Lighting, Vision, and Aging in Place: The Impact of Living

with Low Vision in Independent Living Facilities

Jordan Sawyer

Migette L. Kaup*

Kansas State University

Keywords: Low vision, low vision disabilities, older adults, independent living facilities, lighting, lighting design, interior design

Abstract

Due to the large influx of older adults choosing to live independently in retirement communities (Hegde & Rhodes, 2010), it is increasingly important that interior designers understand the physical and environmental challenges that these adults face. Visual impairments such as macular degeneration, cataracts, and glaucoma make it difficult for adults with low vision to navigate the built environment (York, 2012). Improved quality of lighting in a space has the ability to help these users perform daily activities and, therefore, remain independent (Weinstein, 2011). Although independent living facilities have become an attractive housing option for many of these adults, several studies have concluded that the lighting levels in such residences are not adequate to meet the needs of low vision users (Bakker, Iofel & Lachs, 2004; Hegde & Rhodes, 2010; Lewis & Torrington, 2013). By analyzing recent case studies as well as conducting quantitative and qualitative research of lighting conditions in a local retirement community, conclusions were drawn as to what types and levels of lighting were common in these facilities and how these lighting schemes affected individuals with low vision. There were two components to the data collection: assessment of light levels through light meter readings and structured interviews with residents. Suggestions were made for current and future improvements of lighting design in independent living facilities based upon findings from the study.

Introduction

Due to the growing number of older adults with low vision living either independently or in independent living facilities (ILFs), it is of increasing importance for designers to understand the barriers that these adults face and to explore options that may help improve the lighting design of the interior environment. Light becomes more essential for older adults as the aging eye diminishes in its ability to focus and adapt to changing light levels (Gordon, 2003; Krusen, 2010; York, 2012). Numerous studies concluded that light levels in ILFs do not meet standards set by the Illuminating Engineering Society of North America, IESNA, (Bakker, Iofel & Lachs, 2004; Hege & Rhodes, 2010; Lewis & Torrington, 2013) and are, therefore, providing unfit living conditions for residents, especially those with low vision disabilities. By analyzing recent case studies as well as conducting quantitative and qualitative research of lighting conditions in a local retirement community, conclusions were drawn as to what types and levels of lighting were common in these facilities and how these lighting schemes affected individuals with low vision.

Review of Literature

In order to fully understand the issues surrounding this topic, only the most relevant information was secured from a variety of sources. The literature used throughout was systematically gathered from the network of databases and library resources offered by Kansas State University. Additionally, more specific information was gathered from scholarly websites. By searching databases focused on interior design, architecture, health, gerontology, and governmental resources, the scope of information was narrowed while still allowing access to many interesting perspectives. Combinations of targeted keywords were used to obtain broad subjects of research, which were then narrowed down through review of the literature. Evaluations of the relevance of each piece of literature were made through a comparison of content versus overall themes of the work and goals of the study.

Specialist Housing for Older Adults

The need for independent living communities has increased (Benedict, 2001; Hegde, & Rhodes, 2010; Lighting and the visual environment, 2013) as the large Baby Boomer generation has continued to age. These communities have adapted to meet the needs of the older adult population with the added benefits of on-site health services, emergency assistance (Consumer tips, 1991), and nearly maintenance free living, making them an attractive option for adults who wish to remain independent. According to Hegde & Rhodes (2010), by the year 2030 many of the approximate 71 million Americans over the age of 65 will opt to live in ILFs. This generation has observed the preceding generation grow old and has watched the evolution of senior living environments transform into a new, person-focused system in which older adults may remain independent longer. Although impaired health and physical disabilities may become barriers to independence, the solution of specialized housing designed around the typical needs of older people may enable these residents to retain their independence (Lewis, & Torrington, 2013).

Although ILFs make it easier for adults to maintain independence, there are still barriers that these elders face, regardless of living situation. Progressive vision loss is a common concern for many older adults. Because more seniors are choosing to live in ILFs, and even more are projected to move into independent living housing in the near future, it is now even more critical that designers consider the potential impact lighting can have upon the aging population's health and quality of life (Lighting and the visual environment, 2013).

