The Effectiveness of Model-Lead-Test and a Break Card with Hand-over-Hand Tracing on the Handwriting for a High School Student with Autism

Emalia C. Steele,

Mika S. Aoyama,

Jennifer M. Neyman*,

T. F. McLaughlin*

Gonzaga University

and

Kim Hatch*

Spokane Public Schools

Keywords: autism (ASD), model-lead-test error correction, handwriting, legibility, lower case letters

Abstract

The purpose of the present study was to evaluate the effectiveness of a Model-Lead-Test (MLT) procedure on letter size and legibility for lowercase alphabetical letters. The participant was a 15-year-old male high school student. A multiple baseline design across three sets of letters was employed to evaluate the efficacy of the intervention. A break card procedure and hand-over-hand prompting was added five sessions after the first intervention to improve his writing. These changes produced large gains in his handwriting. When this procedure was added to the next set of letters, increases in performance took place. However, for three sessions for this set of letters, the participant was unable to improve his handwriting performance. A multiple baseline design across three sets of letters to the midline, above the midline, and below the midline was employed to evaluate the efficacy of the intervention. The participant's ability to demonstrate appropriate size and form of lowercase alphabetical letters was found. Unfortunately, intervention on Set 3 did not occur. The procedures were easy to implement and employ in the classroom setting.

Introduction

Handwriting is a skill that is typically developed in the early elementary years when a child has developed age appropriate fine and gross motor skills (Graham, 1999). Therefore handwriting is traditionally taught in the kindergarten and primary grade levels. Handwriting is an important skill to learn as poor handwriting can influence other academic areas (Carlson, McLaughlin, Derby, & Blecher, 2008; Cosby, McLaughlin, Derby, & Huewe, 2009). Children with disabilities may struggle to develop handwriting skills due to developmental problems impacting fine and gross motor skills. Children with ASD spectrum disorder (ASD) frequently have problems with fine motor skills impacting handwriting legibility (Ambrumer, Zivani, & Pennington, 2012; Kushki, Chau, & Anagnostou, 2011; Van Drempt, McCluskeky, & Lannin, 2011). Research has also suggested that children with ASD may experience notable difficulties and delays in motor resonance (McCleery, Elliott, Sampanis, & Stefanidou, 2013). In addition, about 30 percent of children with ASD have moderate to severe loss of muscle tone, which can also inhibit their gross and fine motor skills (McCleery et al., 2013). Other barriers in developing legible handwriting skills include sensory difficulties. When children with ASD are asked to respond to sensory stimuli, it could cause stress and anxiety as they attempt to interpret what others are saying to them. When information is presented at a rapid pace this can produce an overload of information and cause the child to shut down. This is particularly true of auditory information, as it has been found that children with ASD are often better visual learners. Some research has suggested keyboarding is easier for children with poor motor skills. However, Blank (2002) believed that writing, whether in the form of handwriting or keyboarding, demands motor skills. For most individuals with ASD, fine motor skills are often their weakest areas. Blank indicated that, "left to their own devices, when they are asked to handwrite, the letters often are simply big shapeless masses sprawled across the page. Left to their own devices, when children are asked to keyboard, they engage in seemingly random movements, hitting keys in meaningless fashion that ends up with little more than jamming the keyboard" (Blank, 2010). Ambrumer et al. (2012) evaluated the effectiveness of keyboarding with 22 students with ASD. None of their statistical comparisons indicated that keyboarding was superior to handwriting on writing assignments. However, their keyboarding was viewed as more legible, and their participants' parents and teachers felt the participants were more motivated with keyboarding.

According to Feder and Majnemer (2007), the failure to obtain handwriting competency within the school-age years has negative effects on both academic success and self-esteem. Handwriting is not only an important skill within an individual's academic years but is also an important lifelong skill in the real world. If an individual is unable to legibly and appropriately size letters as well as form them, writing checks and signing one's name may be difficult for others to read (Graham, 1999). Because handwriting requires a lot of dexterity and fine motor control in order to be legible, an individual needs to be taught and corrected on how to correctly use and manipulate his or her hands to hold a writing utensil.

Fine motor control, bilateral and visual-motor integration, motor planning, in-hand manipulation, and sensory awareness of the fingers are some of the skills that are necessary in order to achieve legible handwriting (Feder & Majnemer, 2007). Deficits in more than one of these factors may be present in a child with ASD. As a result, it is recognized that multiple factors may inhibit an individual's capacity to appropriately develop handwriting skills. For instance, poor handwriting may be related to intrinsic as well extrinsic factors (Feder & Majnemer, 2007). An individual may not have the actual handwriting capabilities, such as motor control, and different fine motor skills are needed to perform better formation, letter size, and letter legibility, all of which are necessary in order to achieve successful handwriting. Graham (1999) agreed that poor handwriting can be a barrier in children with learning disabilities. Because of the lack of fine motor skills and visualization deficits, this may be especially difficult for a student with ASD (Carlson et al., 2009). Handwriting may be one of the biggest obstacles that children with ASD must overcome in order to be fully integrated into a general education classroom.

Even though computer-based writing within the education system has become important because of the technological world that society has created, it is still very important that a child has the ability to correctly form and size letters. Even in a professional work setting handwriting is still an essential and crucial part of daily life. Handwriting is a basic and fundamental way of communicating with the people in one's surrounding, and when handwriting is illegible communication cannot occur. There is evidence that schools were not teaching and encouraging proper handwriting because about 10-30 percent of school-aged children have handwriting difficulties and these difficulties were not fixed without intervention (Feder & Majnemner, 2007). However, it has been shown that handwriting interventions have been successful and involve a great deal of both classroom observation as well as teacher consultation.

Even though developing a successful intervention for handwriting for students can be difficult, there are successful interventions and successful methods. According to Cosby et al., (2009), using tracing and modeling derived from the Handwriting Without Tears®program as well as using worksheets from the intervention program. Cosby et al. developed the Handwriting Without Tears® worksheets and a visual model to increase a preschool student's ability to write letters. In this study, a preschool aged student was given a Handwriting Without Tears®worksheet for a specified letter. The instructor used the verbal prompt "We're going to write the letter_____" and continued using verbal prompts to guide the child in appropriately writing the given letter. For example, for the letter L, the instructor would say, "start at the top, big line down, little line across." This study was successful as the participant was able to correctly write all the letters in her name at the end of the intervention. McBride, Pelto, McLaughlin, Barretto, Robison, and Mortenson (2009) were also able to teach preschool students with severe disabilities to write more legibly employing Handwriting Without Tears® procedures. Recently, Griffiths, McLaughlin, Donica, Neyman, and Robison, (2013) were able to improve the handwriting of two preschool students with developmental delays employing this same program. Delegato, McLaughlin, Derby, and Schuster (2013) had similar success with five preschool students with developmental delays. Batchelder, McLaughlin, Weber, Derby, and Gow (2009) taught a middle school student with ASD to legibly write his name. They employed hand-over-hand prompting was well as dot-to-dot tracing with a middle school student with ASD.

The overall purpose of this study was to evaluate the effects of a MLT procedure on the correct size and formation of lowercase letters with a 15-year-old male with ASD in a self-contained classroom. Another purpose was to extend and replicate the use of MLT with a high school student. Finally, we wanted to determine if we could improve the handwriting performance of a student older than the middle school student taught by Batchelder et al., (2009).

Method

Participant and Setting

The participant (referred to as "Mark") was a 15-year-old ninth-grade boy diagnosed with autism (ASD) who attended a local public high school. Mark's areas of difficulty included writing and exhibiting quiet, calm behaviors during and outside of class. The participant lived with his grandmother who was very involved in his academic endeavors and provided support for him. When writing, Mark lacked the ability to write his letters in the correct size and format. His skill level of writing was equivalent to a kindergarten student. The researchers' cooperating teacher suggested they work with Mark because of his excellent demeanor, desire to please, motivation to learn, and the need he had in learning to write appropriately. Mark was also noted as being vulnerable because he had often been moved between different homes and schools; however, he was finally at a school where he would remain during the rest of his high school education.

