Teachers' Context Beliefs about Implementing the CCSS

Carly Maloney

Idaho State University

Key Words: personal agency beliefs, education, Common Core State Standards, Idaho Core Standards, professional developmentAbstract

Whenever a reform takes place in the field of education, questions arise concerning implementation of the change in classrooms. The current educational shift to the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) Initiative, proposed and adopted in 45 states is no different. The CCSS were created to prepare students to become more college and career-ready in both English Language Arts and Mathematics. In preparation for teaching the CCSS, educators from districts across Idaho are and will continue to participate in professional development training, developing an understanding of what has been deemed the ICS (Idaho Core Standards)--including becoming familiar with the architecture and then creating various unit plans for implementation. The purpose of this study was to measure one part of teachers' personal agency beliefs--the context (environmental) beliefs--that might support teachers' implementation of the ICS. It was concluded that, on average, participants had high context belief scores, indicating that they believed their environments were supportive of and responsive to ICS implementation.

Introduction

Reform in education is complex and dependent upon several factors, including the quality of the professional development given to educators (Desimone, 2009; Garet, Porter, Desimone, Birman, & Yoon, 2001; Opfer & Pedder, 2011), the level of teacher motivation (Ford, 1992), and whether or not an educator's surrounding school environment is one that will respond and support him/her through the transition and implementation processes (Lumpe, Haney, Czerniak, 2000). Current reform in education in the United States comes in the form of the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) Initiative. This initiative was proposed in 2010 by the National Governors Association Center for Best Practices (NGA Center) and the Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO) and has been fully adopted by forty-five states, the District of Columbia, and four territories.

Although adopted and carried out at the state level, the CCSS were created to be a common standard that would better prepare K-12 students to become college and career-ready, to become life-long, critical thinkers, and to become capable of competing for career opportunities at an international level (National Governors Association & Council of Chief State School Officers, 2012). These clear, challenging standards exist for both English Language Arts (ELA) and for Mathematics. The CCSS for ELA were created with four main goals in mind: an inclusion of more informational-based texts, a movement towards higher literacy, a trend towards greater text complexity, and a strong collaboration between teachers of various subject areas. The CCSS for ELA are broken up into four areas: reading, writing, speaking and listening, and language; each of these areas is then broken down into either six or ten College and Career Ready (CCR) standards that are parallel in content and that increase in difficulty with each grade level. Additionally, the CCSS ELA at grades K-5 integrate literacy across disciplines, whereas the CCSS ELA in grades 6-12 separate out ELA requirements for teachers of English Language Arts and ELA requirements for teachers of science, social studies and technical subjects, although all sections stem from the same CCRs.

The CCSS for Mathematics were created with three main goals in mind: to create a national mathematics curriculum that would be more focused in nature, to create a set of standards that fit logically together, and to produce learners that would be capable of mathematical understanding and not merely mathematical knowledge. The CCSS for Mathematics are broken up into Standards for Mathematical Practice (eight standards that aim for mathematical problem solving and proficiency and for a teachable disposition in regards to mathematics) and Standards for Mathematical Content--which include understanding targets that are parallel in design, but that increase in difficulty with each ascending grade level (National Governors Association & Council of Chief State School Officers, 2012).

Literature Review

Research has shown that in order for teachers to successfully implement changes, like these CCSS, into their own classrooms, effective professional development training is needed (Desimone, 2009; Opfer & Pedder, 2011). Opfer and Pedder (2011) argued that professional development activities and research that has been found to be "ineffective" in creating learning and the power to change in teachers is that which was created with too narrow of a focus in mind, e.g., a focus on specific programs rather than a broader focus on the larger context that surrounds a teacher daily (p. 376). What has been found to be necessary for creating successful professional development programs is looking at professional development as a complex system, realizing that there are many ways to bring about professional development, and considering all three areas that impact professional development--"the teacher, the school, and the learning activities or tasks" at hand (p. 377).

