Small Scale Living and the Meaning of Home

Shelby Kiser

Kansas State University

Key words: Tiny Homes, Compact Living, Meaning of Home, Downsizing, Small Scale Living, Pocket Neighborhood

Abstract

In current United States housing trends, prices and square footage are rising as personal satisfaction and fulfillment decline. This is a result of people assuming that upgrading their living standards will provide instant gratification, but it may only lead to unhappiness. As our houses grow larger, so do our debts. During the most recent economic down turn a renewed interest in small scale living arose. People began seeing the value in downsizing, reducing debt, and living more sustainably. Evaluating the functional, environmental, economic, and psychological aspects of living small will help determine what challenges one will face by reconsidering how and where they live. With a deeper understanding of the connections and value of home, designers are able create dwellings that can positively influence the users. The potential impact starts with designers, therefore it is crucial to be educated and actively implementing this knowledge into designs.

Beginning in the 1960’s, people for simple and clutter-free living began advocating for the needs of the environment (Kahn & Welch, 2012). Since then living small has developed into much more. When the economy failed in 2008, this debt-free alternative to housing rose in popularity. The key to living small is about downsizing. Small scale living comes in many forms such as apartments, single family homes, and portable housing. Overall, downsizing to a smaller home is more than purging belongings and lowering your environmental impact, it takes mental awareness and a well-designed space. To appreciate how and why people are choosing to go tiny, we must understand the meaning of home. More extravagant and abundant space does not enhance one’s ability to feel at home or experience happiness. According to personal accounts, smaller homes provide a chance to relate to the space and discover the rewards of individualized homes that reflect identity, belonging, and self-expression (Grinberg, 2012).

Literature Review

A combination of books, magazines, newspapers, and journal articles provided sources on small scale living. Keywords and phrases such as “tiny homes,” “meaning of home,” “compact living,” and “space efficient homes” helped sort through to useful information. Using date restrictions of 1980 to present insured the sources to be relevant. A range of several decades allowed current material to be compared with historical data. Building Green, Avery Index to Architectural Periodicals, GreenFILE, and ProQuest were commonly consulted databases. The following sections summarize many of the key issues related to understanding small scale living and the relationship that people have with their homes.

Human Relation with Home

The mention of home brings up a plethora of feelings, places, or scenarios to different people. Exploring what home means varies from person to person. Culture, background, religion, and family status contribute to one’s definition. “In English, the term ‘home’ derives from the Anglo-Saxon word ‘ham,’ meaning village, estate or town” (Mallett, 2004, p.4). An example of a definition of home according to Mallett (2004):

Home

n. 1. The place or a place where one lives

2. a house or other dwelling

3. a family or other group living in a house or other place

4. a person’s country, city, birthplace, a residence during one’s early years, or a place dear to one (p.1)

In determining a definition of home, it is crucial not to create a rigid description. Each person differs in their experiences and opinions. Since home is a physical place with social interactions and emotions attached, not everyone will express their concept of home in exactly the same terms. Personal meanings as well as the timing in one’s life are essential to consider when developing an understanding of the attachment people have to their home, and whether it is positive or negative (Marcus, 1995, p.2-4).

Ginsburg wrote:

We make our homes. Not necessarily by constructing them, although some people do that. We build the intimate shell of our lives by the organization and furnishing of the space in which we live. How we function as persons is linked to how we make ourselves at home. We need time to make our dwelling into a home…. Our residence is where we live, but our home is how we live (as cited in Mallett, 2004, p.83)

Research in the human relations field has flourished during the past twenty years, particularly within the disciplines of sociology, anthropology, psychology, human geography, history, architecture, and philosophy. John Annison (2000) highlights the work of three researchers, Smith, Sixsmith, and Depres, all of whom extensively studied factors that create a home and non-home environment.

The first author, Sandy Smith (1994), conducted research by exploring her subjects’ answers to questions concerning their current home, other homes, non-homes, and the process of establishing a home. From this research she organized a list of essential contributors to a sense of home as well as detractors to these environments (See Table 1).

Table 1. Smith’s essential contributors to a sense of home and environment that are not homes

(Adapted from Smith, 1994, p.31-33)

|

Contributors |

Detractors |

1 |

Suitable Physical Environment |

Poor physical environment |

2 |

Positive social relationships |

Dissatisfaction with the internal social relationships |

3 |

Positive atmosphere engendering feelings of warmth, care and coziness |

Negative atmosphere within the home |

4 |

Personal privacy and freedom |

Lack of personal freedom and privacy |

5 |

Opportunities for self-expression and development |

Lack of personalization and permanence |

6 |

Sense of security |

Lack of security |

7 |

Sense of continuity |

Lack of ownership |

After her research, Smith suggested that for the occupants, “home is a complex multi-dimensional concept, which is experienced simultaneously as a physical environment, a social environment, and a place for the satisfaction of personal needs” (Smith, 1994, p.43).

One way to conceptualize home is to consider it as an equation. Home = house + x. One must separate home into the physical structure and the intangible factors. The x factor represents the social, psychological, and cultural values which a physical structure gains while being occupied as a home. While these values are subjective, several qualities will be repeated from a variety of users (Fox, 2002, p. 590).Similar to Smith, in 1986, Judith Sixsmith developed a tripartite model of home including three sections: the “personal home,” the “social home,” and the “physical home.” Along with these types of domains, Sixsmith created twenty categories of interdependent meanings attached to the concept of home (See Table 2). This list defines many aspects of what make a home to people and these characteristics are applied between the three domains. Each criteria may represent a potential “x factor” in the housing equation.

