An Empirical Evidence of Breast Cancer in our Daily Food Consumption

Gautham

Vaidyanathan

Penn High School, Mishawaka, Indiana

ABSTRACT

The World Health Organization recently reported that breast cancer has become the most common cancer in women throughout the world. This paper explores the relationship between Gross Domestic Product, fruits, and vegetables consumption over meat consumption, and breast cancer occurrences in populations in the developed and developing countries. To investigate this hypothesis, data were collected from various Internet sources for a snapshot of time period. Empirical analyses comparing developed and developing countries show increased breast cancers incidence in developed countries. The ratio of vegetables and fruits consumption over meat consumption was found to have independent, statistically significant association with breast cancer risk. This study explores how dietary habits and the comparison of vegetables and fruits consumption over meat consumption as well as the affluence of a country play a role in the etiology of breast cancer. The analysis of comparative consumption of vegetables and fruits over meat is the main contribution of this study towards cancer research.

Introduction

Breast cancer is the leading cancer in women, both in the developed and the developing world. More than one million incidences of breast cancer cases were identified in 2000 (Globocan, 2000). Cancer has been linked to exposure to certain chemicals, biological agents such as certain viruses, physical agents such as radiation, and more recently to dietary habits. Preventive action to substantially reduce or eliminate these toxic exposures will reduce the burden of cancer and other diseases. This study focuses on the dietary input of humans and how these diets impact breast cancer rates.According to recent estimates, up to 40% of human cancers may be related to diet (Ferguson, 1999; Doll, Peto, 1981). It is believed that a diet high in fat and low in fiber increases cancer risk. Less studied are dietary exposures to potential carcinogens present in the U.S. food supply. These include chemicals such as DDT, dioxins, and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), and trace metals such as arsenic. A recent survey detected the DDT in 20% of solid foods sample (MacIntosh et al., 2001). Fish consumption accounts for much of our dietary exposure to pesticides and dioxins (Schecter et al., 2001; Dougherty et al., 2000). PCBs have been detected in fish (Humphrey, Gardiner, Pandya, et al., 2000). The presence of these carcinogens in our food supply raises significant concerns.

Research on vegetables and fruit diet and cancer has produced dichotomous results. American Institute for Cancer Research (1997) reported inverse associations between intakes of fruits or vegetables and incidence of various cancers in a study. In another report no relation was observed between total fruit and vegetable consumption and overall cancer incidence (Hung, Joshipura, Jiang, et al., 2004). In a study in Germany, Adzerson, Jess, Freivogel, et al., (2003) found that components of raw vegetables and their micronutrients appear to decrease breast cancer risk. A study by The Alpha-Tocopherol Beta-Carotene Cancer Prevention Study Group (1994) even suggested harm in the intake of high doses of single constituents of fruits and vegetables, and beta-carotene in particular.

The research on meat consumption and cancer has produced conflicting results as well. Of the correlations between dietary factors and various cancers, the relationship between meat consumption and colon cancer has been the strongest (van Gils, et al., 2005). A fact sheet prepared by Warren and Devine (2000) suggests that there is a possible relationship between eating meat, especially beef and cured meats, and an increase in the risk of breast cancer. Another study suggests that although no association was observed between meat consumption and breast cancer risk, it was unable to assess the effect of cooking method or the level to which meat is cooked, as the majority of studies did not collect this information (Missmer et al., 2002). For instance, meat cooked at high temperatures (e.g., frying and barbecuing) and well-done meat (especially to the point of charring) contains heterocyclic amines, known to be carcinogenic (National Cancer Institute, 2004).

As discussed above, studies have not concluded significant relationships between cancer rates and food consumption in general. This study uses published data from various sources to hypothesize the relationship between breast cancer occurrence rates and the consumption of vegetables, fruits, and meat in developed and less-developed countries. The next section discusses various nutrients that have been hypothesized in prior research to reduce cancer rates. The third section introduces the hypotheses proposed in this study followed by the results of statistical analysis and discussion. The final section illustrates limitations of this study and future research direction.

Nutrients and breast cancer

The strongest evidence of a relationship between diet and cancer has been related to the benefit of consumption of least five servings of fruits and vegetables per day (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2005). Most of the research has focused on the effects of specific agents contained in fruits and vegetables such as carotenoids, selenium, folic acid, fiber, and Vitamins C and E. A study (Steinmetz, 1991) suggests that fruits and vegetables contain an anti-carcinogenic cocktail of substances, including both recognized nutrients and non-nutritive constituents. Together they inhibit the formation of carcinogens, reduce the capacity of transformed cells to proliferate, and act as antioxidants.In studies, green vegetables and cruciferous vegetables seemed beneficial. However, the prospective cohort studies to examine this relationship have yielded less conclusive findings (Voorips, et al., 2000). Vegetables contain so many beneficial vitamins and nutrients that it is difficult to identify which ones might be responsible for the possible association with colon cancer. Fiber, minerals, and vitamins have been examined in many studies and have the potential to either decrease or deter cancer occurrence rates.

Fiber, Vitamins, and Minerals

Fiber, the structural part of plants that is indigestible by humans, is an element that can be found in grains, legumes, and fruits. It is made up of the material composing the walls of the cells of whole grains, fruits, and vegetables. Fiber component of fruit and vegetables has been connected with decreased risk of breast cancer (Warren, Devine, 2000). Fiber may reduce levels of estrogens by increasing their elimination in bile. Bile is produced by the liver and emptied into the small intestine. It aids in digestion and also functions as a pathway for the elimination of various chemicals, such as the estrogens. Fiber in the intestines can bind to the estrogens in the bile and ensure their elimination. Fiber can also decrease the type of bacteria in the intestine that lead to re-absorption of estrogens from the bile into the body. Antioxidant minerals and vitamins decrease cancer risk by preventing tissue damage by trapping organic free radicals and/or deactivating excited oxygen molecules, a by-product of many metabolic functions (Hemmekens, 1994).An analysis based on a uniquely large series of micronutrients confirm that vitamin C, vitamin E, and selected carotenoids are inversely related to breast-cancer risk, possibly through antioxidant mechanisms, with risk estimates which were, if anything, higher than the pooled estimates provided by a meta-analysis of other published studies (Gandini, Merzenich, Robertson, Boyle, et al., 2000). Among various carotenoids considered, a study showed an inverse association with a-carotene, b-carotene, lutein, and xeazanthin (Freudenheim, et al., 1996; La Vecchia, et al., 1998). The studies also provided further and convincing evidence that retinol is unrelated to breast-cancer risk, indicating that any protective role of carotenoids is unlikely to be related to their vitamin A-related activity. In humans, carotenoids play two primary roles: some are converted into vitamin A and others exert antioxidant activity. The carotenoids that the body is able to convert to vitamin A are referred to as "provitamin A" carotenoids, for example beta-carotene and alpha-carotene. Some of the better-known carotenoids without "provitamin A" activity-but with very high antioxidant activity-are lutein, lycopene, and zeaxanthin. After multivariate analysis, a significant association was evident also for vitamin E, another anti-oxidant vitamin (Zhang, et al., 1999).

Calcium and vitamin D may be associated with enhanced survival rates among breast cancer cases (Garland, Garland, Corham, 1999). Diet rich in several micronutrients, particularly beta-carotene, vitamin E, and calcium, may be protective against breast cancer (Negri, et al., 1996). Low dietary intake of selenium has been proposed as a risk factor for breast cancer (Hunter, et al., 1990). Potassium ion (K+) channels are known to play a key role in breast cancer proliferation (Abdul, Santo, Hoosein, 2003). Table 1 lists the nutrient content of some of the fruits and vegetables that possesses the various nutrients in the above-mentioned studies.

