located in the front of the room. The assistant director of the physical plant then sealed the envelope and provided it to the researchers.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics, including frequencies, percentages, and measures of central tendency and dispersion were used for individual item analyses as well summated scores for knowledge and attitude scales.

Results

Ergonomics knowledge assessment

The total possible correct score for the five knowledge questions was 5 as the mean score was 4.01 (SD = 1.070). Most (n = 31, 40.3%) respondents scored 5/5, followed by 4/5 (n = 25, 32.5%), and 3/5 (n = 15, 19.5%).

Ergonomics attitude assessment

Total possible positive attitude score for the five attitude questions was 25. Mean score for the five attitude questions was 20.79 (SD = 2.424) with males scoring a mean of 21.17 (SD = 2.53) and females scoring a mean of 20.20 (SD = 2.15).

Ergonomic behavior assessment

The majority of respondents (n=51, 66.2%) reported they “Sometimes” perform reaches with arms nearly straight and that they stand stooped over, performing work with their hands located at or below the level of their knees (n=48, 62.3%). Most also reported they “Sometimes” work at a rapid pace (n=49, 63.6%), followed by 20.8% (n=16/) who reported ‘Always’ working at a rapid pace (Table 1.0).

Discussion

Although it seems most respondents demonstrated adequate ergonomics knowledge and mostly positive attitudes towards ergonomic safety, most are at least sometimes at-risk through their behaviors for common workplace injuries, possibly work-related MSDs. These at-risk behaviors reported at least “Sometimes” for the majority of respondents included: performing reaches with arms nearly straight, twisting their torso without moving their feet, standing stooped over while performing work with their hands located at or below the level of your knees, working at a rapid pace, and repeating a task that causes pain.

Even though respondents reported adequate overall knowledge and positive attitudes towards ergonomics and safety, it may not have necessarily transferred to their daily work-place behaviors. It was recommended, therefore, that an ergonomics intervention program be implemented for employees like these, in high-injury risk occupations, to improve their safety at the workplace (Carrivick, Lee, Yau, & Stevenson, 2005; Kirkhorn & Earle-Richardson, 2006). Through education about injury prevention and safety in the work environment, common workplace injuries like MSDs may be prevented (Gatty, Turner, Buitendorp, & Batman, 2002).

Phase II: Ergonomics Intervention Program Instructor Training

Because a need for ergonomics intervention programs for these high-risk employees was identified, the purpose of Phase II of the project was to train and certify 15 Health Science students at a small, Midwestern university as American Red Cross-certified Workplace Ergonomics Instructors. The train-the-trainer session primarily focused on how to teach employees to identify and reduce risk for MSDs that are frequent in their workplace.

Once certified, instructors were able to educate area employees about proper body mechanics at the workstation, which may help prevent MSDs in the workplace. During the Spring of 2010, instructors were trained during an evening session lead by an American Red Cross Instructor Trainer. The training course focused on topics such as: the definitions of ergonomics and MSDs, identifying the risk for MSDs, and how to perform prevention exercises in order to reduce risks associated with MSDs at work and at home. The training used a slide show, active learning activities, and discussion to help convey points. Upon successful completion of the training phase of the project, 15 Health Science students were certified as American Red Cross Ergonomics Instructors as evidenced by receipt of their Universal Certificate of Completion.

Phase III: Ergonomics Intervention Program- Educational Workshops for Employees

Introduction

Although the exact cost of work-related injuries is unknown, thousands of Missourians experience the adverse effects of poor workplace ergonomics. In 2001, Missouri had more than 5000 cases of non-fatal work-related cases associated with repeated trauma (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2002). In addition, the physical labor profession accounted for 30.2 percent of all recorded workplace injuries in the state (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2007). Those workers in high injury-risk occupations may be able to improve their safety at the workplace and reduce their risk for MSDs when ergonomic intervention programs are provided (Carrivick, Lee, Yau, & Stevenson, 2005).

