Correlates of Weight Perceptions among Adolescents

Gene Oliverius,

Darlene Haff*,

Nevada State College

Keywords: Weight, Physical Activity, Adolescents

Abstract

This study of weight perceptions among adolescents used data from the 2009 Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System to analyze the bivariate relationships between self-image, depressive symptomatology, physical activity, and attempts to change perceived weight differences. Results show a statistically significant relationship between overweight perceptions and trying to lose weight, as well as relationships between feeling sad / helpless and perception of weight and between days of activity and perception of weight. The manuscript concludes with a discussion stressing the importance of education for adolescents in improving self-image.

Introduction

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2010) adolescent obesity is a serious risk to America's youth. This report indicated a prevalence of obesity among 17 percent of children ages 2-19 years. Although many studies look at the direct health implications of obesity in adolescence, the purpose of this study was to analyze the effects of self-esteem on self-perceptions of weight among adolescents. The current study analyzed secondary data from the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS) to determine if there was a significant relationship between self-esteem and perception of body weight in adolescents.

A review of the literature was conducted on the comorbidity of body image disturbance and eating disorders (Cattarin & Thompson, 1994; O'Dea and Abraham, 1999) in an attempt to emphasize the gravity of obesity with regards to self-esteem. Also, studies were examined that demonstrated the social stigmas surrounding adolescent obesity (French, Stone and Perry, 1995; Dietz, 1998; Must, 1996). Educational intervention programs were shown to increase self-esteem and improve body image (O'Dea and Abraham, 1999), and improvements in body image were shown to be beneficial for preventing eating problems, including obesity (Cattarin & Thompson, 1994). This study provided further information in an attempt to create awareness for the severity of adolescent obesity in relation to self-esteem and education in favor of improving self-esteem as a possible moderating factor to reduce adolescent obesity.

The purpose of this study was to examine the following bivariate relationships:

H1: There is a significant relationship between feeling sad / hopeless and attempts to change weight.

H2: There is a significant relationship between weight description and attempts to change weight.

H3: There is a significant relationship between current physical activity and attempts to change weight.

Literature Review

O'Dea and Abraham (1999) performed a longitudinal study of 470 adolescent students, 63 percent female ages 11-14. This study was performed to demonstrate and analyze the effects of an educational intervention program directed at improving an adolescent's body image, eating attitudes, and behaviors to improve lifestyle. Participants were randomly assigned either to a control group or an intervention group, the intervention group receiving the therapy, and then reassessed after a 12-month span. The study was successful in demonstrating that effective therapy and intervention could curb attitudes about eating disorders toward a more positive outlook, allowing students to generate a healthier body image and focus less on their physical appearance. At-risk students were of particular interest, demonstrating that control group students (those not receiving intervention) were more likely to demonstrate eating disorders and significant weight changes than those of the intervention group. This study was shown not to have any detrimental effects on the moods or behaviors of the participants. This finding lends strength to the current study, demonstrating that body image and self-image can be improved and that those features have an effect on whether an adolescent will pursue disordered eating habits.

Cattarin and Thompson (1994) performed a longitudinal study of adolescent females, retesting them after three years to examine body image disturbance, eating dysfunction, psychological functioning, and other developmental variables. Using multiple regression analyses on the data from two-hundred and ten adolescents from ages 10 to 15, data were found to support the idea that body image was a factor of later eating problems in an inverse manner. It also attributed some significance to the idea of "teasing" as being a detriment to body image, thus increasing the risk of later eating problems as well. Cattarin and Thompson also found that the entire self-image was not compromised so much as the body weight image in this relationship, leading to further studies on the subject. This study is relevant to the current study because it implied a longitudinally significant relationship between body image and eating problems that also suggested that therapy to regulate self-image would be beneficial in preventing eating problems.