The study took place in a self-contained special education classroom in a large, urban Pacific Northwest school. There were 16 students in the class throughout the day working on individual assignments or working together as a group to complete a task. The researchers conducted the study during 5th period, from 12:35-1:30 p.m. every Wednesday and Friday and during 2nd period, from 9:30-11:00 a.m. every Tuesday and Thursday. Typically, on Wednesdays and Fridays there would be at most two other students in the classroom during the intervention. On Tuesday and Thursday, there were 10 students in the class. The intervention was conducted at the participant's desk or at a table in the back of the classroom. Each session lasted between 15-20 minutes with 1-2 minute breaks every 5-10 minutes to allow the participant to get a drink of water. The study was conducted by the researchers while completing the course in classroom management as part of the major in special education at a local private university.

Materials

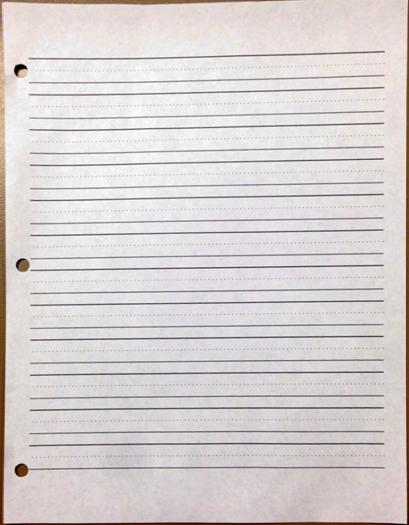

The materials used in this study included wide ruled, 8.7 mm, notebook paper with a midline (dotted line across the center), wide ruled, 8.7 mm, notebook paper without the midline, handwriting worksheets, pencils, and data sheets. For intervention, handwriting worksheets were used from the "Donna Young's Homeschool Resources and Printables" online (Young, 2013) database in addition to tracing worksheets that were made for the intervention.

Dependent Variable

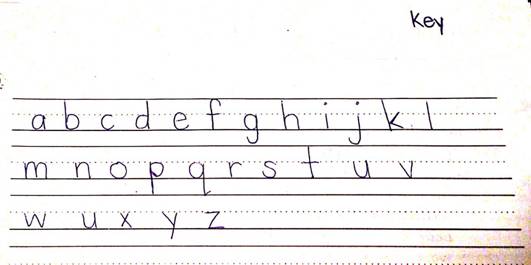

The target behavior in this study was the writing of lower case alphabetic letters with correct letter size, form, and letter formation. Correct size was defined as a) the letter did not exceed the line space (wide ruled) paper provided, b) each letter's height had a consistent relationship with one another, and c) equal or similar distance between letters. Correct form was defined as a) legibility of the letter and b) letter formation had to match the handwritten sample (see Appendix E). In order to get credit for a correct response the letter written had to follow the form, meaning the direction and order of line movement. For Set 1, the letters could not go above the midline. For Set 2, the letters could not go past the top line and could not go below the bottom line. The letters for Set 2 needed to have a vertical line that stretches from the top of the line to the bottom of the line without going past the bottom line and past the top line. For Set 3, the letters could not exceed past the midline and had to go below the bottom line. In addition to the middle part of the letters, the part of the letter that is not a vertical line, for Set 2 and Set 3 also had to be within the midline to receive credit. All parts of the letter had to be correct to be counted as a correct response.