Table 2. Sixsmith’s 20 categories of interdependent meanings attached to the concept of home

(Adapted from Sixsmith, 1986, p.287)

Item |

Criteria |

Definition / Description |

1 |

Happiness |

the experience of happy events and general feelings of happiness are an integral part of home. |

2 |

Belonging |

comfort, relaxation, familiarity contribute to a sense of belonging to home |

3 |

Responsibility |

stability arising from ownership and responsibility for the home |

4 |

Self Expression |

behavior in and manipulation of the place are closely tied to ideas of home. |

5 |

Critical Experiences |

learning to be independent, formative experiences, lived through stressful periods generate deep associations with home |

6 |

Permanence |

the continuity of home. |

7 |

Privacy |

being able to control your interpersonal world by having the level of privacy desired. |

8 |

Time Perspective |

places exist as home whether in the past, present, or future |

9 |

Meaningful Places |

because of specific but not necessarily critical events taking place there. |

10 |

Knowledge |

tied to familiarity, this aspect of home emphasizes physical and social knowledge. |

11 |

Preference to return |

in terms of a locus in space |

12 |

Type of relationship |

type of relationship and personal choice over being with particular people is essential focus of this category. |

13 |

Quality of relationships |

the quality of relationships. |

14 |

Friends and entertainment |

people visiting the home who form the core of social entertainment in the home. |

15 |

Emotional Environment |

a place where there is love often signifies a home |

16 |

Physical structures |

enduring physical characteristics |

17 |

Extent of Services |

lighting, heating, household equipment, garden, tele-communications, etc. are sometimes seen as a necessary part of home. |

18 |

Architectural Style |

some homes were meaningful because of their architectural style. |

19 |

Work Environment |

working at home is sometimes a defining aspect of home. |

20 |

Spatiality |

spatial properties, the activities that those spaces allow, and their location are an important aspect of home for some people. |

The personal home is a user’s emotional connection to a physical coordinate. Feelings of security, happiness, and belonging come from a physical structure. A real space gives users a way to express themselves, create meaningful experiences, and have private moments and stability in their lives. An owner feels responsible for their property. The social home is a shared place where relationships are fostered with others. Usually, these relationships are of high-quality and importance. Friends and entertainment, as well as the emotional environment create a sense of belonging. This accepted feeling brings users comfort and relaxation. The physical home is affected by the materials, space plan, and overall combinations of the furnishings and decor. The physical and architectural style of the building impacts the human space and this idea of home. In one instance, a Spanish style home may relate to one’s ethnic background or family history to form special meaning. The conveniences or services available in this space also influence why someone calls it home. For example, if it is a formal or royal setting, users may be accustomed to maids or chefs, without these amenities they feel out of place. Overall, Sixsmith’s model gives a subjective experience from three viewpoints (Sixsmith, 1986, p.290-293; Fox, 2002, p.590-601).

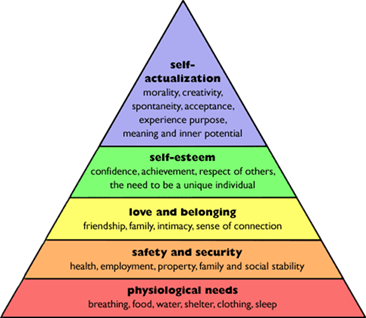

In a diverse analysis, Carole Despres (1991) sees home within the framework of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Illustrated in Image 1, beginning at the bottom of the pyramid, physiological and safety needs must be met first before moving up the ladder. These are pre-requisites to all other needs. Once these needs are met, a home can provide a suitable environment to enable fulfilment of security and love needs. Once the basics are covered we long for relationships with friends and family. Moving on to the expression of self-esteem and social achievement, we long for respect from others. At the top, one can fulfill psychological well-being through self-actualization. The tip of the pyramid represents morality, creativity, and problem solving.

Image 1. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs Pyramid

Each tier in the pyramid has elements related to criteria from Sixsmith’s 20 categories in Table 2, and the higher up on the pyramid, the more categories are represented as psycho-social needs are realized. These qualities culminate into stronger emotional bonding with place and serve as the “x factor” for the home equation. Each idea contributes to the values a physical structure needs to be understood as a home.

For example, physiological needs are served through physical structures, item 16 as well as extent of services, item 17, which are seen as necessary. Safety and security are found in the permanence (item 6) one relates to a space as well as the ability to control interactions (or privacy, item 7) because of the physical boundaries of the structure. Love and belonging are expressed in the qualities of item 2, belonging and item15, emotional environment, as well as items 12 types of relationships, 13 the quality of relationships, and 14 friends and entertainment. Graduating up the pyramid to self-esteem, the criteria advance from group experiences to individual expressions. Item 1 most directly connects as the criteria is happiness. Once one reaches this stage they feel confidence, achievement and respect. Finishing the pyramid, self-expression (item 4) and critical experiences (item 5) link with self-actualization and its subcategories to top off the similarities.

Despres, from her socio-psychological perspective, also claims that home is a significant component in defining one’s identity. Shown in Table 3, Despres constructed ten general categories of ascribed meaning of home.

Table 3. Despres 10 general categories of ascribed meaning of home

(Adapted from Despres, 1991, p.97-99)

Item |

Criteria |

Definition / Description |

1 |

Security and Control |

in the sense of individual’s feeling in control of the area and physically secure |

2 |

Reflection of Values and Ideas |

how people see themselves and want to be seen by others |

3 |

Acting upon and modifying dwelling |

the extent to which the homes provides a sense of achievement, a place for self-expression and/or freedom of action |

4 |

Permanence and Continuity |

this meaning marries the concept of home with the time dimension whereby home may be a place of memories or an environment which has become intimately familiar over a period |

5 |

Relationships with Family and Friends |

a place to strengthen and secure the relationship with people one cares for. Home is perceived and experienced as the locus of intense emotional experience, and as providing an atmosphere of social understanding where one’s actions, opinions, and moods are accepted. Ideas such as a place to share with others, to entertain with relatives and friends, and to raise children, and related to this dimension |

6 |

Center of activities |

these activities may be related to simple physiological needs such as eating or they may include pastimes or the support of other activities conducted away from the home such as work or support |

7 |

A refuge from the outside world |

this relates to the need for privacy and independence, the need to “get away” from external pressures and seek solace or at least be able to control the level and nature of demands upon one |

8 |

An indicator of personal status |

it is relatively important for people that their home show their economic status |

9 |

Material structure |

including not only consideration of the physical attributes of the actual dwelling and its aesthetic features, but also the physical characteristics of its surrounds and the neighborhood |

10 |

A place to own |

ownership is imbued with connotations of freedom, permanency, pride, and significant economic investment |

Home is a dynamic process that is ever changing and influenced by events in a person’s life (Despres, 1991, p.97-102).

Housing Trends

Understanding home and the concept of place is growing in importance in relation to housing researchers. This information helps housing researchers, developers, designers, and users gain insight into the relationships between places and people’s identities. This literature highlights a need for a more integrated approach to housing research that looks at larger scales, such as regional, national, and international, in addition to individual (Easthope, 2004, p.128). In many markets, the media influences real estate and home ownership. Commonly, advanced capitalist governments are behind promoting home ownership because it increases economic efficiency and growth. If people buy into the idea that they will be more satisfied by owning one or more homes, the government’s tactics have succeeded. As an impact, the home becomes a source of personal identity and status; a way to boast. This is concerning because it adds to the pressures of impressing others, corresponding with the growing house trend (Mallett, 2004, p.5).

The trend for large-scale housing in the United States has been an identified problem from a number of years. Most families long for the “starter castle,” according to Sarah Susanka (1998). This type of home is the large, builder grade, impersonal mansion in the typical community-lacking neighborhood people think will make them happy. In Susanka’s book “The Not So Big House: A Blueprint for the Way We Really Live,” she addresses the need for American homes to re-focus on an informal lifestyle. If we build homes that include the formal, seldom used rooms that were popular in the past, such as parlors, our space will become wasted and meaningless. In today’s world we must value quality over quantity and details over square footage. The United States Census Bureau shows information comparing square footage, room type, and age of current homes. Table 4 demonstrates that large houses are still the norm, but small houses are there!

Table 4. Rooms, Size, and Amenities-All Housing Units (NATIONAL)

|

CHARACTERISTICS |

TOTAL HOUSING UNITS |

NEW CONSTRUCTION Past 4 years |

TOTAL |

132,419 |

3,111 |

|

NUMBER OF ROOMS |

1 |

601 |

12 |

2 |

1,404 |

49 |

|

3 |

11,433 |

231 |

|

4 |

23,636 |

413 |

|

5 |

30,440 |

730 |

|

6 |

27,779 |

569 |

|

7 |

17,868 |

458 |

|

8 |

10,749 |

324 |

|

9 |

4,654 |

158 |

|

10 or more |

3,654 |

168 |

|

BEDROOMS |

None |

1,413 |

29 |

1 |

14,924 |

301 |

|

2 |

35,083 |

578 |

|

3 |

54,245 |

1,252 |

|

4 or more |

26,755 |

952 |

|

COMPLETE BATHROOMS |

None |

1,808 |

36 |

1 |

46,800 |

443 |

|

1 ½ |

16,666 |

124 |

|

2 or more |

67,145 |

2,506 |

|

SQUARE FOOTAGE Single Detached and Manufactured Mobile Homes |

Less than 500 |

973 |

26 |

500 to 749 |

2,678 |

9 |

|

750 to 999 |

6,529 |

36 |

|

1,000 to 1,499 |

20,919 |

294 |

|

1,500 to 1,999 |

20,560 |

473 |

|

2,000 to 2,499 |

14,343 |

342 |

|

2,500 to 2,999 |

7,553 |

249 |

|

3,000 to 3,999 |

7,225 |

329 |

|

4,000 or more |

4,479 |

209 |

|

Not reported |

6,762 |

173 |

|

Median Sq Ft |

1,700 |

2,200 |

(Adapted from the United States Census Bureau 2011 American Housing Survey)

*Numbers in thousands, except as indicated

In the United States, the average home size increased by 140 percent between 1950 and 2004, yet the average household shrank by 18 percent between 1970 and 2003 (Priesntiz, 2007, p. 18). This means families occupy more space with fewer individuals residing together. There has always been a negative connotation to not having the biggest, best, and newest things in America. Housing has become a competitive sport. Status has been determined by moving up and trading for something better (Bender, 2009, p. 34-39). According to Ferraro (2009), we often associate large homes with material success, power, and glamour. Small homes tend to be equal to lack of privilege, overcrowding, and inferior quality. As a result of these perceptions, we have gone through a long period of overconsumption, people living beyond their means, with houses too big and incomes too small (Kahn & Welch, 2012). Since the abrupt down-turn in the economy, many individuals and families have become more conscious about the money they spend, including their housing budget. Small homes give them a great alternative. The positives include lower energy bills, a lower carbon footprint, less to maintain, and more money towards retirement. Americans turn everything into a trend, and hopefully, the new trend to go small will stick.

Method

In order to assess the compositional differences between various classifications of homes, floor plans were obtained from www.houseplans.com. To begin this inquiry, five floor plans from four categories were selected to be examined. Tiny Homes range from 50-500 square feet. Small Homes are between 501-1,500 square feet. 1,501-3,000 square feet make up the Average Home category. Lastly, mansion-sized homes are 3,000 square feet and beyond. The selected floor plans are a mixture of Country, European, Craftsman, Modern, and Mediterranean style to understand a wide variety.

