The Importance of Ethno-Medicinal Plants amongst the Iraqw in the Karatu District: Cultural and Conservation Implications

Simmi Patel

Muhlenberg College

John Mwamhanga*

Center for Wildlife Management Studies, SFS

Keywords: Endabash area, Buger village, plant utilization, human disease, medicinal plants

Abstract

This study documents indigenous medicinal plant utilization, cultural implications, and threats affecting the survival of indigenous plants. Documenting the medicinal plants and associated indigenous knowledge can be used as a basis for future development of management plans for conservation and sustainable use of medicinal plants in the area. The study was carried out in the Karatu District, specifically in the Buger region between April 11, 2013 and April 20, 2013. Ethnobotanical data were collected using semi-structured interviews, field observations, focus group discussions, and direct matrix ranking with the village leaders on preference of medicinal plants. The ethno medicinal use of 32 plant species was documented in the study area. However, results indicated that only 30.2 percent use ethno-medicinal plants to treat human diseases. On the contrary, 98.1 percent use modern medicine (medicine from a dispensary or a hospital). The most common human diseases in the Buger region were Malaria (47%) followed by the influenza virus (also known as the common cold, 27%). Most of the medicinal plants species were collected from local gardens. Direct matrix analysis showed that Mgunga moto (Acacia mellyere), Msokoni, and Durang were the top ranked most important species used for medicine followed by Matsafi and Garmo. The factors that were tested with use of ethno-medicinal plants were gender, education level, and age class structures. Results showed that the use of ethno-medicinal plants is dependent upon education level but not on gender and age class structures. Our results showed that ethno-medicinal plant species were once a form of a traditional medicine; many have reported to prefer modern medicine over ethno-medicine. These plant species used by the people of the Buger village can be potentially threatened due to several factors, which indicate the need for attention to conservation and sustainable utilization.

Introduction

The great biodiversity in the unique environments of sub-Sahara Africa has provided indigenous cultures with a diverse range of plants that has provided an extensive knowledge of traditional medicinal purposes. Traditional medicine refers to any ancient culturally based healthcare practice different from scientific medicine and is often regarded as "indigenous, unorthodox, and/or an alternative." These practices are largely orally taught by different communities (Cotton, 1996). Given that Africa includes over 50 countries, 800 languages, and 3,000 dialects, much of the treasures in Africa lies in the knowledge and usage of medicinal plants (Simon et al., 2007). For generations, human beings have tackled disease and illness through botanical pharmacopeia that were often specific to their localities. In an ethnobotanical study conducted in Mana Angetu district, southeastern Ethiopia, ethnobotanical data were collected. The study documented 230 plant species in the area of which the majority were used for medicinal purposes. Factors limiting the conservation of medicinal plants included deforestation, agricultural expansion, fire, overgrazing, drought, and firewood. Although these factors threatened the survival of medicinal plants, several conservation practices were recommended to the people by the researchers. They promoted in-situ and ex-situ conservation of medicinal plants to ensure the survival of the plants for long term uses (Lulekal et al., 2008). In northern Kenya, the Samburu people use a wide range of ethno-medicinal resources comprising of about 120 plant species that are used to cure diseases including malaria, hepatitis, and polio (Fratkin, 1996). Although western medicine is becoming more prevalent, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported 80 percent of the world's population relies on traditional medicine (Kiringe, 2006). Similar to the Ethiopian (Lulekal et al., 2008) and then Kenyan study (Fratkin, 1996), studies were conducted in Kenya on the Maasai of Kuku Group Ranch on the ethno medicinal uses of local trees and shrubs. The study found that the Maasai utilized 24 different plant species for ethno medicinal purposes. The plants were used in high frequency however in low quantities. Most of the plants were used for multiple ailments, and all the parts of the plants (roots, barks, stems and leaves) were utilized (Kiringe & Okello, 2005). For many groups of people utilizing local trees and shrubs for ethno medicinal purposes, their current state of poverty leaves no options other than ethno-medicine. Modern facilities tend to be farther away from remote communities. Considering that medical facilities in Tanzania are relatively expensive and inconvenient, plant-based medical remedies constitute an important primary health care system. They are readily accessible and convenient for many groups like the Maasai who live in rural areas (Kiringe & Okello, 2005).

As in previous studies, so many species of plants are considered medicinal plants. Medicinal plant conservation is considered a microcosm of plant conservation as a whole. The single most important role of medicinal plants in biological conservation stems from establishing foundations that involve the local people in protecting the natural habitats of medicinal plants. The significance of medicinal plants to people can ensure conservation and sustainable uses of medicinal plants that can lay important foundations for conservation of natural habitats and ecological services. Working effectively with communities requires conservationists to have an appreciation of the cultures, economies, social structures, and dynamics of local communities in addition to understanding the biology and ecology of the plants themselves (Hamilton, 2003). Globally, contributions to human health and well-being made by medicinal plant species are widely appreciated and understood. There is growing demand for many plant species and an increasing interest in their use. This, combined with issues such as habitat loss and disconnection in traditional knowledge, is endangering medicinal plant species. According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), primary threats to medicinal plant resources in developing countries such as Tanzania includes unmonitored trade of medicinal plant resources, destructive harvesting techniques, overexploitation, and habitat loss (2001 & 2002). Most of the plants used in traditional medicine are collected from wild plants. Therefore there is concern for genetic erosion, which calls for conservation plans to ensure long-lasting uses of ethno-medicine. For rarer plant species, the IUCN recommends cultivation as an alternative to collecting wild plant species (2001). Various sets of recommendations have been compiled relating to conservation of medicinal plants: the need for coordinated conservation actions based on both in situ and ex situ strategies, inclusion of community and gender perspectives in the development of policies and programs, the establishment of systems for inventorying and monitoring the status of medicinal plants, the development of sustainable harvesting practices, encouragement for microenterprise development by indigenous and rural communities, and the protection of traditional resource and intellectual property rights (Akerele et al., 1991 & Bodeker, 2002).

