Hispanic Working Women's Business Jacket Purchase and Consumption

Ana Stoyanova and Seulhee Yoo*

Texas Tech University

Abstract

According to the 2002 U.S. Census Bureau report, the fast demographic growth of the Hispanic population is paralleled by substantial increase in their disposable income. In addition, numerous studies have shown that the Hispanic population is very fashion conscious and spends a considerable portion of its household income on apparel items. As a result, Hispanics are becoming an important marketing segment for apparel designers, manufacturers, and retailers. However, this particular ethnic group displays specific apparel purchase and consumption patterns. The purpose of the present study was to explore demographic and socio-economic characteristics of Hispanic working women as well as their business jacket purchase and consumption behavior. A self-administered questionnaire was developed and research data were gathered via national mail survey and drop-off survey in Texas. A total of 91 Hispanic working women were identified and included in data analysis. The findings indicate that the majority of respondents owned between two and ten business jackets. The respondents wore business jackets most often during winter. Higher preference for purchasing business jackets separately than as a suit was demonstrated by the respondents. The majority of the respondents exhibited relatively high preference for combining business jackets with pants. Cash or check was used as a preferred payment method for purchasing professional apparel, and a department store was a preferred store type. The authors feel that the Hispanic population needs to be broken down into several subgroups (Mexican, Cuban, Puerto-Rican, etc.) to better study their apparel purchase and consumption.

Introduction

According to the 2002 U.S. Census Bureau report, Hispanics are the fastest growing ethnic group with a 70% population increase since 1990 and an additional 10% increase since 2000. The fast pace of growth will make the Hispanic American population the second largest Hispanic market in the world and by 2025 the Hispanic population in the U.S. is projected to number 86.9 million (Stephens, 2001). The demographic growth of the Hispanic population is accompanied by substantial growth of disposable income. The 2002 U.S. Census Bureau Report projects that the buying power of the Hispanic population will reach $927 billion in 2007. Hispanic Market Resource Guide, a publication of the San Diego Ad Club (as cited in Stephens, 2001), reports that the spending power of the Hispanic American population is $927 million daily and $338.6 billion annually.

In addition to this, several reports (Cotton Inc. 2001 report as cited in "African-American"; the Simmons Market Research Bureau 2001 report as cited in Gardyn & Fetto, 2003) demonstrate that the Hispanic population is very fashion conscious and spends a considerable portion of its income on apparel items. Furthermore, a survey by the University of Georgia and Market Segment Research & Consulting (as cited in Romero, 1997) found that young Hispanics are more willing to spend money on clothing than any other ethnic group. Moreover, the age breakdown of the Hispanic versus Caucasian population (as a percentage of the total population) is in favor of the Hispanics: 34.4% of Hispanics are below 18 years old compared to 22.8% of Caucasian (U.S. Census Bureau Report, 2002). The young and very fashion conscious Hispanic population has recently become a target for apparel designers, manufacturers, and retailers who acknowledge the potential of this marketing niche (Diebel, 2003).The unprecedented growth of the Hispanic population in the United States started to significantly affect the consumer spending in the late 1990s and will continue in the future (U.S. Census Bureau Report, 2002). Studying and analyzing the specific characteristics of the Hispanics is extremely important for the development of successful marketing strategies targeting this ethnic group. With these facts in mind, the present study was designed to explore demographic and socio-economic characteristics of Hispanic working women as well as their business jacket purchase and consumption.

Literature Review

The Hispanics

The Hispanic population is not homogenous and consists of three major subgroups geographically concentrated in specific parts of the United States. Mexican Americans represent the biggest subgroup of the Hispanic population. Due to the proximity and common border with Mexico this segment of the Hispanic population generally resides in the southwestern states (California, Texas, Arizona, New Mexico, and Colorado). The second largest Hispanic group is Puerto Ricans and is located predominantly in New York. The third largest subgroup of the Hispanic population is Cubans who tend to be geographically concentrated in Florida. According to the 2002 U.S.Census Bureau report the Hispanic population outnumbers by a big margin the Non-Hispanic Whites as percentage of the total population in the Western states (44.2% Hispanics versus 19.2% Non-Hispanic Whites) and by a narrow margin in the southern states (34.8% Hispanics versus 33.3% Non-Hispanic Whites).