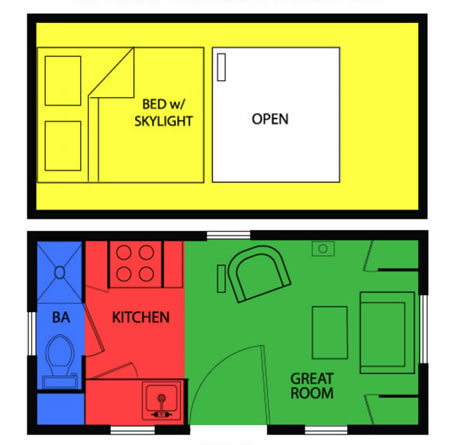

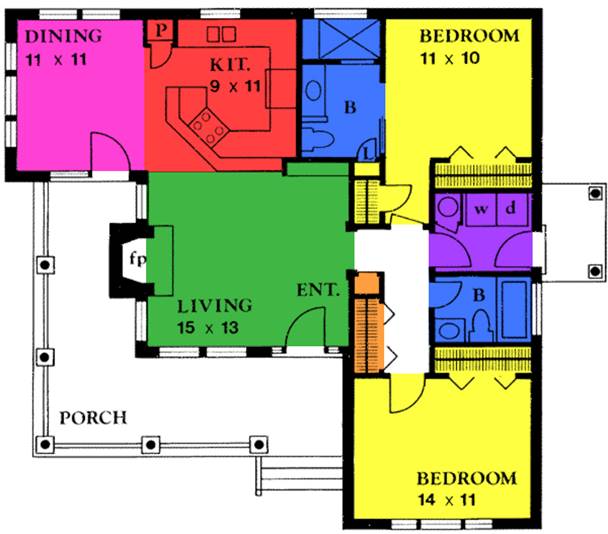

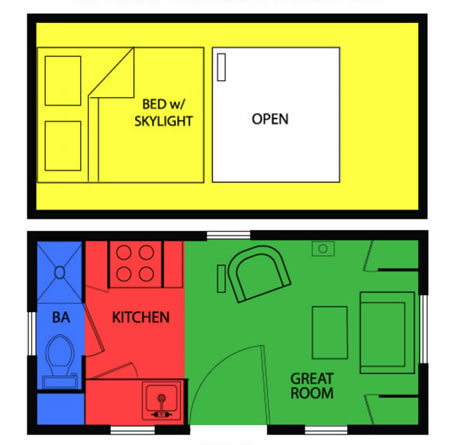

To study each floor plan, the different types of spaces were coded with a designated color blocked to mark their purpose. Images 2 - 5 demonstrate the analysis of one floor plan from each category to represent my method.

Image 2. Analysis of a Tiny Home

Tiny House: 98 Sq. Ft.

This tiny house plan features only the essential spaces with minimal features. A raised platform containing a bed creates a sleeping loft. Most of the space uses built-in cabinetry to maximize floor space and functionality. Extra storage space or a designated dining area is missing from this compact design. With a home this small, one or two people are meant to live here.

Image 3. Analysis of a Small House

Small House: 1,065 Sq. Ft.

This small house plan features two bedrooms with two bathrooms. This type of house is large enough for an eat-in kitchen and laundry room. Hall storage is a bonus as well. A kitchen with full sized appliances would be common. A couple or small family would be able to inhabit this type of design.

Image 4. Analysis of Average House Plan

Average House: 2,320 Sq. Ft.

This average house plan features three bedrooms with two bathrooms. The large master suite is a special treat in this plan. A walk-in pantry is typical to hold food for a family of 4-6 that may live in this size of home. The designated entry way and bonus nook off the kitchen are non-essential spaces in this floor plan.

Image 5. Analysis of Mansion Type House

Mansion House: 4,032 Sq. Ft.

This mansion house plan is more than enough space for the average family. It houses five bedrooms and 4 and a half bathrooms. With a plan this large, a game room, mudroom, and guest house are special features. Most closets are walk-in and all spaces are large. A family of 6 or more could live in this space.

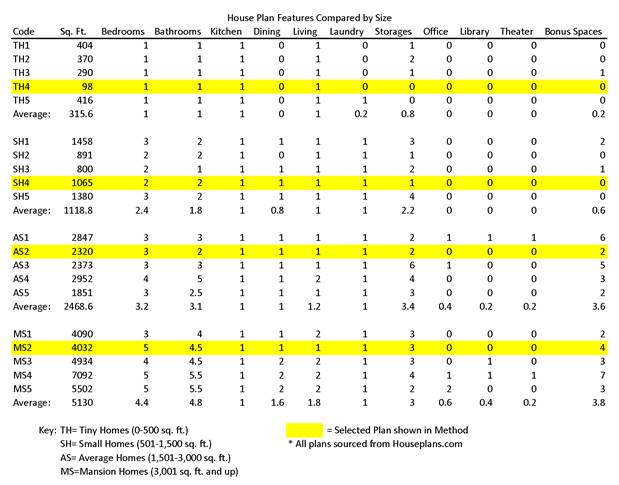

These four floor plans depict the analysis of spaces typical within the categories of plans. The table below shows the data from all 20 plans and the averages for each type of space included within the houses.

Table. 5 House Plan Features Compared by Size

Results

Table 5 displays the data from five floor plans within each size category. An average from each category gives an overview to understanding the typical numbers for each type of room. Using quantitative data provides a quick foundation to understanding of the floor plan composition without diving into the spatial analysis. The tiny floor plans contain only essential spaces and forgo laundry and a designated dining space to be more compact. The small homes’ bedrooms and storage spaces were added next. Bathrooms and bonus spaces increased most significantly for the average sized group. The mansion sized plans added more bedrooms, bathrooms, and dining spaces to their designs. To highlight an important point, the bedroom count increased in the larger floor plans, but as mentioned before, the average household size has been decreasing. This supports the research saying, people believe these extra amenities are deemed necessary by society to portray a specific image, but are seldom utilized.

The floor plan diagrams demonstrate as the footprints grew in size, the number of bedrooms and bathrooms were the first to be added when comparing all categories to one another. Laundry and storage spaces were the second largest category to grow between tiny homes and small homes. When diving into average homes the bonus spaces increased the most. Foyers, hearth room spaces, and offices were the most popular additions. When plans were over 3,000 square feet, they had multiple dining spaces and living rooms, as well as libraries and theaters. Bonus spaces capture the non-essential functions that satisfy certain hobbies or interests of the users. These rooms serve a wide variety of purposes such as exercise rooms, game rooms, workshops, and music rooms. These larger spaces likely translate to the trends of the desire to have more space around them to convey their status. Analyzing and recording data from all sizes of homes helps define the way houses grow and contract when appropriate. After recording data from 20 house plans ranging from 98-7,092 square feet, inferences can be made about what types of spaces are essential versus desired and how this contributes to the principle of planning.

Discussion: Design Principles

When designing a small home several principles are key. First and most importantly, rooms must serve multiple purposes. Doing double duty means less space is needed for more activities. Our homes keep growing larger, in part because we want them to serve so many functions (Susanka, 2000, p.10). In small homes, adaptability is not something to forgo. Grouping parts of the home, such as the social parts conserves space. The kitchen, dining, and relaxing areas group well together, as do the private activities of sleeping and bathing. Moveable partitions are an easy way to keep options open with maximum flexibility (Wilhide, 2008, p. 24-25). Next, one must consider creating shelter around personal activity. Small pockets of space give someone a sense of comfort. This could mean a sheltered alcove that looks out into a larger space or a cozy hideaway for children. Another design principle addresses spatial volume; a variety of ceiling heights is actually the best way to create proportion and comfortable spaces. Contrary to popular belief, it is not the overall ceiling height that makes a space feel larger or more comfortable. A variation makes spaces feel individually defined (Susanka, 2000, p.11). A place to call your own is also especially important. Following current trends, houses are getting bigger because we have no place to get away. Creating a reflection space to be personal and enriched with meaningful items will help a person feel at home (Susanka, 2000, p.10).Making the most of natural lighting will increase the appeal of space. Light brings focus to form, accentuates color, and expresses texture. Form, color, and texture are great details when a space is small. Light also makes a space seem larger (Gauer, 2004, p.136; Wilhide, 2008, p.29-30). It is important to try and allow spaces to have multiple exposures; meaning light to enter from multiple directions. This is easier to achieve in smaller houses because often the main space can be given three exposures (Gauer, 2004, p.136-137). While these techniques work for larger homes, they are essential to small ones; they make or break the home.