In this study, uses and the importance of ethno-medicinal plants amongst the Iraqw people of Buger were investigated to identify the plant species used for treatments of different human diseases and illnesses and to assess the current situation from a conservation perspective to ensure future use of ethno-medicine. The study also aimed to investigate if plants are being used for cultural purposes and whether there are present conservation plans to ensure cultural practices for future generations. This paper aims to address the following problems concerning the uses of ethno-medicinal plants: overexploitation of wild plant species to identify the most common human diseases in the area and to assess problems in conserving plant species used for medicinal purposes.

Study Objectives:

- To study traditional knowledge on the use of plants for medicinal purposes

- To document data on plants used for ethno-medicinal purposes and its status in the Buger community forest

- To document the different human diseases that are cured with ethno-botany

- To document the usage of ethno-medicinal plants among the Iraqw of Buger village

- To identify traditional conservation practices on ethno-medicinal plants

- To recommend appropriate conservation techniques to preserve the plant species for future use

Materials and Methods

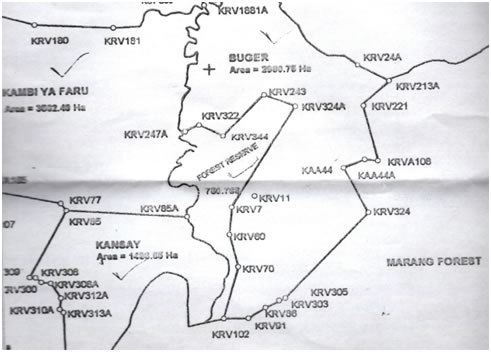

Study Area and Species studied: Bunger, Kansay, and Kambi ya Faru villages--Karatu District in the TME

The Lake Manyara Ecosystem is located at lat.3˚30'S and long.35˚40E. Surrounding the Buger, Kansay and Kambi ya Faru villages, there are several topographical landmarks such as: Lake Manyara, the Mbulu-Daudi-Endabash area, Karatu-Mbulumbululand area, the Msasa River, and the Marang Forest. In the center of the three villages, there is the shared community forest reserve. In the surrounding areas, the average annual precipitation is 650mm but can receive between 500-1000mm of rainfall. The surface waters include two types of streams and Lake Manyara: perennial streams (Yambi river drains from the Marang Forest Reserve) and seasonal streams (Endabash). There are four major soil groups in the surrounding areas: vertisols, calcimorphic, eutrophic, and ferruginous tropical soils. There are three distinctive ecological zones in the areas, which include the rift valley (lowlands), the escarpment, and the uplifted Mbulu plateau. The main vegetation includes ground water forest or riverine, Acacia woodland, thicket woodland, Alkaline grassland, Cynodon grassland, and swamp. The study area Mbulu-Daudi-Endabash Area is hilly and an undulating plateau at an elevation of 1600-2000m. Annual precipitation is 800mm, and the soils are dark red and deep clays. Vegetation is broad leafed upland forest, thorn scrub, and bushland/grassland. Land uses include large scale/subsistence farming, intensive subsistence pastoralism, forest reserve (Marang), timber harvesting, and fuel wood collection. The cultivated crops in the region include maize/corn, several legumes, sunflowers, and wheat. In order to reach this area, the team of experts needed to access the rift escarpment from the southern end of Lake Manyara towards Mubulu town. They noted that the area had steep slopes and there was evidence of overgrazing and accelerated soil erosion on the hilltops. It was also evident that there was annual burning, suggesting growth of new grass for livestock. The area had significant deforestation in the Marang Forest Reserve. Another land use that was leading to degradation was cultivation of the steep slopes, probably because there was not enough land. The edge of the Marang Forest Reserve seemed intact and the integrity of the forest was good according to the local rangers. However, the edges of the forest were facing threats from local communities for use of forest resources such as fuel wood, building materials, and other non-timber resources. Lake Manyara National Park is currently in the process of annexing the forest to be a part of the park that would significantly increase the protected status of the forest. The Marang forest also provides water catchment functions. Much of this area has been de-forested in the recent years, and the Marang Forest Reserve provides a reference of what the forest previously looked like. Lastly, overgrazing is also a major concern in the Endabash region. Majority of the people living in the area are farmers who have livestock as well as needs for farming lands. If overgrazing and over-cultivation becomes the dominant threat, there is potential to harm the ecosystem in the area (African Wildlife Foundation, 2003).

The Karatu district including the study areas: Buger, Kansay, and Kambi ya Faru villagesMethods

The study was conducted in the Buger area including the community forest and the villages along the forest borders. The study was conducted in the community forest from April 11, 2013 to April 17, 2013. The interviews were conducted in the community area from April 18, 2013 to April 20, 2013. The interviews encompassed four subvillages in Buger village: Antsi, Ayabea, Ayalaliyo, and Ayalabe. The focus group discussion took place on April 17, 2013 in the sub village of Ayalaliyo. The community forest lies in the center of three villages: Buger, Kansay and Kambi ya Faru villages. The southern end of the forest lies along the borders of Marang National forest. The species studied in the community forest included all the trees in the given plots and transects. The species studied in the interviews included all plant species listed for medicinal purposes.

In this study, the main methods that were used were: semi-structured and open-ended interviews, direct matrix ranking and focus group discussions. The household interviews were structured using the PRA (Participatory Rural Appraisal) format. The PRA technique is a versatile semi-structured process of learning from, with, and by local people (Lelo et al., 1995). Specifically household interviews were conducted randomly. The criteria for the interviews included random selection of 1 person from each household (18 years of age and older). The purpose of the household interviews was to collect socio-economic data from a cross section of farm households to gain information on different plant species used to practice ethno-medicinal techniques. These interviews provided another perspective on the current issues other than village leaders and councils. Although interviews provided substantial data, it was important to be culturally sensitive. These issues were learned through direct observations in the field. In order to allow for detailed answers, the questions asked were open-ended. The sample included households of all types (well-off and poor families, if feasible to ensure random sampling). The questionnaire included the following sections: demographic data (Name, area, age, number of people in the household, education level and employment if applicable), plant species used for medicinal purposes and what diseases are being treated with the plants, part of plant that is used, how to prepare the plant for the specific purpose of medicine (or other needs), cultural uses for the plants, water resources (distance to the water source, water access), health facilities, and agriculture related questions. Assisting the interview process, a guide who spoke the local language (Iraqw), Kiswahili, and English was assigned to every group.

Concurrent with the PRA technique, I took an applied anthropology approach to conduct interviews. Anthropology has a major influence on PRA. Classical anthropology focuses on understanding the dynamics of traditional communities. In the case of the Buger area, the anthropological approach provided information on traditional knowledge of the plants for ethno-medicinal purposes as well as any cultural implications. This ensured unbiased answers and allowed the people to answer freely and comfortably. During the 1980's applied anthropology emerged with two different approaches: the Etic and Emic approach. The Etic approach is the outsider's perspective while the Emic approach is the insider's perspective. In PRA, the focus was on the perspectives of the local people (Emic approach) rather than the outsider's perspective. PRA draws heavily on anthropological methods to gain insights of the local people. These methods included field work, interviews, focus group discussions, and placing importance on the Emic perspective. In the this study, applied anthropology with PRA provided information on types of plant species, plant uses for ethno-medicinal purposes, cultural relevance, and conservational issues (Kumar, 2002).

The second method used was focus group discussions. These discussions provided a bigger and better picture of the current issues. Often focus group discussions involve community representatives. In the focus group that was held in the subvillage of Ayalaliyo, a total of 10 community members were present. The representatives fulfilled the age set of being between 30 to 60 years old. There were eight males and two females present at the focus group discussion. The discussions provided information on community use of plant species for medicinal purposes. They also provided any communal issues with the use of plants for medicine as well as where these plants were located. During the focus group discussions, direct matrix ranking (DMR) was conducted to determine preference of certain plant species for medicine, food, honey collection, construction materials, and firewood.

Data Collection

The questionnaires were conducted in groups of 2 to 3 people with one guide who spoke Iraqw (the common language of the area), Kiswahili, and English. The guide was the key factor in the interviewing process. The guide was able to translate the answers to English for recording on the questionnaire sheets. The questionnaires were then organized on an excel spreadsheet.

Direct Matrix Ranking or "DMR" is a method that records discussions and questioning of the respondents into a table or matrix. The DMR was conducted at a focus group discussion in the subvillage of Ayalaliyo. Five categories were explored: construction, medicine, food, honey collection, and firewood. For each category, five commonly used plant species were chosen. For medicine, the five common plant species were: Mgumga Moto, Msokonoi, Durang, Matsafi, and Garmo. The direct matrix ranking was organized into a preference chart where rank and points were assigned. The interviewers asked the informants questions on preference, which were noted and eventually ranked from most preferred to least preferred.

Data Analysis

In order to analyze the data collected in the field, ethno-botanical data were entered into an Excel spreadsheet for quantitative purposes. Statistical data were generated using the SPSS program for statistical analysis. In this study, the statistics used were descriptive statistics, including cross tabulation and frequencies. This program statistically analyzes data from the interviews, including data to filter and determine frequencies of various citations such as common plant species, common diseases and ailments, popularly used medicinal plant species, and possibly to determine relationships between demographics and use of ethno-medicinal plants. The excel spreadsheet and use of SPSS documented data on plants used for ethno-medicinal purposes and their status in the Buger community forest, the different human diseases that were cured with ethno-botany, and the usage of ethno-medicinal plants among the Iraqw of Buger village. The data in the excel spreadsheets resulted in charts (pie and bar graphs) that described the frequencies of common plant species used for ethno-medicine as well as percent usage of traditional medicine and frequencies of common illnesses. The socio-economic data from household interviews were analyzed qualitatively and helped to obtain the following objectives: to identify traditional conservation practices on ethno-medicinal plants, to document the usage of ethno-medicinal plants among the Iraqw of Buger village, and to recommend appropriate conservation techniques to preserve the plant species for future use. Another statistical data analysis technique was the chi-squared test. The chi-squared test allowed comparisons between the observed and expected. The data collected determined the actual amount of ethno-medicinal plants used, and the chi-square test allowed predications on the expected amount of ethno-medicinal plants. The SPSS program determined relationships between use of ethno-medicine and demographic information such as gender, education level, and age.

