Defining the Causes of Educational Achievement:

The Effect of Social Capital on the Educational Achievement of Youth

Johnny De Vito

New York University

Abstract

As our economy evolves to demand a higher skilled, better-educated workforce, it is critical to discover and assess the causes of educational achievement among young people. Income level, parental involvement, community capital, race, truancy, and a number of other factors have been posed as possible determinants. Using the National Education Longitudinal Study, this research examined how social capital affects educational achievement on a high school and post-secondary level. This study concluded that high levels of social capital found in parents and communities affect educational achievement, even after accounting for income, parental education, and student attendance.

Introduction

As our economy evolves into an increasingly competitive, globalized, and ever-changing system, it demands a higher skilled and better-educated workforce. As a result, the United States must craft the constructive policies necessary to ensure a higher skilled, better-educated citizenry to meet those demands. In order to do so, it is useful to discover and understand the causes of educational achievement in this country. Scholars have posed a host of explanations for educational achievement; the debate has grown in both importance and interest. Income, race, parental involvement, community capital, and school quality are all suggested as possible determinants.

The implications for better understanding educational achievement are enormous and can contribute to the debate about educational reform. Constructive policy to foster educational achievement may stem the tide of the exacerbation of income inequality and help improve access to economic mobility. The consequences of increasing disparities in educational achievement among socioeconomic classes may also be significant, but thus far have not completely manifested themselves. One potential consequence we've witnessed is an increased "cultural disparity" between the lower and upper class. Certain behaviors among United States citizens are being exhibited less frequently in the lower class. These include, but are not limited to, marriage, church attendance, and unemployment. Criminal activity is also on the rise in the lower class.

The National Education Longitudinal Study (hereinafter referred to as "NELS") provided the data necessary to analyze what factors contributed to the educational achievement of over 10,000 youth from around the country. The survey followed individual subjects over 12 years from their start of eighth grade in 1988 to eight years out of high school in 2000. The first three follow-up questionnaires occurred every two years after the base year. Parents, teachers, and school administrators were interviewed during the second follow-up questionnaire to shed light on the respondent's community, school involvement, and family life.

The NELS is comprised of individual level, time-series data. This provided a host of information relating to each student's academic performance in high school, subsequent post-graduation pursuits, and factors influencing the individual along the way. Data from the second and third follow up questionnaires were used in analysis that helped explain what factors contributed to whether or not a senior graduated from high school as well as whether or not that senior went on to attend college.

To assess the possible causes of educational achievement, this paper examines several variables recorded during the respondent's senior year. These variables consist of family income, race, parental education level, parent's work status, and school attendance. In addition, two indexes were constructed to demonstrate social capital in the community and among the respondent's parents. There is no exact definition of social capital, but variables selected for each index either clearly demonstrate parental involvement and/or the availability of resources in a student's community.

A third index to measure social capital among the friends of the students was also used for analysis. This index is smaller in scope and receives less emphasis. The reason for use is that the index captures some of the autonomous decisions made by the student with respect to those with whom he or she chooses to associate and thus may be endogenous to educational achievement. High School diploma status and college attendance information were collected from each respondent two years after his or her anticipated graduation. These measures of educational achievement served as dependent variables.

This research discovered that no one factor could explain educational achievement, but that educational achievement was predicted by a number of factors. These factors included, perhaps obviously, a student's attendance at school, family income, parent's education level, social capital in the community, and social capital among parents.

Included in this paper is a literature review, where my research contrasts from and builds upon the most relevant scholars in the field of inequality. Authors were selected from a non-partisan spectrum and consist of liberal scholar Larry Bartels, conservative scholar Charles Murray, and independent-paternalist scholar Lawrence Mead. Following that is an overview of recent changes facing our nation's character, culture, and socioeconomic distribution, drawing from numerous relevant studies. The paper highlights increased cultural divergence among the socioeconomic classes, heightened income inequality, and large disparities in educational achievement. The data, research design, and results follow thereafter. This paper concludes with policy recommendations and potential implications for the United States.

Literature Review

Scholars seem to share very little agreement in assessing the causes of achievement. Several works focus on understanding determinants of income inequality as a means to better understand educational achievement. Princeton professor Larry Bartels' book entitled Unequal Democracy: The Political Economy of the New Gilded Age (2008) demonstrated an increase in inequality over the past thirty years. Income growth among the rich was far outpacing that of the middle class and poor. The percentage of total income held by Americans was increasingly being concentrated at the top.

Bartels was particularly dismayed with the demonstrated decline of economic mobility exhibited in the United States—in other words, the crumbling of the American Dream: "the United States already has significantly less economic mobility than Canada, Finland, Sweden, Norway … and the united States may be a less economically mobile society than Britain".1 Relative to our Western counterparts, the reality of an economically mobile "opportunity society" was hurting according to Bartels. The decline of America's intergenerational economic mobility seemed to confirm this. Over the past three decades, economic mobility among men declined for each generation.

Bartels' solutions were largely liberal in nature. He advocated more redistributive policies, progressive taxation, and a higher minimum wage. Bartels found a dismal connection between income and political influence; the power of middle and lower class people to influence policy change was in decline. Although more redistributive policies may be a part of the solution in addressing inequality, reducing gaps in educational achievement may also play a role. In order to accomplish this, constructive policies that foster the growth of social capital may contribute to reducing the gap and thereby help stem income inequality.