According to the 2002 U.S. Census Bureau report Cuban Americans have the highest educational attainment of all Hispanics. The majority (70.8%) of Cubans have high school diploma or higher compared to 66.8% of Puerto Ricans and 50.6% of Mexican Americans. Roughly nineteen percent of Cubans attain Bachelor's degree or higher, whereas 17.3% of Central and South Americans and only 7.6% of Mexican Americans can claim the same educational attainment (U.S. Census Bureau, 2002). Puerto Ricans and Cubans are the most affluent Hispanic subgroups as 34.8% and 34.3% of them respectively claim to have annual household income of $35,000 and more (U.S. Census Bureau, 2002).

The U.S. Census Bureau report claims that 26.5% of the Hispanic households consist of five people or more. Mexican Americans (30.6%) are most likely to live in big households whereas only 16.8% of Puerto Ricans and 10.6% of Cuban Americans live in families of five or more.

Apparel Shopping Behavior

The Hispanic population displays distinctive shopping behavior and consumption. Particularly, Mexican, Puerto Rican, and Cuban Americans differ significantly in their shopping behavior and consumption patterns (Valencia, 1982, as cited in Pasarell, 1995). Previous research argued that these differences could be due to cultural and ethnic rather than socioeconomic factors (Brandon & Forney, 2002; Valencia, 1982, as cited in Pasarell, 1995). Moreover, the 2001 Cotton Inc. report (as cited in "African-American") found out that Hispanic women spend more money on apparel than Caucasian women. Twenty-four percent of Hispanic women spend $101-$200 a month on clothes compared to 15% of Caucasian women. Fourteen percent of Hispanic women spend more than $200 a month on apparel, whereas 12% of Caucasian women allocate the same amount of money for clothes.

Pasarell (1995) reported that Caribbean women enjoy shopping at the store and avoid catalogues. Although paying cash or with a check was the type of payment preferred by the majority of Caribbean women, roughly 30% preferred using credit cards (Pasarell, 1995). The same study by Pasarell (1995) found that department stores ranked highest as an apparel purchasing location among Caribbean women. Shopping is a social activity for Hispanics and 36% of Hispanics enjoy shopping with family and friends according to the Simmons Market Research Bureau (as cited in Gardyn & Fetto, 2003).

However, Pasarell (1995) pointed out that Hispanic women are moving away from the family stereotype and might be seeking higher career goals than ever before.

Design Preference

Numerous studies demonstrate that Hispanics place high importance on displaying status symbols (Brandon & Forney, 2002; Gardyn & Fetto, 2003; Pasarell, 1995; Stoyanova & Yoo, 2003). Brandon and Forney (2002) found that Hispanic women prefer to dress in a more formal rather than casual manner. Oliver and Christian (1994) support this distinctive preference for more formal attire. Their study reported that Hispanic women were more willing to spend money on fine quality apparel and exhibited higher preference on designer and haute couture labels. However, Pasarell (1995) did not support this assumption. The findings of Pasarell's study demonstrate that Caribbean women did not show any affinity for custom-made or designer garments.

Pasarell (1995) pointed out that women of Caribbean origin exhibit high tendency for wearing bright colors all year round. The study also claimed that due to the limited assortment of brightly colored clothes Caribbean women buy clothes in neutral and subdued colors. Pasarell (1995) noted a marked shift from the traditionally high emphasis placed by Hispanic women on style, color, brand, uniqueness, and social symbol. The Caribbean women included in Pasarell's study rated garment functionality, ease-of-care, quality, and price as the most important factors contributing to their selection of apparel.