In addition, Desimone (2009) recommended approaching teacher professional development utilizing a "common conceptual framework "--a framework that includes five key features: (1) a focus on content, providing teachers with activities that strengthen the content of their subject and how students can best learn that content; (2) opportunities for and experiences with active roles (3) learning that is "coherent", or that is linked to the beliefs, knowledge, and attitudes that they have already established; (4) activities and experiences that are appropriate and sufficient in duration; and (5) collaboration and participation of teachers inside and outside the same schools (p. 181-4).

The third feature of this professional development framework, the coherency between what is implemented and the teacher himself/herself, is of particular importance in implementing new reform. Consideration must be given to teachers' existing knowledge, skills, and beliefs, and how these fit into the current reform (Beck, Czerniak, Lumpe, 2000). Albert Bandura found that the decisions people make throughout their lives are most heavily dependent on what they believe (Bandura, 1977). Specifically, "self-efficacy" or how equipped one feels, how able one is to cope, and how in control one feels about accomplishing a task at hand is crucial to actually accomplishing it (Bandura, 1995). In other words, the degree to which a teacher possesses the self-efficacy to implement change largely influences whether or not, he/she is actually able to do so. However, capability may not be enough. Additional factors determine the level of motivation to implement the changes at the classroom level, even as teachers increase their knowledge, skills, and beliefs during quality professional development.

Context Beliefs

In Motivational Systems Theory (MST), Ford (1992) proposed that, in order for a person to achieve and to be competent in that achievement, he/she must be adequately "motivated", must have the appropriate "skills", and must be "biologically capable" to do what is asked (p. 70). Further, Ford (1992) defined motivation as "the organized patterning of three psychological functions that serve to direct, energize, and regulate goal-directed activity: personal goals, emotional arousal processes, and personal agency beliefs" (p. 3). He continued by proposing two types of personal agency beliefs: capability and context beliefs. The capability beliefs proposed are nearly synonymous to Bandura's concept of self-efficacy, an individual's evaluation of the existence of the needed skills to accomplish the given task (Haney, Lumpe, Czerniak, & Egan, 2002). Alternatively, context beliefs entail an individual's evaluation of the degree to which the surrounding environment is "responsive" and "supporting" in regards to the goal or task (p. 172).

Personal agency beliefs are an important component of teacher motivation, especially in terms of teachers being motivated enough to implement effective change in their classrooms. When looking at context beliefs, teachers will most likely feel more motivated to implement change in their classrooms when the environmental factors that they believe would be the most helpful are ones that are likely to occur in their schools. The context beliefs of in-service teachers were examined in this study and it was predicted that a significant difference would exist between the factors that teachers believe would best enable them to implement the CCSS (which in the state of Idaho are called the ICS or the Idaho Core Standards) and the likelihood that these factors would actually exist within their teaching environments.

Purpose

The purpose of this study was not only to identify the environmental factors that in-service teachers believe would enable them to effectively implement the ICS into their own classrooms but also to identify the environmental factors that in-service teachers believe actually exist in their schools. In addition, this study examined the differences between factors teachers believe to be enabling and factors teachers believe will be available. Lastly, this study measured the context beliefs of teachers, or how supported teachers believe they are in implementing the ICS. Predictions were made, from there, regarding the capability beliefs of these teachers and their actual implementation of the ICS.

Methods

Instrument

A 54-question survey, entitled Context Beliefs about CCSS Teaching (CBACT), was given to participants in person during an ICS professional development training. The two parts of this survey were adapted from the Context and Capability Beliefs about Teaching Science (CBATS) survey created by Lumpe, Haney, and Czerniak (2000). The first section of the survey listed 27 environmental factors and asked participants to rate the degree to which they believed these factors would enable them to teach the ICS, using a 5-point Likert scale. The second section of the survey listed the same 27 environmental factors again and asked participants to rate the degree to which they believed these factors would occur, using a 5-point Likert scale.

