Nutritional Profiling Systems: Can They Be Implemented in Subsidiary Food

Pantries for

Reducing Nutrient Deficiencies Among the Elderly?

Rebecca L. Walker

Olivet Nazarene University

Abstract

Learning Outcomes: Identify the nutritional adequacy of food pantry boxes and recognize the potential of nutrition profiling to reduce nutrient deficiencies in the elderly.

Background: The elderly food pantry client (> 60 years old) has increased risk for nutrient-related deficiencies due to a reduced intake of macronutrients, Iron, Calcium, and Vitamins A and C.

Methods: This mixed method design examined the presence of nutritional profiling systems in the United States Department of Agriculture's Commodity Supplemental Food Program (CSFP), two regional food banks, and three subsidiary food pantries through six interviews and a 10-question survey with each facility director. The pantries were selected for their designation as a full or partially client-choice food pantry. Additionally, a nutritional analysis of a sample of 10 boxes from each pantry and 1 box from the CSFP (total n=31) was completed using MyPlate Supertracker.

Results: Two themes emerged from the data: first, nutritional profiling was not a system in use and, second, there is a desire to implement a system if the regional food banks create it. The nutritional analysis sample provided an average of 102 percent of carbohydrates, 66 percent of protein, 45 percent of fat, 34 percent of Calcium, 131 percent of Iron, 47 percent of Vitamin A, and 34 percent of Vitamin C of the Recommended Dietary Allowance for an elderly male client.

Conclusion: These findings indicate that nutrition profiling is not currently utilized, but pantries are interested in utilizing a system if provided by food banks. Because this study was exploratory, results cannot be generalized without further research.

Introduction

The elderly food pantry client is at higher risk for a nutrient-related disease state than the general population (Kamp, Wellman, & Russell, 2009). These clients are often food insecure and must rely on the Commodity Supplemental Food Program (CSFP) to provide a portion of their nutritional needs. The CSFP is a federal program that distributes shelf stable milk, grains, legumes, fruits, and vegetables monthly to individuals over the age of 60 and to pregnant, breastfeeding, and postpartum women. Although these boxes may help reduce hunger, they do not provide adequate nutrition for an elderly adult. Consequently, many elderly adults turn to their local food pantries to increase their food supply. For many food pantry clients, it is difficult to determine the healthfulness of their foods. They may have insufficient time to read nutritional labels while they are choosing their food items, or they may not have the knowledge to understand the food labels. Many subsidiary food pantries lack a nutrient profiling or ranking system by which clients can determine the healthfulness of their products. A nutrient profiling system is a tool that calculates the nutritional quality of a food product and ranks it as a good, better, or best choice. It is designed to increase the nutritional quality of foods consumed by pantry clients and provide an indicator of progress toward the food bank's nutrition goals. The author of this study predicted the food pantries included desire to implement a nutritional profiling system in order to increase the nutritional quality of their products. Additionally, it is undetermined what nutrients these subsidiary food pantry boxes provide on a consistent basis. As a result, it is unknown what percentage of an elderly participant's nutritional needs are met through the foods that are contained within the pantry boxes.

The purpose of this study was to determine if food banks, food pantries, and the CSFP in the sample have implemented, or are willing to implement, a nutrient profiling system into their organizations. The study sought to answer the following questions: (a) What nutrition profiling systems are currently being utilized in the Commodity Supplemental Food Program?, (b) What is the process by which regional food banks complete nutritional profiling?, (c)Would subsidiary food pantries desire to implement a nutritional profiling system?, and (d) What percentage of an elderly client's daily average requirement of kilocalories, fat, protein, iron, calcium, sodium, Vitamin A, and Vitamin C is provided by local food pantry boxes? It was predicted the CSFP would not have a nutritional profiling system but that the regional food banks would utilize either the Choosing Healthy Options Program (CHOP) or an independently created system. The CHOP was created by the Greater Pittsburgh Community Food Bank and ranks foods as 1 (best), 2 (better), 3 (good), or MC (minimal contribution). In addition, the purpose of the study was to investigate the nutritional content of a sample (n=31) of food pantry boxes in order to educate the food pantries on the nutritional content of their boxes. The predicted hypothesis was that the sample of food boxes would provide 50 percent of one's daily needs in kilocalories and the selected macronutrients (carbohydrates, protein, and fat) but less than 50 percent in the selected micronutrients (Calcium, Iron, Vitamin A, and Vitamin C). In the coming years, the nutrient content of food boxes supplied by food pantries must be evaluated in order to provide a more nutritionally complete component for the nutrient vulnerable population (Kamp, Wellman, & Russell, 2009).

