The Objectification and Dismemberment of Women in the Media

Kacey D. Greening

Capital University

Abstract

Extensive research has demonstrated the negative results of female objectification in the media. Depression, appearance anxiety, body shame, sexual dysfunction, and eating disorders are only a few among the growing list of repercussions (Fredrickson & Noll, 1997). In addition to the objectification of women, the media commits another assault on the dignity of women. This assault is the dismemberment of women, and it has not received the attention it deserves (Kilbourne, 2002). Thus, the primary goal of this study is to examine the prevalence and implications of the dismemberment of women in our society. The secondary goal is to suggest that the negative consequences of dismemberment are comparable to the negative consequences of objectification.

Introduction

Kilbourne (2002) pointed out that advertising is a 100 billion dollar a year industry. Each day we are exposed to more than 2000 ads. Advertising can be one of the most powerful sources of education in our society. Many women feel pressured to conform to the beauty standards of our culture and are willing to go to great lengths to manipulate and change their faces and bodies. Kilbourne suggests that women are conditioned to view their faces as masks and their bodies as objects. Through the mass media, women discover that their bodies and faces are in need of alteration, augmentation, and disguise. In addition, women are taught to internalize an observer’s perspective of their own bodies. This phenomenon is called objectification (Fredrickson & Noll, 1997). Advertisements are loaded with objectified women, and only recently have the effects of objectification been explored. However, the effects of the dismemberment of women in advertising have been neglected. Dismemberment advertisements highlight one part of a woman’s body while ignoring all the other parts of her body. Dismemberment ads portray women with missing appendages or substitute appendages. Of course the ads are only symbolic of dismemberment, but the symbolic imagery creates nearly the same effect. This study highlights the nature and implications of objectification and requests a similar exploration of the nature and implications of dismemberment advertisements. It is important to note that advertisements are not the cause of the problems, per se, but they contribute to them by fostering an environment in which the selling of women's bodies is seen as acceptable.

Discussion

The Prevalence of Objectification

Sexualized messages permeate American culture. The most prominent means of transporting this sexualized female identity is through the mass media. Female objectification was once thought imponderable but, through a growing body of research, this belief has been proven wrong. The existence and the implications of female objectification have recently been explored. Empirical studies have indicated that women are overwhelmingly targeted more for sexually objectifying treatment than men (Gardner, 1980; Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997; Henley, 1977; Van Zoonen, 1994).

Fredrickson and Roberts (1997) coined the term, objectification theory, which suggests that our culture socializes girls and women to internalize an observer’s perspective on their own bodies. When young girls and women internalize an observer’s perspective of their own bodies, they live much of their life in the third-person. This is called self-objectification. In other words, females learn to be more concerned with observable body attributes rather than focusing on non-observable body attributes such as feelings and internal bodily states. Fredrickson and Roberts (1997) suggest that appearance monitoring, which is present in self-objectification, can increase shame and appearance anxiety and diminish awareness of internal bodily states. These experiential consequences may contribute to the development of several mental health risks, including eating disorders, unipolar depression, and sexual dysfunction. The subsequent studies attest to the negative implications of objectifying the female body.

Copyrighted image removed by request of gallerystock.com

The original can be viewed here: Figure 1: Example of Objectification |

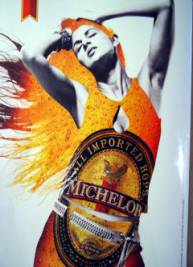

Figure 2: Example of Objectification |

The Implications of Objectification

Kuring and Tiggemann (2004) conducted a study consisting of 286 undergraduate students (115 men, 171 women). Participants were recruited from Psychology courses at the Flinders University of South Australia and participated in the study for course credit. Participants were administered a questionnaire that contained “measures of self-objectification and self-surveillance, measures of the proposed consequences of self-objectification (body shame, appearance anxiety, flow and awareness of internal bodily states), as well as the outcome variables of disordered eating and depressive mood” (301). The study found that self-objectification leads to self-surveillance that, in turn, leads to body shame and appearance anxiety and in both greater disordered eating and more depressed mood. This finding is only true for women. Contrarily, men experienced much lower levels of self-surveillance. However, the men who presented evidence of self-surveillance experienced increased body shame and appearance anxiety. It is noteworthy that men showed no presence of self-objectification, thus suggesting that women are overwhelmingly more likely to experience self-objectification and self-surveillance. The rare cases in which men experience self-surveillance, similar emotions and reactions are present (Kuring & Tiggemann, 2004).

Fredrickson, Noll, Quinn, Roberts, and Twenge (1998) found that self-objectification contributed to disordered eating directly. Seventy-two undergraduate women at Duke University participated in this study for partial course credit. Participants were tested individually in one-hour laboratory sessions. The participants were administered the Self-Objectification Questionnaire, which required them to rank the order and the significance of 12 body attributes by how important each is to their physical self-concept. In addition, an indirect measure of body shame was administered because emotion theorists have argued that shame is difficult to assess directly, in part because individuals may feel ashamed of being ashamed. To circumvent this difficulty, the self-report measure targeted the motivational and behavioral components of shame such as the desire to hide, escape, turn away, disappear, or become smaller, as well as the desire to change the failed aspects of the self (Fredrickson et al., 1998). Their hypothesis posits that anticipated body shame encourages women to participate in disordered eating. Oftentimes, women who engage in disordered eating are attempting to maintain or gain body satisfaction and avoid the dreaded experience of body shame. Their hypothesis received support. Thus, it can be safely assumed that our culture’s practice of sexual-objectification of the female body has profoundly negative effects on women, and disordered eating is only one of many.

Furthermore, it is imperative to note a study conducted by Baker, