Effects of Family Mealtime Practices on Household Inhabitants

Lindsay

A. Schwarz

Eastern Illinois University

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this study was to determine how various family mealtime practices influence family dynamics. The objectives were to determine the frequency of meals per week consumed as a family, which meal was typically consumed together, influencing factors on why families do or do not choose to eat together, and the extent to which the participants perceived that family meal time strengthens the family unit. Participants (n=50) in the study completed a self-administered survey that consisted of questions regarding current family mealtime practices, as well as general questions about the family unit. Results indicated that family meals have the potential to contribute positively to the family unit. Further research comparing family characteristics of those who do consume family meals to those who don't is warranted.

Introduction

Few studies have examined the associations between family meal patterns and the health and well being of household members. Little is known about how the family unit is strengthened as a result of an increase in family meals. Current research indicates that the family meal has undergone changes over the years that have led to negative effects on the eating habits, food choices, family ties, and the sociability and adjustment of adolescents. Far too many families use activities as the excuse for not being together, rather than seeing it as a choice of priorities they've made (Whitaker, Deeks, Baughcum, & Specker, 2001). Family meals allow for interaction and healthy nutrition. This research has expanded upon the limited research examining family meal patterns and associations with the health, well-being, and dietary intake of the family.The Family Unit

People's lives are shaped in different ways according to their parents' models and expectations of what development should be (Foster, 2001). The family is referred to as one or two parents and their responsibility for the growth and development of one or more children. The family is responsible for the socialization and values of children. The amount of time spent together and the way in which it is spent is a determinant of the closeness of the family unit (Neumark-Stainer, Hannan, Story, Croll, & Perry, 2003). Healthy families value table time and conversation at family meals. Therapists say that there is a relationship between the love in a home and the richness of the family table (Foster, 2001).Definition of the Family Meal

The family meal has the potential for providing youth with opportunities for positive interactions with other family members, as well as for contributing to good nutritional health (Curran, 2003). The United States Food and Drug Administration defines a meal as a portion of a pyramid-based dietary intake that includes three to five food groups (Renkyl, 2000). A family meal is more than a source of nutrition; family meals have been shown to promote family connectedness, development of healthful eating behaviors, and the consumption of a healthful diet. The family is more specifically defined as "Any configuration of people who regularly eat together, or from the same household food resources, and who mutually influence decisions about food." (Gillespie & Gillespie, 2000, p. 1). A meal is considered a facilitator of food intake (Meiselman, 2000) as well as a planned social interaction that focuses on food. Family meals help children learn to distinguish between edible versus inedible food, how to prepare foods, and how to behave in a family meal setting (Meiselman, 2000). Despite this significance, many families experience obstacles to consuming meals together.Influencing Factors on the Frequency of Family Meals

Research on young children and teens now supports the value of the family meal as a tool parents can use to help them raise healthy children. However, eating together as a family presents a challenge for many adolescents and their families as they cope with school demands, work schedules, and extracurricular activities (Renkyl, 2000). Researchers Neumark-Sztainer, Story, Ackard, Moe, Perry (2000) found that although 74% of adolescents (n=4,629) indicated that they enjoyed eating meals with their families, 53% reported that different schedules don't let them eat meals together on a regular basis. There are also findings that indicate changes in family meal patterns over time and differences in family meals by sociodemographic characteristics. In one particular study of 15,202 adolescents, 14.0% reported eating family meals never, 19.1% reported one to two times per week, 21.5% reported three or four times per week, 18.9% reported five or six times per week, 18% reported seven times per week, and 18% reported eating meals as a family more than seven times per week (Escobar, 1999).When frequency of family meals is compared across sociodemographic characteristics, girls tend to report fewer family meals than boys. Frequency of family meals was significantly higher among middle school students than among high school students (Smolak & Levine, 1995). Studies suggest significant racial differences in family meal patterns, with the highest frequency reported by Asian Americans. The mean frequency of family meals is highest in many studies among youths whose mothers work full time. Overall literature shows that frequent meals consumed together as a family are far from the norm. American families eat dinner together less than half the time, and the meals usually last less than twenty minutes (Fiese, Tomcho, Douglas, Josephs, Poltrock, & Baker, 2002).