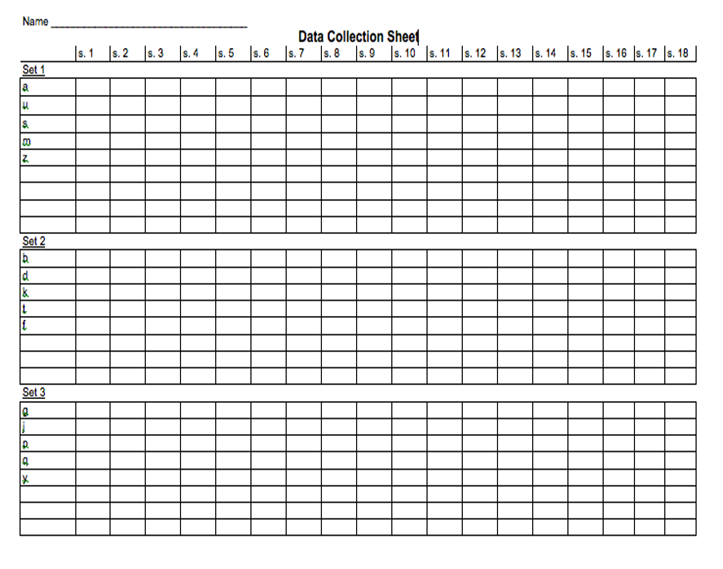

Data Collection and Inter-Observer Reliability

For each session the researchers said letter names of the alphabet in random order for the participant to write. The researchers reviewed the participant's response and compared his response to the key. The participant would then receive a plus for a correct response and a minus for an incorrect response. The pluses and minuses were then marked in the data sheet (See Appendix A). Then the pluses were added together and the participant could receive anywhere from 0 to 5 on each set. The correct responses for each session were recorded on the graph.

Inter-observer reliability or agreement was conducted once during baseline and fifteen out of thirty-one times during the MLT intervention. The researchers randomly designated someone as the primary data collector and secondary data collector for the entire duration of the study. The primary data collector examined Mark's written alphabetic response to see if each letter within the set met the criteria for a correct response. Scoring occurred immediately following the session after Mark was excused. No markings or scorings were written on Mark's worksheets. After the researcher concluded the session, the secondary observer was given Mark's responses to perform reliability. The percent of inter-observer agreement was determined by dividing the smaller number of correct responses from one observer by the larger number of correct responses from the second observer and then multiplying by 100. The average inter-observer agreement was 91 percent and the range was 87-100 percent.

Experimental Design and Conditions

A multiple baseline design (Kazdin, 2011; McLaughlin, 1983) across three sets of alphabetic letters was used to evaluate the effects of a MLT system on correctly writing alphabetic letters from a fifteen-year-old boy. Two days of baseline were taken with Set 1 letters, twenty-two days of baseline were taken for Set 2 letters, and thirty-one days of baseline were taken for Set 3 letters. The first two authors began intervention with a MLT but, after seven days of intervention for Set 1, a phase change occurred in which work-break cards, Hand-Over-Hand, and tracing worksheets were added. Therefore, after session 9, intervention for Set 1 included all strategies listed above. Set 2 had nine days of the intervention using all the strategies listed above, and Set 3 had not yet met criteria for intervention. The decision for intervention of Set 1 was shown after there were zero incorrect responses for two consecutive sessions. For Set 2 and 3, the previous intervened Set had to show five correct responses for two consecutive sessions.

Baseline. During baseline, a researcher gave Mark half-inch handwriting paper with a dotted line in between two solid black lines. The participant was told to write all the lowercase letters of the alphabet, when dictated to him in random order, in lower case. The researcher asked the participant if the letters should be upper case or lower case to ensure that Mark understood the direction. After completion of writing the alphabet, he was then given a panagram, (a sentence that uses all the letters of the alphabet). We created a list of five sentences and had him write one of the five panagrams in each session. During the writing of the panagrams, the participant was given corrections for any misspelled words. He was redirected with verbal prompts if he was off task and specific praise was given when Mark was focused on his work. No direct feedback on Mark's performance was given. Specific and general praise were given for effort in responding, overall cooperation, and appropriate behavior.

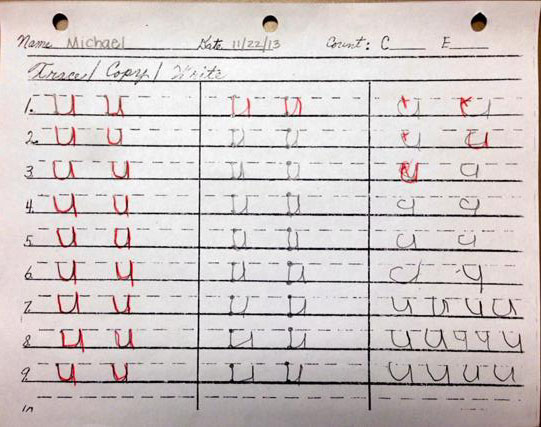

Model-lead-test on handwriting skills. A MLT procedure was used in combination with contingent rewards (computer time) to help our participant master correct form and size of lower case letters. One letter was presented each session. The researcher modeled the correct process for writing that letter and pairing it with verbal "song" prompts (e.g., for the letter z, the researchers said, "across, fall down, across"). The researchers then asked Mark to say the song with them while writing the letter. Finally, Mark was tested to see if he could perform both tasks (singing and writing) independently. Verbal prompts were given when Mark stopped singing the song while writing or when he was not using the correct form. If errors were consistently being made (e.g., using incorrect form), the researchers recalled the song while modeling it in order to refocus the participant on the correct way to write the letter. Depending on the number of data sessions taken on a given day determined how many times Mark was required to write the letters, it ranged from one to three.