Parameters of a Small Home

Building or selecting a small-scale house is one way that people chose to control their housing expenditure while simultaneously creating a meaningful fulfilling space. These houses are also called tiny homes and micro homes among followers of small scale living. Going smaller is about simplifying one’s life and utilizing every square inch to make it usable space. The idea of downsizing is focused on eliminating space, clutter, and reducing environmental impact. Downsizing into a small home usually means around 1,500 square feet or less. To be considered a tiny home, the dwelling must be under 875 square feet (Arvedlund, 2014). In large cities, many homes are in apartment or condo buildings. Both these types of structures as well as stand-alone homes both qualify as tiny homes.

Difficulties with Small Homes

Challenges such as building regulations and zoning laws can make or break the potential for small-scale living to be practical as well. In many cities, homes ranging from 600 to 700 square feet or less are prohibited. The idea of small homes can only progress so far when these regulations and laws stand in the way (Priesnitz, 2007, p.18-19). To foster innovation, several municipalities are waiving zoning regulations to allow construction of smaller dwellings. These test-runs are typically located at select sites and are trying to demonstrate that small-scale dwellings can adequately provide for occupant needs. These sites are in areas that governments are willing to experiment and collaborate with designers in hopes to find a successful solution. A handful of large cities such as Portland, Oregon, San Francisco, California, Chicago, Illinois, Boston, Massachusetts, Seattle, Washington, Washington, D.C. and Vancouver, Canada, are forerunners in change. These cities have permanently removed their regulations or are working on pilot projects to explore the outcomes of these models (Wong, 2013, p.46; Priesnitz, 2007, p.19; Priesntiz, 2014, p.14). If more cities are willing to lift regulations, more organizations will be willing to lend which will push this movement forward. Depending on the type of home, there may be regulations that must be followed. The laws can be highly restrictive, especially if the dwelling falls under 600 square feet (Priesnitz, 2007). Insurance policies and mortgages are another challenge for small-home owners. Currently, the industry of tiny homes is viewed as too risky by banks and insurance companies (Belge, 2014, p.72). Until a greater number of municipalities are backing this movement and provide education on the topic, expanding coverage and investment will continue to lag.

Current Design Changes

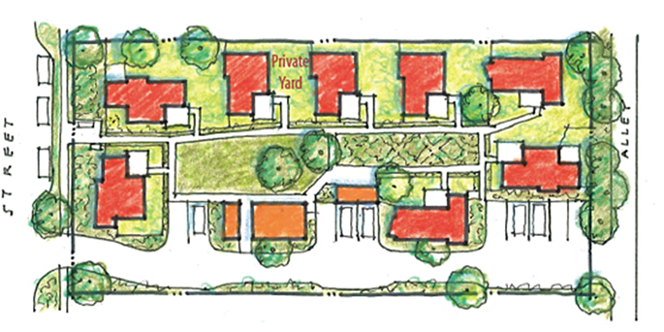

Pocket neighborhoods are also increasing in popularity. Ross Chapin (2011), author of Pocket Neighborhoods, is the father to the idea. According to him, a pocket neighborhood is “a cluster of compact but beautifully designed homes, usually located within an existing small town or a well-established first tier suburb.” They are designed for people instead of cars, meaning all houses face a centrally located commons space instead of the street. These neighborhoods encourage informal interactions, allowing people to get to know one another. These walkable friendly neighborhoods are not complete without a commons building. It is used as a gathering space to host dinners, meetings, games, and events (Chapin, 2011, p. 10-13). Images 6 and 7 depict possible neighborhood configurations.

Image 6: Pocket Neighborhood Configuration

Image 7: Pocket Neighborhood Configuration

The idea that “community matters” is at the root of the emerging tiny village philosophy. Pocket neighborhoods differ from regular neighborhoods by only allowing eight to twelve dwellings in a group. Neighbors often form strong relationships and are able to help each other out. This new trend allows a sense of community and caring to return (Priesnitz, 2014, p.14-18). Image 8 shows an existing experimental pocket neighborhood located in Port Townsend, Washington.

Image 8: Pocket Neighborhood in Washington

Other groups trying to make a difference are the tiny home manufacturers. Several select companies are selling floor plans or entire built structures in hopes to change lives. Some companies offer workshops for do-it-yourself homeowners and some resort to only offering space plans. Jay Shafer and his company Tumbleweed Tiny House Co. construct and design homes ranging from 65 to 774 square feet. This company is one of the most popular in the industry (Idlebrook, 2008, p. 56-57). When interviewed in a documentary, Shafer commented “Americans like their houses like they like their food, big and cheap” (Smith & Mueller, 2013). Shafer is a forerunner supporting this movement. He testifies with this own stories when describing his evolving home and lifestyle in the documentary Tiny: A story about living small by Christopher Smith and Merete Mueller (2013).

Discussion

How are home owners going to battle this issue of expanding homes? This paper proposes pocket neighborhoods could significantly reduce each personal home size and be a successful solution if they still satisfy these “wants”. As mentioned, pocket neighborhoods typically have a community building that provides the desired extra social spaces. If these bonus spaces are incorporated into the community center, people are more likely to accept living in a smaller home. With consumerism at an all-time high, we cannot expect the housing trend to decrease unless a viable solution is proposed. With a community building incorporating game rooms, exercise equipment, theater space, office space, and guest quarters, home builders can eliminate these privately owned spaces from all homes. Most of the time these are wasted space inside a single family home. If they become part of a shared space, not only does it save square footage, it fosters this ever dying sense of community.

Conclusion

A home is one of the most personal things one will ever have. An evaluation of your life and priorities is essential when moving into a small space. What are you willing to outsource? What must you have in your space? We must introspect on our personal lives, and leave others opinions of home out. Everyone’s meaning of home is different; therefore, everyone’s home shall be too.