Conservative scholar and author Charles Murray similarly identified an increase in income inequality in the United States, but his proposed causes and solution are quite different from those posed by Bartels. Murray highlighted an increased cultural disparity between the lower, middle, and upper classes. Murray documented a decline in industriousness, marriage, and religiosity among the lower class that was not shared by citizens in the upper class. Murray also cited a "collapse of the American community" among lower class peoples. A decrease in neighborliness, civic engagement, and fraternal association contributes to an ever more pronounced diversion in the cultural aspects of the socioeconomic classes in our society. In tandem, the change in cultural and community factors among the lower class has led to a decline in his version of "social capital" and subsequently created the exacerbation of inequality.

Murray (2012) opposed government solutions, and condemned actions "when the government intervenes to help," suggesting that "it enfeebles the institutions through which people live satisfying lives".2 He advocated the de-escalation of the welfare state and imposition of responsibility in the hands of the citizenry; ostensibly this would reignite social capital. The need for improved levels of social capital is clear, but the persistent assertion that the government cannot be a constructive part of the solution deserves scrutiny.

Murray combined social capital found in communities with social capital generated by individuals. This paper treats social capital among communities and social capital found in families as separate and distinct plausible contributors to educational achievement.

Other scholars have approached understanding educational achievement in a uniquely independent way that is neither liberal nor conservative in nature. New York University professor and American Enterprise Institute scholar Lawrence Mead, III advocated a paternalist approach to understanding and improving educational achievement. He contended, "Research shows that the best way to improve student outcomes is strongly directed learning in which teachers set standards and follow up on students who fail to meet them"3. Professor Mead tapped fellow scholar Chester Finn to make the case for paternalism in education in the Brookings Institution Publication, The New Paternalism: Supervisory Approaches to Poverty (1997).

Lawrence Mead frequently cited the "cycle of disadvantage" that plagues poor families: "poor parents do not work because many were born out of wedlock, poorly parented, given inadequate healthcare and education, and otherwise are prepared for lives of failure."4 He suggested solutions that attach obligations to parents and entitlement benefits; the purpose of these obligations was to foster "social norms" among recipients. Among these social norms are strong parental involvement and school attendance. Professor Mead's proposed causes of underachievement in education are largely consistent with this research, although indicators of parental involvement are collectively referred to as "parental social capital" in this paper.

Background

The 1970s marked the beginning of significant changes in our society's government, culture, and socioeconomic breakdown. An era of rising partisanship in the 1970s continues to manifest itself today. It marks a period of cultural divergence between different classes and, perhaps most profoundly, one of heightened levels of inequality.

Certain behaviors and values are changing between the upper and lower class. For instance, since 1990 the percent of people married among the top 20 percent of income earners between the ages of 30 – 49 exhibited little decline, starting at about 85 percent and now hovering just under. On the other hand, income earners between the ages of 30 – 49 at the bottom 30 percent are married at significantly lower levels. From 1990 to now, the percent of married persons in this income range declined from 63 to 50 percent.5 Divorce rates are also significantly higher among lower income people compared to higher income people.

From 1947 – 1974, income at each socioeconomic percentile grew by roughly the same amount; income grew at a slightly higher percentage among the lower and middle classes, and at a slightly lower percentage among the upper class. Citizens at the 20th percentile had their collective incomes grow 97.5 percent, the 60th percentile at 102.9 percent and the 95th percentile at 89.1 percent over the period.

From 1974 – 2005, the tables turned dramatically. Cumulative income growth at the 20th percentile grew at 10.3 percent, the 60th percentile at 30.8 percent, and the 95th percentile at 62.9 percent.6 The effects of these changes are unclear but debate over what, if anything, to do about it seems contentious. This is evident at a grassroots level in the protests of Occupy Wall Street and on a more national level during current debates in Congress between Democrats and Republicans.

As income inequality has risen, economic mobility has fallen concurrently. An astonishing 42 percent of people born into the bottom socioeconomic quintile remain there as adults. Only 6 percent of those born into the bottom quintile ever climb to the top.7 On the other hand, 39 percent of those born into the top quintile stay there as adults. This is due, in no small part, to disparities in educational achievement between the socioeconomic classes.

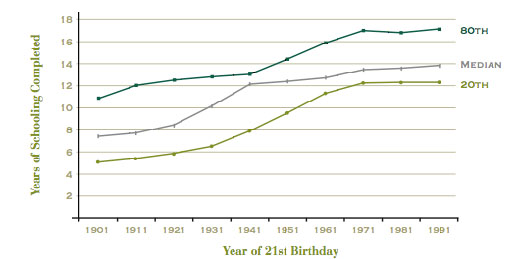

Every income percentile made steady gains in the number of education years achieved from 1941 to 1961. Thereafter, the 80th percentile took off – reaching an average of 17 years of schooling. The median percentile reached an average of 14 years of schooling and the 20th percentile flat lined at an average of 12 years of schooling.8

Years of Schooling completed by adults at the 20th, 50th and 80th income percentiles, (1900 – 2000)

Source: Fischer and Hour, 2006 pp. 11

To look at it another way, only 11 percent of youth born into the bottom quintile will have a college degree; 25 percent born at the middle quintile and 53 percent of children born at the top quintile will go on to have a college degree.9 The consequences of such huge disparities in educational achievement have yet to be fully realized but have likely contributed to our increasingly unattainable American Dream. It is possible to stem the tide but to do so it is necessary to understand the causes in order to foster constructive policy from our government and constructive action from our citizens. The data analysis found on the following pages of this paper will share some insight into the nature and causes of educational achievement.