Results

Ethno-medicine

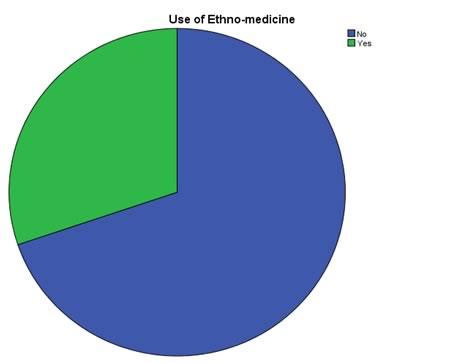

In this study a total of 106 informants were interviewed, and 32 medicinal plant species used for human diseases were documented. Amongst the 106 informants, 69.8 percent indicated that they do not use ethno-medicinal plants while 30.2 percent indicated they do use ethno-medicine (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Use of ethno-medicinal plants amongst the Iraqw in the Buger region30.2%69.8%The ethno-medicinal uses of the 32 species documented through the interviews, focus group discussions, and data collected from the community forest are cited in Table 1.

Table 1. Commonly used medicinal plants to treat human diseases in the Buger region

Number Iraqw Name Scientific Name Utilization Part of Plant Preparation 1 Aanqway N/A Malaria N/A 2 Ankwi Vernonia exsertiflora Medicine for deep cuts N/A 3 DumeMfufaru Croton microstachys Joint pain Bark and leaves N/A 4 Durang N/A PMS for women/ Malaria roots N/A 5 Eucalyptus Eucalyptus globulus Menstruation/PMS Bark Boils bark and drinks it in hot water 6 Garmo N/A Brush teeth/dental medicine N/A 7 Ghargasi N/A Birth control leaves N/A 8 Guava leaves N/A Stomach pain leaves Boil leaves in water and drink 9 Hhamandu N/A Malaria, STD's N/A Prepared by witch doctor 10 Hhangali (Sodum apple) N/A Stomach pain Fruit, leaves, bark, roots Eat roots or drink fruit juice, or boil roots and drink 11 Kiloviti (Baryomodi) Acacia nilotica Digestion (stomach) Roots N/A 12 Laayloi Stomach pain (causes diarrhea to rid body of stomach parasites) bark Grind the bark, place one teaspoon into boiling water 13 Maayangu Ximenia caffra Colds; Gonorrhea, ulcers in stomach, treats fresh cut wounds Bark, roots, leaves Grind bark into powder mixed with sandal wood and put in tea to drink; grind up roots, drink for ulcers in stomach and place boiled leaves on fresh cut wounds 14 Maslaramo Vangaena madagascaneinsis Stomach medicine Fruit, bark, leaves N/A 15 Matsafi N/A Malaria, colds Flowers for colds Smells the flower to stop his cold 16 Memiali N/A Treat skin diseases Latex liquid from tree Place the liquid on the skin 17 Mgunga Acacia spp. allergies Bark N/A 18 Mgunga Moto Acacia mellyere Stomach illness N/A Prepared by witch doctor 19 Minighiti Euclea spp. Stomach pains bark Grind up bark 20 Mori Scolopia spp. Prostate treatment/ men's health N/A 21 Morongi N/A Pneumonia and cold Bark Grind bark into powder mixed with sandal wood and maayangu and put in tea to drink 22 Msokoni N/A Colds Leaves, roots Grinds leaves and roots for tea 23 Mwarobaini (Neem tree) N/A Malaria Leaves Boils leaves and drinks water 24 Nughay Hoslundia opposite Medicine for men roots N/A 25 Qarrengei Aloe barbadensis STD's, animal disease, stomach problems, fresh cut wounds, eye pain; stomach pains Liquid, branches Can drink, apply for wounded areas; branches for stomach pains 26 Sakwanay Warbugia ugandensis Stomach pains, general pain and to wash pubic areas, pneumonia Bark Grind bark and put in hot water of porridge or tea 27 Sandal wood Osyris lanceolata Pneumonia, Malaria, STD's, chest pain; colds Roots, bark Grind up bark and roots and put in porridge/drink like tea; Grind bark into powder mixed with sandal wood and maayangu and put in tea to drink 28 Sio N/A Fractured bone pain Leaves Place leaves in hot water and place hot leaves on fracture 29 Tloqmo N/A Stomach medicine Bark Dry bark and grind it then put in porridge 30 Washawasha N/A STD's and kidney N/A 31 Xaxardu N/A Cold, cough Roots Roots are eaten raw 32 Yellow barked acacia Acacia xanthophloea Diarrhea Bark N/A The plant parts used widely for the treatment of human diseases included, bark, leaves, roots, flowers, and fruits are listed in Table 2. The most commonly used plant parts for remedy preparation were the bark (37.5%) and leaves (28.1%).

Table 2. Medicinal plant parts used by the Iraqw people for remedy preparation

Plant part used No. of Species Percent of species Bark 12 37.5% Leaves 9 28.1% Roots 8 25.0% Flowers 1 3.12% Fruit 2 6.25% Total 32 plant species ~100% From the interview data and the focus group discussions it was apparent that medicinal plants have various methods of preparation and application for different types of ailments. They commonly form concoctions that have powdered bark, leaves, or roots that are homogenized in water to form a tea or a type of porridge. The preparation and application methods vary based upon the type of disease treated and the actual site of the ailment. Different routes of application included oral, topical, or dermal routes.