Review of Literature

"When people need food bank food for only a few months of their lifetime, quality is less important than quantity. When it becomes a consistent need, year after year, the issue of food quality must be addressed" (Greater Pittsburgh Community Food Bank, 2011a, para. 6). Food banks, named because they provide food supplies to many agencies and individuals, have become a primary resource for many impoverished individuals in the past 20 years. Since businessman John van Hengle started the first food bank in Phoenix, Arizona in the 1960s, the number of clients has increased to 37 million annually (Feeding America, 2013b). According to Bhattarai, Duffy, & Raymond (2005), low-income families have increased participation in private food assistance and decreased their reliance on the federal food stamp, currently known as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) program. The purpose of their research was to assess the influencing factors on private food pantry and federal food assistance program participation. With the average food pantry usage of two years per individual, it has become a regular source for food supply instead of an emergency food supply option. Greger, Maly, Jensen, Kuhn, & Monson (2002) designed a project that analyzed the nutritional content of 53 packets of basic food packets from two selected food pantries by using Nutritionist 5 (version 2.1, 1999, First Data Bank, San Bruno, California). Their research indicated that most food pantry boxes were not providing adequate amounts of vitamins and minerals. Due to the length of time that people utilize emergency food supplies at food pantries, they are at higher risk for nutrient related diseases and nutrient deficiencies. According to Greger et al. (2002) the role of a food bank should be to supply a specific quantity of food and an adequate quality of food.

Food Insecurity

The Life Science Research Office defines food insecurity: "When households have limited access to sufficient safe and nutritionally adequate food 'without resorting to emergency food supplies, scavenging or stealing'" (as cited by Handforth, Hennink, & Schwartz, 2013). In 2010, as stated by the Position of the American Dietetic Association, 14.6 percent of American households, or 49.1 million individuals, experienced food insecurity (Holben, 2010). Income is one of the largest contributors to food insecurity. Fifty-three percent of people under the federal poverty level in America are food secure, and 47 percent of people under the federal poverty level are food insecure (Nord, Coleman-Jensen, Andrews, & Carlson, 2010). Additional studies from Nord et al. state that the prevalence of food insecurity is four times higher in households with income below 185 percent of the poverty line than in households of higher income. However, some households with annual incomes greater than the federal poverty line experience food insecurity. This indicates that additional factors such as the addition of a family member, divorce, or job loss can affect the food security of an individual. Additionally, Hispanic households, Black non-Hispanic households, and female-headed households are more likely to be food insecure. Food insecure individuals have a lower intake of calcium, protein, vitamin A, vitamin B-6, phosphorus, thiamin, riboflavin, and niacin (Holben, 2010). Consequently, they are at higher risk for nutrient related diseases.

Feeding America

Many food insecure individuals are assisted through the Feeding America network, which is comprised of 202 regional food banks and many subsidiary food pantries (Feeding America, 2013b). It is the largest non-profit organization in the United States. It distributes food for 37 million Americans through governmental programs such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), the Summer Food Assistance Program, the Emergency Food Assistance Program, and the Commodity Supplemental Food Program. Additional programs include the Child and Adult Care Food Program, the National School Lunch Program, the School Breakfast Program, and the Women, Infants, and Children program. Additionally, it provides food to regional food banks and subsidiary local food pantries. Its mission is to create a network for food banks to fight hunger together.

The Feeding America organization (formerly America's Second Harvest) has both local and national roles in supplying food banks (Feeding America, 2013b). Locally, the members of Feeding America work to obtain food from local farms, retail sources, manufacturing businesses, and the government. With these donations and purchases, the food is distributed through food pantries, faith organizations, and other agencies in each community. On a national level, the Feeding America office coordinates national food donation initiatives from large manufacturers and the government. The foods acquired from the sources are used by regional food banks, which then supply local food pantries with their foods.

Food insecurity affects the nutritional status of older adults

Of all food pantry clients at Feeding America, 18.6 percent of households have older adults in the home (Feeding America, 2013c). Because this population of clients over the age of 65 is expected to increase by 36 percent in the next ten years, it is an important population to consider for nutritional deficiencies. All elderly adults, either food secure or food insecure, are at an increased risk of hypertension, congestive heart failure, diabetes, dyslipidemia, coronary artery disease, osteoporosis, malignancies, and renal failure (United States Department of Health and Human Services, 2000). It is estimated that the number of elderly Americans that are food insecure will increase by 50 percent in 2025 (Feeding America, 2013c). Elderly clients that are food insecure have lower kilocalorie, protein, carbohydrate, saturated fat, niacin, riboflavin, vitamin B-6, vitamin B-12, magnesium, iron, and zinc intake than food secure elderly Americans (Lee & Frongillo, 2001). This increasing population of elderly Americans, both food secure and insecure, necessitate additional nutrition intervention programs (Kamp et al., 2009).

In general, inadequate intakes of recommended dietary allowances (RDA) increases the risk of disability, leads to more frequent infections, and increases disease complications (Lee & Frongillo, 2001). Lee and Frongillo stated "A decline in nutritional status is not an inevitable part of the aging process or of disease; rather, it is environmentally determined and frequently results from inattention to risk factors that can be improved by appropriate nutrition intervention" (p. 1508). According to the Academy of Dietetics and Nutrition, older adults should be provided a nutritionally adequate diet, even those that are utilizing governmental and food pantry programs:

It is the position of the American Dietetic Association, the American Society for Nutrition, and the Society for Nutrition Education that all older adults should have access to food and nutrition programs that ensure the availability of safe, adequate food to promote optimal nutritional status. . . . The growing number of older adults, the health care focus on prevention, and the global economic situation accentuate the fundamental need for these programs (Kamp et al., 2009).