Previous research (Brandon & Forney, 2002; Gardyn & Fetto, 2003; Pasarell, 1995) showed that Hispanic women are very fashion conscious. Keeping up with the latest fashion is important to 46% of Hispanic women compared to 36% of Caucasian women according to the Simmons Market Research Bureau (as cited in Gardyn & Fetto, 2003). Pasarell (1995) supports this fact in her study of Caribbean women. The majority of the respondents in the study preferred buying fashionable rather than classic clothes. However, Pasarell (1995) surprisingly suggested that women who are more fashion conscious prefer to buy classic clothes because they do not go out of fashion so quickly.

Having these facts in mind, the current study was designed to address Hispanic working women's business jacket purchase and consumption behavior.

Research Design

A self-administered questionnaire was designed to elicit demographic and socio-economic information of Hispanic working women as well as their business jacket purchase and consumption related information. The questionnaire was pilot tested before its final administration.

Data Collection

The research data were collected utilizing two survey techniques. The first data collection followed Salant and Dillman's (1994) drop-off survey technique and was administered to University employees in Texas. The data collection included three office visits. The first office visit was to distribute the survey. The second office visit, followed in three business days after the first one, was a reminder. The third office visit took place three business days after the second one, and its purpose was to collect the survey.

For collection of the second data, Dillman's (1994) national mail survey technique was utilized in part. The national mail survey consisted of three mailings: a notification card informing the recipient about the upcoming questionnaire, a questionnaire sent four days after the notification card, and a reminder card sent a week after the questionnaire. The data used for this particular study was a segment of the total data collected for non-Caucasian working women study since 2002.

Final Sample

During the first data collection, a total of 130 questionnaires were distributed. Of the 130 questionnaires, 98 questionnaires were returned (75.4% response rate), of which 79 questionnaires were deemed usable. Of the 79 non-Caucasian respondents, 46 were Hispanic women.

For the national mail survey, a total of 2400 questionnaires were mailed to randomly selected non-Caucasian working women who wore business jackets to work at least once a week. Of the 2400 questionnaires, 198 questionnaires (8.3% response rate) were returned, of which 45 Hispanic working women were identified and included in the data analysis. Combining the data collected from the two surveys, the final Hispanic working women sample composed of 91 Hispanic working women.

Reliability of the Scales

Cronbach's alpha coefficient was utilized to test instrument reliability. The instruments' overall alpha coefficient demonstrated high reliability (a = .86).

Results

The respondents' age varied between 20 and 68 years and the mean age was 40.9 years. The respondents' average height was 5'3" and the average weight was 149.2 lbs. The mean household income of the respondents was $43,962 a year, and the average family size was 3.3. The majority of the respondents (61%) were married, while 19% were single, never married, and 13% were divorced. Thirty-two percent of the respondents had completed some college work, 22% had a high school diploma, 21% had associate degree, 14% had Bachelor's degree, and 10% had Master's, Doctoral, Post doctoral, or Professional degree (see Table 1).

Table 1.� Demographic and Socio-Economic Characteristics of Hispanic Working Women

Characteristics

����������� n

��������� %

Characteristics

����������� n

���������� %

Characteristics ����������� n

���������� %

Age

Generally Purchased Dress Size

Employment Status (M=40.9, SD=10.25)

(M=, SD=)

Full-time

80

87.91

��� 18-25 years

8

8.89

Size 2 or smaller

5

5.61

Part-time

11

12.09

��� 26-35 years

20

22.21

Size 3-Size 4

3

3.37

��� 36-45 years

32

35.54

Size 5-Size 6

11

12.36

Career Orientation ��� 46-55 years

23

25.54

Size 7-Size 8

12

13.48

Just-a-job

48

52.75

��� 56+

7

7.77

Size 9-size 10

14

15.73

Career

43

47.25

No response

1

1.11

Size 11-Size 14

27

30.34

Size 15-Size 20

13

14.61

Percentage of Financial

Contribution to the

Total Household IncomeHeight

Size 21-Size 26

4

4.5

(M=63.3, SD=2.35)

��� 5' or shorter

10

10.99

10% or below

8

9.76

��� 5'1"-5'4"

41

45.06

Figure Type 11%-20%

3

3.66

��� 5'5"-5'7"