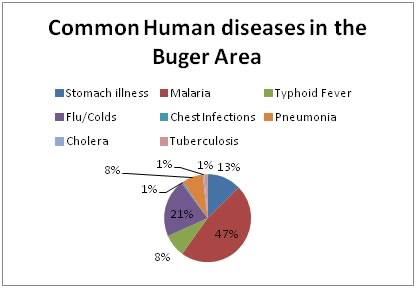

Disease types in the Buger region

The interview data (shown in Figure 2) indicate that Malaria is the most common disease (47%), followed by the common cold (21%).

Figure 2. Common human disease prevalent in the Buger regionPreference direct matrix ranking of medicinal plants used to treat human diseases

According to the matrix ranking of preferred medicinal plants used to treat human diseases, Mgunga moto (Acacia mellyere), Msokoni, and Durang were the top ranked species used for medicine followed by Matsafi and Garmo. Mgunga moto is used to treat stomach diseases and Msokoni treats common colds. Durang is used to treat PMS symptoms as well as Malaria. Matsafi is used to treat both common colds and malaria. Lastly, Garmo is used to treat dental diseases, and the bark is often used as a "toothbrush."

Cultural and socio-economic implications with the use of ethno-medicinal plants

Aside from medicinal importance, many informants in the focus group discussions mentioned that plants used for medicinal purposes were also used for other reasons such as for food, honey collection, firewood, and construction materials. The matrix ranking showed that the tree Minighiti (Euclea spp.) was preferred for construction materials. Medicinally, the bark of Minighiti was used to treat stomach diseases. Similarly, Minighiti was also used for firewood and was highly preferred amongst the people in the Buger region. Maslaramo (Vangaena madagascaneinsis), which was used to treat stomach diseases, was also used for firewood and honey collection and eaten as fruit. Msokoni is often used to treat common colds; however it can also be used for honey collection.

Factors that affect use of ethno-medicinal plants

Several factors were tested in relation to use of ethno-medicinal plants including gender, education level, and age class structures. In Table 3 (below), the percentage of males within the population using ethno-medicinal plants was 49.1 percent while the female percentage was 50.9 percent.

Table 3. Gender and use of ethno-medicinal plants

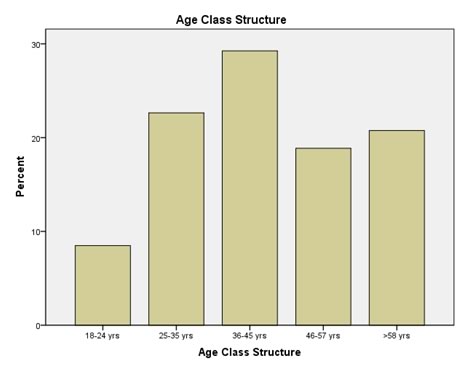

Gender Use of Ethno-medicinal plants Percentage of Use of ethno-medicinal plants Male 52 49.1 Female 54 50.9 Total: 106 interviews Amongst age class structures, the highest use of ethno-medicinal plants was between the age of 36 and 45 years old (29.2% who used ethno-medicine were between 36 and 45 years old, see figure 3).

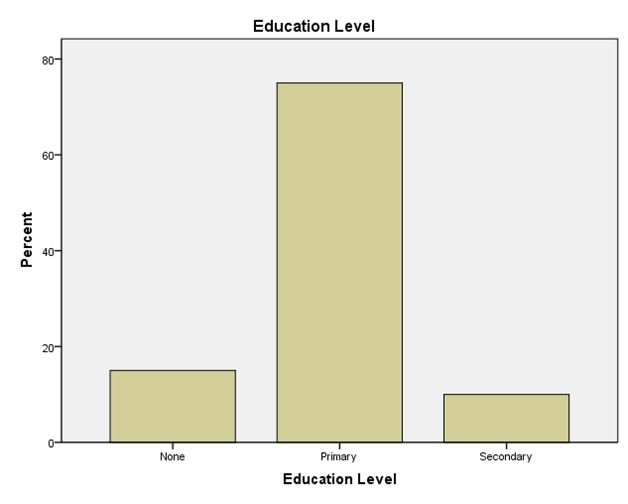

Figure 3. Age class structures and use of ethno-medicinal plants in the Buger regionAccording to education levels, the highest use of ethno-medicinal plants (traditional medicine) was amongst the people whose highest level of education was primary level (see figure 4). Between those who use ethno-medicinal plants, the percentage who achieved the highest education level at the primary level was 75 percent. The percentage who used ethno-medicinal plants that had no education was 15 percent, and those who used traditional medicine whose highest level was secondary school was 10 percent.

Figure 4. Education level and use of ethno-medicinal plants in the Buger regionA chi-square determined relationships between gender, education level, and age class structures and use of ethno-medicinal plants. The use of ethno-medicine does not depend upon age class structures (x2= 7.585, p=.108, alpha value= .05, not significant). Similarly, the use of ethno-medicine does not depend upon gender (x2= 3.315, p=0.069, alpha value= .05, not significant). However, the use of ethno-medicine depends upon education level (x2= 16.105, p=.003, alpha value= .05, significant).