In rural Northeast Missouri, the physical plant workers who participated in the needs assessment and US Army reservists at the local base were considered at high risk for MSDs because of the nature of their occupations and lack of any previous ergonomics trainings at their work places. Both employee groups needed to be able to lift at least 50 pounds, assume awkward positions such as when working in lawn care or as mechanics, use computers and sit at desks for part of their workday, and use equipment that causes excessive vibration such as cleaning equipment or riding in military vehicles. In addition, they had a limited time line to finish tasks, worked at an increased pace, and were exposed to poor weather conditions during many of their outdoor tasks.

Purpose

The purpose of Phase III of the project was to implement ergonomics intervention program educational workshops to improve ergonomic knowledge and assess post-intervention ergonomics behavior in these high-risk employee groups.

Methods

Sample

After institutional IRB approval, as well as respondent consent, 84 participants completed both the pre- and post-knowledge tests, while 36 participants (36/84, 43%) completed the ergonomics behavior checklist three months after completing the intervention. Both employee groups from the physical plant and local US Army Reserve Unit were purposively chosen based on their job responsibilities that demanded intense physical labor as well as desk and computer work that could result in MSDs.

Instruments

Pre-post knowledge quiz - A researcher-created, 10-question, multiple-response Ergonomics Knowledge Pre-Post Quiz was used to assess any change in ergonomics knowledge immediately before and after the educational workshops were presented. The American Red Cross’ Workplace Ergonomics workbook (American Red Cross, 2008) that was followed for the educational workshops was used as the reference text to create the questions for the pre-post quiz (Figure 1.0). Questions included: the definition of ergonomics, signs and risk factors for MSDs, correct posture and work area set-up, and use of exercise to prevent MSDs.

Table 1.0 Needs Assessment: Behavior Questions – Frequencies and Percentages

How often in a typical 8 hour work day… Always

Sometimes

Rarely

Never

Do you perform reaches with arms nearly straight?

9 (11.7%)

51 (66.2%)

16 (20.8%)

1 (1.3%)

Do you twist your torso without moving your feet?

11 (14.3%)

49 (63.6%)

16 (20.8%)

1 (1.3%)

Do you stand stooped over, performing work with your hands located at or below the level of your knees?

6 (7.8%)

48 (62.3%)

20 (26.0%)

3 (3.9%)

Do you work at a rapid pace?

16 (20.8%)

49 (63.6%)

10 (13.0%)

2 (2.6%)

Does repeating a task cause pain?

1 (1.3%)

43 (55.8%)

25 (32.5%)

8 (10.4%)

Figure 1.0 Pre-Post Ergonomics Knowledge Test

1. Ergonomics… 6. What is not a risk factor for musculoskeletal disorders? A. Studies relationships between a worker and their tasks