32

35.16

Ideal

18

20.00

21%-30%

8

9.76

��� 5'8" or taller

8

8.8

�����������

Triangular

17

18.89

31%-40%

11

13.41

Inverted-triangular

5

5.56

41%-50%

5

6.10

Rectangular

8

8.89

51%-60%

10

12.20

Weight

Hourglass

11

12.22

61%-70%

5

6.10

(M=, SD=)

Diamond-shaped

11

12.22

71%-80%

4

4.88

��� 101 lbs-120 lbs

12

13.2

Tubular

5

5.56

81%-90%

6

7.32

��� 121 lbs-140 lbs

30

33

Rounded

14

15.56

91%-100%

22

26.83

��� 141 lbs-160 lbs

22

24.2

No response

1

1.11

No response

9

10.98

��� 161 lbs-180 lbs

14

15.4

��� 181 lbs-200 lbs

8

8.8

Marital Status ���������

��� 201 lbs or more

4

4.4

Single, never married

17

18.68

��� No response

1

1.1

Divorced

12

13.19

Married

56

61.54

Body Frame Size

Widowed

2��

2.20

Separated

3

3.30

��� Petite

15

16.48

Cohabiting

1

1.10

��� Small

13

14.29

��� Medium

42

46.15

Education ��� Large

12

13.19

High school

0

0.00

��� Extra-Large

9

9.89

Some college

0

0.00

Associate degree

20

21.98

Generally Purchased

Bachelor's degree

30

32.97

Some graduate work

19

20.88

Garment Size Category

Master's degree

13

14.29

��� Petite

38

42.22

Doctoral degree

0

0.00

��� Tall

2

2.22

Other

3

3.30

��� Misses

32

35.56

��� Women's

18

20.00

Note. The percentage total for each characteristic may not add up to 100 due to the rounding. The no response rate was excluded from the frequency and percentage calculation.

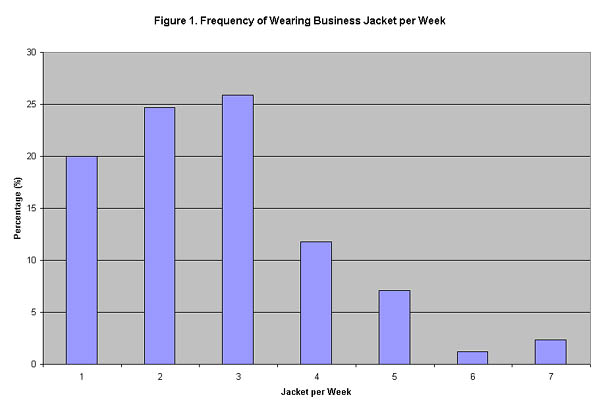

For the business jacket purchase and consumption, twenty-six percent of the respondents wore business jackets three times a week, 24.5% of the respondents wore business jackets twice a week, 20% wore business jackets once a week, and 12% wore business jackets four times a week (see Figure 1).

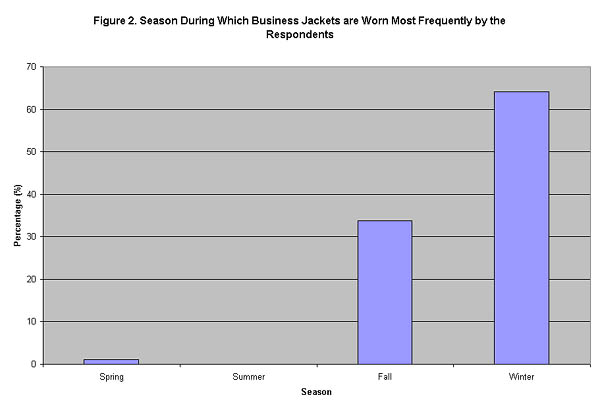

The respondents wore business jackets most often during cold seasons (see Figure 2). More than half of the respondents (64%) said they wore business jackets most often during winter, while 33.7% said that they wore business jackets most often during fall. The majority of the respondents owned between one and four fall business jackets (71%) and between one and five winter business jackets (75%). Summer and spring were very unpopular seasons for wearing business jackets. Thirty-five percent of the respondents did not possess any summer business jackets and 20.7% of the respondents did not possess any spring jackets.