Participants

The participants in this study, 41 in-service teachers, were from one district in Idaho. Sixteen (16) of the 41 participants (39%) were middle school teachers of subjects other than ELA or mathematics. The remaining 25 of the 41 participants (61%) were ELA or mathematics middle school and high school teachers. The district was considered rural and 60.5 percent of students were on free and reduced lunch (Idaho State Department of Education).

These 41 in-service teaching participants were given the Context Beliefs about CCSS Teaching (CBACT) survey in person prior to an ICS professional development training led by university pedagogy experts. As was mentioned previously, the categories on the survey were adapted from the Context and Capability Beliefs about Teaching Science (CBATS) survey created by Lumpe, Haney, and Czerniak (2000) so that they addressed the environmental factors that might enable teachers to implement the ICS and that were likely to actually occur in the schools in which they teach. More specifically, in the first section, participants were presented with 27 environmental factors and were asked to report from 1 to 5 (strongly disagree to strongly agree) to which degree they believed these factors would enable them to be effective teachers of the ICS. For example, participants were asked to rate the degree to which "support from other teachers" would enable them to effectively teach the ICS. In the second section, participants were presented with the same 27 environmental factors and were asked to report from 1 to 5 (strongly disagree to strongly agree) the likelihood of these factors actually occurring. For example, participants were asked to rate the degree to which "support from other teachers" would likely occur in their schools (see Appendix A for the survey in its entirety). Each participant's ratings were summed to produce an enable score and a likelihood score for each participant. Then, the enable score which could range anywhere from 27 to 135 (the lower the number the lower the enable score, since 1=strongly disagree on our adapted Likert scale) and the likelihood score which could also range anywhere from 27 to 135 (the lower the number the lower the likelihood score, since 1=strongly disagree on our adapted Likert scale) of each participant were summed together to provide one context belief score for each participant which could range anywhere from 54 to 270 (the lower the number the lower the context belief score, since 1=strongly disagree on our adapted Likert scale).