Data

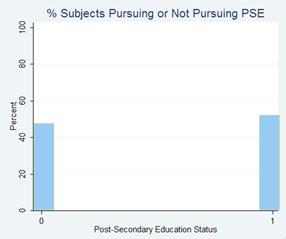

Two dependent variables serve to measure educational achievement. The first measure is whether or not the respondents were pursuing a college degree two years after their anticipated graduation. The second measure is whether or not the respondents held a high school diploma two years after their anticipated graduation. These two measures of educational achievement were selected to allow the option to assess similarities and differences with respect to the causes of high school graduation and the causes of attending college.

Several indexes representing social capital serve to test whether or not social capital contributed to educational achievement. This paper treats "social capital among parents," "social capital among communities," and "social capital among friends of the student" as distinct predictors. As a result, three indexes serve as the independent variables, with particular emphasis on the parental social capital index and the community social capital index.

The parental social capital index is composed of variables that deliberately exclude decisions made by the student. It is restricted to variables that only represent decisions made by and actions taken by the parents. This restriction rests on the assumption that parents with high levels of social capital will pass on their social capital to their children. For example, variables such as whether or not the family attends church, whether or not the parents are married, and how involved the parent is in the academic life of the student are included in this index. An in-depth explanation of the reasoning behind including each component variable in the index will follow shortly.

The community social capital index is composed of variables that identify citizen participation in the community, resources available in the school, feelings of safety in the community, and problems afflicting the school. The questions that compose the variables were asked of teachers, parents, and school administrators. By restricting a social capital index to community-based questions, we can test the influence of a student's surroundings on his or her educational achievement. It also helps us answer the question: Does it take a village, a family, or both to improve educational achievement?

The friend social capital index is comprised of fewer variables and each question is asked directly of the student. The variables ask about certain behaviors among the respondent's friends and the utility placed on being with friends. The friend social capital index helps to shed light on the influence of factors that are solely the choice of the student upon his or her educational achievement. It is plausible that the people a student chooses to associate with could have a positive or negative impact on his or her educational experience; these associations are by and large out of the parents' hands.

In my analysis, I also control for a number of variables that are suggested in other works of literature as possible determinants of educational achievement. Those include the race of the respondent, income level of the respondent, work status of the respondent's parents, education level of the respondent's parents, and school attendance by the student. Regressions were performed with and without the control variables, and each control variable identified as a significant determinant is examined to understand the size of its effect on educational achievement. Unfortunately, no variables documenting incidents of crime or violence in the community were available.

The summary statistics below show the variables in each of the indexes and which variables are used as controls.