Commodity Supplemental Food Program

The primary governmental resource designated for providing supplemental nutrition for an elderly adult is the Commodity Supplemental Food Program (CSFP). This program is covered under the Agriculture and Consumer Protection Act of 1973 Part 247 and the most recent Farm Bill. This bill, called the 2014 Agricultural Act, was passed in February 7, 2014 (United States Department of Agriculture, 2013c). The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) organizes the CSFP by making purchases of nutrient-dense foods at wholesale prices. The CSFP distributes these foods to each state at regional food banks, which then distribute the foods to local food pantry and faith-based food organizations. The food pantries and faith-based agencies supply food products and educate individuals. Seniors over the age of 60 may be eligible for this program through the USDA if their income is less than 130 percent of the Federal poverty level (United States Department of Agriculture, 2013a). For 2013, the income that is less than 130 percent of the Federal poverty level is $14,937 for a household with one person, and $20,163 for a household with two people. For these eligible individuals, the CSFP program is designed to provide nutritious products that will decrease nutrient-related health problems.

Nutritional Content of Food Boxes

The foods provided in the CSFP food boxes focus on providing nutrients that are often deficient in low-income individuals. There is not a specific recommended daily allowance that the CSFP is trying to meet. Those utilizing the CSFP are able to receive ready-to-eat cereals, low-sodium canned vegetables, non-fat dry or ultra-high temperature milk, unsweetened juices, canned fruit in light juices, canned meats, cheese, potatoes or rice, peanut butter, and dry beans (United States Department of Agriculture, 2013b). Elderly CSFP boxes contain two packages of ready-to-eat cereal or farina, one package of rolled oats, two containers of juice, one or two cans of meat, and 64 oz of ultra-high-temperature pasteurized milk or non-fat dry milk. Additionally, the CSFP boxes contain one package of peanut butter, one package of dry beans, one package of dehydrated potatoes, rice, or pasta, 2lb package of cheese, two cans of fruit, and four cans of vegetables. The products provided in these packages are selected for their nutrient density by the USDA Food and Nutrition Service. According to Minnesota's CSFP coordinator Mary Clare Rieschl, the boxes provide a wide variety of nutrients that would be deficient in low-income individuals (M. C. Rieschl, personal communication, May 15, 2013). Rieschl indicated that because low-income individuals are often low in vitamin A, vitamin C, and calcium especially, packages are created to include these items. Additionally, packages typically include two cans of green beans, two cans of tomatoes per month, and 100 percent apple and orange juice (M. C. Rieschl, personal communication, May 15, 2013). There is no specific nutritional ranking system used for these packages. It may be helpful to the nutritional status of food pantry clients if food pantry boxes were modeled after CSFP boxes.

Nutrition Profiling

For those that need additional resources to be food secure, food products are available in many cities at local food pantries. There are about 61,000 food pantries associated with Feeding America and additional independent food pantries (Feeding America, 2013a). In order for food pantries to provide nutritionally complete food packages to elderly clients, a nutrition ranking system could be utilized. A nutrition ranking system or nutrient profiling system is defined by the World Health Organization (2011) as ". . . the science of classifying or ranking foods according to their nutritional composition for reasons related to preventing disease and promoting health" (para. 1). The goals for this system are to increase the client's knowledge of a food's healthfulness for client-choice food pantries and to create a standardized checklist that could be used to guide an elderly client food package. Researchers have found that most food packages contain inadequate amounts of calcium, vitamin A, and vitamin C (Greger et al., 2002). Deficiencies in calcium can cause osteoporosis (loss of bone density), deficiency in vitamin A can cause blindness, and deficiency in vitamin C can weaken the immune system. Because of these micronutrient inadequacies, it is important to utilize a checklist for these nutrients. The specific items on the checklist would depend on the pantry's ability to acquire products containing vitamin A, vitamin C, and calcium. It would also be helpful to incorporate low-fat and low-sodium products into the food choice due to the increased risk of hypertension, congestive heart failure, diabetes, dyslipidemia, coronary artery disease, osteoporosis, malignancies, and renal failure in elderly clients (Mahan, Escott-Stump & Raymond, 2012). A low-fat and low-sodium diet has been found to decrease the incidence of hypertension, congestive heart failure, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and coronary artery disease. These diseases can be reduced by providing food insecure individuals adequate energy, vitamin, and minerals (Handforth et al., 2013).

Due to the dramatic incidence of nutrient-related diseases in food insecure clients, some food banks are creating programs to increase healthy food options and client knowledge (Handforth et al., 2013). They are focusing on analyzing the nutritional quality of the food offered (Greater Pittsburgh Community Food Bank, 2011a). "The paradigm shift to emphasize the distribution of healthy products at food banks has the potential to address both food insecurity and malnutrition in vulnerable populations" (Handforth et al., 2013, p. 411).

Nutritional Ranking Systems

The most highly utilized system of nutrition ranking used in food banks is the Choose Healthy Options Program (CHOP). The Greater Boston Food Bank, the San Diego Food Bank, The Austin Food Bank, and the Oregon Food Bank utilize this system; CHOP uses the Food and Drug Administration's (FDA) nutrition labeling facts to create a score for each individual food (Greater Pittsburgh Community Food Bank, 2011a). The CHOP goals

. . . optimize quality and quantity of healthy food available through food bank distribution channel; increase consumption of healthy food among nutritionally at-risk food recipients; utilize the CHOP food analysis tool to identify healthy food for acquisition and distribution; and educate stake holders: consumers, volunteers, agencies, donors, vendors, staff, everyone, on the value and use of food as part of a healthy diet. (Greater Pittsburgh Community Food Bank, 2011b, para. 2)

Clients of food pantries with or without a nutritional profiling system should have the opportunity to make informed nutrition choices through the implementation of a nutrition profiling system.