Results

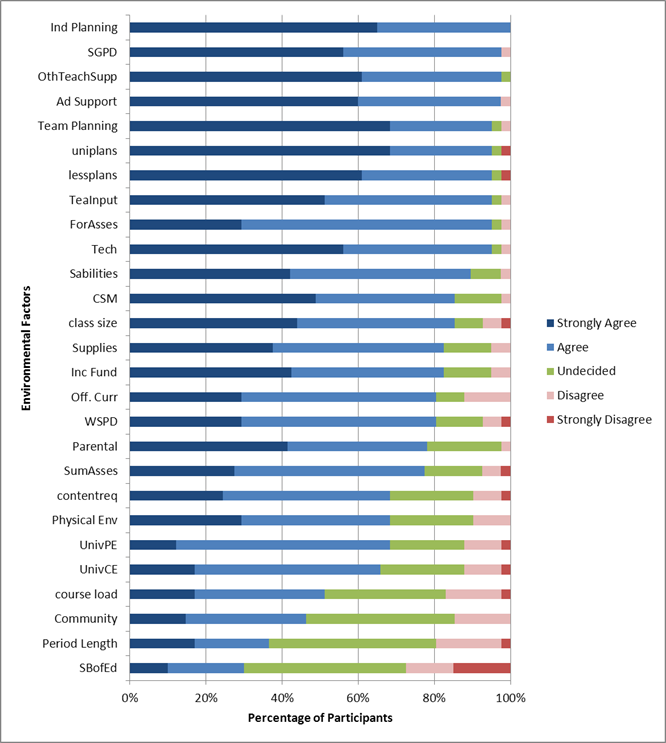

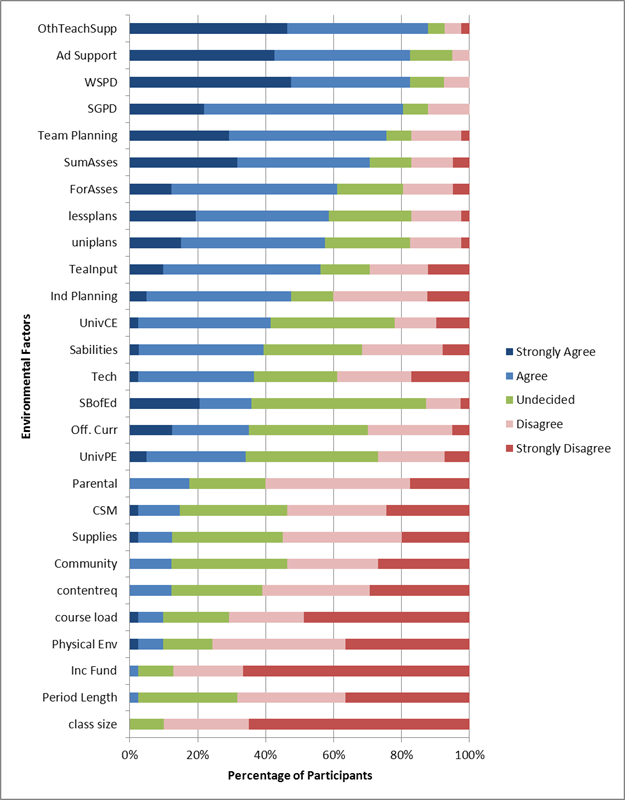

On average, the participating teachers displayed fairly positive enabling beliefs about the 27 environmental factors presented, with an average enabling score of 109.76 out of a possible 135 (see Table 1). Among the factors that participants believed would be the most enabling included individual planning time (4.65), support from other teachers (4.58), support from administrators (4.55), and small-group professional development (4.51). Some of the factors that participants believed would be the least enabling included involvement of the State Board of Education (2.98), an increase in class period length (3.32), and involvement of the community (3.46) (See Figure 1). On average, however, the participating teachers displayed less of a belief that many of the environmental factors presented to them would likely occur in their schools, with an average likelihood score of 79.15 out of a possible 135 (See Table 1). Among the factors that participants believed would be most likely to occur included support from other teachers (4.24), whole-school professional development (4.23), support from administrators (4.20), and small-group professional development (3.90). Some of the factors that participants believed would be the least likely to actually occur included a decrease in class size (1.45), an increase in funding (1.49), and an increase in class period length (1.98) (See Figure 2). On average, participants had a high context belief score, with an average context belief score of 188.90 out of a possible 270 (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Enable, Likelihood, and Context Belief Scores of Participants

Participants1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41Enable Score

130

124

113

108

107

107

84

102

110

107

109

99

112

115

109

128

104

106

100

119

100

130

120

134

115

110

122

123

91

96

108

103

111

98

121

105

113

98

111

99

99Likelihood Score

83

85

90

90

54

39

84

70

72

95

101

83

95

80

106

79

81

79

96

78

83

56

65

75

68

80

74

84

70

95

79

81

93

79

54

74

90

68

81

73

83Context Belief Score (Enable Score + Likelihood Score)

213

209

203

198

161

146

168

172

182

202

210

182

207

195

215

207

185

185

196

197

183

186

185

209

183

190

196

207

161

191

187

184

204

177

175

179

203

166

192

172

182

Figure 1. Factors Teachers Believe will and will not Enable them to Implement ICSS

Figure 2. Factors Teachers Believe are or are not Likely to Occur in their Schools

When examining the environmental factors more closely, some factors displayed large discrepancies between the participating teachers' enabling beliefs and their likelihood beliefs. For example, participants possessed much greater enable beliefs than likelihood beliefs in regards to increased funding (with a discrepancy of 2.71), decreased class size (with a discrepancy of 2.75), curriculum specific materials (with a discrepancy of 1.93), physical environment (with a discrepancy of 1.87), and parental support (with a discrepancy of 1.77) (see Table 2). As was predicted, a paired t-test revealed that participating teachers' enable beliefs (mean, 109.76) were significantly higher than their likelihood beliefs (mean, 79.15) (t=10.56; p<0.01; df=40).