French, Story, and Perry (1995) compiled an assortment of 35 studies related to self-esteem and adolescent obesity. The aim of this study was to find empirical evidence of the relationship between self-esteem and obesity in adolescents. Using a critical review of the 35 studies gathered, French et al. (1995) were able to analyze the empirically significant relationships between how self-esteem was related to obesity and whether it moderated the onset or not. French et al. (1995) found evidence that supported the idea of an inverse relationship between obesity and self-esteem, though only a moderate one. Their main criticisms revolved around the fact that studies were not consistent and that direct age comparisons could not be drawn due to the differences in methodology across studies. Also, studies did not include gender or race/ethnicity, which were listed as a possible moderating variable in the study of obesity and its relation to self-esteem. French et al. (1995) proposed future studies to examine the effect of continuous weight loss/gain and its psychological impacts, as well as studies for examining how self-esteem may moderate or increase the effects of therapy. This study gave strength to the current study because it illustrated the effects of obesity on self-esteem.

Dietz (1998) provided a critical review of literature surrounding the associated social and health consequences of childhood obesity that develops into adulthood. This study combined the research of health consequences that resulted from neglected childhood obesity with the aim to educate people how it affected health while providing possible social context. Dietz (1998) agreed that there was no agreed upon method of treatment for obesity in adolescents but that education and longitudinal studies might better illustrate the cause and effect of obesity and health consequences. The most applicable portions of this study to the current study were contained in Dietz's (1998) review of social factors associated with childhood obesity. The most striking fact that Dietz presented was that obese children do not start with a lower self-image but develop one over time as the criticism of obesity becomes more institutionalized. Dietz also pointed out that increased growth was a result of obesity, causing obese adolescents to appear more mature physically. In addition the author found that obesity lead to an increased preoccupation with weight as well as prejudices against overweight adolescents. Dietz (1998) concluded that longitudinal studies should be supplied to study these effects and monitor the actual causal effects of such stressors on the individual adolescents in order to be better equipped to deal with obesity in adolescents.

Must (1996) provided a brief literature review, analyzing documents related to the health burdens of obesity in adolescents. Her work confirmed that more studies have been consistently performed on males and less frequently on females. Must aimed to show that both long-term and short-term effects of obesity compromise health in adolescents and adults. Many of these factors are psychosocial, relating to the peer reactions, in adolescence and develop into critical health conditions during adult years. Must (1996) critically analyzed journal articles and documented studies to highlight short-term and long-term risk factors of obesity starting in adolescence. She concluded that these studies could not be used to tell exactly what risks were associated with BMI indexes and obesity health risks. This current study supports Must's conclusion wherein she promoted better nutritional choices and increased physical activity paired with less sedentary activity as an effective method to created longer, healthier lives beginning with adolescents.

Methods

The Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS) is a nationally administered survey through the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) for the purpose of assessing youth risk behavior factors. It used representative samples of students in 9th through 12th grade to determine health risk behaviors and whether those behaviors changed over time. The YRBSS also used this data to draw comparisons among youth population groups and also among national and state levels.

Measurement

This study used selected variables from the YRBSS to determine the values for reported self-esteem and self-image as well as what was done to change that image. Recent depressive symptomatology was represented by a self-report question:

During the past 12 months, did you ever feel so sad or hopeless almost every day for two weeks or more in a row that you stopped doing some usual activities? (Yes; No)

Self-esteem was represented by self-reported body image questions:

How do you describe your weight? (Very underweight; Slightly underweight; About the right weight; Slightly overweight; Very overweight)

Which of the following are you trying to do about your weight? (Lose weight; Gain weight; Stay the same weight; I am not trying to do anything about my weight)

Physical activity was represented by a self-reported physical activity question:

During the past 7 days, on how many days were you physically active for a total of at least 60 minutes per day? (Add up all the time you spent in any kind of physical activity that increased your heart rate and made you breathe hard some of the time.) (0 days; 1 day; 2 days; 3 days; 4 days; 5 days; 6 days; 7 days).