The Aging Eye

There are many physical, mental, and sensory changes that take place in the body and mind as individuals age, all of which may create barriers to living independently. The research focus of this study was to determine sensory barriers, specifically visual impairments, and their effect on adults with low vision living independently in retirement communities. Due to the natural process of aging on the eye, it is likely that every individual will experience some form of progressive visual impairment.

According to Weinstein (2011), most adults with good eyesight will begin to experience some visual deterioration around the age of 40. It is at this age that the eye begins to require more light to accurately perceive and act in the visual environment and the eyes begin to experience a diminished ability to focus and adapt to changing light levels (Gordon, 2003; Krusen, 2010; York, 2012). These changes that take place inside the eye reduce the quality of low-light vision and contribute to the need for improved home lighting for everyday tasks (Krusen, 2010). Not surprisingly, people above the age of 60 require three to ten times as much light as those aged 20 or younger (with normal vision) in order to perform the same seeing tasks with equal speed and accuracy (Hegde, & Rhodes, 2010; Weinstein, 2011).

These visual deficiencies may begin to affect older adults' capacity to live independently. Approximately one in eight people over the age of 75 and one in three people over the age of 90 suffer from a visual impairment serious enough to qualify as partially sighted or legally blind (Lewis & Torrington, 2013). Because light levels required by the aging eye are much higher, it is essential that these needs be met in independent living environments. Fortunately these spaces may be designed to help promote ease of use to those with low vision disabilities. In fact, appropriate lighting has the potential to help people of all ages and levels of ability achieve a higher level of independence in performing daily tasks and activities (Weinstein, 2011).

Conscientious lighting design has such an impact on our ability to see and navigate primarily because the eye is contrast sensitive. This means that, although a certain quantity of light is required in order to see, our subjective experience of space is a function of the degree of contrast present in our environment (Gordon, 2003). For older adults, the need for greater amounts of light competes against another key issue that the aging eye faces: glare—the inability to easily adjust to excess luminance in a space.

Glare occurs when light is misdirected or reflected off a surface and is directed toward the eye (Gordon, 2003). This high contrast of direct or reflected light becomes harder to tolerate as older eyes become more sensitive to glare (Lighting for Older Eyes, 2003). By providing senior living environments with high light levels and limited glare, residents will be able to negotiate their living space more comfortably and with confidence (Hegde & Rhodes, 2010). Therefore, designers should carefully articulate increased light levels for older adults in order to provide the adequate amount of light as well as appropriate contrast in the field of view.

Common Age Related Visual Disorders

According to the World Health Organization, there are four levels of visual function: normal vision, moderate visual impairment, severe visual impairment, and blindness. The term "low vision" represents the combined levels of moderate and severe visual impairments (Visual, 2013). These impairments are not limited to older adults and affect all ages. However, the scope of disabilities discussed will focus on common diseases among older adults; cataracts, glaucoma, and macular degeneration, each of which makes lighting needs critical (York, 2012).

Some type of visual impairment affects 10 percent of people aged 65-75 and 20 percent of those aged 75 and older (Evans, Sawyerr, Jessa, Brodrick, & Slater, 2010), and impairment varies from correctable visual problems to more severe loss of visual function. A common visual disease among older adults is macular degeneration, which is a gradual destruction of the macula, the part of the eye that provides sharp, central vision needed for seeing objects clearly (U.S., 2009). Known as Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD), this disease is responsible for low vision in over 40 percent of adults over the age of 75, making it one of the most common low vision disabilities. The effects of this irreversible disease are characterized by a loss of detailed vision such as facial features and small print (Sperazza, 2001).

Cataracts cause the lens of the eye to lose transparency, thus scattering light. As light scattered inside the eye becomes worse over time, distorted visual function occurs (Evans et al., 2010). Due to this light scatter, the individual often experiences hazy vision, decreased ability to perceive contrast, and increased sensitivity to glare (Sperazza, 2001). After the cataract has matured, this progressive opacification may be corrected by lens replacement surgery.

Glaucoma, an increased pressure build up inside the eye causing atrophy of the optic nerve, produces defects in the visual field. This atrophy first affects peripheral vision. Central vision may remain preserved until late stages of the disease, which left untreated can progress to total blindness (Sperazza, 2001).