Impact of Family Meal on the Strength of the Family Unit

According to a national survey of more than 1,000 married men and women across the country, the daily ritual of gathering together at the dinner table is considered the most important way to strengthen family ties (Cox, 2002). Despite the stressful, fast-paced nature of present life, a family that makes time for meals together has better connections with each other. With everyone going their separate ways during the day, dinner can be the only time for the whole family to be together. Although it may not be convenient, parents should make a family dinner a priority. Being together as a family can make a difference in the development of children when they are as young as two or three years old (Foster, 2001). Family meals help keep the lines of communication open through the teen years, when it is really important. A simple meal eaten together as a family is a way to help families reconnect after a busy day. This time together helps keep the family strong. Getting older children home for dinner can be a challenge. In a survey conducted by the Families and Work Institute, just 34% of teenagers said they share one meal a day with one or both parents. Seventy-eight percent of parents said they dine daily with kids ages four to seven years old (Curran, 2003). Though it is harder to eat together as a family as children's lives get busier with activities and friends, keeping them connected is vital to the strength of the family unit. Experts say teenagers who feel emotionally close to their families are far less likely to engage in risky behaviors and activities (Smolak & Levine, 1995). Family meals are also a way in which parents can celebrate accomplishments. This can give children a self-esteem boost and improve their overall confidence (Stockmyer, 2001). Experts have stated that regular family meals provide great benefits, as family members have no choice but to face and focus on each other. Although all families have conflicts, family meals teach kids that there is a safe place to come together (Stockmyer, 2001).Family Meals Impact Nutritional Quality of Diets

The family mealtime environment has great potential to affect the eating behaviors of youth in the family. Research shows that the current dietary patterns of adolescents put them at risk for adult chronic disease and that the family plays an important role in determining the dietary patterns of youth (Kalish, 2001). Parents have a strong influence on food availability and eating practices of children from infancy through their adolescence. Within the context of the family environment, adolescents learn important values about eating well and staying healthy (Nudo, 2002). These lessons may be learned in families through instruction, reinforcement, modeling, and exposure to healthful foods (Nudo, 2002). Families who regularly consume meals together in the home have also been reported to have a lower intake of fried foods and soft drinks (Kalish, 2001). Several studies also suggest that foods obtained at home have less total fat, saturated fat, cholesterol, and sodium than foods obtained away from the home (Smolak & Levine, 1995).The research reviewed prior to conducting this research study indicated that current family mealtime practices are far from ideal. The goal for completing this study was to expand on current research by examining present mealtime patterns and their effects on the well-being of the family unit. The purpose of this study was to determine how the various family mealtime practices of faculty and staff within the college of business and applied sciences at a mid-sized Midwestern liberal arts university influence family dynamics. Specific research questions were as follows:

1. What is the frequency of meals per week consumed as a family?

2. Which meal is typically consumed together as a family?

3. What are the influencing factors on why families do or do not choose to eat together?

4. Do the participants perceive the family meal to strengthen the family unit?Method

This section presents the investigative methods and procedures for this study including data collection, sample, and statistical procedures. A researcher-developed survey was administered to a convenience sample of 50 faculty and staff.Data Collection

The electronic survey (Appendix A) contained 24 multiple choice questions. Question 10 specifically addressed research question one, regarding the frequency of meals per week consumed as a family. Additionally, questions 12-16 addressed the typical consumption during the meal. Questions 11 and 18 reflected the environment in which the meals were consumed as a family. Question 17 addressed research question two, regarding the meal most frequently consumed as a family. Research question three was addressed in questions 21 and 23. Research question four was addressed in question 24. Questions 1 through 9 addressed family demographic information, and questions 19, 20, and 22 addressed the meal preparation and serving. One family and consumer sciences professor examined face validity.Sample