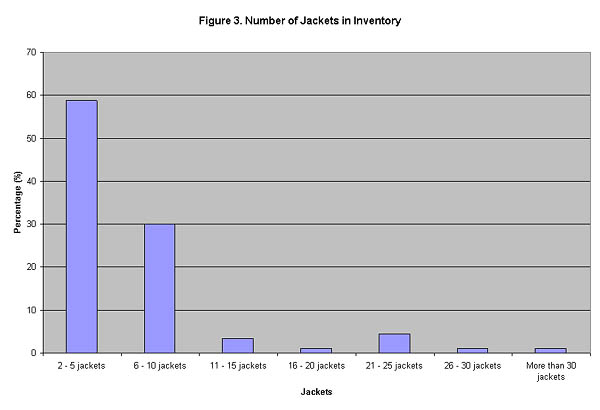

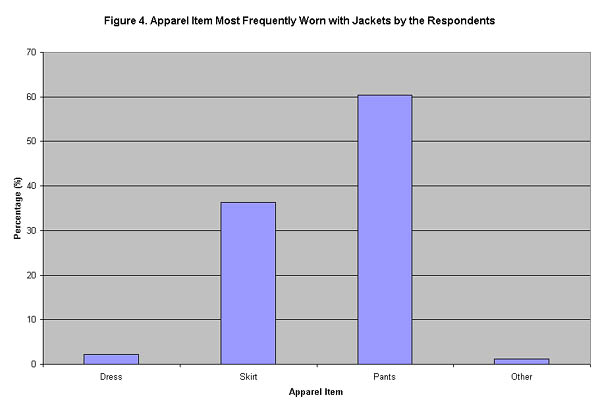

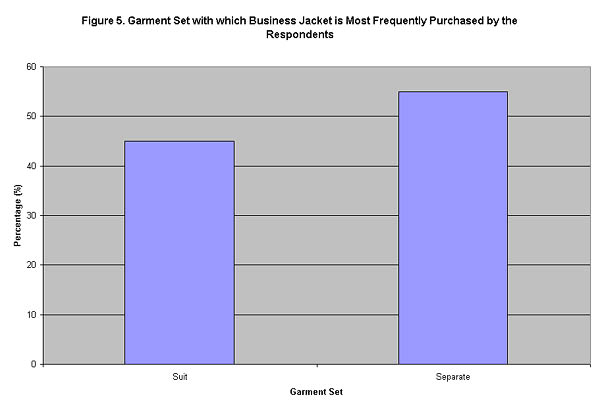

The majority of the respondents (86.7%) owned between two and ten business jackets: 10% owned two jackets, 17.8% owned three jackets, 13.3% owned four jackets, 15.6% owned five jackets. 8.9% owned eight jackets, and 10% owned ten jackets (see Figure 3). More than half of the respondents (60.4%) coordinated their business jackets with pants, while 36.3% of the respondents preferred a skirt as the coordinating piece (see Figure 4). Approximately, half the respondents (54.9%) purchased their business jackets separately, while the other half (45%) purchased business jackets as suit (see Figure 5).