Visual Loss & Risk of Falls

Although some loss of ability to do everyday activities is an unfortunate reality to many older adults with low vision, a bigger issue is the increased risk of falls and accidents. According to Paul & Yuanlong (2012), more than 30 percent of adults aged 65 and older fall at least once a year, with the United States averaging 1.8 million nonfatal falls. One study that analyzed and determined factors contributing to falls of older adults suggested that the presence of rugs, certain bathmats, and slippery footwear were three common precursors to falling incidents. Through participant interviews, the research revealed that low-level lighting also contributed to many of the falls (Paul & Yuanlong, 2012). Because falls make up the largest percentage of accidents among older adults, it is conceivable that poor vision affects a person's ability to maneuver around obstacles in a low-lit environment, an environment that potentially intensifies the existing visual problem (Paul & Yuanlong, 2012).

Inappropriate lighting is only one factor affecting the way that older adults with low vision navigate through a space. Designers should also carefully articulate the contrast and properties of material selections. For low vision users, changes in level or floor material may become stumbling blocks as the variation may be imperceptible, an issue that is only amplified under low-light conditions. This combination, along with other environmental factors, creates a higher risk of tripping, falling, or other accidents. A report published by the American Occupational Therapy Association suggested that, "changes to the home environment, including lighting, support functional outcomes and prevent falls" (Krusen, 2010, p. 8). Therefore, implementation of appropriate lighting and material selection may decrease injuries and improve the quality of life of older adults with low vision disabilities.

Lighting Standards in ILFs

Like private residential housing ILFs are not strictly regulated, and bare minimum lighting schemes are often implemented to deter costly renovations. Many studies have examined whether specific facilities met the minimum lighting standards and whether the lighting needs of the residents were met (Bakker, Iofel & Lachs, 2004; Hegde & Rhodes, 2010; Lewis & Torrington, 2013). The IESNA organization developed a set of standards for each type of interior application, including standards for "lighting and the visual environment for senior living" (Hegde, & Rhodes, 2010, p. 382). IESNA contributes to and organizes these guidelines that describe ranges of illumination, colors, textures, and glare and their influence on the lighting design of a space. Light requirements depend upon the detail or speed needed for an activity, and the more precision or speed required for a task, the more light is needed. For example, spaces dedicated to relaxation or entertainment can take place in low to moderate light while reading, cooking, and hobbies require higher light levels (Krusen, 2010).

Consequently, recommended lighting levels are substantially higher for adults aged 65 and older (Table 1). Standards dictate that a minimum of eight to ten foot-candles be considered for general light in common living areas, passageways, and conversation spaces, whereas specific task areas such as grooming, reading, kitchen, and hobby areas range from 60 to 200 foot-candles (Blitzer, n.d.). These guidelines are intended to provide an adequate amount of light for the function of the specific space.

Area or Activity

Under Age 25

Age 25-65

Over Age 65

Passageways

2

4

8

Conversations

2.5

5

10

Grooming

15

30

60

Reading/Study

25

50

100

Kitchen Counter

37.5

75

150

Hobbies

50

100

200

Table 1. IESNA recommended light levels for areas & activities by age group (Blitzer, n.d.).Typical lighting in senior living environments has been an issue well researched across occupational fields. The majority of studies in ILFs revealed that lighting levels were far below standards (Bakker, Iofel, & Lachs, 2004; Evans et al., 2010; Hegde, & Rhodes, 2010; Lewis & Torrington, 2013). One researcher even commented, "Given the prevalence of sight loss amongst older people, we would expect extra-care housing schemes to be well designed for people with sight loss, but currently there is little evidence to show that this is the case" (Lewis & Torrington, 2013, p. 345). Therefore, it may be concluded that general lighting standards are being ignored at the expense of the end users of the space. Recalling that the aging eye requires more light and less glare in order to perform tasks (Weinstein, 2001; Lighting for Older Eyes, 2003), the results of these studies are alarming.

These lowly illuminated living environments are unsafe for residents and ineffective in helping them use and navigate the built environment (Hegde & Rhodes, 2010). Adhering to recommended lighting standards is critical in senior housing environments. However, in some situations, even the minimum lighting standards may not be sufficient for senior housing where a majority of residents suffer from low vision disabilities.