The subjects for this study were faculty and staff in the Lumpkin College of Business and Applied Sciences at Eastern Illinois University during the spring semester of 2005. Approval was granted by the Institutional Review Board to continue to pursue this research project prior to distributing the questionnaire. The questionnaire was sent out to all faculty and staff in the college of business and applied sciences via e-mail. The e-mail was sent to a total of 143 potential participants. Fifty of these participants responded with a completed questionnaire, making a 35% response rate for this research study. The e-mail stated that the questionnaire was part of a study assessing current family mealtime patterns and their effects on the health and well-being of household inhabitants. Subjects were informed that participation in the study was voluntary and that the duration of their participation in the study included only completing the questionnaire. It was also specified that by responding to the e-mail and completing the questionnaire, they were giving consent to participate in the research study. The data collected from fifty faculty and staff employees are discussed in subsequent sections.Statistical Procedures

The answers on each survey were electronically tabulated. Descriptive statistics in the form of frequency data were calculated.Results and Discussion

Demographics

There were a total of 50 faculty and staff employees in the study: 21 males (42%) and 29 females (58%). Combined annual family income and the working status of household inhabitants are also indicated.Research Question One

What is the frequency of meals per week consumed as a family?

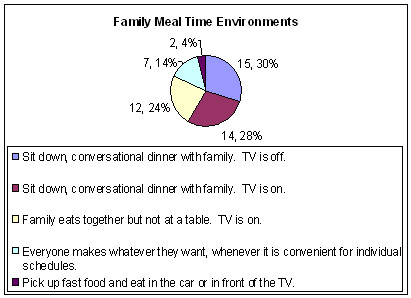

The results indicate that 52% (n=26) of participant's families consume a meal together 7 or more times per week, 24% (n=12) 5-6 times, 8% (n=4) 3-4 times, 12% (n=46) 1-2 times, and 4% (n=2) of participants stated they never consume meals together as a family. Additionally, 88% (n=44) of participants typically consume family meals at a set dining room table or at the kitchen table. The other 12% (n=6) of participants consume family meals in the family room, at a restaurant, or not at all.

These results differ from previous research regarding the frequency of meals consumed per week as a family. As stated in the review of literature, in a previous study of 15,202 adolescents, 14.0% reported eating family meals never, 19.1% reported one to two times per week, 21.5% reported three or four times per week, 18.9% reported five or six times per week, 18% reported seven times per week, and 18% reported eating meals as a family more than seven times per week (Escobar, 1999). The 52% of participants who indicated that they consume family meals together 7 or more times a week in this study provide a more promising result than the 18% reported in the 1999 study. Although the results from this research still represent eating together as a family to be a challenge for many families, some results show a possible increase in the consumption of family meals.

Research Question Two

Which meal is typically consumed together as a family?

Eighty-eight percent (n=44) of participants most frequently consume dinner as a family, 4% (n=2) consume lunch, and 8% (n=4) reported breakfast as the meal most frequently consumed as a family. Although most participants indicated sufficient starch and meat/protein intake at dinner, 30% (n=15) of participants indicated no dairy intake, 38% (n=19) indicated no fruit intake, and 28% (n=14) of participants typically consume zero servings of vegetables at dinner. The research results also indicate that 60% (n=30) of participants spend only 15-20 minutes preparing family meals. In this study, meal preparation was most often a joint effort by both parents and served most often by the mother.

The results from this study correspond with previous studies regarding dinner as the most frequently consumed meal as a family. Additionally, prior research indicated that the lack of regular family meal times negatively impact the nutritional quality of diets, especially in children. Other studies have demonstrated that the consumption of family meals leads to eating more fruits and vegetables and an improved overall dietary quality with higher intake of several nutrients including calcium, fiber, iron, folate, vitamin C, and B vitamins (Kalish 2001). Other findings from previous studies provide clear evidence of a strong, positive association between frequency of family meals and the quality of dietary intake.

Table 1

Research Question 3What are the influencing factors on why families do or do not choose to eat together?