This variable's categories were collapsed as follows to meet minimum count of 5 per cell for Chi-square analysis: 0 days; 1-2 days; 3-4 days; 5-7 days.

Sample Characteristics

The YRBSS sample is described in Table 1. There are 8280 male (50.7%) and 8065 female (49.3%) students. The largest proportion of them are Caucasian (6889 students), followed by Hispanic (3037 students) and African American (2832 students). The grade levels of students are approximately evenly distributed in the range of 9th to 12th grade.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics for Socio-Demographic Variables (n = 16410)

Variables

Frequency

Percent

Gender

Male

8280

50.7

Female

8065

49.3

Hispanic

Yes

3037

18.9

No

13373

81.1

Grade Level

9th

4153

25.4

10th

3926

24.1

11th

4092

25.1

12th

4137

25.3

Other

16

.1

Race

Caucasian

6889

42.8

African American

2832

17.6

Asian/Pacific Islander

931

5.8

American Indian/Alaska Native

139

.9

________________________________________________________________________

The sample characteristics based on variables selected for hypotheses are represented in Table 2. For active days, the largest group of students (5629, 34.9%) had 5 - 7 days of activity a week while the next largest group (4014, 24.9%) had 0 days of activity per week. The remainder of students (6466, 40.1%) had between 1 - 4 days of activity. For weight distribution, the majority of students (9356, 58%) answered "About the Right Weight" with the next largest group being those that answered "Slightly Overweight" (3946, 24.5%). A large proportion of the students (7378, 45.7%) reported trying to lose weight, while the remaining categories were fairly evenly distributed. A large majority (11707, 72.1%) of students did not report feeling sadness, while 4525 students (27.9%) did.

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics for Hypotheses Variables (n = 16410)

Variables

Frequencies

Percents

Active Days

0 Days

4014

24.9

1 - 2 Days

3462

21.5

3-4 Days

3004

18.6

5-7 Days

5629

34.9

Weight Description

Very Underweight

365

2.3

Slightly Underweight

1813

11.2

About the Right Weight

9356

58

Slightly Overweight

3946

24.5

Very Overweight

643

4

Attempts to Change Weight

Lose Weight

7378

45.7

Gain Weight

2668

16.3

Stay the Same Weight

3088

18.8

Not Trying to do Anything

3017

18.4

Feeling Sad or Hopeless

Yes

4525

27.9

No

11707

72.1

________________________________________________________________________

Analysis Strategies

All hypotheses were tested using a chi-square analysis. These bivariate tests will determine if the study predictions were supported or not and if there was a significant relationship between self-esteem and obesity.

Results

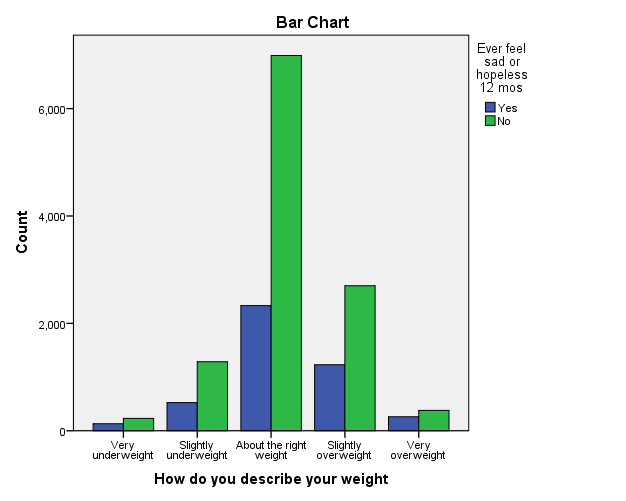

Chi-square analysis indicated a significant correlation between feeling sad / hopeless and perceptions of weight (χ2 = 125.83; p < .001). The observed values for slightly and very overweight responses were higher than expected for those adolescents feeling sad / hopeless. For adolescents who felt they were just the right weight, the observed count was lower than expected for those feeling sad / hopeless.