Table 1. Summary Statistics for variables

Variables

Observations

Mean

Std. Deviation

Min

Max

Dependent Variables

Pursuing Post-Secondary Education

12003

0.522

0.5

0

1

Diploma Status Two Years after Class Graduation

12047

0.865

0.341

0

1

Independent Variables

Parental Social Capital Index

2134

0

1.677

-18.607

1.34

Family attends church

10329

0.243

0.429

0

1

Parent volunteers at school

10393

0.389

0.488

0

1

Parent attends school activities

9473

0.655

0.476

0

1

Parent involved in student's academics

3117

0.768

0.422

0

1

Parent/Student discuss activities

10464

0.943

0.25

0

1

Parent/Student discuss college

10451

0.93

0.256

0

1

Parent/Student discuss studies

10435

0.955

0.227

0

1

Parent/Student discuss grades

10435

0.974

0.16

0

1

Parent/Student discuss Troubles

10463

0.967

0.18

0

1

Parents are married

10585

0.793

0.405

0

1

Family spends time talking together

10410

0.944

0.229

0

1

Parent helps with homework

9484

0.634

0.482

0

1

Family attends social functions together

10392

0.857

0.351

0

1

Parent/Student visited colleges

7312

0.697

0.459

0

1

Family rule about homework

9313

0.79

0.407

0

1

Family rule about attendance

9321

0.906

0.292

0

1

Parent involved in the neighborhood

10490

0.778

0.417

0

1

Parent learned about financial aid

9526

0.713

0.452

0

1

Community Social Capital Index

6742

0

1.309

-6.13

2.087

Many parents attend P/T conferences

8637

0.746

0.435

0

1

Many parents volunteer at school

8613

0.23

0.421

0

1

Many parents participate in the PTA

8320

0.436

0.496

0

1

Many parents are involved in an organization

8744

0.541

0.498

0

1

The school is safe

10439

0.798

0.402

0

1

The town is safe

10510

0.942

0.235

0

1

Teachers are interested in Students

10340

0.777

0.417

0

1

School assists with applications

8990

0.998

0.408

0

1

School assists with financial aid

8992

0.996

0.065

0

1

School has a truancy/dropout program

8723

0.553

0.497

0

1

School provides a values education

8817

0.898

0.302

0

1

School promotes citizenship

8858

0.95

0.2218

0

1

Alcohol is not a problem

8863

0.932

0.252

0

1

Drugs are not a problem

8765

0.804

0.397

0

1

Teenage Pregnancy is not a problem

8850

0.649

0.477

0

1

Friend Social Capital Index

7866

0

1.3

-9.74

0.45

Drugs are not a problem among friends

10074

0.934

0.248

0

1

Grades are important to my friends

10092

0.93

0.255

0

1

High School is important to my friends

10091

0.973

0.162

0

1

I am often with friends

9995

0.889

0.315

0

1

I have few friends who dropped out

9937

0.921

0.27

0

1

Friends are important

10082

0.97

0.172

0

1

Control Variables

Asian/Pacific Islander

10544

0.056

0.23

0

1

Hispanic

10544

0.108

0.31

0

1

Black, not Hispanic

10544

0.098

0.298

0

1

White, not Hispanic

10544

0.728

0.445

0

1

American Indian/Alaskan Native

10544

0.01

0.1

0

1

Parent's work status

10330

0.767

0.423

0

1

Family income up to $25K

10194

0.328

0.45

0

1

Family income between $25-$50K

10194

0.346

0.476

0

1

Family income between $50-$100K

10194

0.25

0.433

0

1

Family income exceeds $100

10194

0.078

0.265

0

1

Parent did not complete high school

11090

0.107

0.309

0

1

Parent completed high school but no PSE

11090

0.601

0.49

0

1

Parent is a college graduate

11090

0.292

0.455

0

1

Student attends school frequently

6188

0.964

0.187

0

1

Most variables used in my research were coded as binary, "dummy" variables. The two possible values for each variable were zero and one, whereas one represents the affirmative response and zero the negative response. For example, take the variable "Parent is a college graduate": one is equivalent to yes and zero is equivalent to no. The indexes measuring social capital were each formed using a principal component analysis.

Each variable comprising the parental social capital index examined decisions made by parents that could plausibly be said to affect the family and the student. For this reason, church attendance, family participation in activities, parental involvement at the school, parental involvement in the community, and parental knowledge of financial aid were selected. The other variables that comprised the parental social capital index included direct instances of parent-student interaction. For this reason, parental involvement in the student's academic life, parent-student discussions, parent-student homework collaboration, college visitation, and family rules were chosen. In selecting these variables, it is possible to determine how social capital among the parents can directly and indirectly affect the educational achievement of the student.

The variables that comprise the community social capital index included questions that were asked of the teachers and administrators of the student's school. The few exceptions to this were the variables about community safety and teacher interest in the performance of the students; those questions were asked of the parent. The variables that measured parent-teacher conference attendance, parent volunteerism at the school, parent participation in the PTA, and parent participation in other organizations demonstrate citizen involvement in the community. The questions related to whether or not the parents felt the school and town were safe provided an idea about the relative safety of the community. The variables that indicated teacher interest, college assistance for students available in the schools, the existence of a truancy program, and whether or not the school provided educational value demonstrated resources available to the school and community. The variables that ask about alcohol, drugs, and teen pregnancy accounted for the problems afflicting the community.

The variables that compose the friend social capital index accounted for the behavior of friends and the student's feelings toward friends. Drug use among friends, importance of school among friends, and whether or not the student had many friends who dropped out indicate behavior. Whether or not the student found friends to be important and whether or not the student spent a lot of time with friends indicated the student's feelings about friends. This index received less emphasis partly because the high means suggested that there was a tendency to answer in the affirmative. The nature of these questions invited biased responses. For instance, the mean answer for "drugs are not a problem among my friends" was .934 on a scale of 0 to 1.

Research Design

The NELS offered individual level time series, cross sectional data on over 10,000 students from 1988 to 2000. Each "follow-up" survey in the study offered a cross section of students at different points in their lives. In tandem, the follow-up surveys allowed for time series or cross sectional analysis. Data measuring social capital, and all control variables, were pulled from the second follow-up of the NELS. The second follow-up was in 1992 and examined students in their senior year. This follow-up was chosen to provide the independent variables, in part, because it also offered data from a survey asked of teachers and school administrators of each student. To measure educational achievement, the third follow up was used. It took place in 1994, two years after the anticipated graduation of students.

Logistic and OLS regressions were computed to demonstrate the effect of the social capital indexes and the control variables on educational achievement. The logistic regression is ultimately more appropriate because of the binary nature of all of the variables' outcomes. Below is the logistic formula used in the research.

Yi = SCPIiSCCIi +SCFIiXi4 +i

The subscript i represents an individual student. Y represents educational achievement. Following that are the various indexes, control variables, and error terms. In addition to treating family income as a control variable, I ran regressions to assess whether or not social capital had a differing effect on educational achievement for students below and above the median income level. The beta coefficients of the OLS regressions helped to determine the relative strength of each variable on educational achievement.

Results

Below are two regressions of the main social capital indexes on the two dependent educational achievement variables. The logistic regression, being more appropriate for binary dependent variables, provides the most insight, while the OLS regression is used throughout the paper to confirm the findings of the logistic regression. This regression below demonstrates that, without control variables, the effects of parental social capital and community social capital are significant at the 5 percent and 1 percent levels.