The CHOP system could be used to create a checklist for food pantry boxes that contain less sodium and fat, and higher amounts of vitamin A, vitamin C, and calcium than the current food boxes. These boxes would be beneficial for the elderly clients as well as the general population. According to the system, products that have more vitamins, minerals, and fiber coupled with less fat, sodium, and added sugars would be labeled with a 1 (suggested to be chosen frequently). If a checklist had a required number of products with a ranking of 1, 2, and 3, the nutritional content could be more closely monitored while maintaining flexibility of product choices (Greater Pittsburgh Community Food Bank, 2011a).

The total benefits of nutrient profiling have not yet been determined by repeated research. However, some benefits include providing clients with knowledge of the healthfulness of their food and providing a system to evaluate the pantry's ability to provide nutritious foods (Greater Pittsburgh Community Food Bank, 2011a). Alongside these benefits are barriers that may influence the implementation of a nutrient ranking system in a local food pantry. These barriers include lack of storage space for nutrient dense foods such as fresh produce, meats, and dairy; fear of losing donations if the pantries only utilized nutrient dense products; clients lacking knowledge of how to prepare some of the more nutrient dense foods; differences in client preference; and lack of desire to change the organization system of the pantry (Campbell, 2010).

Summary

The role of the food pantry has evolved from a short-term food supply to a long-term resource. When clients depend on these food products for a long period of time, they are at higher risk of nutrient-related chronic diseases and nutrient deficiencies. In order to decrease the risk of chronic disease in this population, food pantries may address nutrient deficiencies through nutrition profiling systems (Handforth et al., 2013).

Methods

This nutritional profiling research study utilized a survey of the three subsidiary food pantries to determine the agency's desire and ability to implement a nutrient profiling system. Due to the current use of nutrient profiling systems in some regional food banks, it may be possible to implement a similar system in local food pantries. Additional research was completed to analyze what percentage of an elderly client's nutrient needs are met through food pantry boxes. This helped determine what nutrient deficiencies were present and what type of nutrient profiling system would be most effective in that location.

This study consisted of qualitative interviews and a quantitative nutritional analysis of food pantry boxes. Qualitative interviews were conducted with three directors of subsidiary food pantries, two directors of regional food banks, and one regional director of the Commodity Supplemental Food Program (CSFP). Each interview consisted of questions from the ten-question survey (See Appendix A), developed by the researcher for the purpose of obtaining information on the pantries knowledge and implementation of nutrition profiling. Five interviews were conducted over the phone, and one interview was conducted in person. These took place on November 5, 2013, November 8, 2013, November 14, 2013, two on November 19, 2013, and December 9, 2013. The information was transcribed and reviewed for recurring themes.

The three subsidiary food pantries were studied as case-control study agencies. These agencies were located in two Midwestern cities. When designing the study these pantries were selected due to their partnership with Feeding America as well as their designation as a full or partially client-choice food pantry. Each pantry was given a ten-question qualitative survey (See Appendix A). This survey was administered over the phone or in person, and consisted of 10 questions regarding food donations, food pantry organization, food box components, and nutrition profiling. The two regional food banks were selected because they were partnered with the selected local food pantries in the two Midwestern cities. Lastly, the interview with the regional director of the federal Commodity Supplemental Food Program was selected due to its partnership with one of the Midwestern cities.

The quantitative analysis of the nutrient content of a food pantry box was completed from December 9, 2013 - January 9, 2014. The food product information was obtained by visiting each subsidiary location and recording what products each pantry client selected. This information was obtained on November 22, 2013, November 27, 2013, and December 20, 2013. For one pantry, the client was only able to choose some of their products because volunteers had prepackaged part of the food boxes. Because of this, the investigator determined the box content by recording which products were available according to one's household size. Ten boxes from each subsidiary food pantry were recorded for a 1-4 person household as well as one box from the CSFP. Any boxes for a household larger than four had the amounts divided by two in order to keep the averages of each box accurate. The information regarding the content of the CSFP was located on the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Food and Nutrition Service website. This information was entered into the online nutrition analysis software from the USDA, SuperTracker, to determine the nutrients in the CSFP food boxes.

In order to utilize the software, the contents of each food box were entered as one day's intake of food. From the content of these boxes, each individual food item (or closely similar product) was entered into the software, including as many servings as the package contained. Secondly, the food box (entered as one day's food intake) was exported into the Microsoft Excel program. In this program each box's nutritional content was divided by the number of days that it served the pantry client. For Pantry 1, the clients were able to obtain a food box once per week. Therefore the nutritional content was divided by seven days. For Pantry 2, Pantry 3, and the CSFP box, each client was able to obtain a box once per month. The nutritional content of these boxes was divided by 31 days. Each of the 10 boxes was analyzed from each subsidiary food pantry, and one box was analyzed from the CSFP. After the samples (n=31) were analyzed, the investigator averaged each pantry's 10 boxes to determine an average amount of nutrients provided. This information was divided by the Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) for a moderately active male over the age of 51. Percentages from each location were then compared for their values in calories, grams of protein, carbohydrate, and fat; milligrams of calcium, sodium, and iron; and micrograms of Vitamin A and Vitamin C.