B. Looks at the fit between a human and an activity

C. Can help prevent musculoskeletal disorders

D. All of the above

A. Repetition of an activity

B. Poor posture

C. Your overall health

D. Taking breaks frequently at work

2. Where should you use ergonomics?

7. How often should you change your body position while working?

A. In the workplace

B. Everywhere

C. Sitting only at a desk

D. At home

A. Every hour

B. Every 20 minutes

C. Every 2 hours

D. Every 45 minutes

3. What is not a first signal of a musculoskeletal disorder developing?

8. When changing direction while working you should…

A. Swelling of a muscle

B. Tingling of a muscle

C. Constant discomfort of a muscle

D. Numbness of a muscle

A. Twist your upper body

B. Reach with your arms

C. Move your whole body

D. Lean on your elbows for support

4. Musculoskeletal disorders most frequently affect what parts of the body?

9. Proper posture includes aligning...

A. Neck and wrists

B. Eyes and back

C. Back and wrists

D. Neck and eyes

A. Ears, shoulders, and hips

B. Head, neck and shoulders

C. Ears, back, and hips

D. Shoulders and hips

5. How many inches should you keep your work within while sitting at a desk?

10. To reduce your risk of musculoskeletal disorders you should…

A. 14-18 inches

B. 6-8 inches

C. 20-24 inches

D. 1-5 inches

A. Spend a lot of money

B. Do simple exercises regularly while working

C. Work part time

D. Only work at a desk

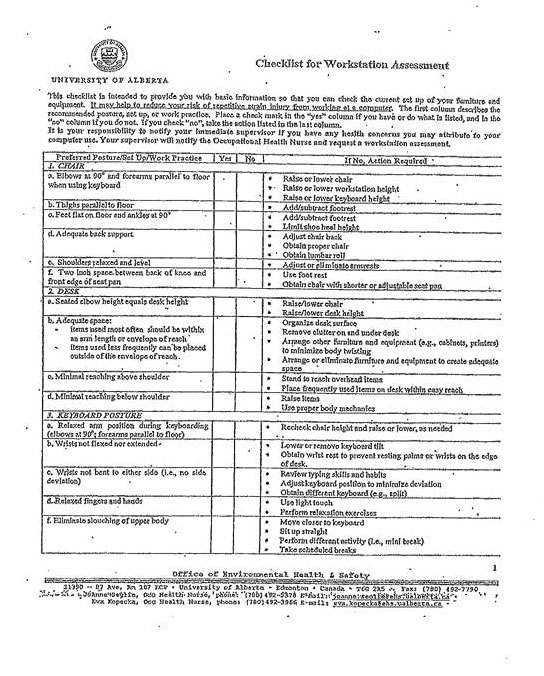

3-month post-intervention ergonomics behavior checklist

The Checklist for Workstation Assessment (University of Alberta, 2002) was used to assess participants’ ergonomics work practices three months after the educational workshops were presented (Figure 2.0). The 30-question checklist included the following topic headings with two to six questions about their ergonomic behaviors under each heading: chair position, desk set-up, keyboard posture, mouse position, monitor and document holder position, telephone position, and work and personal habits. The participants either checked ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ in response to all the questions on the checklist. A post-test was designed for assessing behavior, because collection of pre-test data was not feasible.

Figure 2.0 3-month post-intervention ergonomics behavior checklist

Table 2.0 Ergonomics behavior checklist

ITEM

YES

n(%)

NO

n(%)

SKIPPED

n(%)

A1. Elbows at 90 degrees and forearms parallel to floor when using keyboard

29(80.6)

7(19.4)

0(0)

B1. Thighs parallel to the floor

31(86.1)

5(13.9)

0(0)

C1. Feet flat on floor and ankles at 90 degrees

27(75.0)

9(25.0)

0(0)

D1. Adequate Back Support

28(77.8)

8(22.2)

0(0)

E1. Shoulders relaxed and level

32(88.9)

4(11.1)

0(0)

F1. Two inch space between back of knee and front edge of seat pan

24(66.7)

11(30.6)

1(2.8)

A2. Seated elbow height equals desk height

29(80.6)

6(16.7)

1(2.8)

B2. Adequate space: (1) Items used most often should be within an arm length or envelope of reach (2) Items used less frequently can be placed outside of the envelope of reach

30(83.3)

6(16.7)

0(0)

C2. Minimal reaching above shoulder

31(86.1)

5(13.9)

0(0)

D2. Minimal reaching below shoulder

32(88.9)

4(11.1)

0(0)

A3. Relaxed arm position during keyboarding (elbows at 90 degrees; forearms parallel to floor)

30(83.3)

6(16.7)

0(0)

B3. Wrists not flexed or extended

27(75.0)

9(25.0)

0(0)

C3. Wrists not bent to either side (i.e., no side deviation)

25(69.4)

11(30.6)

0(0)

D3. Relaxed fingers and hands

30(83.3)

6(16.7)

0(0)

E3. Eliminate slouching of upper body

26(72.2)

10(27.8)

0(0)

A4. Position of mouse allows for proper arm posture (i.e., arm not extended)

32(88.9)

4(11.1)

0(0)

B4. Wrists in neutral posture (i.e., no flexion, extension, nor side deviation)

28(77.8)

8(22.2)

0(0)

C4. Full arm motion used when using mouse

27(75.0)

9(25.0)

0(0)

A5. Head in neutral position

32(88.9)

4(11.1)

0(0)

B5. Monitor at arm's length

33(91.7)

3(8.3)

0(0)

C5. Upper torso relaxed against chair backrest

26(72.2)

8(22.2)

2(5.6)

D5. Document holder and monitor are equal distance from eyes

29(80.6)

7(19.4)

0(0)

E5. Document holder and monitor are at the same height

28(77.8)

8(22.2)

0(0)

F5. Glare minimized

34(94.9)