In conclusion, there are multiple ways to begin simplifying our lives. The key to the small scale living avenue is so go smaller. That may mean living in 100 square feet or 1,000. In a time of overconsumption any bit helps. Many resources used in this research provide guides and insight for joining the movement. Whether a small apartment, mobile dwelling, or stationary home is appropriate, each one supports an ever growing nation in a positive manner. Designers have the opportunity to create a place that gives back on so many personal levels. Change can be daunting, but education for any innovative move helps influence users. Creating a positive attitude towards reasonable efficient living will help financially, spiritually, emotionally, and environmentally. When psychological connections and personal meaning merge with space efficient design and sustainable practices, small scale living will last into the future.

References

Annison, J. E. (2000). Towards a clearer understanding of the meaning of “home”. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 25 (4),251-262.

Arvedlund, E. (2014, August 17). Market for 'tiny' homes growing slowly. Philadelphia Inquirer.

Belge, K. (2014, July-August). Tiny houses, big hearts: Livin' large in a small abode. Curve, 24 (5), 72.

Bender, K. (2009, May-June). The new movement to seriously downsize our homes. E: The Environmental Magazine, 20 (3), 34-39.

Chapin, R. (2011). Pocket neighborhoods. Newtown, CT: The Taunton Press, Inc.

Despres, C. (1991). The meaning of home: Literature review and directions for future research and theoretical development. Journal of Architectural Planning and Research, 8, 96-115.

Easthope, H. (2004). A place called home. Housing, Theory, and Society, 21 (3),128-138.

Ferraro, C. (2009, Feb 21). Small but perfectly formed. Financial Times.

Fox, L. (2002). The meaning of home: A chimerical concept or a legal challenge?. Journal of Law and Society, 29 (4), 580-610.

Gauer, J. (2004). The new American dream: Living well in small homes. New York, NY: The Monacelli Press, Inc.

Grinberg, E. (2012, September 21). Tiny homes hit the big city. CNN Wire.

Idlebrook, C. (2008, October-November). Home petite home. Mother Earth News, 230, 56-58.

Kahn, L., & Welch, B. (2012, August-September). Cozy, affordable and inspiring tiny homes. Mother Earth News, 253, 40-45.

Mallett, S. (2004). Understanding home: A critical review of the literature. The Sociological Review, 52 (1), 62-89.

Marcus, C. C. (1995). House as a mirror of self: Exploring the deeper meaning of home. Berkeley, CA: Conari Press.

Priesnitz, W. (2007, May-June). Small is beautiful. Natural Life, 115, 18-21.

Priesnitz, W. (2014, March-April). Tiny houses, tiny neighborhoods. Natural Life, 12-19.

Sixsmith, J. (1986). The meaning of home: An exploratory study of environmental experience. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 6, 281-298.

Smith, C., & Mueller M. (Directors and Producers). (2013). Tiny: A story about living small [Motion Picture]. United States: Speak Thunder Films.

Smith, S. G. (1994). The essential qualities of a home. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 14, 31-46.

Susanka, S. (1998). The not so big house: A blueprint for the way we really live. Newtown, CT: The Taunton Press, Inc.

Susanka, S. (2000). Creating the not so big house: Insights and ideas for the new American home. Newtown, CT: The Taunton Press, Inc.

United States Census Bureau. (2013). [Graph Illustration of 2011 American Housing Survey]. Rooms, Size, and Amenities-All Housing Units (National). Retrieved from http://factfinder2.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=AHS_2011_C02AH&prodType=table

Wilhide, E. (2008). Small spaces: Maximizing limited spaces for living. London, England: Jacqui Small LLP.

Wong, V. (2013, March 18). Living small in the big city. Bloomberg Businessweek, 4321, 46-47.

Image References

Image 1: Retrieved from http://theskooloflife.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2009/05/maslows-hierarchy.gif

Image 2: Retrieved from http://www.houseplans.com/plan/98-square-feet-1-bedroom-1-bathroom-0-garage-cottage-38261

Image 3: Retrieved from http://www.houseplans.com/plan/1065-square-feet-2-bedrooms-2-bathroom-cottage-house-plans-0-garage-23511

Image 4: Retrieved from http://www.houseplans.com/plan/2320-square-feet-3-bedrooms-2-bathroom-craftsman-home-plans-2-garage-36650

Image 5: Retrieved from http://www.houseplans.com/plan/4032-square-feet-5-bedrooms-4-5-bathroom-modern-house-plan-2-garage-33117

Image 6: Retrieved from http://www.lifeedited.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/pocket-neighborhood-single-cluster.png

Image 7: Retrieved from http://www.shareable.net/sites/default/files/blog/top-image/clusters.jpg

Image 8: Retrieved from http://mediaassets.caller.com/photo/2014/05/11/20100205-165046-pic-745059233_4589945_ver1.0_640_480.jpg

Annotated Bibliography

Books (9)

Broto, C. (2004). Compact interiors. Barcelona, Spain: Links International.

Compact Interiors gives many examples of small scale living. Floor plans, sections, and oblique drawings provides the reader with a strong sense for the space. This book has more pictures than text.

Chapin, R. (2011). Pocket neighborhoods. Newtown, CT: The Taunton Press, Inc.

Ross Chapin describes his steps to discovering and creating pocket neighborhoods. These small quaint clusters of homes create a unique neighborhood feeling. These houses are appealing to those who long to have friendly relationships with neighbors, live on a smaller scale, share resources, but still have privacy. He explains how housing development like this works and how to create the same feeling in a place near you.

Conran, T. (2007). How to live in small spaces: Design, furnishing, decoration, detail for the smaller home. Buffalo, NY: Firefly Books Ltd.

Topics in this book include the design, planning, decorating, and furnishing small spaces. The book also touches on how to make the most of often unused spaces such as basements, attics, and sheds. As studies show, more people are willing to live in small locations for convenience. Spending less time on the road, being near attractions, and close to work are all important factors today’s professionals are considering. This means people are learning to make the best of lesser living space. The key to overcoming small spaces is to realize you are not being cheated if your home is not as spacious as you would have hoped. This book gives very specific ways to design small spaces.

Gauer, J. (2004). The new American dream: Living well in small homes. New York, NY: The Monacelli Press, Inc.