Results

Through this investigation, the current practices of nutrition profiling were determined for three subsidiary food pantries, two regional food banks, and the CSFP. Along with this information, the percentage of RDA was determined for kilocalories, fat, protein, iron, calcium, sodium, Vitamin A, and Vitamin C in each food box for a moderately active male over the age of 51.

Research Questions

The following questions were used in this study:

- What nutrition profiling systems are currently being utilized in the Commodity Supplemental Food Program?

- What is the process by which regional food banks complete nutritional profiling?

- Would subsidiary food pantries desire to implement a nutritional profiling system?

- What percentage of an elderly client's daily average requirement of kilocalories, fat, protein, iron, calcium, sodium, Vitamin A, and Vitamin C is provided by local food pantry boxes?

The regional director of the CSFP indicated that there were no nutrition profiling systems utilized by the CSFP. This answered the first question. The box contents were determined at the start of the program in 1969, and were based on nutrients found to be deficient in young mothers and the elderly in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). The food box contents have changed three times since the beginning of the program. A change in 2010 was the inclusion of lower sodium canned vegetables, lower sugar canned fruits, and whole grain products (M. C. Rieschl, personal communication, May 15, 2013).

The two regional food banks in the study did not have a nutrition profiling system in place. This answered the second question of "What is the process by which regional food banks complete nutritional profiling?" They did not utilize nutrition profiling and therefore had no process. At these locations a registered dietitian analyzed the nutritional content of their products using a nutrition analysis software. However, Regional Food Bank 1 created and implemented a nutrition profiling system, named Smart Check, in an offsite affiliated food pantry. After the implementation of Smart Check the Regional Food Bank 1 conducted a focus group to investigate program success. It was found that the clients did not understand nor utilize the information as much as Regional Food Bank 1 directors desired. Regional Food Bank 2 had an onsite food pantry but did not utilize a nutrition profiling system. Both food bank nutrition directors stated that they might be interested in implementing a nutrition profiling system for labeling their products so that subsidiary food pantries that purchase those products could use the pre-organized system. The following table indicates the frequency of the types of nutrition profiling systems present in the selected Regional Food Banks 1 & 2 and the Commodity Supplemental Food Program.

Table 1

Type of Nutrition Profiling System for Regional Food Banks 1 & 2 and the Commodity Supplemental Food Program

Frequency

Percentage

Boston Choosing Healthy Options Program

0

0

My Plate System

0

0

Independent System

1

33.3%

None

2

66.6%

The results from the 10-question survey provided interesting insight into each subsidiary food pantry. If regional food banks implemented a nutrition profiling system for labeling of their products, all three subsidiary food pantries would be interested in utilizing a nutrition profiling system. This answers the third question of "Would subsidiary food pantries desire to implement a nutritional profiling system?" However, two of the three directors of the pantries stated that they do not have enough time, resources, or volunteers to implement a system independently.

Additional results of the survey found that only two of the three pantries were familiar with the term nutrition profiling and that food box components were generally based on the available product. This indicated that the primary concern of food pantries is not the nutritional needs of a specific age group, but rather feeding all clients whatever products are available and financially reasonable. Table 2 indicates what the food pantries and the CSFP consider most important for creating their food boxes.

Table 2

Which factor is most important in providing food box components for Pantries 1-3 and the CSFP?

Frequency

Percentage

Age Group

0

0

Family Size

1

25%

Nutrient Composition

1

25%

Available Product

2

50%

The final question of "What percentage of an elderly client's daily average requirement of kilocalories, carbohydrate, fat, protein, iron, calcium, sodium, Vitamin A, and Vitamin C is provided by local food pantry boxes?" are summarized in Figures 3 – 8.