2(5.6)

0(0)

A6. Neck centered and in neutral position

27(75.0)

9(25.0)

0(0)

B6. Telephone within easy reach

32(88.9)

4(11.1)

0(0)

A7. Visual rest every 20 minutes

25(69.4)

11(30.6)

0(0)

B7. Regular stretch break

28(77.8)

7(19.4)

1(2.8)

C7. Alternate tasks once per hour

30(83.3)

6(16.7)

0(0)

D7. Personal habits

32(88.9)

4(11.1)

0(0)

Procedure

Educational workshop intervention

During Spring 2011, instructors presented hour-long ergonomics intervention program educational workshops to both groups at their work locations. At the beginning of the workshops, knowledge pre-tests were given, introductions were made, and educational booklets and handouts were distributed to the participants. Using a slide show, active-learning activities, and discussion, instructors then presented information about the definition of ergonomics, risk factors for MSDs, risk factor reduction, and correction of posture problems. Participants identified, using a risk assessment instrument, their daily activities at work and at home that were possible contributing factors for MSDs including force, repetition, duration, and the amount of recovery time a body needs. Participants next brainstormed ways to control their risk of developing an MSD by organizing their work area, using good posture, and choosing the right tools.

Instructors then lead participants in a proper workstation set-up activity as well as demonstrated several exercises for neck, head, shoulders, eyes, hands/wrists, arms, feet, and back to prevent strain and injury while sitting at a desk. Participants were actively involved in practicing the exercises under the supervision of the instructors. Lastly, participants were guided through the creation of a prevention plan to control risks. In small groups, each group was assigned a frequent job task that involved some of the main risk factors for MSDs, asked to identify the associated activity-related risks for the job task, and create a prevention plan listing the specific safety measures to reduce that risk. Group spokespersons presented the prevention plans to the class. In closing, participants were asked to share what they learned with co-workers, supervisors, and health care professionals as they try to make ergonomics a part of their daily routine, at work and at home. The knowledge post-test was given, participants were thanked for attending and participating, and three months later, the ergonomics behavior checklists were given.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics, including frequencies, percentages, and measures of central tendency and dispersion were used for individual item analyses as well summated scores for knowledge scale. An Independent sample t-test was used to assess statistical differences between the pre-post knowledge scores. The Independent sample t-test was chosen because pre-post test scores could not be matched and were hence analyzed in aggregate form.

Results

Change in ergonomic knowledge pre-post

An independent samples t-test revealed that there was a statistically significant difference between the mean scores of the Ergonomics Knowledge Pre-test (M=7.0714; S.D. = .21117) and the Ergonomics Knowledge Post-test (M=8.3571; S.D. = .17650). t(82)=-4.672, p<.05.

3-month post-intervention ergonomics behavior assessment

The majority of respondents, over 70 percent, reported positive personal ergonomic behaviors in a 3-month post-intervention assessment. Items most frequently checked on the Ergonomics Behavior Checklist (Table 2.0) include minimizing glare in their work setting (n=34, 94.9%) and keeping one’s computer monitor at an arm’s length away (n=33, 91.7). Almost 90 percent (n=32) also checked that their shoulders were relaxed with minimal reaching below the shoulder, arm and neck posture was appropriate at their computer stations, their telephones were within easy reach, and they practiced good personal habits. Almost one-third (n=11), though, practiced improper sitting and wrist bending at their workstations.

Table 2 about here

Discussion

Work-related MSDs place a significant health and financial hardship on employees and employers (Levy & Wegman, 2000) especially in the state of Missouri (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2002). Because laborers accounted for almost one-third of workplace injuries in the state (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2007) and those who type and perform repetitive motions in their jobs are at high-risk for MSDs (National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health [NIOSH], 2004), an ergonomics education needs assessment was conducted for a convenience sample of physical plant workers at a small Midwestern university. Results demonstrated that the respondents possessed adequate ergonomics knowledge but did not seem to be able to apply their knowledge to their daily work tasks. Trained instructors then presented ergonomics intervention program educational workshops for physical plant workers and US Army Reservists in Northeast Missouri who worked in jobs considered at high risk for MSDs because of physical labor and deskwork requirements. Significant increases in pre- to post-ergonomics knowledge were reported by respondents, and the majority of respondents noted positive personal ergonomic behaviors in a 3-month post-intervention assessment.