Ten principles from this book are the most important knowledge from this source. They relate directly to designing for small spaces. The ten principles are proportion, modularity, scale, transparency and spatial layering, hierarchy and procession, light, multi-functionalism, simplicity, economy, and modesty. These principles can apply to all spaces, but they are particularly influential in small spaces. Examples support all principles.

Jacobs, K. (2006). The perfect $100,000 house: A trip across America and back to in pursuit of a place to call home. New York, NY: Penguin Group USA, Inc.

This book is the story of Karrie Jacobs and her search for the perfect place to settle down. She travels the country in search of the right town, community, and home. She attends a two week house building camp and is tasked with designing a program for the house. Overall, this book is about her journey of learning to live with less and truly think about what home means.

Marcus, C. C. (1995). House as a mirror of self: Exploring the deeper meaning of home. Berkeley, CA: Conari Press.

Marcus describes the attachment to our homes and how each person can feel something different while being in their home. She defines the needs that a house fulfills, such as a place of self-expression, a refuge from society, and a root for memories. Previously, professionals that worked in the fields of architecture, anthropology, and geography have ignored the principle of emotional attachment. This along with many other characteristics described in this book help to explain what a home can mean to humans.

Susanka, S. (1998). The not so big house: A blueprint for the way we really live. Newtown, CT: The Taunton Press, Inc.

Susanka describes her journey discovering “starter castles” and deciding to build her Not So Big House with her architect husband. She shares the aspirations, struggles, needs, and realities of people who desire to change their way of living. The Not So Big House concept is focused on an informal lifestyle to fit today’s needs. It values quality over quantity and details over square footage.

Susanka, S. (2000). Creating the not so big house: Insights and ideas for the new American home. Newtown, CT: The Taunton Press, Inc.

This book focuses on broadening the range of a previous book by Sarah Susanka called “The Not So Big House.” People are longing for an alternative to bigger is better thinking, but they do not know how to create something functional, high quality, and space conscious. Twenty-five example homes are displayed from all over the United States. These case studies utilize Susanka’s key design concepts.

Susanka, S. (2002). Not so big solutions for your home. Newtown, CT: The Taunton Press, Inc.

The solutions presented in this book are answers to make a house a better place to live. This book is a manual for those who want to learn how to tailor their homes to fit their lifestyles. It is about solving the everyday problems average families face in their current homes. These solutions are easy to implement, but are not new or revolutionary.

Wilhide, E. (2008). Small spaces: Maximizing limited spaces for living. London, England: Jacqui Small LLP.

Elizabeth Wilhide looks at living in small spaces from a different perspective. While she agrees that they are more economical, she advocates that small space living concentrates the mind. When one has limited room, they must make wise choices and be selective. She vows that by using clever design strategies a user will experience better spatial quality. Adaptability is the key word to a successful small design.

Newspaper Articles (4)

Arvedlund, E. (2014, August 17). Market for 'tiny' homes growing slowly. Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved from http://articles.philly.com/2014-08-18/real_estate/52906036_1_tiny-house-large-house-the-small-house-book.

Qualifications and cost of tiny homes are discussed in this article. Tiny house builders and workshops tell about their offerings and how to tell if living this way of life is for you. A family gives their story on living in the typical American dream home and how it ruined their family dynamic. They have grown much closer as a family and grown into who they wanted to become by making the choice to hit the road in a tiny home.

Ferraro, C. (2009, Feb 21). Small but perfectly formed. Financial Times. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.er.lib.k-state.edu...

The small home trend is to go “smaller,” but some go under 500 square feet. They outsource what they do not have room for, such as laundry facilities and gym equipment. Double duty furniture is a lifesaver and technology is becoming smaller which fits nicely in a tiny house. This article talks about a free lifestyle with fewer worries. A lot of repetitive information in this article, therefore I will not use it in my paper.

Grinberg, E. (2012, September 21). Tiny homes hit the big city. CNN Wire. Retrieved from http://www.lexisnexis.com.er.lib.k-state.edu...

Living in a small home has its perks. The Berzins family describes what it is like to downsize. Hair Berzins describes the liberating feeling of being stress free. Mortgage free is becoming appealing to many buyers. It allows individuals to follow their dreams, volunteer, spend more time with family, and live debt free. New York is experimenting with micro-unit buildings in previously zoned areas. These design proposals consist of modular design units as well as sustainable design possibilities.

Trachtenberg, J. A. (2012, Jan 30). Tiny homes carve a niche; publishers crank out books on antidote to “Mcmansions”: Curiously small houses. Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.er.lib.k-state.edu....

This article lists other books that are coming on the market related to tiny homes. A couple books listed are Derek Diedricken’s “Humble Homes, Simple Shacks, Cozy Cottages, Ramshackle Retreats, Funky Forts,” and Richard Olsen’s “Handmade Houses: A Century of Earth-Friendly Home Design.”

Magazines (6)

Belge, K. (2014, July-August). Tiny houses, big hearts: Livin' large in a small abode. Curve, 24 (5), 72. Retrieved from http://go.galegroup.com/...

Two women, Jenn Kliese and Kim Langston, enjoy living in their new tiny homes in Olympia, Washington. They took home design classes and workshops to design their new homes. They speak on downsizing and its difficulties parting with old memories. Kliese explains her monthly expenses. Challenges such as banks not loaning money and insurance companies not offering policies on such houses are obstacles every tiny homeowner must face.

Bender, K. (2009, May-June). The new movement to seriously downsize our homes. E: The Environmental Magazine, 20 (3), 34-39. Retrieved from http://go.galegroup.com.er.lib.k-state.edu...

This article talks statistics pertaining to the growing square footage of American homes. The Small House Society is an organization, founded in 2002, that consists of 40 architects and urban planners who have built over 500 tiny homes. The Olive 8 project is introduced as a development of 229 condos atop a hotel in Seattle, Washington. This article talks about the negative connotations surrounding small houses.

Idlebrook, C. (2008, October-November). Home petite home. Mother Earth News, 230, 56-58. Retrieved from http://tinyhouseblog.com/tiny-house/home-petite-home/.

Living small is about choosing quality over quantity. The housing market in America is super-sized and people battle for square footage. This article is the story of a family creating a comfortable home in Maine. They give space saving tips and double duty design. They talk of their future expansion plans to welcome a new baby. The Speed family gives a firsthand example of how to live in a small house with a family.