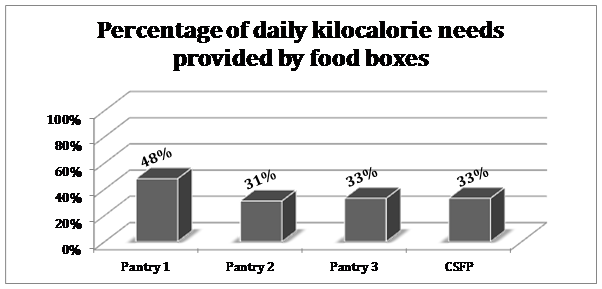

Figure 3. Percentage of daily kilocalorie needs provided by food boxes

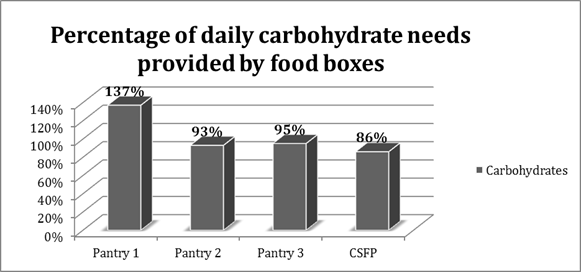

Figure 4. Percentage of daily carbohydrate needs provided by food boxes

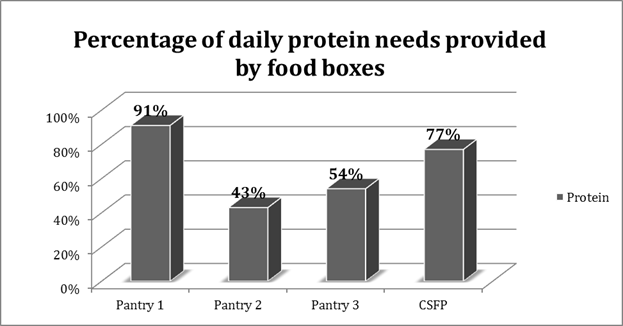

Figure 5. Percentage of daily protein needs provided by food boxes

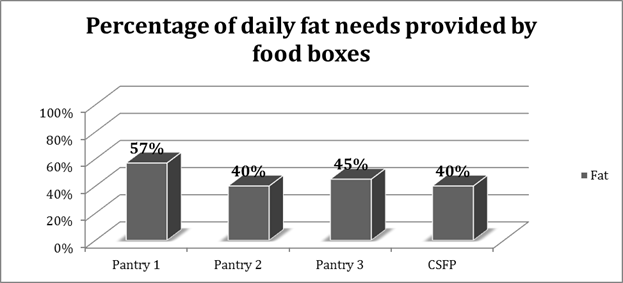

Figure 6. Percentage of daily fat needs provided by food boxes

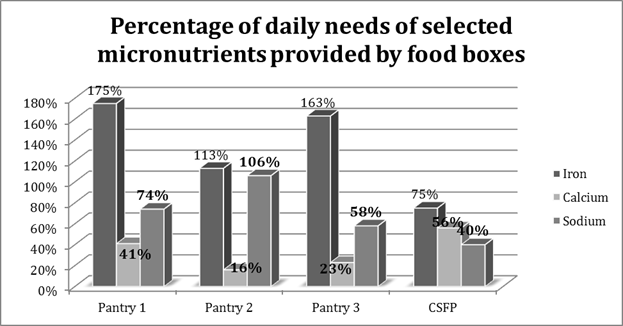

Figure 7. Percentage of daily needs of iron, calcium, and sodium provided by food boxes

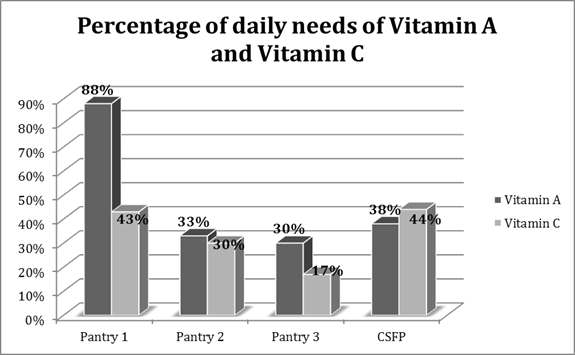

Figure 8. Percentage of daily needs of Vitamin A and Vitamin C provided by food boxes

These results indicated that there is a low prevalence of nutrition profiling systems being utilized by the sample of the regional food banks, subsidiary food pantries, and the CSFP. Additionally, these results indicated that average food boxes samples provided 36 percent of kilocalories, 103 percent of carbohydrates, 66 percent of proteins, and 46 percent of fat. The average food box sample provided 34 percent of Calcium, 131 percent of Iron, 47 percent of Vitamin A, and 34 percent of Vitamin C of the Recommended Dietary Allowance for an elderly male client.

Discussion

This study concluded that there is a lack of nutritional profiling systems in the Midwestern region of the United States. The first hypothesis predicted that the CSFP does not have a nutritional profiling system but that the regional food banks would utilize either the CHOP system or an independently created system. It was found that neither the CSFP nor the regional food banks utilized a nutritional profiling system. This is largely due to the expense and time commitment to develop a system. Due to the absence of systems, affiliated pantry clients lack information needed to make better choices, and the food pantry leaders lack the information needed to provide the clients the most nutritionally complete component. If clients do not know which foods are healthiest, why healthy foods are important, or how to prepare those foods, the nutritional profiling system would not be useful. One director mentioned that signs were made to signify the healthfulness of some products but not many clients were interested. The directors of all the organizations emphasized the need for education for the clients in order for nutritional profiling systems to be effective. "It is about getting info to the client so they can change behavior" (Regional Food Bank 1, personal communication, December 9, 2013).

The second hypothesis predicted that food pantries desire to implement a nutritional profiling system in order to increase the nutritional quality of their products. However, the lack of time and volunteers make implementing an independent system arduous. Many pantries rely on one-time volunteers to help run their pantry. They are not able to educate a large number of volunteers on how to analyze food products that are donated or purchased nor do they have time to label each product that enters the pantry. All three pantry directors stated that if their regional banks labeled the products they would be able to implement the system more practically. According to one director of subsidiary food pantry, this would be challenging because available foods frequently change. Consequently, the regional food banks would have a large task of labeling the variety of foods in their warehouses. It would be easiest for the regional food banks to implement a ranking symbol on food products for which they already create labels rather than have food pantries put ranking symbols on the products.