Ergonomics intervention programs that focus on knowledge and attitude change can be effective in reducing work-related MSD risk (Gatty, Turner, Buitendorp, & Batman, 2002). In this study, educational workshop intervention program participants significantly increased their knowledge of ergonomics, possibly leading to reduced MSD risk at their work setting. When employees increase their knowledge of ergonomics, it seems that injuries and insurance claims decrease (Carrivick, Lee, Yau, & Stevenson, 2005). In the future, this type of educational workshop intervention may also lead to improved safety statistics as well and financial savings at these work settings.

Most workplace ergonomics interventions also emphasize the physical environment (International Ergonomics Association, 2000) and hazard reduction (Kirkhorn & Earle-Richardson, 2006), similar to the intervention used in this study. The current intervention program focused on decreasing the risk of certain occupational activities such as repetitive motions and awkward positions that increase the likelihood of an MSD (Albers & Estill, 2007). Those intervention programs that also address workstation physical arrangement have been linked to decreased risk of MSDs (Gatty, Turner, Buitendorp, & Batman, 2002). Upon follow-up, the majority of respondents did report proper workstation and computer station ergonomic behaviors. The educational workshop intervention presented in this study promoted correct workstation posture and good work habits in order to prevent strain and discomfort. Participants also created a prevention plan that helped them think about ways to control future risks through identification, assessment, risk reduction, and risk monitoring. The leading contributors to the problem may best be addressed when interventions combine education, attitude change, and behavior change, (Gatty, Turner, Buitendorp, & Batman, 2002).

Although the results of this study can be used to tailor future ergonomic intervention programs, various limitations must be noted. The instruments used to assess knowledge and behavior regarding ergonomics had not undergone validity or reliability testing. Also, the post-test only design used for behavior analysis does not adequately assess whether the behavior was a result of the intervention alone. Further studies need to be conducted to determine the success of the intervention. In addition, the subjects for this study were selected from a single geographic location, therefore compromising generalizability.

Effective workplace ergonomics interventions to reduce risk factors and improve work habits can improve employee safety and work performance (Kirkhorn & Earle-Richardson, 2006). Employers can emphasize this ergonomics approach: an approach that can help reduce the burden of workplace injury, especially when high-risk workers acquire essential ergonomic knowledge (Carrivick, Lee, Yau, & Stevenson, 2005). As rationale for implementing these types of interventions, decreased absenteeism, decreased insurance claims, and increased productivity can be highlighted as benefits to the employer, and stressing reduced injuries and improved work environment can be highlighted as benefits to the employee (Goggins, Spielholz, & Nothstein, 2008; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011).

References

Albers, J. T., & Estill, C. F. (2007). Simple Solutions: Ergonomics for Construction Workers. Cincinnati, OH: NIOSH-Publications Dissemination.

American Red Cross (2008). Ergonomics. Yardley, PA: Staywell Publishers.

Carrivick, P., Lee, A., Yau, K., & Stevenson, M. (2005). Evaluating the effectiveness of a participatory ergonomics approach in reducing the risk and severity of injuries from manual handling. Ergonomics, 48(8), 907-914.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2011). Workplace Health Promotion. Retrieved August 2, 2011 from: http://www.cdc.gov/workplacehealthpromotion/evaluation/topics/disorders.html

Gatty, C. M., Turner, M., Buitendrop, D. J., & Batman, H. (2002). The effectiveness of back pain and injury prevention programs in the workplace. WORK, 20(3), 257-266.

Goggins, R. W., Spielholz, P., & Nothstein, G. L. (2008). Estimating the effectiveness of ergonomics interventions through case studies: Implications for predictive cost-benefit analysis. Journal of Safety Research, 39(3), 339-344.

International Ergonomics Association (2010). What is ergonomics. Retrieved July 23, 2011, from http://www.iea.cc/01_what/What%20is%20Ergonomics.html

Kirkhorn, S. & Earle-Richardson, G. (2006). Repetitive motion injuries. Agricultural Medicine: A practical guide, 324-338.