54 percent of teachers indicated team planning time as one of their three most important environmental factors, 38 percent specified support from other teachers or small group professional development, and 31 percent indicated decreased class size or sample unit plans (see Table 3).

Table 2. Average Ratings of Enablement and Likelihood on Environmental Factors

Environmental Factor Enable Mean Likelihood Mean Enable - Likelihood Mean 1. Whole School PD 4.00 4.23 0.23 2. Small Group PD 4.51 3.90 0.61 3. Support from Other Teachers 4.59 4.24 0.35 4. Team Planning Time 4.61 3.85 0.76 5. Community Involvement 3.46 2.32 1.14 6. Increased Funding 4.20 4.49 *2.71 7. Period Length 3.32 1.98 1.34 8. Individual Planning Time 4.65 3.00 1.65 9. Supplies 4.15 2.40 1.75 10. Physical Environment 3.87 2.00 *1.87 11. Official Curriculum 3.98 3.13 0.85 12. Administration Support 4.55 4.20 0.35 13. Curriculum Materials 4.32 2.39 *1.93 14. Technology 4.49 2.83 1.66 15. Parental Support 4.17 2.40 *1.77 16. Student Abilities 4.29 3.03 1.26 17. State Board of Education 2.98 3.41 -0.43 18. Course Load 3.49 1.93 1.56 19. Content Required 3.80 2.22 1.58 20. Class Size 4.20 1.45 *2.75 21. University Content Experts 3.68 3.12 0.56 22. University Pedagogy Experts 3.66 3.05 0.61 23. Summative Assessments 3.95 3.80 0.15 24. Formative Assessments 4.21 3.49 0.72 25. Teacher Input in Decision Making 4.44 3.24 1.20 26. Sample Lesson Plan 4.51 3.59 0.92 27. Sample Unit Plans 4.59 3.53 1.06 Note: *=Top Five Largest Discrepancies between factors teachers feel are enabling in implementing the ICSS and factors teachers feel are likely to occur in their schools.

Table 3.

Most Preferred Environmental Factors

Environmental Factors % of Teachers who choose as top 3 4. Team Planning

3. Support from Other Teachers

2. Small Group Professional Development

20. Decreased Class Size

27. Sample Unit Plans

26. Sample Lesson Plans

11. Official School Curriculum

7. Period Length

8. Individual Planning Time

14. Technology

16. Increased Student Abilities

18. Course Load Required to Teach

19. Content Required to Teach

22. University Pedagogy Experts

24. Formative Assessments

25. Teacher Input on Decision Making54%

38%

38%

31%

31%

23%

23%

8%

8%

8%

8%

8%

8%

8%

8%

8%Discussion

As has already been discussed, the participating teachers in this study possessed fairly positive context beliefs. According to Lumpe, Haney, and Czerniak (2000) and Ford (1992), it can be assumed that these same participating teachers should also be capable of effectively implementing the ICS into their classrooms and that these same teachers likely also possess fairly positive capability beliefs. This is only an inference and can only be confirmed by conducting further studies that measure the capability beliefs or both types of personal agency beliefs (context and capability) together. For example, researchers attempting to measure the capability beliefs of teachers might administer a survey adapted from the Science Teaching Efficacy Beliefs Instrument (STEBI), which is broken up into two scales: the Personal Science Teaching Efficacy Belief scale and the Science Teaching Outcome-Expectancy scale (Riggs & Enochs, 1990). The original STEBI was developed and validated based on the idea that beliefs of teachers influence and are important to subsequent instruction. Riggs and Enochs (1990) established the STEBI as an effective self-report measure of teachers' self-efficacy because it includes both how effective teachers expect their teaching to be and how capable teachers feel about their abilities to teach the content at hand. These two researchers developed this scale particularly for elementary science instruction, but the STEBI could be adopted to fit CCSS instruction at both the elementary and secondary levels and could be used to assess the capability beliefs of teachers being asked to implement the CCSS.