Fruit/Vegetable Fiber Minerals Vitamins Apple 4 grams Calcium, Selenium Vitamin A , C, E Avocado (medium) 10 grams Potassium, Calcium, Selenium Vitamin A, C Banana (medium) 3 grams Potassium, Calcium, Selenium Vitamin A , C, E Blackberry (1 cup) 7 grams Potassium, Calcium, Selenium Vitamin A, C, E , Lutein, Lycopene, and Zeaxanthin Cantaloupe (medium) 0.55 grams Potassium, Calcium Vitamin A, C, b-carotene Grapes (1 cup) 1.6 grams Potassium, Calcium, Selenium Vitamin A, C Mango (medium) 3 grams Potassium, Calcium, Selenium Vitamin A , C, E, b-carotene Lemon (peeled) 1.6 grams Potassium, Calcium Vitamin A , C Strawberry (1 cup) 3 grams Calcium, Selenium Vitamin A, C, Lutein, Lycopene, and Zeaxanthin Tomato (medium) 1.35 grams Potassium, Calcium, Selenium Vitamin A, C, a-carotene, Lutein, Lycopene, Zeaxanthin Orange (medium) 3 grams Potassium, Calcium, Selenium Vitamin A, C Broccoli (� cup cooked) 2.3 grams Potassium, Calcium, Selenium Vitamin A, C, b-carotene Carrot (� cup cooked) 2.6 grams Potassium, Calcium, Selenium Vitamin A, C, a-carotene and b-carotene Corn (� cup cooked) 2.1 grams Potassium, Calcium, Selenium Vitamin A, Vitamin C Cucumber (� cup ) 0.42 grams Potassium, Calcium, Selenium Vitamin A, Vitamin C Green Pepper (small) 1.3 grams Potassium, Calcium, Selenium Vitamin A, Vitamin C Mushroom (� cup) 0 .42 grams Potassium, Calcium, Selenium Vitamin C - .8 mg Onions (small cooked) 1.3 grams Potassium, Calcium, Selenium Vitamin C Peas (1 cup boiled) 8.8 grams Potassium, Calcium, Selenium Vitamin A, Vitamin C Baked Potato (medium) 2.3 grams Potassium, Calcium, Selenium Vitamin C Spinach (1 cup) 0 .81 grams Potassium, Calcium, Selenium Vitamin A , C, b-carotene Baked Squash (1 cup) 2.5 grams Potassium, Calcium, Selenium Vitamin A , C, b-carotene

Using the above-mentioned nutrient values of vegetables and fruits in dietary consumption, the next section proposes a research model.

Research

Model

The World Health Organization recently reported that breast cancer has

become the most common cancer in women throughout the world. As discussed

in the above sections, there is a dichotomous view of how vegetables,

fruits, and meat consumption affect cancer occurrences. The data sample

for this research was drawn from various data sources. Data from Globocan

2000, United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization, United Nations

and World factors website, and Human Development Reports were used. Sample

data were collected for 52 countries from the 150 developed and less developed

countries. Some of the countries were dropped because complete data were

not available. The cancer incidence rates were drawn from GLOBOCAN 2000

database. The population facts of countries were collected from the United

Nations and World Factors and Figures website. The food consumption was

drawn from the food balance sheet database from the United Nations Food

and Agricultural Organization. All data have been taken as an average

between the years 2000 and 2001. The data were collated and analyzed on

developing and developed countries so that statistical analyses could

be performed with similar definitions across other studies.

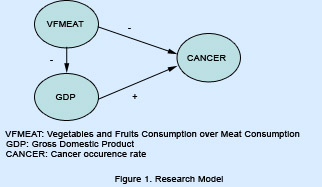

This study views this issue from a totally different angle. It focuses on the role played by vegetables and fruits consumption over meat consumption on cancer as well as how the affluence of a country plays a role in the consumption of fruits and vegetables over meat consumption. The vegetable and fruit consumption was compared to the meat consumption in various countries. Figure 1 illustrates the proposed research model.