Logit Regression OLS Regression (1) (2) Dependent Variable: Pursuing Post-Secondary Education Parental Social Capital Index 0.0840***

(0.0300)0.0165***

(0.00816)Community Social Capital Index 0.183***

(0.0445)0.0325***

(0.00816)_cons 1.249***

(0.0586)0.773***

(0.0103)N 1739 Standard errors in parentheses ="* p<0.1 ** p<0.05 *** p<0.01 Logit Regression OLS Regression (1) (2) Dependent Variable: Diploma Status Two Years after Class Graduation Parental Social Capital Index 0.1071**

(0.0464)0.0014

(0.0087)Community Social Capital Index 0.622***

(0.1472)0.006*

(0.0016)_cons 5.222***

(0.3373)0.9916***

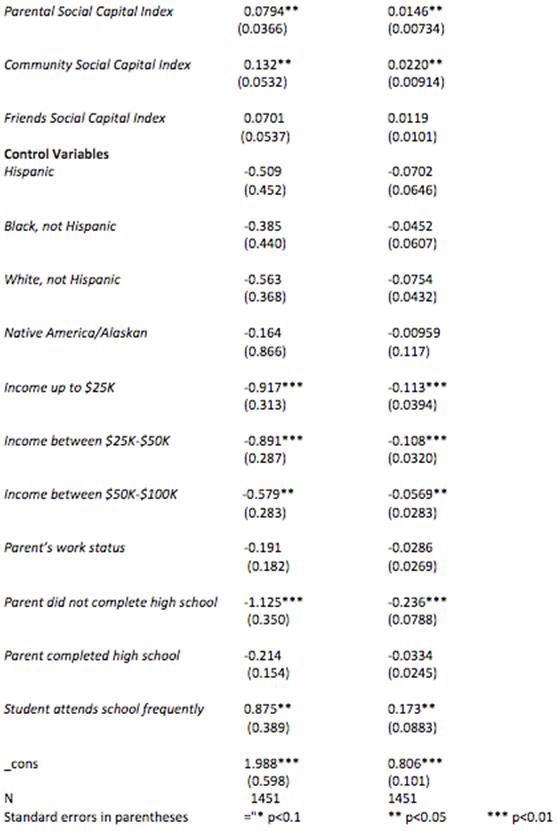

(0.0024)N 1742 Standard errors in parentheses ="* p<0.1 ** p<0.05 *** p<0.01 The following table now introduces other control variables. This dependent variable asked whether or not the student was currently enrolled in a post-secondary institution and pursuing a degree. The logistic and OLS regressions confirmed that parental social capital, community social capital, income, parent education level, and student high school attendance have a statistically significant effect on post-secondary educational achievement.

Logit Regression OLS Regression

(1) (2)

Dependent Variable: Pursuing Post-Secondary Education

Each variable was estimated relative to an omitted category. For example, income above $100K was omitted; the three other income categories had negative coefficients relative to families with income above $100K in predicting educational achievement. This was also the case for the education level of a student's parents. Parents with a college education were omitted. Parents that did not complete high school had a negative coefficient relative to parents with a college education in predicting the educational achievement of the child.

The variables that did not have a statistically significant effect on educational achievement are as interesting to discuss as those that did. Other works of literature frequently cite the disadvantages of race on educational achievement due to discrimination. These regressions seemed to suggest that, if there are disparities in educational achievement among races, they must manifest themselves in socio-economic differences that are captured by the income variables. That is to say, all other circumstances notwithstanding, outcomes in educational achievement were not affected by race.

This is not to say that racial discrimination has no negative effects for minorities in the United States. Racial discrimination can still contribute to higher levels of unemployment among Black and Hispanic citizens. Racial discrimination can also contribute to socioeconomic disparities among different races, disparities in school quality, and disparities in other determinants of educational prosperity.

Whether or not students' parents work also proved to not have a significant effect on educational achievement after high school. This seems somewhat surprising given that other literature suggests that children are impressionable by the work habits of their parents—that is to say, if a student's parents doesn't work, he or she is less likely to work and vice versa. Subsequently, one would postulate that if a child has parents that are not working, he or she would be less likely to achieve in other realms such as in education. This seemed not to be the case for post-secondary education.

Given the nature of the questions that comprise the friend social capital index, it is not terribly surprising that this index did not prove to have a significant effect. The student responses were highly skewed towards the affirmative; students may have been reluctant to be honest about the behavior of their friends. It could also be the case that friends just don't influence educational achievement after high school or that the influence of students' parents trumps that of their friends.

It is plausible that the effect of parental social capital on the educational achievement of a child may change from one level of family income to another. To better understand the true effect of social capital, it was therefore appropriate to test whether or not social capital had a stronger effect on educational achievement for lower income people relative to higher income people. To do this, the family income variable was recoded to reflect people below the median income level in one category and people above the median income level in another. People below the median income level were coded as 1 and those above the median income level were coded as zero.

The mean of the responses for this binary variable was .674, suggesting a reasonably balanced set of observations with slightly more observations below the median income level. The following table demonstrates that social capital exhibited in a student's parents has a stronger effect on students below the median income level than students above the median income level.