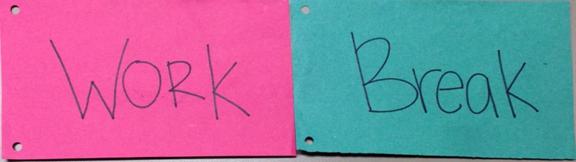

After seven sessions of intervention on Set 1, the researchers reevaluated the effectiveness of the sole use of a model-lead-test procedure. It was determined that an additional intervention strategy was necessary. Because the researchers noticed an increase in Mark's inappropriate behaviors, the researchers introduced a work-break card. The researchers also started using hand-over-hand tracing in addition to more verbal prompting to ensure that Mark was using the correct form for his letters. At the beginning of a session, the researchers used MLT to introduce a new letter to the participant. This was paired with verbal prompting and hand-over-hand. On the participant's desk, there was a work card on the right and a break card on the left. The researchers introduced these cards because the participant was unable to express if he needed a break. If the participant exhibited inappropriate work behavior, the first two authors prompted him by asking if he needed a break. Following the introduction of the new letter, the participant would be given a tracing worksheet in which he would trace the correct targeted letter. The tracing was faded throughout the worksheet and eventually at the completion of the worksheet the participant was writing the letters independently of the model. However, the MLT remained in effect.

Results

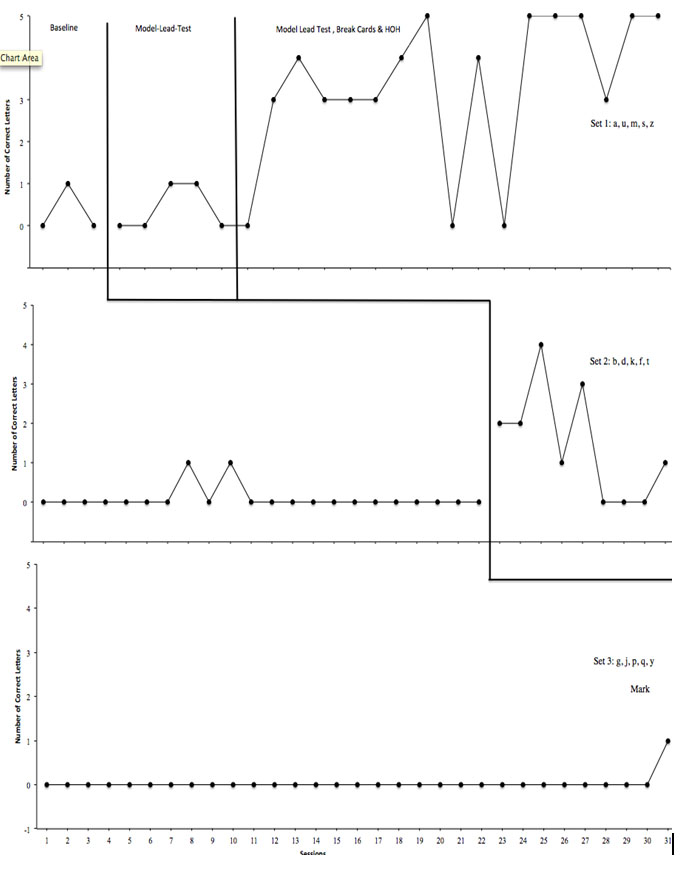

The results of this study are displayed in Figure 1. For Set 1, the mean number of correct responses during baseline was 0. Then, the mean number of correct responses during the MLT intervention increased to 1 (range was 0-3). Once the work-break cards and Hand-Over-Hand was introduced after session 9, the mean average of correct responses was 2.4 (range was 0-5 for Set 1). The mean number of correct responses during Set 2 baseline was 0.1 with a range of 0-1. For Set 2, the mean number of correct responses during the MLT, break-card, and Hand-Over-Hand intervention increased to 2.2 (range was 1-4). The mean number of correct responses during Set 3 baseline was 0. Intervention did not occur on Set 3, therefore there were no results.