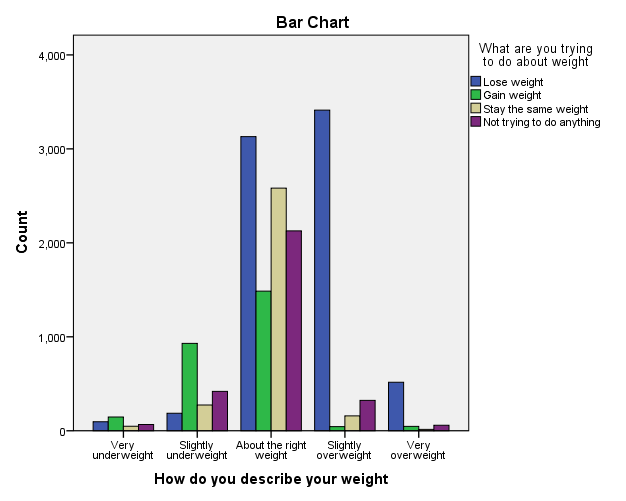

Bivariate results also showed a significant association between what one was doing about weight and perceptions of weight (χ2 = 5810.82; p < .001). Results show that almost 87 percent of adolescents who described themselves as very overweight were trying to lose weight. Those who were very overweight also reported trying to lose weight (81%). For both categories of overweight, the observed value was higher than expected.

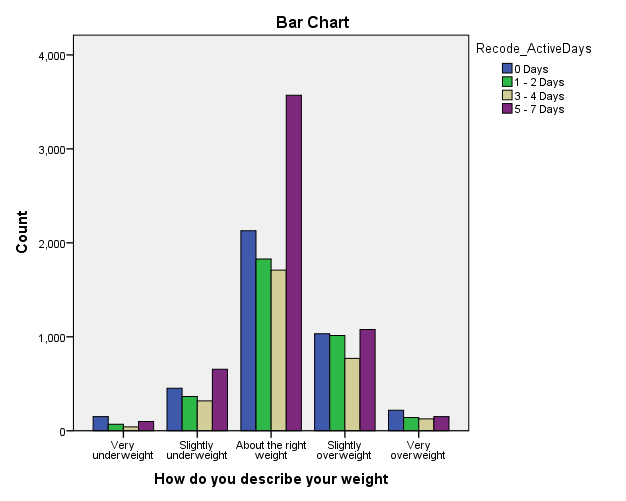

Finally, chi-square results demonstrated a significant relationship between number of days of activity and perceptions of weight (χ2 = 271.41; p < .001). For overweight categories, the observed values were higher than expected for those reporting 0 - 4 days of activity, with those reporting 5 - 7 days of activity in the overweight categories having lower than expected values. The percentages for the very overweight categories for 0 days activity were higher than for 1 or more days of physical activity.