In addition, a larger, more diverse sample could also be obtained. This study included a small sample of 41 participants. Larger samples might reveal a greater difference between teachers' enable scores and their likelihood scores. Participants in this study were from one district in the state of Idaho. Studies that come after this one could gather a sample from multiple districts across Idaho to ensure a more diverse population to look at other factors that might affect whether teachers are able to effectively implement the CCSS. Other studies could even measure the context beliefs of teachers in areas and states that are more urban in population. The sample used in this study was obtained from an area with fairly low socio-economic status. Future researchers might conduct a similar study in districts with higher socio-economic status, where teachers may feel they have more environmental resources available.

This study brought about insights helpful to parents, community members, educators, and administrators in southeast Idaho and across the country. Not only did findings reveal the environmental factors that teachers believe would most enable them to effectively implement the CCSS—which might help administrators and governmental officials to know where best to put educational funds and where to most fully concentrate their efforts—and this study's findings also reveal that there are discrepancies between what teachers believe will enable them, in their environments, and what they believe will actually occur. If parents knew that teachers would value their support in implementing the CCSS but felt like they were not likely to actually get their support, parents might aim to be more supportive in and out of the classroom. If community members saw that teachers would appreciate their support in implementing the CCSS but felt like they were not likely to get that community help, community members might place more funds and efforts into helping educators in their area implement the CCSS in their classrooms. As the CCSS become more and more a part of this country's education, studies—like this one—will continue to be imperative for the field of education.

References

Bandura, A. (1995). Self-efficacy in changing societies: Cambridge University Press.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84, 191-215.

Beck, J., Czerniak, C. M., & Lumpe, A. T. (2000). An exploratory study of teachers' beliefs regarding the implementation of constructivism in their classrooms. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 11, 323-343.

Desimone, L. M. (2009). Improving impact studies of teachers' professional development: Toward better conceptualizations and measures. Educational Research, 38 (3), 181-199.

Ford, M. E. (1992). Motivating humans: Goals, emotions, and personal agency beliefs: Sage Publications, Inc.

Garet, M. S., Porter, A. C., Desimone, L., Birman, B. F., & Yoon, K. S. (2001). What makes professional development effective? Results from a national sample of teachers. American Educational Research Journal, 38(4), 915.

Haney, J. J., Lumpe, A. T., & Czerniak, C. M. (2002). From beliefs to actions: The beliefs and actions of teachers implementing change. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 13(3), 171-187.

Lumpe, A. T., Haney, J. J., & Czerniak, C. M. (2000). Assessing teacher's beliefs about their science teaching context. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 37(3), 275-292.

National Governors Association & Council of Chief State School Officers (2012). Common core state standards initiative: Preparing America's students for college and career. Retrieved from http:www.corestandards.org.

Opfer, V. D. & Pedder, D. (2011). Conceptualizing teacher professional learning. Review of Educational Research, 81, 376-407.

Riggs, I. M. & Enochs, L. G. (1990). Toward the development of an elementary teacher's science teaching efficacy belief instrument. Science Education, 74(6), 625-637.

Appendix A

Informed Consent

Dear participant,

This survey is part of a collaborative effort to provide education researchers, administrators, policymakers and teachers information about the current state of teaching the Common Core State Standards/Idaho Core State Standards in your district. Responses will help focus professional development, as well as write proposals for grant funding. Your participation in this survey is voluntary and should take you approximately 20 minutes. If you choose to participate, no personal information will be collected.

The questionnaire poses no risk to you, and there is no penalty for refusal to participate. You may withdraw from the study simply by not completing the questionnaire.