We expected this result because students with high incomes levels are likely to have greater access to certain educational resources relative to their counterparts: money for college, preparatory classes, and extracurricular activities, for example. In addition, students with high income were more likely to have better access to health care, nutritious food, and live in safer communities. High levels of social capital among lower income parents helped make up for the resource disparity. Parents with high levels of social capital encouraged hard work in school, engaged in volunteerism, educated themselves about college, and had serious discussions with their children. These behaviors are what drive educational achievement among students lacking in other resources. Students model their own behavior after that of their parents. They themselves join academic clubs, volunteer, learn about college, and try hard in school. They themselves develop high levels of social capital and are thereby more likely to achieve in college. In determining which variables had a stronger effect in predicting educational achievement, the coefficients given by the OLS regression provided greater ease of interpretation. I converted family income and parental education level into three level categorical variables. The categorical variable for family income was coded in three increments: 1 was equal to lower income earners, 2 was equal to mid-range earners, and 3 was equal to high income earners. The categorical variable for parent education was coded as 1 for lack of high school completion, 2 for diploma or GED, 3 for some college, 4 for college graduation, 5 for professional degree, and 6 for a PhD. Below is a table that compares the beta coefficients of each variable tested to determine educational achievement

Logit Regression

(1)Dependent Variable: Pursuing Post-Secondary Education Parental Social Capital Index -0.142

(0.0996)Community Social Capital Index 0.113**

(0.0493)Below median income* Parent SCI 0.219***

(0.105)Control Variables Below Median Income -0.388**

(0.149)Hispanic -0.399

(0.399)Black, not Hispanic -0.548

(0.388)White, not Hispanic -0.474

(0.334)Native America/Alaskan -0.512

(0.744)Parent's work status -0.236

(0.164)Parent did not complete high school -1.018***

(0.326)Parent completed high school -0.301**

(0.143)Student attends school frequently 0.860**

(0.336)_cons 1.538***

(0.487)N 1641 Standard errors in parentheses ="* p<0.1 ** p<0.05 *** p<0.01

OLS Regression With Beta Coefficients

(1)Dependent Variable: Pursuing Post-Secondary Education Parental Social Capital Index 0.0667**

(0.0074)Community Social Capital Index 0.0641**

(0.0101)Friend Social Capital Index 0.0352

(0.105)Control Variables Hispanic -0.435

(0.0646)Black, not Hispanic -0.016

(0.0602)White, not Hispanic -0.0594

(0.0431)Native America/Alaskan 0.0056

(0.1219)Family Income Level 0.0655**

(0.0185)Parent's work status -0.0282

(0.0265)Parent Education Level 0.1214***

(0.001)Student attends school frequently 0.060*

(0.086)N 1451 Standard errors in parentheses ="* p<0.1 ** p<0.05 *** p<0.01 The beta coefficients tell the following story. Parent education level had the largest effect on educational achievement compared to all other variables. For every standard deviation increase in parent education level, there was a .1214 standard deviation increase in a student's educational achievement. Parent social capital proved to be the second largest predictor of educational achievement—each standard deviation increase in a parent's social capital yielded a .0667 standard deviation increase in the educational achievement of the child. The third, fourth, and fifth strongest determinants of educational achievement were family income level, community social capital, and student school attendance respectively.

The effect of parent education level is about double that of all other determinants. Whereas the effects of parent social capital, community social capital, income, and attendance are relatively close. There are several plausible explanations for those results. Parents with higher education levels likely placed a high value on post-secondary education and understood the process. This seemed consistent with the data recorded in the logistic regression. It stated that relative to parents who graduated college, parents who did not graduate from college have children that are significantly less likely to pursue post-secondary education. Parents without a high school degree, who may or may not understand the value of a post-secondary education, have no experience with the rigorous visitation, application, and financial aid processes.

Parents with high levels of social capital were likely to encourage a number of positive characteristics in their children but had, perhaps, a less direct impact on determining educational achievement. Parents with high levels of social capital were likely to pass on an affinity for volunteerism, a high regard for the family, and the importance of meeting obligations. A high level of social capital encouraged educational achievement indirectly, but did not necessarily demand it.

The explanation for the effect of family income on educational achievement was parallel to that of social capital. Families with higher income levels did have greater access to resources that encourage education: tutors, college savings, and extracurricular programs are among them. Families with higher income levels also tended to live around other families with high income. But access to resources was neither necessary nor sufficient in explaining educational outcomes. Ultimately, having a high level of income provided access to a good education but did not guarantee educational achievement.

To conclude, having parents with a high level of education had a larger effect on a student's educational achievement, perhaps because income and social capital were likely to predict other attributes and encouraged educational achievement indirectly.

Conclusion

Disparities in educational achievement are directly related to growing levels of income inequality in our country. The National Education Longitudinal Study made possible the analysis of behavioral factors and educational outcomes recorded of thousands of subject students and their families. Meaningful relationships between causal factors and educational achievement were subsequently discovered.

The effect of parent education level per standard deviation almost doubled that of any other variable. The reason for this may relate to the direct influence a parent's level of education may have on their child whereas social capital and income have a more indirect effect. However, in terms of creating constructive policy, the fact that a parent's education level has the largest effect on educational achievement means little. No policy can directly generate more educated parents. An increase in the number of educated parents is likely to increase the number of educated students but to have more educated parents, more educated students will have to become parents. Whereas parent education level proved to have the largest effect on determining educational outcomes, meaningful policies will likely need to be directed towards other predictors of achievement.