Research Study at Meadowlark Hills

In order to explore this issue of age-related visual impairments and common lighting methods in ILFs, a research study was conducted to measure foot-candles in independent living apartments and compare the results against recommended foot-candles by IESNA. Data from recent case studies and the research study of lighting conditions in a local retirement community were compared to IESNA standards. The hypothesis of the study was that light levels at the Meadowlark Hills facility would not meet the minimum IESNA standards. In addition, the author was interested in determining if IESNA standards were too low for functional use by older adults with low vision.

The goal of the study was to gather information about key lighting areas at a specific senior living environment and determine the effect on older adults with low vision. Data were systematically gathered through voluntary participation of older adults with low vision living at Meadowlark Hills, a specialist housing facility. There were two components of the data collection: structured interviews with residents with environmental observation and assessment of light levels in key areas through light meter readings. Efforts were made to understand the residents' perceptions of their light levels through these interviews. After examining the qualitative and quantitative data recorded from these methods, suggestions were made for current and future improvements of lighting design in these facilities.

The process of enrolling volunteers began with communication to Meadowlark Hills, which has a small group of low vision older adults who participate in monthly meetings. This target group was chosen because they could best describe the barriers of living with low vision and the lighting needs in ILFs. An invitation to learn about the study was extended to the low vision group, and informational meetings were arranged. The purpose and methodology of the research were explained to the residents at each of the three sessions, yielding a group of six volunteers to participate in the study.

Characteristics and demographics of the sample:

- All participants were ages 80 and older with the oldest being 101, giving this group a medical classification of "elderly."

- There were four males and two females.

- Each of the six participants lived autonomously in five separate independent living apartments of Meadowlark Hills. Two of the participants were a married couple.

- Two of the apartments were located in the original building whereas the other three apartments were located in the new addition to the building.

- Common low vision diseases were cataracts, glaucoma, and macular degeneration, with the most frequent being the latter.

- Length and severity of the progression of each disease varied.

Qualitative Data Collection

Interviews. At the beginning of each interview, each resident was read the purpose and methods of the study, and each participant signed a consent form (Exhibit I). Audio-recorded individual interviews consisted of questions relating to the subjects' low vision disability and perceptions of light in key areas of the home (Exhibit II). A few overview questions ascertained general information about which low vision disease the participants had and how long they had been living with low vision. The next series of questions was designed to understand how their vision had affected their daily lives and what accommodations they had made to reconcile these deficiencies. Remaining questions were opinion-based and asked about the individuals' perception of the lighting in their apartment as well as what improvements would help them function in their daily routine.

A common characteristic in the interviews was that although timing and progression of the disease varied, persons had routinely visited an ophthalmologist prior to detection of their specific condition. Once diagnosed, preventative measures were taken to remedy any reversible conditions (such as cataract surgery and eye shots for AMD), but inevitably the disease progressed beyond treatment. Macular degeneration was the most common low vision disease among the participants, affecting two thirds of the group. Cataracts and glaucoma were other low vision diseases present among the participants.

Changes in everyday activities were common in the group. Due to vision concerns, participants had stopped driving, lost almost all reading function, and most participated in limited social activities in the confines of the facility. Many of the individuals remarked about how they could no longer enjoy activities that they once loved, such as traveling, site seeing, watching movies, and shopping. Few individuals cooked meals in their apartments, and most would rather take advantage of the food service available at the community dining rooms; grocery shopping had become burdensome, and cooking was too difficult. Some used simple appliances such as microwaves and toasters.

All participants had made lighting modifications to their apartments. Task lighting was the most common type of lighting adjustment. Each living area observed had several types and sizes of lamps. Work surfaces varied from dining and craft tables to desks. Each work area, independent of proximity to windows or ceiling fixtures, required at least one to three lamps depending on the needs of the user (Figure 1). Several residents had requested additional fixtures where light needs could not be met by supplemental task lighting. Examples included the addition of under cabinet lighting in kitchen areas (See Figure 2), a fluorescent trough ceiling fixture in a craft room (Figure 3), and a fluorescent shelf mounted fixture in a laundry room (Figure 4).