Cancer

and Vegetables, Fruits, and Meat Consumption

Consumption of vegetables and fruits as well as consumption of meat has

been studied with respect to breast cancer risks. Studies have illustrated

dichotomous views of breast cancer risk (Adzerson, et al. 2003; Hung,

et al., 2004; Warren, Devine, 2000; Missmer, et al., 2002). However, case

control studies of diet where patients with cancer and a control group

are asked about their diet years in the past can be misleading as those

who participate are likely to be more health conscious and therefore consume

more fruits and vegetables and less fat than those who do not (Willett,

2005). Based on various kinds of study, there is a broad agreement today

that dietary factors may play an important role in carcinogenic processes

(Hursting, et al., 1999) but there is a methodological weakness when evaluating

such impacts (Hjartaker, 2003). In this study, a different methodology

is adopted. A ratio of consumption of vegetables and fruits and consumption

of meat per population was calculated and used as an independent variable.

To determine the cancer effects of vegetables/fruits to meat consumption,

the dependent variable was computed as cancer incidence rates, i.e., the

number of cancer incidences per population in various countries. Using

this independent variable, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1. The effect of vegetable and fruit consumption over meat consumption is negatively associated with cancer incidence rates.

Affluence,

diet and breast cancer

Developed countries (DC) according the definition from the United Nations

webpage are countries that generally have a per capita Gross Domestic

Product (GDP) in excess of $10,000. Less developed counties (LDC) are

mainly countries and dependent areas with low levels of output, living

standards, and technology; per capita GDPs are generally below $5,000

and often less than $1,500.  However,

the group also includes a number of countries with high per capita incomes,

areas of advanced technology, and rapid rates of growth. This includes

advanced developing countries, developing countries, Four Dragons (Four

Tigers), and newly industrializing economies. To understand the effects

on the developed and less developed counties, we use the variable GDP.

Even though the food consumption patterns are different in these countries,

there is a difference in the purchasing power of these countries. Since

meat is more expensive than vegetables and fruits, developed countries

generally have more access to meat and may therefore consume more meat

than less developed countries. Moreover, the consumption of meat may be

more than the consumption of vegetables and fruits. Since much of the

research that we have identified in this study concerns the effects of

vegetables and fruits on colorectal cancer, we hypothesize the following:

However,

the group also includes a number of countries with high per capita incomes,

areas of advanced technology, and rapid rates of growth. This includes

advanced developing countries, developing countries, Four Dragons (Four

Tigers), and newly industrializing economies. To understand the effects

on the developed and less developed counties, we use the variable GDP.

Even though the food consumption patterns are different in these countries,

there is a difference in the purchasing power of these countries. Since

meat is more expensive than vegetables and fruits, developed countries

generally have more access to meat and may therefore consume more meat

than less developed countries. Moreover, the consumption of meat may be

more than the consumption of vegetables and fruits. Since much of the

research that we have identified in this study concerns the effects of

vegetables and fruits on colorectal cancer, we hypothesize the following:

H2. The effect of cancer incidence rates is positively associated with the affluence of a country.

H3. More vegetables and fruits consumption than meat consumption is negatively associated with affluence of a country.

Results

Preliminary steps were taken in order to assure that a linear regression

test could be conducted. A scatter plot and residual plot were observed.

The scatter plot for the first hypothesis tested, where cancer incidence

rates was the dependent variable and GDP was the independent variable,

had a correlation value of 0.864. Although the data do have some outliers,

the 0.846 correlation shows that the linear relationship between the two

variables is positive and very strong. The scatter plot between the cancer

incidence rates and vegetable fruit to meat consumption ratio variable

shows a strong, negative correlation value of -0.658. All of this supports

a linear regression test being conducted.

After the linear tests were conducted, the results for the first test comparing cancer incidence rate and GDP showed an R2 value of 0.754 and a p-value of 0.00016. The R2 value is high simply stating that 75.4% of the variation in cancer incidence rate is explained by the regression. For this experiment, an alpha level of 0.05 was chosen, and the p value of 0.00016 is less than that alpha level. Because it is smaller than the noted significance level, the p-value is significant. This means that such an extreme value for what was tested cannot occur due to chance alone. Descriptive analyses comparing developed and lesser-developed countries show increased breast cancers incidence in developed countries. These results suggest an inverse association between breast cancer and vegetables/fruits over meat consumption.