Logistic regressions were ultimately more appropriate for the analysis given the binary nature of each dependent outcome. OLS regressions confirmed the findings of the logistic regressions and helped in assessing the relative strength of each variable that proved to be a significant determinant of educational achievement. Ultimately, in order of relative strength, parent education level, parent social capital level, family income, community social capital level, and student attendance were determined to have a significant effect on educational achievement at the post-secondary level.

The regressions also confirmed an important non-determinant of educational achievement. Race was not found to be a significant predictor of educational achievement. Other works of literature cite race and racial discrimination in explaining disparities in achievement. If this is the case, racial disparities in educational achievement must manifest themselves in variables besides race itself, such as socioeconomic status. The main take away from this is that lower income people are less likely to achieve post-secondary education, irrespective of race, and higher income people are more likely to achieve post-secondary education, irrespective of race.

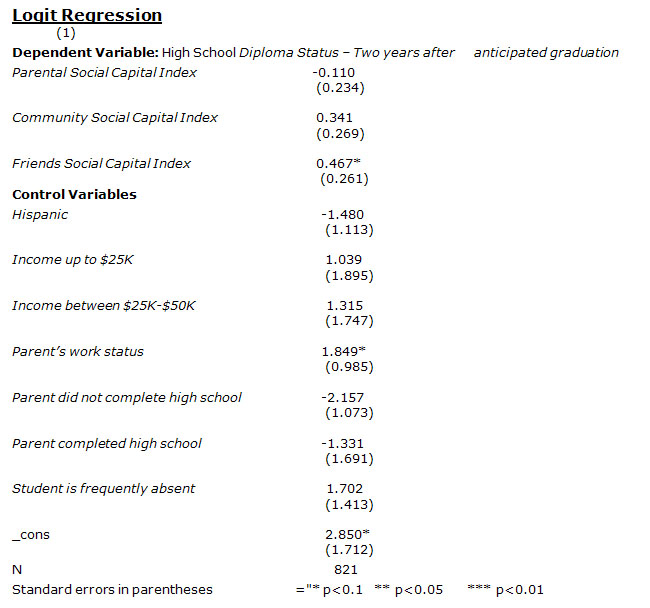

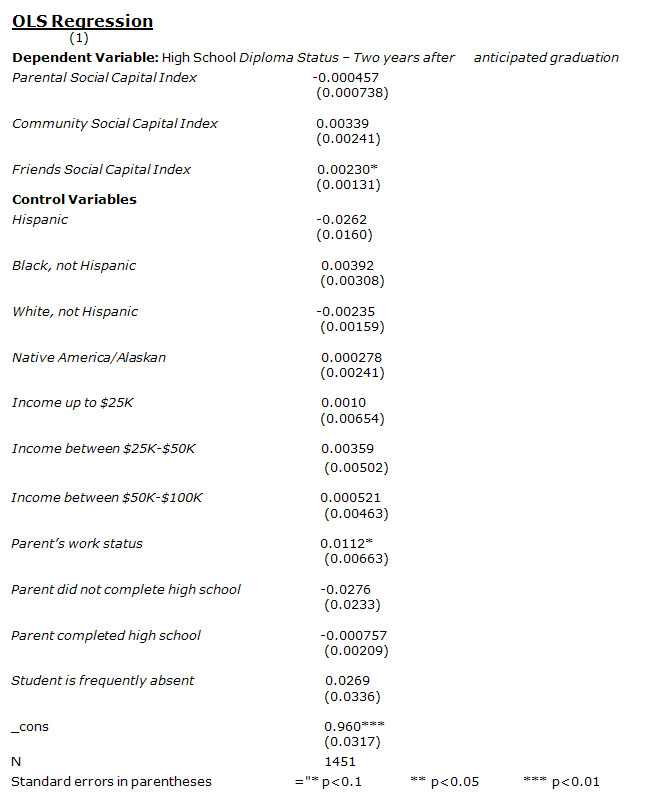

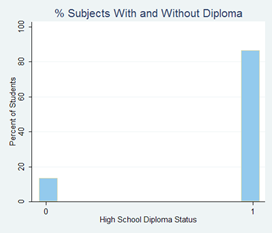

The determinants of high school graduation were less concrete and completely different from the determinants of post-secondary education. This outcome could be attributable to a number of factors. The variable for high school diploma had a lop-sided outcome in the affirmative: over 85 percent of subjects obtained a high school degree and another 4.5 percent obtained a GED by 1994, two years after their anticipated graduation. This lopsided outcome made finding common causes of achievement or lack of achievement more difficult. The results and an in-depth analysis of the determinants of high school graduation are located in the Appendix.

Friend social capital and parent work status were found to be significant at the 10 percent level in determining high school graduation. The friend social capital index is comprised of variables that measure the utility placed by a student's friends on education and whether or not those friends completed their education. It is therefore plausible that the behavior of a student's parents and friends can influence his or her high school achievement. Having parents who work and friends that place importance on education influence the student's understanding of obligation. Nonworking parents and underachieving friends negatively affect a student's understanding of obligation and subsequently whether or not they go on to graduate from high school

This research helps to contribute to the debate about educational achievement and its implications on inequality in this country. It also confirms that there is no one clear cause in predicting educational achievement. Educational achievement is instead attributable to a number of causes: income related but also behaviorally related. Parent and community behaviors, in the form of social capital, contribute significantly to the educational achievement of the students influenced.