Popularly medicinal plants found in the community forest

Most of the data were from questionnaires conducted in the village of Buger, several transects were completed in the community forest identifying plant species and their utilizations. Table 4 indicates the popular plants that are often used for medicinal purposes (see below). The most common plant species used for ethno-medicinal purposes was Maslaramo (Vangaena madagascaneinsis), which treats several stomach diseases.

Local plant species name (Iraqw) Scientific Name Frequency of Observation Percentage Nughay Hoslundia opposite 4/33 12.1% Yellow Barked Acacia Acacia xanthophloea 9/33 27.2% Durang N/A 19/33 57.5% Hhangali (Sodum apple) N/A 4/33 12.1% Washawasha N/A 1/33 3.0% Garmo N/A 12/33 36.3% DumeMfufaru Croton microstachys 4/33 12.1% Mori Scolopia spp. 1/33 3.0% Matsafi N/A 2/33 6.0% Kiloviti (Baryomodi) Acacia nilotica 2/33 6.0% Mgunga Acacia spp. 1/33 3.0% Ankwi Vernonia exsertiflora 2/33 6.0% Maslaramo Vangaena madagascaneinsis 25/33 75.7% Minighiti Euclea spp. 14/33 42.4% Sandal wood Osyris lanceolata 1/33 3.0% Msokoni N/A 12/33 36.3% Mgunga Moto Acacia mellyere 3/33 9.0% Use of modern medicine in the Endabash region

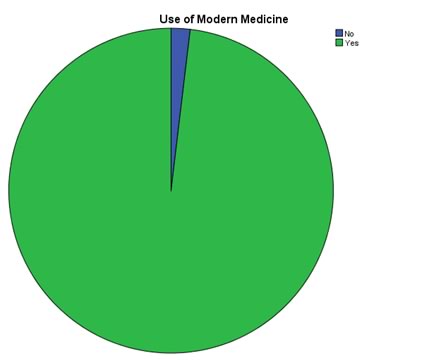

Mentioned previously in this study, only 30.2 percent of the informants interviewed use ethno-medicinal plants for traditional medicine. Figure 5 demonstrates the use of modern medicine amongst the Iraqw in the Endabash region. Out of the 106 informants interviewed, 98.1 percent use modern medicine, while 1.9 percent do not use modern medicine.

Figure 5. Use of modern medicine in the Buger region1.9%

No98.1% YesConservational implications and concerns

Although the majority of the informants do not use ethno-medicinal plants, there still is a conservation concern. Of the informants who said "yes" to the use of ethno-medicinal plants, 34 percent of the people collect the plants from their yards or areas close to their homes. Fifty-five percent claimed that they collect these plants from the community forest. Ten percent of the informants visit the witch doctor or plant herbalist for plant-based medicine. One percent of the informants claimed they grow the plants used for medicine in their yards.

Discussion

Ethno-medicine

The use of traditional medicine is often widespread and deeply rooted in many communities in East Africa (Sindiga et al., 1995). Even today, many indigenous groups such as the people in Southeastern Ethiopia use traditional medicine as their primary medical care. This culturally based healthcare system is often learned orally and is passed down from generation to generation. In most indigenous populations, traditional medicine is deeply rooted in the history, culture, environment, and language (Lulekal et al., 2008). The main objective of the study was to identify the commonly used plant species utilized to treat human diseases. However amongst the Iraqw in the Buger region, the majority did not use traditional medicine (69.8% said "no") and the majority actually relied on modern medicine (98.1%). This suggests that local traditions are no longer the only source of medicine. A nurse who worked at a local dispensary mentioned that the majority of her patients use a combination of traditional medicine as well as modern medicine. However the majority of these patients do not report their use of traditional medicine. Concurrent to her statements, the focus group discussion confirmed that the majority of the inhabitants of the Buger region use a combination of modern and traditional medicine though many of them do not report the use of traditional medicine. In this study, informants also reported that many of the same plant species that are used for medicine are also used for other reasons such as firewood, construction materials, food, and honey collection. Although the majority of the informants did not report their use of traditional medicine, the study still confirmed the reliance on the community forest as well as the versatility of many of the plant species. The data collection of 32 plant species for the use of traditional medicine suggested that, despite the reported percentage of use of ethno-medicine was only 30.2 percent, plant medicine is still prevalent and available.

In this study, several parts of the plant species were used to treat different diseases; bark (37.5%) and leaves (28.1%) were the most commonly used plant parts. Concurrent to these results, Yineger et al. (2008) reported that in the study conducted in Southwestern Ethiopia, the most used parts of the plant species for medicine were the leaves and the bark.

The interviews revealed that the most common disease in the Buger region was Malaria, followed by the common cold. During the interview process, a nurse mentioned that the common illnesses in the area are often associated with water. She said that during the rainy seasons, water runoff from the forest into lower villages is usually warm enough to become a breeding area for mosquitos. Similar to the current study, a study conducted in Kenya amongst the Maasai reported that the majority of the plant species were used to treat Malaria because it was the most common disease in the area. The frequency of Malaria as the most common disease was similar to the current study (Kiringe, 2006).