The first part of the survey (adapted from Lumpe, 1990) will list 27 factors that might impact your effectiveness in teaching the Common Core State Standards (CCSS), now named the Idaho Core State Standards (ICSS) and will ask you in Column 1 to rate the degree to which you think these factors will help you be a better teacher (if they were present). Column 2 will list these same factors and ask how likely they are to occur at your school. At the end of filling out the survey, please go back and circle the three most important factors that would enable you to best implement the Idaho Core State Standards (ICSS).

If you have any questions regarding your rights as a research participant, please contact Wendy Ruchti, principal investigator, at [email protected]. For questions concerning human subjects approval, contact Idaho State University Human Subjects Committee office at http://www.isu.edu/research/hsc_intro.shtml or call 282-3371.

Beliefs about Teaching the Idaho Core State Standards (ICSS)

At the end of the survey, please circle the top three most important factors that you believe will best help you implement ICSS.

Column 1

Column 2

Environmental Factor

The following factors would enable me to be an effective teacher of the Idaho Core State Standards (SA=strongly agree; A=agree; UN=undecided; D=disagree; SD=strongly disagree)

How likely is it that these factors will occur in your school? (VL=very likely; SL=somewhat likely; N=neither; SU=somewhat unlikely; VU=very unlikely)

1. Whole-school professional staff development on teaching the Idaho Core State Standards (workshops, conferences, etc.)

SA A UN S SD

VL SL N SU VU

2. Small group professional staff development on teaching the Idaho Core State Standards (workshops, conferences, etc.)

SA A UN S SD

VL SL N SU VU

3. Support from other teachers (coaching, advice, mentoring, modeling, informal discussions, etc.)

SA A UN S SD

VL SL N SU VU

4. Team planning time with other teachers

SA A UN S SD

VL SL N SU VU

5. Community involvement in the implementation of the Idaho Core State Standards

SA A UN S SD

VL SL N SU VU

6. Increased funding

SA A UN S SD

VL SL N SU VU

7. Extended class period length (e.g., block scheduling)

SA A UN S SD

VL SL N SU VU

8. Individual planning time

SA A UN S SD

VL SL N SU VU

9. Classroom supplies/equipment

SA A UN S SD

VL SL N SU VU

10. Classroom physical environment (room size, proper furniture, etc.)

SA A UN S SD

VL SL N SU VU

11. Adoption of an official school curriculum that is aligned to Idaho Core State Standards (goals, objectives, topics, etc.)

SA A UN S SD

VL SL N SU VU

12. Support from administrators

SA A UN S SD

VL SL N SU VU

13. Curriculum specific materials (textbooks, activity books, etc.)

SA A UN S SD

VL SL N SU VU

14. Technology (computers, software, Internet, etc.)

SA A UN S SD

VL SL N SU VU

15. Parental involvement/support

SA A UN S SD

VL SL N SU VU

16. An increase in students' academic abilities

SA A UN S SD

VL SL N SU VU

17. Involvement of the state board of education

SA A UN S SD

VL SL N SU VU

18. A decrease in your course teaching load

SA A UN S SD

VL SL N SU VU

19. A reduction in the amount of content you are required to teach

SA A UN S SD

VL SL N SU VU

20. Reduced class size (number of pupils)

SA A UN S SD

VL SL N SU VU

21. Involvement of university content experts (discipline specific, e.g. English professors, biology professors)

SA A UN S SD

VL SL N SU VU

22. Involvement of university pedagogy (teaching) experts

SA A UN S SD

VL SL N SU VU

23. Classroom summative assessment strategies (End of Year/End of Course exams)

SA A UN S SD

VL SL N SU VU

24. Classroom formative assessment strategies.

SA A UN S SD

VL SL N SU VU

25. Teacher input and decisions making

SA A UN S SD

VL SL N SU VU

26. Sample lesson plans

SA A UN S SD

VL SL N SU VU

27. Sample unit plans

SA A UN S SD

VL SL N SU VU

Circle the top three most important factors that you believe will best help you implement ICSS.

|