Levy, B.S. & Wegman, D.H. (Eds.). (2000). Occupational health: Recognizing and preventing work-related disease and injury. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

National Institute of Health (2007). News in health: Don’t let back pain get you down. Retrieved July 23, 2011, from http://newsinhealth.nih.gov/2007/January/docs/01features_02.htm

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (2004). Musculoskeletal disorders. In Worker Health Chartbook 2004 (2). Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2004-146/ch2/ch2-6.asp.htm

University of Alberta (2002). Checklist for workstation assessment. Edmonton, Canada: Office of Environmental Health and Safety.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2002). Incidence rates of nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses by industry and case types, 2002 (Data File). Retrieved from www.bls.gov/iif/oshwc/osh/os/ossm0013.pdf

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2007). Numbers of nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses by industry and case types, 2007 (Data File). Retrieved from www.bls.gov/iif/oshwc/osh/os/pr077mo.pdf

Acknowledgement

The training portion of this project was funded by a Project Grant from the Eta Sigma Gamma National Professional Health Education Honorary Office

Table 2.0 Ergonomics behavior checklist

Table 2.0

Ergonomics Behavior Checklist

ITEM

YES

n(%)

NO

n(%)

SKIPPED

n(%)

A1. Elbows at 90 degrees and forearms parallel to floor when using keyboard

29(80.6)

7(19.4)

0(0)

B1. Thighs parallel to the floor

31(86.1)

5(13.9)

0(0)

C1. Feet flat on floor and ankles at 90 degrees

27(75.0)

9(25.0)

0(0)

D1. Adequate Back Support

28(77.8)

8(22.2)

0(0)

E1. Shoulders relaxed and level

32(88.9)

4(11.1)

0(0)

F1. Two inch space between back of knee and front edge of seat pan

24(66.7)

11(30.6)

1(2.8)

A2. Seated elbow height equals desk height

29(80.6)

6(16.7)

1(2.8)

B2. Adequate space: (1) Items used most often should be within an arm length or envelope of reach (2) Items used less frequently can be placed outside of the envelope of reach

30(83.3)

6(16.7)

0(0)

C2. Minimal reaching above shoulder

31(86.1)

5(13.9)

0(0)

D2. Minimal reaching below shoulder

32(88.9)

4(11.1)

0(0)

A3. Relaxed arm position during keyboarding (elbows at 90 degrees; forearms parallel to floor)

30(83.3)

6(16.7)

0(0)

B3. Wrists not flexed or extended

27(75.0)

9(25.0)

0(0)

C3. Wrists not bent to either side (i.e., no side deviation)

25(69.4)

11(30.6)

0(0)

D3. Relaxed fingers and hands

30(83.3)

6(16.7)

0(0)

E3. Eliminate slouching of upper body

26(72.2)

10(27.8)

0(0)

A4. Position of mouse allows for proper arm posture (i.e., arm not extended)

32(88.9)

4(11.1)

0(0)

B4. Wrists in neutral posture (i.e., no flexion, extension, nor side deviation)

28(77.8)

8(22.2)

0(0)

C4. Full arm motion used when using mouse

27(75.0)

9(25.0)

0(0)

A5. Head in neutral position

32(88.9)

4(11.1)

0(0)

B5. Monitor at arm's length

33(91.7)

3(8.3)

0(0)

C5. Upper torso relaxed against chair backrest

26(72.2)

8(22.2)

2(5.6)

D5. Document holder and monitor are equal distance from eyes

29(80.6)

7(19.4)

0(0)

E5. Document holder and monitor are at the same height

28(77.8)

8(22.2)

0(0)

F5. Glare minimized

34(94.9)

2(5.6)

0(0)

A6. Neck centered and in neutral position

27(75.0)

9(25.0)

0(0)

B6. Telephone within easy reach

32(88.9)

4(11.1)

0(0)

A7. Visual rest every 20 minutes

25(69.4)

11(30.6)

0(0)

B7. Regular stretch break

28(77.8)

7(19.4)

1(2.8)

C7. Alternate tasks once per hour

30(83.3)

6(16.7)

0(0)

D7. Personal habits

32(88.9)

4(11.1)

0(0)

|