Table 3. Chi-square Results for Weight Perceptions

Weight Perceptions

Very Underweight

Slightly Underweight

Right Weight

Slightly Overweight

Very Overweight

Sad / Hopeless

Yes

Observed

131.0

524.0

2330.0

1230.0

260.0

Expected

100.9

504.0

2596.2

1095.3

178.6

Percent

36.2

29.0

25.0

31.3

40.6

No

Observed

231.0

1285.0

6988.0

2701.0

381.0

Expected

261.1

1305.0

6721.8

2835.7

462.4

Percent

63.8

71.0

75.0

68.7

59.4

χ2 = 125.83; p<.001

Do with Weight

Lose weight

Observed

96.0

187.0

3131.0

3412.0

516.0

Expected

163.6

827.0

4261.1

1799.3

291.0

Percent

26.8

10.3

33.6

86.6

81.0

Gain weight

Observed

147.0

930.0

1486.0

44.0

47.0

Expected

59.1

298.9

1540.3

650.4

105.2

Percent

41.1

51.4

15.9

1.1

7.4

Stay same weight

Observed

48.0

274.0

2582.0

159.0

15.0

Expected

68.6

346.7

1786.4

754.3

122.0

Percent

13.4

15.1

27.7

4.0

2.4

Nothing

Observed

67.0

419.0

2127.0

323.0

59.0

Expected

66.7

337.4

1738.2

734.0

118.7

Percent

18.7

23.1

22.8

8.2

9.3

χ2 = 5810.82; p<.001

Days Active

0 Days

Observed

150.0

452.0

2128.0

1033.0

218.0

Expected

89.8

447.7

2310.2

974.2

159.1

Percent

41.8

25.3

23.0

26.5

34.3

1-2 Days

Observed

69.0

365.0

1828.0

1014.0

141.0

Expected

77.1

384.3

1982.9

836.2

136.5

Percent

19.2

20.4

19.8

26.0

22.2

3-4 Days

Observed

41.0

318.0

1709.0

770.0

126.0

Expected

66.9

333.3

1720.0

725.4

118.4

Percent

11.4

17.8

18.5

19.8

19.8

5-7 Days

Observed

99.0

655.0

3571.0

1078.0

151.0

Expected

125.3

624.6

3223.0

1359.2

221.9

Percent

27.6

36.6

38.7

27.7

23.7

χ2 = 271.41 ; p<.001

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to analyze the relationship between weight perceptions and recent depressive symptomatology, physical activity, and weight goal behaviors among adolescents. By analyzing secondary data collected in the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System, we determined the bivariate relationship between the self-image and self-perception variables by using self-reported questions from adolescents related to perceptions of body weight, activity levels, self esteem, and what adolescents were actively trying to do about their weight.

H1 stated that the more sad / helpless an adolescent reported feeling in the past year, the more likely they would report feeling overweight. This was partially supported by the chi-square analysis of the YRBSS data. It was found that there was a slightly higher count of depressed adolescents on the overweight side (1490) than on the underweight side (655). Reasons for this could be that being overweight was more socially stigmatized and therefore resulted in more negative attention towards overweight adolescents as opposed to underweight adolescents.

Figure 1. Bar Chart for Sad / Hopeless and Weight Perceptions

H2 stated that adolescents who reported trying to lose weight would be more likely to report feeling overweight. This hypothesis was strongly supported by YRBSS data. The analysis showed that while there was a significant number of adolescents in the overweight category trying to lose weight, it was the slightly overweight category that was most prevalent (3412). Adolescents in the slightly overweight category outnumbered those in the very overweight category (516) when reporting trying to lose weight. This trend might be representative of the susceptibility towards media and a general decrease in self-esteem. Within the media, adolescents strive for a projected image of shape. Lack of self-esteem may compensate for the decrease in attempts to lose weight because of the effects of social stigmatization on overweight adolescents.

Figure 2. Bar Chart for Do About Weight and Weight Perceptions

H3 stated that adolescents who reported fewer days of physical activity would be more likely to report feeling overweight. This hypothesis was partially supported by YRBSS data, with the overweight categories reporting higher numbers than the underweight categories. This was represented by the observed values of 0 - 4 days activity being higher than expected for the overweight categories. Also, the percentages of 0 days activity for the very overweight categories were much higher than for 1 or more days of activity. This may be representative of the difficulty to reassert control over physical activity after experiencing the stigmatization of being overweight.

Figure 3. Bar Chart for Physical Activity and Weight Perceptions

Limitations

The main limitation of this study was the cross-sectional design of the primary data collection. The YRBSS was a self-administered survey given to adolescents in the high school setting that obtained data from one point in time. Because of this, only correlations may be derived and there can be no causation drawn from this information. Without the use of a longitudinal study, the relationships between obesity and self-image and self-esteem can only be speculated from correlations.