Figures 1-4. Examples of task lighting observed in resident apartments.Observations. Individual perception of the adequacy of light levels in each apartment varied. At first when asked, "Do you believe that the lighting in key areas of your home is adequate?," all but one participant answered that they had become accustomed to the light levels. Responses received were along the lines of: "We get along okay." and "I've gotten used to what I have." Then, when asked whether the lighting was adequate without their modifications to the fixtures provided by Meadowlark Hills, all participants replied that the lighting was very inadequate to meet their needs. For example, in response to the first question regarding overall adequacy of light levels one man answered, "I think so." In response to the second question regarding only existing lighting provided by the facility he replied, "The lighting provided by the ceiling fixtures, no [it is not adequate], but with my lamps it's adequate." It was only with the addition of supplemental fixtures and task lighting that these individuals perceived their light levels as sufficient.

Every participant had also implemented other adaptations such as magnifiers for reading, audio books, automated curtains, and textured buttons that helped the individual operate appliances. The final question of the interview asked about additional improvements that might help improve functionality of daily living in that apartment. Each apartment had different lighting schemes, and each resident had a specific lighting need. Examples included change of fixture type (Figure 5), addition of fixtures (Figure 6), change of direction of light (Figure 7), and modification of light intensity (Figure 8). Although these residents had implemented supplemental task lighting and had rated their light levels as adequate, every individual had suggestions to make the apartments more appropriate to meet their specific low vision needs.

Figures 5-8. Examples of individual lighting schemes observed in resident apartments.Environmental observations of the apartments were compared to resident perceptions of light levels in their homes. Throughout the apartments it was observed that each living room had only one ceiling mounted fan light fixture to illuminate the entire living space (Figure 8). During the day, the presence of only one fixture was not generally an issue as natural daylight supplemented the low-lit environment. However, in the evenings this problem became more pronounced, and a correlation between minimal ceiling fixtures and number of additional lamps became apparent.

There was a noticeable difference between the lighting in apartments located in the original building versus apartments located in the new addition. The two original apartments had the same type of wall mounted light fixture in the bedrooms (Figure 5). This fixture was the only built in light source for the space, and therefore the participants living in these apartments required additional task lighting in their bedrooms. These fixtures seemed oddly placed around the living areas instead of the traditional ceiling mounted fixtures (Figure 9).

Kitchens and bathrooms for the apartments were well lit to meet the needs of the participants. Every bathroom included a vanity light fixture (Figure 10) and an extremely bright heat lamp (Figure 11). The participants used these sources based upon the activity taking place in the bathroom. Similarly, the kitchen area consistently had one ceiling mounted fixture, a light above the sink, and under-cabinet lighting (Figure 12). Many participants stated that, without the under-cabinet lighting, they would not be able to easily navigate their kitchen based upon the overhead fixtures.

Figures 9-12. Examples of overhead fixtures observed in resident apartments.Qualitative Data Collection

After quantifying the data from light meter readings, the hypothesis was confirmed: light levels in observed apartments at Meadowlark Hills did not meet minimum IESNA standards. These findings were consistent with similar studies from the literature. It is important to note that light meter readings were taken under existing artificial lighting conditions in order to record accurate results without the adaptation of supplemental lighting.

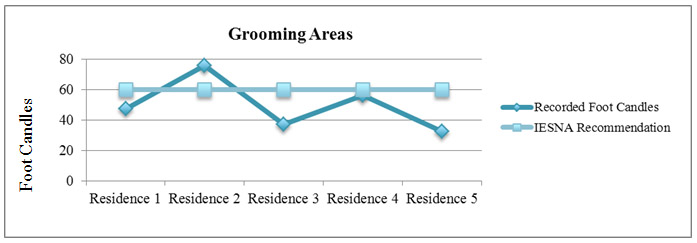

Figure 13. Recorded Foot-Candles in Grooming Areas compared to IESNA RecommendationsData Analysis: Grooming Areas. ESNA recommends that light levels in areas for grooming be at least 60 foot-candles (Table 1). According to the findings (Figure 13), only one of the apartments met the standard. Although the other four apartments fell below the minimum recommendation, the participants' perceptions of lighting in those areas were generally positive.