The means, standard deviations, and correlations are reported in Table 2. The p-values are less than the standard 0.05 value, and so there is enough evidence to accept our hypotheses. This study finds a positive association between cancer incidence rates and the GDP of a country and a negative association between vegetables/fruits consumption over meat consumption and cancer incidence rates. The Durbin-Watson value of 2.2 tells us that there is no serial correlation. Therefore, this study concludes that the developed countries have a higher rate of breast cancer, and that as the ratio between vegetables/fruits consumption over meat consumption increases, the cancer rate in a population decreases. The results as shown in Table 2 illustrates that more vegetables and fruits consumption than meat consumption is negatively associated with affluence of a country.

Conclusion

and limitations of the study

Global patterns of breast cancer disparities support the association between

affluence, meat consumption, and the development of breast cancer. The

vegetables/fruits consumption over meat consumption factor is found to

have independent, statistically significant inverse associations with

breast cancer risk. We conclude that total GDP and meat consumption may

play an important role in breast cancer risk. How does meat consumption

increase the risk? The reason could be that fat in meat cells produce

estrogen, which may stimulate breast cancer cells. Therefore, the amount

of fat consumption can increase the amount of estrogen produced by your

body, thus feeding the cancer cells. However, before this association

can be considered causal we need confirmatory data from further studies

and a better understanding of possible biologic mechanisms that trigger

breast cancer. The low caloric diet in less developed countries probably

prevents the growth of tumors. There is an advantage to this hunger. Breast

cancer is probably a disease of modern life.

Breast cancer is an extremely complex disease and it is difficult to research the impact of specific dietary factors on breast cancer risk. Limitations of the data include differences in the accuracy of census figures, diagnostic accuracy, and coding practices among nations. Under-registration of cancer in some populations may exaggerate the range of variation. Although there is a close correlation between GDP, meat consumption, and the incidence rate of breast cancer, meat consumption could be a surrogate marker for other aspects of more affluent lifestyles. The true effect of GDP and dietary lifestyle on breast cancer risk might not have been detectable because of the relatively small data set and lack of longitudinal study. In view of the major potential public health consequence of these results, further studies of GDP and plant based diet to breast cancer connection are required. The role of estrogen in breast cancer risk has raised the possibility that environmental contaminants that mimic estrogen might also be involved. Detrimental effects of modernity, affluence, and their associated lifestyles and socio-demographics must also be examined in depth for their contribution to disproportionate rates of breast cancer worldwide.

References

Abdul, M., A. Santo, N. Hoosein. 2003. Activity of potassium channel-blockers

in breast cancer. Anticancer Research, 23(4):3347-51.

Adzerson, K., P. Jess, W. Freivogel, et al. 2003. Raw and cooked vegetables,

fruits, selected micronutrients, and breast cancer risk: A case-control

study in Germany. Nutrition and Cancer, 46(2): 131-137.

The Alpha-Tocopherol Beta-Carotene Cancer Prevention Study Group. 1994.

The effect of vitamin E and beta carotene on the incidence of lung cancer

and other cancers in male smokers. New England Journal of Medicine,

330:1029-1035.

American Institute for Cancer Research. 1997. Food, Nutrition and the

Prevention of Cancer: A Global Perspective. World Cancer Research Fund,

Washington, DC: American Institute for Cancer Research.

Doll, R., R. Peto, R. 1981. The causes of cancer: Quantitative estimates

of avoidable risks of cancer in the United States today. Journal of

National Cancer Institute, 66: 1191-1308.

Dougherty C.P., et al. 2000. Dietary exposures to food contaminants across

the United States. Environmental Research, 84:170-185.

Ferguson, L. R. 1999. Natural and man-made mutagens and carcinogens in

the human diet. Mutation Research, 443:1-10.

Freudenheim J.L, et al. 1996. Premenopausal breast cancer risk and intake

of vegetables, fruits, and related nutrients. Journal of National Cancer

Institute, 88:340-348.

Gandini, S., H. Merzenich, C. Robertson, P. Boyle. 2000. Meta-analysis

of studies on breast cancer risk and diet: the role of fruit and vegetable

consumption and the intake of associated micronutrients. European Journal

of Cancer, 36:636-646.