Figure 1. Results of number of correct letters per set across three sets of letters during baseline, MLT, MLT+ Break Card, + HOH Tracing.

Discussion

Although the researchers were only able to intervene on the first two sets, Mark showed an increase in his ability to correctly form and size the letters of the alphabet. This improvement was more evident after the researchers added the work-break cards and Hand-Over-Hand procedure. The use of the hand-over-hand procedure replicated prior research (Batchelder et al., 2009). Prior to the intervention, Mark had no concept of how to appropriately size lowercase letters. Previous to the study, the researchers observed Mark completing worksheets in class and noticed his weakness in letter writing. To confirm their hypothesis, the researchers asked Mark to discriminate between which letters of the alphabet go above the midline, below the midline, and to the midline. Mark's inability to indicate such differences confirmed the researchers' hypothesis.

The researchers began the intervention with a MLT procedure because Mark had not yet mastered the ability to appropriately form and size his lowercase letters. The intervention results on Set 1 did not demonstrate learning of how to size and form letters. Mark was exhibiting significant inappropriate behaviors that included self-stimulating, vocal outbursts, and showed physical and verbal aggression towards the researchers. As a result, the researchers chose to reevaluate the effectiveness of the MLT procedure and decided to add work-break cards for behavior and attentiveness, and hand-over-hand procedure for handwriting. Mark's learning in Set 1 dramatically improved at session 16 after the additions had been implemented for several sessions.

The impact of which component contributed to the outcomes cannot be determined. The researchers chose procedures such as hand-over-hand tracing (Batchelder et al., 2009), a practice used in previous research. The use of a break card was documented in the functional communication literature for person with ASD (Carr & Durand, 1985; Hodgdon, 1995; Iwata, Dorsey, Slifer, Bauman, & Richman, 1994).

The participant was more focused on Wednesdays and Fridays because there were fewer students in the class to create possible disruptions. Occasionally, Mark indicated that he preferred to have the classroom lights off which helped him stay on task.

Specific verbal praise paired with high fives proved to be the most effective form of reinforcement. The improvement in Mark's performance with verbal praise and physical contact demonstrated the importance of pairing the two together. This allowed Mark to really focus when he responded correctly or exhibited appropriate behaviors.

There are several strengths in the present case report. The first strength of this study included the constant evaluation of the effectiveness of the intervention by the researchers. Time was taken to ensure that the intervention best illustrated Mark's current level of performance. The researchers also made an effort to collect data and kept a daily schedule. Another strength was the use of multiple intervention strategies. Employing single case research designs allows one to add procedures and continue to assess their effects (Kazdin, 2011). Adding the work-break card and hand-over-hand tracing to the MLT procedure improved our participant's handwriting. The researchers successfully determined the best combination of strategies that maximized Mark's written performance. The researchers interacted with Mark in a variety of settings every day of the school week and this allowed for positive rapport with the participant. Over time, the positive relationship that was developed between the researchers and Mark helped facilitate willingness and cooperation to complete tasks.

The limitations of the study included the time needed to fully teach Mark how to appropriately form and size his letters. Because Mark worked off campus every Monday, the researchers were unable to intervene on Mondays. If data and intervention could have occurred on Mondays, the researchers might have been able to note more overall improvement and potentially conduct intervention on Set 3. Because so many different procedures were implemented in this study, the individual contribution of each cannot be determined. This should provide a fruitful area for future research.

The researchers recommend for future study that data and the procedure be implemented twice a day, once in the morning and once each afternoon. Each session should last approximately 20-30 minutes. Continuation of the work-break cards and hand-over-hand procedures should supplement the use of MLT. It is also recommended that a quiet, distraction-free environment with the lights off be established for each session.

Author Notes

This research was completed in fulfillment for the requirements of Classroom Management in the Department of Special Education at Gonzaga University. Portions of these data were presented at the Spokane Intercollegiate Research Conference, April 2014.