Ninety percent (n=45) of participants indicated that their children have busy schedules most days of the week. Forty-six percent (n=23) of survey participants also indicated that they arrive home from work many days after 7:00 p.m. The combination of these two factors may provide a challenge for many families to make family meals a part of their daily regimen. Seventy-eight percent (n=39) of participants indicated that their children enjoy eating together as a family, so it can be postulated by this study that children's attitudes about family meals is not a particular obstacle.

Previous research studies have concluded that the increasing demands of work schedules as well as the increasing amount of children involved in extracurricular activities, have presented a challenge for many families to consume meals together. The results from this research study concur with these conclusions. Many families find it difficult to make family meal time a priority. This research has expanded upon the preceding research recognizing today's hectic lifestyle of many children and parents to be a contributing factor to the lack of regular meal times.

Research Question 4

Do the participants perceive the family meal to strengthen the family unit?

Ninety-six percent (n=48) of participants perceived family mealtimes to strengthen their family unit. Further research is needed to substantiate this result.

Conclusions

Although the sample size used for this study is relatively small, some conclusions can be made regarding the data that was collected and analyzed in this study. The results of this research study suggest that (a) family meals have the potential to contribute positively to the family unit, (b) regular family meals may help improve the nutritional adequacy of the diet, and (c) busy schedules of parents and children may have resulted in a decrease in the frequency of family meals.

Recommendations for Further Study

The results of this study provide information regarding the typical consumption of meals together as a family and on factors influencing these meal patterns. Additional questions pertaining to the effects of family mealtime patterns on the health and well being of the household inhabitants warrant further investigation. The following recommendations for further research and study are offered:

1. Replicate the study, using a population, to determine the effects of family mealtime practices on the household inhabitants.

2. Conduct more research on the specific ways family meals may strengthen the family unit.

3. Study the effects of family mealtimes on the social development of children.

4. Conduct a qualitative study examining the barriers to family meal times.References

Cox, M. (2002). Reinventing the family dinner. Good Housekeeping, 234(4), 75-78.

Curran, D. R. (2001). Traits of a Healthy Family (pp. 31-43). NY: Ballantine Books.

Fiese, B. H., Tomcho, T. J., Douglas, M., Josephs, K., Poltrock, S., & Baker, T. (2002). A review of 50 Years of Research on Naturally Occurring Family Routines and Rituals: Cause for Celebration? Journal of Family Psychology, 57(6), 381-389.Foster, E. (2001). Dinner talk: Cultural patterns of sociability and socialization in family discourse. Southern Communication Journal, 66(2), 168-169.

Gillespie & Gillespie. (2004). Family Mealtime: Inviting Everyone to the Table, Society of Nutrition Education 37th Annual Conference, (pp.1-6).

Gillman, M. W., Rifas-Shiman, S. L., & Frazier, A. L. (2000). Family dinner and diet quality among Older children and adolescents. Journal of Family Medicine, 40(9), 509-512.

Kalish, N. (2001). Why family dinner is worth it. Parenting Magazine, 12(9), 133-135.

Meiselman, H. L. (2000). Dimensions of the Meal. SNE 27th Annual Conference, 1.

Minami, M. (1997). Dinner Talk: Cultural Patterns of Sociability and Socialization in Family Discourse. Bilingual Research Journal, 21(4), 431-435.

Neumark-Sztainer, D., Story, M., Perry, C., & Casey, M. A. (1999). Factors influencing food choices of adolescents: Findings from focus-group discussion with adolescents. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 99(3), 929-934.

Neumark-Sztainer, D., Hannan, P. J., Story, M., Croll, J., & Perry, C. (2003). Family meal patterns: Associations with sociodemographic characteristics and improved dietary intake among adolescents. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 103(3), 317-322.

Neumark-Sztainer, D., Story, M. A., Ackard, M., Moe, D., & Perry, J. (2000). The "family meal": View of adolescents. Journal of Nutrition Education, 32(6), 329-334.

Nudo, L. (2000). Make a dinner date tonight! Prevention, 54(7), 48-49.

Renkyl, M. (2000). In praise of family meals. Family Economics and Nutrition Review, 12(4), 33-44.