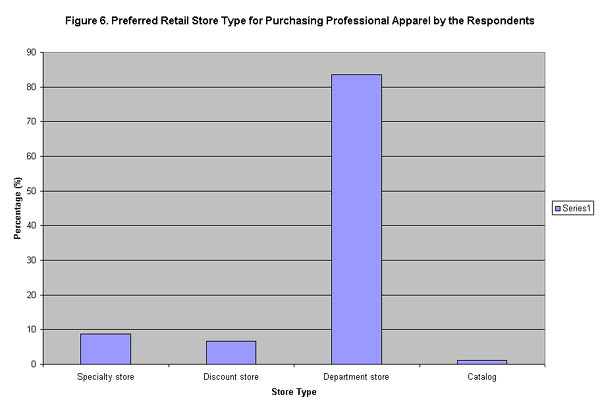

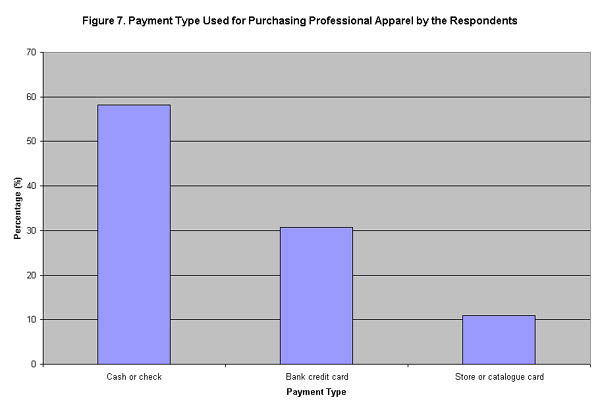

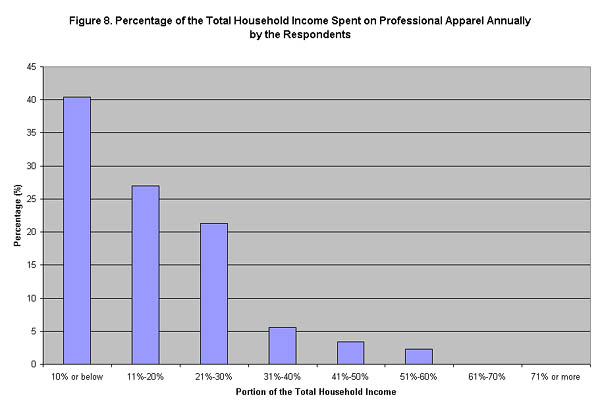

The majority of the respondents (83%) purchased their jackets at department stores, while 8.8% and 6.6% purchased their jackets at specialty and discount stores, respectively (see Figure 6). The type of payment most commonly preferred was cash or check (58.2%) followed by bank credit card (30.7%) and store or catalogue card (10.99%) (see Figure 7). Less than half of the respondents (40.45%) allocated 10% or below of their household income on professional attire, 27% of the respondents spent 11% - 20% of their income on professional attire, 21.35% spent 21% - 30% of their household income on professional attire, and 11.24% of the respondents spent 31% - 60% of their income on professional attire (see Figure 8).

Discussion

The findings of the study were in agreement with Pasarell (1995). The preferred payment type was found to be cash or check, but credit card payment was also popular. As Pasarell (1995) suggested, credit card companies might target the potentially lucrative Hispanic market with more direct and specifically Hispanic-oriented marketing strategies.

This study also supported Pasarell (1995) in the type of store mostly preferred by Hispanic women. The majority of the respondents preferred to purchase professional attire at department stores. This may be attributed to the higher social status generally attributed to shopping at department stores. As previous research has found, exhibiting status symbols is very important for the Hispanic population (Brandon & Forney, 2002; Oliver & Christian, 1994).

The respondents exhibited higher preference for purchasing business jackets separately than as a suit. The higher demand for versatility placed on business jackets by the respondents may be one possible reason for this may be. Business jackets purchased separately allow for flexible combinations with clothing items that already exist in a working woman's wardrobe. Another reason for the higher preference for business jackets purchased separately may be that they are usually combined with a piece in different color and fabric. As the result is often a relaxed and slightly casual look, this particular type of business jackets is appropriate attire for everyday business affairs and casual meetings with colleagues. The business suit, as a contrast, contributes to a total, "head-to-toe" look that suggests power, dominance and conservativeness. It is the most appropriate attire for formal business meetings and is mandatory for executives and company representatives. Therefore, working women in higher position would prefer to purchase business jackets as a suit whereas working women in lower rank would prefer to purchase business jackets separately. The higher preference for business jackets purchased separately may be attributed to the professional position held by the respondents: probably the majority of the respondents did not hold supervisor or executive positions.