Kahn, L., & Welch, B. (2012, August-September). Cozy, affordable and inspiring tiny homes. Mother Earth News, 253, 40-45. Retrieved from file:///C:/Users/Shelby %20Kiser/Downloads/ProQuestDocuments-2015-06-27.html

Focusing on a concept that began in the 1960’s, this article captures a man’s perspective on hand built homes. Lloyd Kahn speaks about overconsumption and people currently living beyond their means. Young people are beginning to pick up the trend of minimum-sized housing. A handful of tiny houses are shown as examples. There is advice on starting ones small home.

Priesnitz, W. (2007, May-June). Small is beautiful. Natural Life, 115, 18-21. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.er.lib.k-state.edu...

America is the exception to the rule. In most other countries, micro living spaces are the norm. Extended families tend to stay together and share resources. Trends such as early retirement, switching careers, and interests in traveling are playing a role in “right-sizing.” This concept is about living in the space we need instead of what we think we need to keep up with the Jones’. The simplest way to cut energy costs is to downsize. Renovating existing homes built between 1945 and 1975 are an alternative to building new.

Priesnitz, W. (2014, March-April). Tiny houses, tiny neighborhoods. Natural Life, 12-19. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.er.lib.k-state.edu...

Tiny neighborhoods are pods of small homes that face courtyards and shared community spaces. These new areas focus on neighbor relationships, safety, privacy, and efficiency. This article talks about the zoning laws and building codes and the ways to get around them. The difference between subdivision neighborhoods and pocket neighborhoods is discussed. Ross Chapin the founder of pocket neighborhoods describes the advantages and importance of design to foster communication and collaboration between houses.

Newsletters (1)

Wong, V. (2013, March 18). Living small in the big city. Bloomberg Businessweek, 4321, 46-47. Retrieved from http://web.b.ebscohost.com.er.lib.k-state.edu...

Micro-apartments are setting a trend in many big cities. Urban planners experiment with small scale housing to meet the needs of young professionals, students, and elderly. The goals of these apartments are to keep rent costs lower and be more efficient. They are calling this trend “Europeanization.” Architects are also designing residences with group studios and communal areas for more space to cook, dine, and be active.

Journal Articles (4)

Annison, J. E. (2000). Towards a clearer understanding of the meaning of “home”. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 25 (4),251-262. Retrieved from http://web.a.ebscohost.com.er.lib.k-state.edu...

A home is a multi-faceted concept with many attributes to make it a home and many factors that contribute to a non-home feeling as well. This article analyses J. O’Brien, J. Sixsmith, C. Despres, and S. Smith’s work regarding the meaning of home and the categories that make one feel a sense of belonging, ownership, and peace. There are multiple modes that make a complete home, such as the personal home, the social home, and the physical home. Each reflects different experiences and notions that come from a certain piece. Another way of evaluating home is using Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. In this perspective, a home first provides physiological and safety needs before it can satisfy self-esteem and social needs. This article covers several views on what a home means and how to understand what contributes to that feeling.

Easthope, H. (2004). A place called home. Housing, Theory, and Society, 21 (3),128-138. Retrieved from http://web.a.ebscohost.com.er.lib.k-state.edu...

In a time of increasing migration, expanding urbanization, and growing investments in construction, the importance of the concept of place for housing researchers is on the forefront. Understanding home as a significant type of place provides insight into people’s identities and psychological well-being. It is important to look beyond the scale of individual households to the regional, national, and international scale. Dwelling, which we may refer to as house, is the capacity to achieve a spiritual unity between humans and things. It is crucial to not adopt a rigid definition of home because each person experiences and understands home differently depending on context, background, and culture.

Fox, L. (2002). The meaning of home: A chimerical concept or a legal challenge?. Journal of Law and Society, 29 (4), 580-610. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.er.lib.k-state.edu...

A portion of this article is dedicated to understanding home for a legal definition, but the main information supports the meaning of home from a broad perspective. It is much easier to understand and relate to a physical structure, but when it comes to emotions, it gets messy. The abstract feelings make it hard to pinpoint a universal meaning. The feelings about home can be grouped into four categories; home as a physical structure, home as a territory, home as a center for self-identity, and home as a social and cultural unit. It begins with the actual structure that provides shelter for its occupiers. This part enables the other attributes of home to be experienced. Research regarding the home has been around for decades, but recent studies show that it is the association with family that gives the contemporary home cultural identity.

Mallett, S. (2004). Understanding home: A critical review of the literature. The Sociological Review, 52 (1), 62-89. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com.er.lib.k-state.edu...

Is home a place, space, feeling, practice, or a state of being? Home may mean all of these in one context or another. Typically, home means the place where one lives, a house or other dwelling, or a person’s country or city. The research on home spans from many disciplines, such as sociology, anthropology, psychology, geography, history, architecture, and philosophy. In English, the word “home” derives from the Anglo-Saxon word “ham,” meaning village, estate, or town. In most countries, home ownership is applauded and is a symbol of social status. In the case of the United States, deceptive marketing strategies are used to convince people that bigger and newer is better. By understanding the true meaning of home, we better grasp that home is more about psychology than physicality.

Illustrations (1)

United States Census Bureau. (2013). [Graph Illustration of 2011 American Housing Survey]. Rooms, Size, and Amenities-All Housing Units (National). Retrieved from http://factfinder2.census.gov...

This graph organizes data from a housing survey of the United States. There is information on the number of total rooms, bedrooms, and bathrooms in each house. Square footage is measured and recorded in 500 square foot increments. These are all houses including vacant, rental, and owned.

Documentary (1)

Smith, C., & Mueller M. (Directors and Producers). (2013). Tiny: A story about living small [Motion Picture]. United States: Speak Thunder Films.

A movie written by two young adults building a tiny home. They had no construction experience and a limited budget. This is their story about downsizing, challenges of building, and the connection to nature. Throughout the movie, other tiny home owners spoke about their lifestyle. Many gave tours of their homes. A key role model, Jay Shafer, owner of Tumbleweed Tiny House Co. told his story about the beginning of the movement. He talked about the current housing trends and what his company offers. Overall, this documentary added another dimension to the research by showing examples, the real struggles of downsizing, and the emotional journey this couple took.