Smolak, L., & Levine, M. (1995). Ten things parents can do to help prevent eating disorders in their children. Healthy Weight Journal, 9(5), 92-94.Stockmyer, C. (2001). Remember when mom wanted you home for dinner? Nutrition Reviews, 59(2), 57-60.

Whitaker, R. C., Deeks, C. M., Gaughcum, A. E., Specker, B. L., (2000). The relationship of childhood obesity to parent eating behavior. United States Drug Aministration, 213-242.

Appendix A

Family Mealtime Questionnaire

1. What is the size of your family?

a. 1

b. 2

c. 3

d. 4

e. 5 or more2. Are you a male or female?

a. male

b. female3. What is the combined annual family income at your home?

a. < 30,000

b. $31,000-65,000

c. $66,000-95,000

d. $96,000-149,000

e. > $150,0004. Which best describes the working status of household inhabitants?

a. One working parent, one parent stays home

b. Two working parents

c. One single working parent

d. Neither parent currently working5. Number of people living in your household pre school age or younger.

a. 0

b. 1

c. 2

d. 3

e. 4 or more6. Number of people living in your household of elementary school age.

a. 0

b. 1

c. 2

d. 3

e. 4 or more7. Number of people living in your household of middle school age.

a. 0

b. 1

c. 2

d. 3

e. 4 or more8. Number of people living in your household of high school age.

a. 0

b. 1

c. 2

d. 3

e. 4 or more9. You currently have no children living at home.

a. Not true

b. True10. How frequently do you eat together as a family during a typical week?

a. 7 or more

b. 5-6 times

c. 3-4 times

d. 1-2 times

e. Never11. Which of the following describes the mealtime environment at your home?

a. Sit down, conversational dinner with family. Television is off.

b. Sit down, conversational dinner with family. Television is on.

c. Family eats together but not at a table, television is on.

d. All members make whatever they want, whenever it is convenient for their schedules.

e. Pick up fast food and eat in the car or in front of the television12. How many servings of bread are consumed at dinner on a typical day?

a. 0

b. 1

c. 2

d. 3

e. 4 or more13. How many servings of meat/protein are consumed at dinner on a typical day?

a. 0

b. 1

c. 2

d. 3

e. 4 or more14. How many servings of dairy are consumed at dinner on a typical day?

a. 0

b. 1

c. 2

d. 3

e. 4 or more15. How many servings of fruit are consumed at dinner on a typical day?

a. 0

b. 1

c. 2

d. 3

e. 4 or more16. How many servings of vegetables are consumed at dinner on a typical day?

a. 0

b. 1

c. 2

d. 3

e. 4 or more17. Which meal is most frequently consumed as a family?

a. Breakfast

b. Lunch

c. Dinner18. Where do you most frequently consume meals as a family?

a. At a set dining room table.

b. At the kitchen table.

c. In the family room

d. At a restaurant.

e. We don't ever eat meals together as a family.19. Who usually prepares meals at your household?

a. Mother

b. Father

c. It is a joint effort by both parents.

d. All members eat what they want when they have time.

e. The grocery store (ex: already prepared food from Wal-Mart).20. What is the average length of time spent on preparing family meals?

a. 15-20 minutes

b. 20-40 minutes

c. 40-60 minutes

d. An hour or more21. Which best describes your cooking abilities?

a. I consider myself to be a good cook, when I have the time.

b. My family complains about how I cook.

c. Nobody ever taught me how to cook..

d. I can cook basic and repeated meals.

e. I can't cook at all.22. Who serves meals at your household?

a. Mother

b. Father

c. Nobody serves meals

d. The delivery person

e. All family members23. Please circle all that apply to your family?

a. Children have busy schedules most days of the week.

b. You arrive home from work many days after 7:00pm.

c. Meals are prepared more on weekends than during the weekdays.

d. Meals are prepared more often during weekdays than during weekends.

e. Children enjoy eating together as a family.24. Do you believe family mealtime strengthens your family?

a. Yes

b. No

|