A suggestion from one regional food bank director was to implement the MyPlate nutritional profiling system. The purpose of using this system is that the symbol is already recognizable (See Figure 9). This would decrease confusion among pantry clients because the MyPlate program is familiar to the general population. Each product that comes through the food bank would be marked to indicate whether the food was a grain, protein, dairy, fruit, or vegetable product. The pantry would have stickers or cards to place on the product to advertise its food group. If a system was created by the regional food banks that was easily recognizable, subsidiary food pantries could put it into place along with educating food pantry volunteers and clients.

Figure 9. MyPlate graphic

Lastly, it was predicted that the sample of food boxes would provide 50 percent of an elderly individual's daily needs in the selected macronutrients, but less than 50 percent in the selected micronutrients. As shown in the results, the only macronutrient that every agency provided greater than 50 percent was carbohydrates. No other macronutrient was provided in amounts greater than 50 percent for all four agencies. In regards to micronutrients, it was interesting to note the high amounts of iron provided. One might expect iron amounts to be lower because fewer meat products are available, but it might be higher due to the consumption of iron-fortified products such as ready-to-eat cereals and breads. Consequently, the bioavailability of the iron sources is unknown. This research confirmed previous research studies stating that most food pantry boxes have lower amounts of calcium, Vitamin A, and Vitamin C (Greger et al., 2002). A suggestion for increasing calcium, Vitamin A, and Vitamin C would be to provide more ultra-high temperature shelf stable milk for calcium needs, fresh or canned carrots for Vitamin A, and citrus fruits or juice for Vitamin C. After pantries are made aware of nutrient deficiencies they can analyze which products their pantry could offer to provide a nutritionally complete food box for pantry clients, especially the vulnerable elderly population.

Limitations

The primary limitation for this study was the small sample size. The CSFP, two regional food banks, and three food pantries participated. Due to time constraints and pantry participation, the size of the sample of food boxes (n=31) was limited. In spite of the small sample size, the averages of the food boxes provided an approximate amount of nutrients offered in each box. A larger sample size could have made the nutrient amounts more accurate.

The second limitation for this study was the use of the SuperTracker nutrition analysis software. This software does not contain every product offered in the food boxes and makes it difficult to enter large amounts of one product. Any products that were not listed were entered as a similar product. It would be better to use more extensive software that included the nutritional information for every product and included more serving sizes. However, SuperTracker was free of cost and easily accessible.

Recommendations for further studies

A recommended continuation of this study would be to actually install a nutritional profiling system in a food pantry. This could be MyPlate, an independently created, or a regional food bank system. After implementation, the investigator could analyze the use of the program by clients, determine the level of education required to understand the program, and create an educational system that could be used in collaboration with the nutritional profiling system.

An additional suggestion would be to analyze the nutritional content of a larger sample of food pantries across the United States. This would provide a better perspective of the deficient nutrients in all of the food pantries and help restructure food pantry boxes in the future. Lastly, a suggestion would be to analyze the nutritional content of a larger sample of food boxes. It has been shown that food pantries desire to provide their clients with the most nutritionally complete boxes with the financial resources available. If they are aware of what foods they are missing they could better meet the challenge of feeding millions of individuals across the United States each day.

Conclusion

It was observed through this study that food pantries desire to provide their clients with nutritious food. Food pantries desire to implement systems that will provide clients with greater knowledge of the nutritional value of their products. Chronic diseases are more prevalent in food pantry clients (Lee & Frongillo, 2001); however, providing good nutrition to clients could combat these diseases.

Food pantries are providing their clients with the food products that provide the most nutritious products within the food pantry budget and with the products clients and families desire to eat. These foods may be deficient in some macronutrients and micronutrients, but they are still providing kilocalories. When individuals are hungry, they may not have a preference for healthful products. Oftentimes pantry clients are just trying to feed themselves and their families. It is acknowledged that offering more nutritious products is more complicated than detecting nutrient deficiencies in food boxes. Further studies can help reduce nutrient deficiencies in food pantries by identifying what is needed.

References

Bhattarai, G., Duffy, P. A., & Raymond, J. (2005). Use of food pantries and food stamps in low-income households in the United States. Journal Of Consumer Affairs, 39(2), 276-298. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6606.2005.00015.x

Campbell, E. (2010). Implementing a nutrition quality system. University of California at Berkeley. Retrieved from http://mazon.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/02/Implementing-a-Nutrition-Quality-Rating-System1.pptx.

Feeding America (2013a). About Feeding America. Retrieved from http://feedingamerica.org/press-room/press-releases/charitable-faith-leaders-respond-house-farm-bill-inclusion-severe-cuts-food-assistance.aspx

Feeding America (2013b). How our network works. Retrieved from http://feedingamerica.org/how-we-fight-hunger/our-food-bank-network/how-our-network-works.aspx

Feeding America (2013c). Senior hunger. Retrieved from http://feedingamerica.org/hunger-in-america/hunger-facts/senior-hunger.aspx

Greater Pittsburgh Community Food Bank (2011a). Choose Healthy Options Program (CHOP™): Development of a nutrition policy. Retrieved from http://www.cloudnutrition.net/?page_id=180

Greater Pittsburgh Community Food Bank (2011b). Choose Healthy Options Program (CHOP™): What is CHOP? Retrieved from http://www.cloudnutrition.net/?page_id=148

Greger, A., Maly, N., Jensen, J., Kuhn, K., & Monson, A. (2002). Food pantries can provide nutritionally adequate food packets but need help to become effective referral units for public assistance programs. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 102(8), 1126–1128.