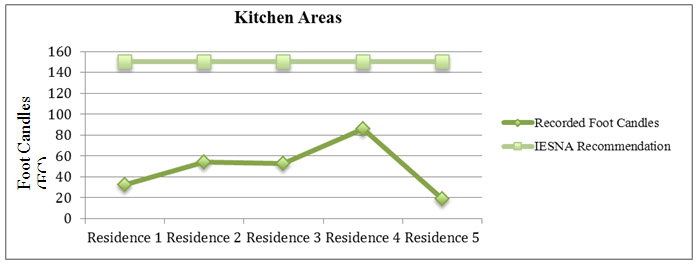

Data Analysis: Kitchen Areas. The next key area observed was the kitchen, where IESNA recommends a minimum of 150 foot-candles be provided to perform tasks. According to the results (Figure 14), every kitchen had average light levels far below that of the standard, yet participants rated their kitchen lighting as adequate.

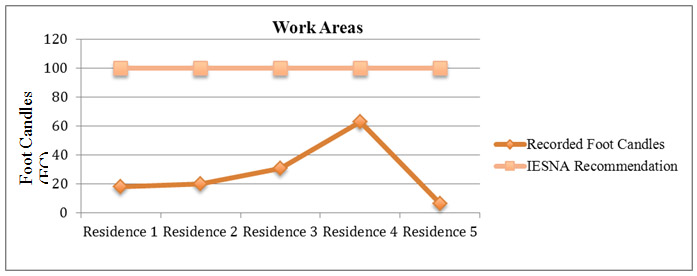

Figure 14. Recorded Foot Candles in Kitchen Areas compared to IESNA RecommendationsData Analysis: Work Areas. The final key area observed was a work surface at which the participant conducted focused tasks. For this application, IESNA recommends at least 100 foot-candles. According to the data (Figure 15), once again recorded light levels fell far below minimum standards. Work areas were consistently modified with additional light sources in order to accommodate the low light levels in these spaces.

Figure 15. Recorded Foot-Candles in Work Areas compared to IESNA RecommendationsLimitations of the Study

Although this study consisted of a small scope and sample size, there were several limitations. A common theme throughout the interviews was that these individuals were used to adapting to the current situation. One man interviewed had stated, "If I want to stay in independent living I've got to adapt to the changing times." This generation of older adults has learned to be content with what they have, and because they are willing to make adjustments to their lives based on environmental factors, this may limit the true perceptions of whether or not light levels were actually adequate in their apartments. Further, when people become accustomed to their environment they rely less on visual cues to navigate the space. Although light levels were lower than standards dictate, the participants had no trouble navigating their apartments because they were familiar with them.

Interestingly, none of the participants had issues with glare in their homes. However, a few commented that they did experience problems with glare from artificial light sources around other areas at Meadowlark Hills and glare from sunlight when outside. Ideally, the study could have included other key areas used by Meadowlark Hills residents rather than only specific independent living apartments. Future studies should be conducted to evaluate the light levels of these other important areas of the space in order to give a more holistic view of the lighting throughout the facility.

Other environmental factors that limited the study included the following:

- The apartments varied in size, layout, and orientation to sun patterns, which affected the amount of natural daylight in the space.

- The apartments in the original building versus the new addition varied in lighting schemes and finishes.

- Timing of interviews and light meter readings were not consistently recorded at the same time of day. Ideally, each session should take place in the evenings when the absence of natural light might make light meter readings more accurate.

Discussion

The results of the study concluded that light levels in observed apartments did not approximate minimum IESNA standards. Although light levels were not adequate, residents' perception of lighting in their apartments was overall positive when supplemental lighting sources were included. It was observed that the areas needing additional light were modified, whereas other spaces were adequate to meet the needs of each low vision participant. Whether or not IESNA standards should be reevaluated for Meadowlark Hills is yet to be determined. To determine this, future studies should be conducted in which an existing apartment is modified to meet the minimum standards and then resident interviews should be recorded as to the satisfaction of light levels before and after the modification.

Based on the results of this study and other studies, the conclusion can be made that ILFs fail to offer even the minimum lighting standards to meet the needs of their residents. One study inferred from the results that the best approach to providing lighting for older adults is to individually investigate the effect of different light levels. "Our results do not support the concept of 'one light level fits all,' but rather indicate that older people with reduced vision should be encouraged to participate in determining the light level that they find is best for them" (Evans et al., 2010, p. 42).