Another limitation of this study was the secondary data set used. The data collected may not have represented the intended values of this study. For instance, the self-esteem values used in this study are based on one coded question: " During the past 12 months, did you ever feel so sad or hopeless almost every day for two weeks or more in a row that you stopped doing some usual activities? (Yes; No)." Because of this, the data were limited to only this scale, which was related to depression more often than self-esteem.

The YRBSS data also represented a micro study, capturing only high school level adolescents, which limits the generalizability of the study. These data were helpful in providing a representative sample of high school adolescents, but the information cannot be generalized to the larger population to explain the impact of obesity on self-image and self-esteem.

Strengths

The strengths of using the YRBSS secondary data consisted of a large, representative sample and the ability to observe multiple outcomes and exposures. The large sample of adolescents allowed for more apparent trends to be analyzed due to the spread of variables. This allowed for more reliable bivariate analysis and more observable trends.

The ability to observe multiple outcomes and exposures allowed for all hypothesis variables (perception of weight, self esteem, activity, and attempts to change weight) to be analyzed from the same set of cases. This allowed for correlations to be drawn from multiple sources to determine the accuracy of hypotheses based on relationships between the variables themselves and the stated hypotheses.

Conclusion

The relationship between self-esteem and obesity may have an impact on the functioning of adolescents. Comorbidity between self-image and eating disorders (Cattarin and Thompson, 1994; O'Dea and Abraham, 1999) illustrates the possible long-term repercussions of adolescents having to deal with the effects of obesity. It is imperative that, to avoid further complications, schools assess this situation correctly and proactively respond. The correlation between adolescents trying to lose weight and feeling overweight seems to show that there is an image that adolescents are trying to uphold about their weight. With the right education presented in schools (O'Dea and Abraham, 1999), positive influences can counteract eating problems.

The purpose of this study was to illustrate the importance of proactive reactions towards this situation. With awareness rising about the issues of obesity and health in America, it is of the utmost importance that attention is given to youth in an effort to regain control of our country's health. As shown by the study performed by O'Dea and Abraham (1999), improving body image through education can improve an adolescent's outlook without any negative repercussions. If a system that encouraged healthy eating habits were to be implemented for children in elementary school, it is possible to curb the trend towards risky eating disorders in later adolescent years.

With proper awareness of the subject, parents may also have more inclination to facilitate healthier habits for their children. Overweight or obese children often experience social scrutiny in school with little social support (Dietz, 1998). Thus, social support in schools can be expected to mitigate the negative factors associated with obesity and overweight in adolescents, and support from parents would further help to overcome the stigmatization and create a healthier lifestyle.

Ultimately, this research was meant to broaden the awareness of adolescent obesity and self-image. Implementing programs to educate children and improve their self-esteem may significantly reduce the obesity rates in America as well as improve the quality of life for many children. With proper social support from parents and schools, adolescents can overcome the societal stigmatization that evolves from being overweight.

References

Cattarin, J. A., & Thompson, K. (1994). A three-year longitudinal study of body image, eating disturbance, and general psychological functioning in adolescent females. Eating Disorders: The Journal of Treatment & Prevention, 2(2), 114-125.

Dietz, W. H. (1998). Health consequences of obesity in youth: Childhood predictors of adult disease. Pediatrics,101, 518-525.

French, S. A., Story, M., & Perry, C. L. (1995). Self esteem and obesity in children and adolescents: a literature review. Obesity Research, 3(5), 479-490.

Must, A. (1996). Morbidity and mortality associated with elevated body weight in children and adolescents. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 63, 445S-447S.

O'Dea, J. A., & Abraham, S. (1999). Improving the body image, eating attitudes, and behaviors of young male and female adolescents: A new educational approach that focuses on self-esteem. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 28, 43-57.

Ogden, C. & Carroll, M. (2010, June 4). Prevalence of obesity among children and adolescents: United states, trends 1963-1965 through 2007-2008. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/obesity_child_07_08/obesity_child_07_08.htm

|