Handforth, B., Hennink, M., & Schwartz, M.B. (2013). A qualitative study of nutrition-based initiatives at selected food banks in the Feeding America network. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 113(3), 411-415.

Holben, D. (2010). Position of the American Dietetic Association: Food insecurity in the United States. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 110(9), 1368-1377. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2010.07.015)

Kamp, B., Wellman, N., & Russell, C. (2009). Position of the American Dietetic Association, American Society for Nutrition, and Society for Nutrition Education: Food and nutrition programs for community-residing older adults. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 110(3), 463-472.

Lee, J. S., & Frongillo, E.A. (2001). Nutritional and health consequences are associated with food insecurity among U.S. elderly persons. Journal of Nutrition, 131(5), 1503-1509.

Mahan, L. K., Escott-Stump, S., & Raymond, J. L. (2012). Krause's food and the nutrition care process. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders.

Nord, M., Coleman-Jensen, A., Andrews, M., & Carlson, S. (2010). Household food security in the United States, 2009. Economic Research Report, 108, 1-62

Rose, D. (1999). Economic determinants and dietary consequences of food insecurity in the United States. The Journal of Nutrition, 129(2), 517S-520S. Retrieved from http://jn.nutrition.org/content/129/2/517S.full.

United States Department of Agriculture (2013a). Commodity supplemental food program: Income guidelines for 2013. Retrieved from http://www.fns.usda.gov/fdd/programs/csfp/CSFP_2013_Income_Guidelines.pdf

United States Department of Agriculture (2013b). Commodity supplemental food program: Revised food package maximum monthly distribution rates and replacement of evaporated milk with one percent ultra high temperature (UHT) fluid milk, dated January 13, 2011. Retrieved from http://www.fns.usda.gov/fdd/programs/csfp/CSFP_Rev_Max_Monthly_Dist_Rates_UHTMilk.pdf

United States Department of Agriculture (2013c). Commodity supplemental food program: Law and Policy. Retrieved from http://www.fns.usda.gov/fdd/programs/csfp/welcome_packet/CSFPSection4.pdf

United States Department of Health and Human Services. Committee on Nutrition Services for Medicare Beneficiaries. Food and Nutrition Board (2000). The role of nutrition in maintaining health in the nation's elderly: Evaluating coverage of nutrition services for the Medicare population. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

World Health Organization (2011). Nutrient profiling. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/nutrition/topics/profiling/en/

Acknowledgements

I would like to express appreciation and thanks to my academic and research advisor, Dr. Catherine Anstrom for her mentorship. She offered tremendous encouragement in the project, and her willingness to work with me through the process was priceless. In addition, I would like to express thanks to Dr. Kristian Veit for his assistance in data analysis. To my peers Carly Wade and Alex Colwell, thank you for your many hours of work in analyzing nutritional data. Your help was a great catalyst for the project. I would like to thank the six directors of the food banks, pantries, and the Commodity Supplemental Food Program for their willingness to be interviewed. Lastly, I would like to thank Olivet Nazarene University Family and Consumer Science Department for the opportunity to complete this research project.

Appendix A

Food Pantry Survey

- Is the food that comes into your facility:

- Purchased

- Donated

- Both

Comments:

- What foods do you purchase? Circle all that apply:

- Milk and milk products

- Meat, fish, fowl, eggs, beans

- Fresh produce

- Cereals, breads, pastas

- Processed Foods: Boxed dinners such as mac and cheese, rice dinners, etc.

- Butter and margarine

- Dessert type products: Cookies, cakes, pies, etc

- Beverages: sodas, coffee, powdered drink mixes

Comments:

- If foods are purchased, from where are they purchased?

- Government commodities

- Parent Food Banks

- Northern Illinois Food Bank

- Second Harvest

Comments:

- What foods are donated? Circle all that apply:

- Milk and milk products

- Meat, fish, fowl, eggs, beans

- Fresh produce

- Cereals, breads, pastas

- Processed Foods: Boxed dinners such as macaroni and cheese, rice dinners, etc.

- Butter and margarine

- Dessert type products: Cookies, cakes, pies, etc

- Beverages: sodas, coffee, powdered drink mixes

Comments:

- If products are donated, who donates these products?

- Individuals

- Restaurants

- Grocery Stores

- Food producers

- Government programs

Comments:

- What is your system for categorizing your products?

- By food group: Grains, fruits, vegetables, protein foods (meats and beans), and dairy products.

- By perishable or nonperishable products

- By packaging material: canned goods, boxes item, bagged items

Comments:

- What are the food box components based on?

Circle all that apply, and rank importance from 1-4.

- Based on age group

- Based on family size

- Based on nutrient composition

- Based on available product

Comments:

- Do you have a system for evaluating the nutrient content of your foods?

- If yes, briefly explain the process

- Have you heard of the process called nutrient profiling?

Comments:

- Would you be interested in implementing a nutrient profiling system for a client-choice food pantry?

Comments:

|