In this study, several factors were tested with the use of ethno-medicine to show any positive correlations. The factors studied were gender, age class structures, and education level. A chi-square test was conducted in order to determine any correlations. Results showed that the use of ethno-medicine did not depend upon age class structures or gender; however, the use of ethno-medicine depends upon education level. The indigenous medicinal plant use is independent of gender, suggesting that knowledge of plant use is not specific to gender. This implies that traditional plant use for medicine is universal and is utilized by both males and females. Because traditional plant knowledge is orally taught (Cotton, 1996), there is no relationship between the use of ethno-medicine and gender because plant knowledge is passed down to all in the village. This suggests that use of ethno-medicinal plants was inherited knowledge from family members regardless of the gender. Results also showed that indigenous medicinal plant use is independent of age, suggesting no relationship between age class structures and use of ethno-medicine. Thus use of ethno-medicine was inherited knowledge from family members regardless of age. On the contrary, a study conducted in Southwestern Ethiopia suggested that there was a relationship between use of ethno-medicine and age. They found that indigenous medicinal plant use was dependent upon age; the older populations relied on plant medicine (Yineger et al., 2008). The lack of dependency on use of ethno-medicine and age in the Buger region suggests that, amongst the age classes, the interest of using ethno-medicinal plants is universal and distributed evenly. It also shows that community does not suffer from the loss of ethno-medicinal knowledge. Lastly, results showed that indigenous medicinal plant use is dependent upon education level. The results showed that amongst those who use of ethno-medicinal plants, the highest education level achieved was the primary level (75%). This suggests that possibly with less education, there is greater chance of relying on ethno-medicinal plants due to socio-economic factors and to having a better understanding of traditional medicine. Amongst those who use of ethno-medicinal plants, only 10 percent had a secondary education.

Lastly, aside from data collected from interviews, information was collected on the plant species used for medicine. Many of the plants surveyed in the community forest were also found in the local yards of the informants. Such plant species include Maslaramo (Vangaena madagascaneinsis) and Durang, which are used to treat stomach illnesses and malaria. This suggests the versatility of plant species which are able to be grown in the yards as well as the community forest.

Threats to medicinal plants and conservation practices

According to the focus group discussions, there are several climatic factors that could potentially threaten medicinal plant survival. Through matrix ranking, decrease in rainfall (drought) and the loss of wetlands were highly ranked as problems related to climate change. This was followed by an increase in temperature and soil infertility (erosion). Similar to the current study, Lulekal et al. (2008) confirmed that the main threats to the survival of medicinal plants in the Mana Angetu district were agricultural expansion, drought, and soil erosion. Another concern that could potentially affect the conservation of medicinal plants is the utilization of the different parts of the plant. Of the plants that were used for ethno-medicine, the most harvested part of the plant was the bark (37.5%) and the roots (25%). A conservation concern is that by harvesting the bark and roots completely, there is less chance of survival for the entire species. It was also reported that the majority of the informants that do use medicinal plants do not cultivate their own plant species. Results show that 55 percent of the informants who use ethno-medicine collect the plants from the community forest. In order to appropriately ensure the survival of the medicinal plant species, it is important to prevent overuse and establish a better system of collecting plants for medicine.

Limitations of the study

Ethno-botanical data were collected through semi-structured interviews. Although the results showed that 69.8 percent did not use ethno-medicines, there are several indicators of biased data. These interviews were conducted by students who are often referred as "Wazungu," foreigners. This notion could have skewed the data significantly. It is common for informants not to be truthful in answering the question: Do you use traditional medicine? Reasons for biased answers include lack of trust between informants and the researcher and concern for laws and regulations. The Marang forest, located near the southern part of the community forest, officially became a protected forest in 2008. Prior to 2008, many people relied on the forest resources for medicine, firewood, construction, food, and other sources. During the focus groups, the community members mentioned that now that the Marang forest is controlled by The Tanzania National Parks (TANAPA), many people have lost their source of food, medicine, firewood, and construction materials. People are allowed to use the community forest for these resources; however it requires a permit and the majority of inhabitants in the Buger region collect resources without a permit. It is understandable that many informants may have simply not told the truth when asked about use of plant species for medicinal purposes. In a study conducted in Katumba, East Africa, researchers faced a similar problem. Because Bushmeat consumption is an illegal activity, researchers noted that they were unable to obtain reliable answers (Martin, Caro, & Mulder, 2012). Concurrent to the Marten et al (2012) study, Mgagwe et al. (2012) conducted a study in Katavi where informants were questioned about Bushmeat consumption. They discovered that due to the illegality of the consumption of Bushmeat, many informants did not truthfully answer whether or not they used Bushmeat. In a current study on the consumption of Bushmeat, out of 81 interviews it was reported that 8.6 percent of the informants had not truthfully answered questions about use of Bushmeat (Stroming, 2013). The limitations of the current study on use of ethno-medicine in the Buger region likely included biased answers due to a lack of trust between the informant and researcher as well as the strict laws and regulations of using resources from the community forest and the Marang National Park. Due to these circumstances, it is possible that many of the informants did not say "yes" to the use of ethno-medicine when in reality they use plants for traditional medicine.

Conclusion

It is important for the community in the Buger region to establish an appropriate system for the use of medicinal plants. Simply taking the needed plants from the community forest or local areas will decrease the chance of survival for many of the medicinal plant species. Although the climate change phenomenon has impacted every living organism on the planet, it is important to ensure the survival of medicinal plant species for future use. Overexploitation will lead to the extinction of many versatile plant species that are not only used for medicine but also for firewood, construction materials, food, or honey collection. Ethno-botanical data were collected in the Buger region, however it important to continue this study to ensure the survival and perseverance of the use of ethno-medicinal plants. The current study has documented a few plant species that are often used for ethno-medicine; however future studies should continue to collect ethno-botanical data and the uses for human diseases the plant medicine treat. In the future it is also important to increase sample size. This will ensure greater data collection and indicate patterns of significance. Also, a larger sample size will give an accurate representation of the Buger region. Future studies should collect strategies to replenish diminishing medicinal plant resources, ensuring viable ways for continuous availability and sustainability of such resources.