There are some methods that designers should use to help better understand the needs of their older adult clients as well as adjustments that may be implemented to help improve lighting for these older adults. The selection and placement of appropriate light fixture and controls combined with correct selections of light intensity are essential for good lighting design (Weinstein, 2011). Many factors go into the process of deciding what type of light will be most effective in the residence of an adult with low vision. First, it is important to consult with residents as to what their perception of the lighting is and what problems they face. Through interviews and observation, designers should be aware of the inventory and placement of available light fixtures (Krusen, 2010). Once the limitations of the space are determined, the designer may execute a variety of alterations or renovations to help improve light strategies. According to Brawley (n.d.), successful interior lighting environments for aging eyes have conditions defined as (a) providing sufficient light to compensate for the decrease in retinal function, (b) avoiding direct and reflected glare, and (c) providing uniform light levels.

Because each individual requires different types of lighting based on visual needs and personal inclination, control over light fixtures is critical (York, 2012). For example, a universal approach to altering existing lighting design is to incorporate dimmers that allow the resident to adjust light levels based upon the situation and preferences (Lighting for Older Eyes, 2003). Often, task lighting is a more effective, efficient, and economical way to add light to existing space rather than ambient lighting (Krusen, 2010). It is much easier to add fixtures that provide light for specific tasks than to provide overall lighting systems. When incorporating lighting for tasks such as reading, deskwork, or cooking, it is important that the fixture delivers light focused on the activity and not toward the viewer's eye in order to prevent glare (York, 2012). There were several examples of task lighting at the Meadowlark Hills apartments. In the kitchen, under-cabinet fixtures (e.g., Figure 2) were an easy and effective way to add light to food preparation areas. As discussed, many residents also had lamps for tasks in specific areas of their homes.

Conclusion

Loss of visual perception is an obvious limitation to older adults. With limited perception, navigating the built environment becomes a challenge, as many spaces are not designed to accommodate the intricacies of specific types of visual impairments. Persons with normal vision may have no issue casually finding their way around a low-lit environment. However, this situation is completely different for those with a low vision disorder: the field of view may be blurry, dark, or fragmented, making even uncomplicated environments hard to maneuver. The implementation and manipulation of lighting design is an effective means to compensate for aging eyes and diminished abilities (Gordon, 2003; Krusen, 2010; York, 2012).

Because many studies have concluded that light levels in ILFs do not even meet minimum lighting standards (Bakker, Iofel & Lachs, 2004; Hegde & Rhodes, 2010; Lewis & Torrington, 2013), designers should conscientiously select lighting that meets or exceeds IESNA standards to provide the appropriate amount and quality of light for residents. In order to make these alterations, designers should assess residents' lighting needs and implement solutions that are user-focused and provide the safest and most functional senior living environments. These solutions help create living environments that are more comfortable and pleasant to occupy (Brawley & Taylor, 2001), a goal and responsibility of all design professionals of senior housing.

References

Bakker, R. (1999). Elderdesign: Home modifications for enhanced safety and self-care. Care Management Journals, 1(1), 47-54. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.er.lib.k-state.edu/docview/198019610?accountid=11789

Bakker, R., Iofel, Y., & Lachs, M. S. (2004). Lighting levels in the dwellings of homebound older adults. Journal Of Housing For The Elderly, 18(2), 17-27. Retrieved from http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1300/J081v18n02_03

Benedict, E. (2001). When baby boomers grow old. The American Prospect, 12(9), 1-6.

Blitzer, W., (n.d.), Light in design – An application guide, IESNA. Retrieved from http://www.iesna.org/PDF/Education/LightInDesign.pdf

Brawley, E. Lighting. Partner in quality care environments. Pioneer Network. p.1-23. Retrieved from http://www.pioneernetwork.net/Data/Documents/BrawleyNoell-WagonerLightingPaper.pdf

Brawley, E., & Taylor, M. (2001). Strategies for upgrading senior care environments. Long Term Care Management, 50(6), 28.

Consumer tips: Retirement communities. (1991, 03). Consumers' Research Magazine, 74, 2. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.er.lib.k-state.edu/docview/197521002?accountid=11789

Evans, B. W., Sawyerr, H. H., Jessa, Z. Z., Brodrick, S. S., & Slater, A. I. (2010). A pilot study of lighting and low vision in older people. Lighting Research & Technology, 42(1), 103-119.