The respondents demonstrated relatively high preference for combining their business jackets with pants. One possible reason for this might be the flattering effect pants have when combined with a jacket. Pants, especially when they are in the same color as the jacket, visually elongate the body and make wide hips and legs appear narrower. As Hispanic women are generally perceived as having curved figures, business jackets combined with pants may be considered the most appropriate attire for the Hispanic body type. Another possible explanation for the relatively high preference for business jackets combined with pants may be the high awareness for fashion trends demonstrated by Hispanic women (Gardyn & Fetto, 2003; Brandon & Forney, 2002; Pasarell, 1995). Business pants suits are considered more fashionable and less traditional and conservative as compared to business suits with skirt. Third possible reason for the relatively high preference for business jackets combined with pants is the high demand for comfort by the respondents. Generally speaking, pants are more comfortable than skirts because they do not restrict the body movement. The dynamic and fast-paced business activities make pants the most suitable clothing item for the working woman.

The majority of the respondents wore business jackets most often during winter. Business jackets help the body stay warm during cold weather and this may explain why business jackets are popular during the cold seasons (winter and fall) and are unpopular during the warm seasons (spring and summer).

The findings support Brandon and Forney (2002) and Oliver and Christian (1994) in their assumptions that Hispanic women like to dress in a more formal way. As the present study found out, the majority of Hispanic women own between two and ten business jackets. Business jackets, whether in suits or not, contribute to a more formal look than the business casual clothes.

The results of the study support the survey by the University of Georgia and Market Segment Research & Consulting (as cited in Romero, 1997) and the 2001 Cotton Inc. report (as cited in "African-American") in their claim that Hispanic women are more willing to spend considerable portion of their household income on apparel items. Roughly half of the respondents spend 10%-30% of their household income on professional attire and 10% spend over 30% on professional attire. Ethnic and cultural values may be the reason for the high importance placed on professional apparel. Making good impression about oneself and one's social status through clothing and personal appearance is a probable explanation of this tendency. Oliver and Christian (1994) found out that Hispanic women are more willing to purchase finer quality apparel than Caucasian women. Buying finer quality clothes that cost more might also account for the high portion of household income Hispanics spend on professional attire.

Previous research has pointed out significant demographic differences between the Hispanic subgroups. As there is a direct correlation between demographics and clothing purchase and consumption, separate studies on Mexican-Americans, Cuban-Americans, and Puerto-Rican Americans need to be undertaken.

References

African-American and Latina women are more likely to have spent more than $100 on Clothing in the past month than non-Hispanic Caucasian women. (2001). Marketing to Women, 14(8), 12.

Brandon, L. & Forney, J. (2002). Influences on female purchase motivations and product satisfaction: A comparison of casual and formal lifestyles and Anglo and Hispanic ethnicity. Journal of Family and Consumer Sciences, 94(1) 54-63.

Diebel, (2003). Marketers go after Latinos, big time. Retrieved February 13, 2003, from http://web.lexis-nexis.com/universe/decument

Gardyn, R., & Fetto, J. (2003). Race, ethnicity, and the way we shop. American Demographics, 25(1), 30-33.

Oliver, B., & Christian, J. (1994). Cross-cultural advertising: an analysis of Hispanic and Anglo magazines. Journal of Home Economics, 86(1), 9-15.

Pasarell, Y. (1995). Hispanic women: lifestyles and apparel shopping patterns. Unpublished dissertation, Florida State University.

Romero, E. (1997). Latino designers move to meet fashion demands of Hispanic youth. Retrieved May 27, 2003, from

http://web.lexis-nexis.com/universe/decument

Stephens, P. (2001). Say it in Spanish. Retrieved May 27, 2003, from http://web.lexis-nexis.com/universe/decument

Stoyanova, A., & Yoo, S. (2003). Design preferences of non-Caucasian working women: A business jacket focus. Undergraduate Research Journal, Vol.2. [Online]. Retrieved April 20, 2004 from /urc/stoyanova.pdf

U.S. Census Bureau (2002). Annual report. Retrieved May 10, 2003, from http://www.census.gov/population/www/socdemo/race/api.html

http://www.census.gov/prod/2003pubs/p20-545.pdf

|