Garland, C.F., F.C. Garland, F.C., Gorham, E.D. 1999. Calcium and Vitamin

D: Their Potential Roles in Colon and Breast Cancer Prevention. Annals

of the New York Academy of Sciences, 889:107-119.

Globocan, 2000. http://www-dep.iarc.fr/globocan/database.htm

Hemmekens, C.H. 1994. Antioxidant vitamins and cancer. American Journal

of Medicine, 97(3A): 2S-4S.

Hjartaker, A. 2003. Fish consumption and risk of breast, colorectal and

prostate cancer: a critical evaluation of epidemiological studies. Scandinavian

Journal of Nutrition, 47(3): 111-122.

Humphrey, H., J.C. Gardiner, J.R. Pandya, et al. 2000. PCB Congener Profile

in the Serum of Humans Consuming Great Lakes Fish. Environmental Health

Perspectives, 108(2):167-172.

Hung H.C., K.J. Joshipura, R. Jiang. 2004. Fruit and vegetable intake

and risk of major chronic disease. Journal of National Cancer Institute,

96:1577-1584.

Hunter, D.J., et al. 1990. A prospective study of selenium status and

breast cancer risk. Journal of American Medical Association, 264(9):1128-31.

Hursting, S.D., et al. 1999. Mechanism-Based Cancer Prevention Approaches:

Targets, Examples, and the Use of Transgenic Mice. Journal of the National

Cancer Institute, 91(3). http://www.nal.usda.gov/fnic/ for nutrient

contents of fruits, nuts and vegetables

La Vecchia, C., M. Ferraroni, E. Negri, S. Franceschi. 1998. Role of carotenoids

in the risk of breast cancer. Journal of National Cancer Institute,

75:482- 483.

MacIntosh D.L., et al. 2001. Longitudinal investigation of dietary exposure

to selected pesticides. Environmental Health Perspectives, 109:145-150.

Missmer, S.A., et al. 2002. Meat and dairy food consumption and breast

cancer: a pooled analysis of cohort studies. International Journal

of Epidemiology, 31: 78-85.

National Cancer Institute. 2004. Heterocyclic amines in cooked meats.

Cancer Facts, http:// cis.nci.nih.gov/fact/3-25.htm

Negri, E. et al. 1996. Intake of selected micronutrients and the risk

of breast cancer. Journal of National Cancer Institute, 65:140-144.

Schecter A., et al. 2001. Intake of dioxins and related compounds from

food in the US population. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental

Health, 63:101-118.

Steinmetz, K.A. J.D. Potter. 1991. Vegetables, fruit and cancer. Cancer

Causes Control, 2(6):427-442.

U.S. Department of Agriculture 2005. Dietary guidelines for Americans.

Center for nutrition and Promotion. http://www.health.gov/dietaryguidelines/dga2005/document/pdf/

DGA2005.pdf

van Gils, et al. 2005. Consumption of Vegetables and Fruits and Risk of

Breast Cancer. Journal of American Medical Association, 293: 183-193.

Voorrips, L.E. et al. 2000. Vegetable and fruit consumption and risks

of colon and rectal cancer in a prospective cohort study: The Netherlands

Cohort Study on Diet and Cancer, American Journal of Epidemiology,

152(11): 1081-1092.

Warren, B.S., Devine, C. 2000. Meat, Poultry and Fish and the Risk of

Breast Cancer. Cornell University Program on Breast Cancer and Environmental

Risk Factors in New York State (BCERF), Fact Sheet 39.

Willett, W.C. 2005. Diet and Cancer: An evolving picture. The Journal

of American Medical Association, 293(2) 233-237.

Zhang S, et al. 1999. Dietary carotenoids and vitamins A, C, and E and

risk of breast cancer. Journal of National Cancer Institute, 91:547.

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations Breast Cancer incidence rate (1) Vegetable and Fruits to Meat Consumption (2) GDP/per capita (3) ** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed)

|