Gordon, G. (2003). Interior lighting for designers (p.3-10). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Hegde, A. L., & Rhodes, R. (2010). Assessment of lighting in independent living facilities and residents' perceptions. Journal Of Applied Gerontology, 29(3), 381-390.

Krusen, N. E. (2010). Home lighting: Understanding what, where, and how much. OT Practice, 15(19), 8-12. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.er.lib.k-state.edu/docview/856042909?accountid=11789

Lewis, A., & Torrington, J. (2013). Extra-care housing for people with sight loss: Lighting and design. Lighting Research & Technology, 45(3), 345-361. doi:10.1177/1477153512450451

Lighting and the visual environment for senior living (ANSI Approved). (2013). Retreived from http://www.ies.org/store/product/lighting-and-the-visual-environment-for-senior-living-1032.cfm

Lighting for Older Eyes. (2003). Nursing Homes: Long Term Care Management, 52(11), 68-70.

Paul, S., & Yuanlong, L. (2012). Inadequate light levels and their effect on falls and daily activities of community dwelling older adults: A review of literature. New Zealand Journal Of Occupational Therapy, 59(2), 39-42.

Sperazza, L. C. (2001). Rehabilitation options for patients with low vision. Rehabilitation Nursing, 26(4), 148-51. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.er.lib.k-state.edu/docview/218270701?accountid=11789

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, (2009). Age-related macular degeneration: What you should know. Nation Eye Institute. 1-30. Retrieved from http://permanent.access.gpo.gov/gpo25258/webAMD.pdf

Visual impairment and blindness. (2013). World Health Organization. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs282/en/

Weinstein, L. (2011). Good lighting helps... everyone! Pn, 65(5), 58-63.

York, J. H. (2012). Lighting for senior living: ALA panelists discuss impact of aging population on lighting business. Home Accents Today, 27(12), 22.

Retrieved from http://bi.galegroup.com.er.lib.k-state.edu/essentials/article/GALE|A318753002/44be7dcb366321ac26acd260e6679bfe?u=ksuExhibit I

Lighting, Vision, and Aging in Place: the Impact of Living with Low Vision

Consent formProject Description:

This project sets out to assess light conditions of individual residences for people who experience low vision. Information will be collected through a process of structured interview questions and light meter measurements in key target areas of the home including: kitchen, bathroom, dining room and other important work areas (such as a desk surface). Photographs of these surfaces will also be recorded to accurately document meter readings to specific locations.

You have volunteered to participate in this study, which will include an environmental assessment of the light levels in your home and a short structured interview regarding issues that affect your everyday life due to low vision. Interviews will be audio recorded for further review and reference, and will be kept confidential. This process should take no longer than one hour and will contribute to research investigation about design related topics that may benefit from knowledge gained in this study.Risks and Benefits:

The information collected may be kept confidential if you desire. Please indicate your preference on the form below. The data collected will be used in future publications that are intended to be submitted to a research journal. Your participation is voluntary, and there are no risks to you personally by agreeing or not agreeing to participate in this project. You are free to withdraw participation at any time without penalty. There are no direct benefits to you for participating.

If you have questions about participating in this project, including your rights as a participant, please contact Rick Scheidt, Chair, Committee of Research involving Human Subjects, 203 Fairchild Hall, Kansas State University, University Research Compliance Office (URCO) at 532-3224, or [email protected].If you agree to participate in the interview, please sign below.

I, _________________________________, have read the above project description, and agree to participate in this study.

______ I prefer to have my name withheld from any records regarding this project.

OR

______ I grant permission to have my name printed in any records regarding this project.Date ______________________________

Exhibit II

Lighting, Vision, and Aging in Place: the Impact of Living with Low Vision

Structured interview questions:

- What type of low vision disorder do you have?

- How did you first discover that your vision was compromised?

- What changes have you experienced in your every day activities due to the disorder?

- Do you believe that the lighting in key areas of your home is adequate? Why or why not?

- Do you experience problems with glare off of surfaces in your home?

- What aspects of your apartment have you modified in order to accommodate your low vision?

- In your opinion, what improvements to your living areas would help you more efficiently live and function in your daily routine?

|