References

Ambrumer, J., Zivani, J., & Pennington, A., (2012). The introduction of keyboarding to children with autism spectrum disorders with handwriting difficulties: A help or a hindrance? Australasian Journal of Special Education, 6, 32-61.

Batchelder, A., McLaughlin, T. F., Weber, K. P., Derby, K. P., & Gow, T. (2009). The effects of hand-over-hand and a dot-to-dot tracing procedure on teaching an autistic student to write his name. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 21, 131-138.

Blank, M. (2002). Classroom discourse: A key to literacy. In K. G. Butler, & E. R. Silliman (Eds.), Speaking, reading and writing in children with language learning disabilities: New paradigms in research and practice (pp. 151-173). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Carlson, B., McLaughlin, T. F., Derby, K. M., & Blecher, J. (2009). Teaching children with autism and developmental delays to write. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 17, 225-238. Retrieved from http://www.investigacion-psicopedagogica.org/revista/new/english/anteriores.php

Carr, E. G., & Durand, V. M. (1985a). Reducing behavior problems through functional communication training. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 18, 111-126.

Cosby, E., McLaughlin, T. F., Derby, K. M., & Huewe, P. (2009). Using tracing and modeling with a handwriting without tears® worksheet to increase handwriting legibility for a preschool student with autism. Open Social Science Journal, 2, 67-69. Retrieved from: http://www.benthamscience.com/open/tosscij/

Delegato, C., McLaughlin, T. F., Derby, K. M., & Schuster, L. (2013). The effects of using handwriting without tears® and a handwriting racetrack to teach five preschool students with disabilities pre-handwriting and handwriting. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention, 6, 255-268.

Feder, K. P., & Majnemer, A. (2007). Handwriting development, competency, and intervention. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 49, 312–317.

Graham, S. (1999). Handwriting and spelling instruction for students with learning disabilities: A review. Learning Disability Quarterly, 22, 78-98.

Griffiths, J., McLaughlin, T. F., Donica, D., Neyman, J., & Robison, M. (2013). The differential effects of the use of handwriting without tears ® modified gray block paper to teach two preschool students with developmental delays capital letter writing skills. i-manager's Journal on Educational Psychology, 7(1), 13-22.

Hodgdon, L. (1995). Visual strategies for improving communication practical supports for school and home. Troy, NY: Quirk Roberts Publishing.

Iwata, B. A., Dorsey, M. F., Slifer, K. J., Bauman, K. E., & Richman, G. S. (1994). Toward a functional analysis of self-injury. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 27, 197-209.

Kazdin, A. E., (2011). Single case research designs: Methods for clinical and applied settings (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

Kushki, A., Chau, T., & Anagnostou, E. (2011). Handwriting difficulties in children with autism spectrum disorders: A scoping review. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41, 1706-1716.

McBride, M., Pelto, M., T.F. McLaughlin, T. F., Barretto, A., Robison, M., & Mortenson, S. (2009). The effects of using Handwriting without Tears® procedures and worksheets to teach two preschool students with severe disabilities to write their first names. The Open Education Journal, 2, 21-24. Retrieved from: http://www.benthamscience.com/open/toeduj/index.htm

McCleery, J. P., Elliott, N. A., Sampanis, D. S., & Stefanidou, C. A. (2013). Motor development and motor resonance difficulties in autism: relevance to early intervention for language and communication skills. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience, 7. Retrieved from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3634796/?report=reader#__ffn_sectitle

McLaughlin, T. F. (1983). An examination and evaluation of single subject designs used in behavior analysis research in school settings. Educational Research Quarterly, 7, 35-42.

Van Drempt, N., McCluskey, A. & Lannin, N. A. (2011). A review of factors that influence adult handwriting performance. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 58, 321–328.

Young, D., (2013). Handwriting Worksheets, Paper, Tips, & Fonts. Donna Young's Homeschool Resources and Printables. Retrieved from http://www.donnayoung.org.

Appendix A: Data Collection Sheet.

Appendix B: Tracing Worksheet.

Appendix C: Handwriting Template, received from Donna Young Website.

Appendix D: Work-Break Cards Sample

Appendix E: Key or template used for scoring participant's written responses

|