Recommendations

If the demand for medicinal plants increases, there will be an urgent need to sustain the plant species used for medicine. In order to avoid a rapid decrease in medicinal plants, it is important to establish a management and sustainable utilization system for medicinal plants. The current study showed that in the Buger region there is no established management system for the use of medicinal plants. Due to the regulations and laws regarding the Marang forest and the community forest, it is important to implement a cultivation system. Many people travel distances to retrieve these plants from the forests. Manual cultivation of the medicinal plants would eliminate overexploitation of the given plant species.

It is also important to identify priority medicinal plants for conservation, especially those that largely impact human livelihoods. After identifying key species, appropriate agronomic techniques should be implemented to ensure cultivation systems to increase the future availability of the plant species.

Lastly, a better relationship between the government and the local villages would ensure the lasting survival of medicinal plants. The majority of the people fear TANAPA and their rules and regulations. It is likely that the majority of the informants in the current study did not answer the questions truthfully in fear of being reported to governmental agencies such as TANAPA. A policy should be enacted that would empower the local people to freely practice traditional medicine in a sustainable way. Further pharmacological studies should be carried out on popularly used medicinal plant species to establish their bioactivity potential for developing future drugs to cure certain human diseases.

Acknowledgements

This study could not have been undertaken without the help and guidance from Professor John Mwamhanga. He supported the EP directed research group every step of the way, always encouraging us to fulfill our goals. I would also like to thank the School for Field Studies for supporting the study. I am very grateful to the community of Buger Village. Without its support and willingness, this study would not have been successful. I would also like to thank Filemon Isaac for being the best translator and guide. His knowledge and skills contributed to the success of this study. I want to thank Nina and Mike, our drivers. Thank you for getting us safely to our destinations. Lastly, I would like to thank the EP directed research group. Each and every one of you have supported and contributed to the success of this study.

References

African Wildlife Foundation (2003) Lake Manyara Watershed Assessment.

Akerele, O., Heywood, V., & Synge, H. (1991) The Conservation of Medicinal Plants. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

Bodeker G. (2002) Medicinal Plants: Towards Sustainability and Security. Green College, Oxford, UK.

Cotton, C.M. (1996) Ethnobotany: Principles and Applications. New York: John Wiley and Sons Ltd.

Fratkin, E. (1996) Traditional medicine and concepts of healing among Samburu pastoralists of Kenya. J. Ethnobio.16, 63-97.

Hamilton, A.C. (2003) Medicinal Plants, conservation and livelihoods. Biodiv. & Conserv. 13, 1477-1517.

International Union for Conservation of Nature, IUCN (2001) Newsletter of the Medicinal Plant Specialist Group of the IUCN Survival Commission. Med. Plant Conserv. 7.

International Union for Conservation of Nature, IUCN (2002) Newsletter of the Medicinal Plant Specialist Group of the IUCN Survival Commission. Med. Plant Conserv. 8.

Kiringe, J.W. (2006) A Survey of Traditional Health Remedies Used by the Maasai of Southern Kaijiado District, Kenya. J. Plants, People & App. Research 4, 61-74.

Kiringe, J.W. & Okello, M.M. (2005) Use and availability of tree and shrub resources on Maasai communal rangelands near Amboseli, Kenya. Africa. J. Range & Forage Sci. 1, 37-46.

Kumar, S. (2002) Methods for Community Participation: A complete Guide for Practitioners. ITDG Publishing: London, 23 – 52

Lelo Francis et al. (1995) PRA Field Handbook for PRA Practitioners: The PRA Programme Egerton University, Njoro-Kenya

Lulekal, E., Kelbessa, E., Bekele, T., & Yineger, H. (2008) An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in Mana Angetu District, southeastern Ethiopia. J. Ethnobio. & ethnomed.4, 1-10.

Martin, A., Caro, T., & Mulder, M.B. (2012) Bushmeat consumption in western Tanzania: A comparative analysis from the same ecosystem. Trop. Conserv. Sci. 5, 352- 364.

Mgawe, P., Mulder, M.B., Caro, T., Martin, A., & Kiffner, C. (2012). Factors affecting bushmeat consumption in the Katavi-Rukwa ecosystem of Tanzania. Trop. Conserv. Sci. 5, 446-462.

Simon, J.E., Koroch, A.R., Acquaye, D., Jefthas, E., Juliani, R., & Govindasamy, R. (2007) Medicinal Crops in Africa. Bot. & Med., 322-331.

Sindiga, I., C. Nyaigotti-Chacha & M.P. Kanunah (1995 )Editors of Traditional Medicine in Africa. East African Educational Publishers Ltd., Nairobi.

Stroming, Ahren (2013) Bushmeat Poaching and consumption in the Tarangire-Manyara Ecosystem, Tanzania. (Still pending study, has not been published yet).

Yineger, H., Yewhalaw, D., & Teketay, D. (2008) Ethnomedicinal plant knowledge and practice of the Oromo ethnic group in southwestern Ethiopia. J. Ethnobio. & ethnomed.4, 1-10.

|