Any politically constructive solution must therefore incorporate solutions that address behavioral and socioeconomic causes. Community capital for instance, is derived from community and school resources available to the student. Large disparities in educational resources exist between schools. This disparity is perpetuated by a system of school funding that relies on property taxes to finance a school district's operations. Lower income communities produce less revenue, and subsequently less resources are available to the school. To create more egalitarian levels of educational achievement, government investment is needed to improve the resources available to schools, especially those in lower income communities.

How to encourage parental social capital seems less clear. Charles Murray measured growing cultural divergences between socioeconomic classes, especially with respect to marriage. Constructive policy must foster strong families but much of that responsibility rests in the hands of the citizenry. Government can, however, incentivize marriage financially, hold absent parents accountable, increase access to knowledge about financial aid, and otherwise advertise positive behavior.

Income redistribution will not solve income inequality; only opportunity redistribution can do so. In addition to a more progressive tax system to make critical investments, the United States needs to equip students with the skill sets demanded of the 21st century, both in skills training and post-secondary education.

The data found in the National Education Longitudinal study is between 13 and 25 years old at this point. Since then, there have been even more pronounced cultural changes, socioeconomic changes, and technological changes that have altered the landscape of educational achievement. One possible avenue of research that I did not account for is the assessment of the effect of access to technology on achievement.

Additionally, the leisure activities that children focus their attention upon are changing. It would be interesting to research what impact the prevalence of video games and social media have on educational achievement because both now occupy a significant amount time among young people. Alternative solutions to educational achievement have also become more pronounced. Public charter schools now compete with standard public schools, and ambitious undergraduates are being sent to the lowest performing schools through Teach for America. Universities that exist solely online have emerged as an alternative to a standard college education.

In tandem, these other factors, which have been unaccounted for in the NELS, are changing the landscape of what determines educational achievement. Each represents a possible point of departure for research in this critically important problem of educational disparity in our society.

Footnotes

1. Larry M. Bartels. Unequal Democracy: The Political Economy of the New Gilded Age. (Princeton, NY: Princeton University Press, 2008) pp. 15

2. Charles Murray. Coming Apart: The State of White America 1960-2010. (New York, NY: Crown Publishing, 2012) pp. 286

3. Lawrence M. Mead, ed. The New Paternalism: Supervisory Approaches to Poverty.(Washington, DC: Brookings, 1997), pp. 33

4. Lawrence M Mead, The New Politics of Poverty: The Nonworking Poor in America. (New York, NY: Basic Books, 1992), pp. 54

5. Murray, Figure 8.3

6. Larry M. Bartels. Unequal Democracy: The Political Economy of the New Gilded Age. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2008), Figure 1.2

7. Julia B. Isaacs, Isabel V. Sawhill, and Ron Haskins. Getting Ahead or Losing Ground: Economic Mobility in America (Washington, DC: Brookings, 2008), Figure 4

8. Claude S. Fischer and Michael Hout. Century of Difference: How America Changed in the Last 100 Years. (New York: Russell Sage, 2006)

9. Ron Haskings. Education & Economic Mobility. (Washington, DC: Brookings, 2006) Figure 7

Appendix A

The dependent variable diploma status gave puzzling results. Here, parent's social capital index and the community social capital index were insignificant. The significance of each control variable was also dropped, including income and parent education level. Interpreting the results of the effect of independent variables on high school diploma achievement was difficult, given that the vast majority of subjects in the data set received their high school diploma. For example, the mean response for diploma status was 0.865 on a 0 to 1 scale. The numbers of students that did receive a high school diploma were so large that it was difficult to find common causes for failure to earn a diploma.

Roughly half the students interviewed in the study went on to pursue a college degree. It may be less difficult to assess common causes of pursuing a college degree because the balance of those observed to pursue a college degree and those observed not to allowed us to assess common predictors that influence each group's educational outcome.

The following tables demonstrate that, given all controls, only parent work status and the friends' social capital were significant variables that explained high school graduation, at least at the 10 percent level. This perplexing finding may be attributable to a number of factors.

Over 85 percent of the subjects interviewed in the NELS study received a high school diploma. Another 4.5 percent of subjects received a GED by the time they were two years out of high school. Perhaps there is no one explanation as to why over 85 percent of the subjects graduated high school, especially considering receiving a high school degree or equivalent is so common.

On the other hand, perhaps getting a high school diploma is not very difficult in most cases. Maybe social capital and family income help a little bit here and there. High schools are designed to help students graduate, so most students go on to do just that. The friends' social capital does have a significant effect on high school graduation. It is reasonable to expect that if your friends care about grades, reject drug use, and go on to graduate, it is likely to influence you to do the same. Conversely, if your friends are doing drugs, not trying in school, and dropping out, you are susceptible to mimicking those same behaviors.

The same mimicking behavior can occur with parents that work or don't work. If a student sees their parent or parents live up to the daily obligation of work, it is plausible that they will construct their own lives around the daily obligation of school. This is also plausible for non-work. If a parent does not meet their daily work obligations and proceeds to get by, why should the student?

|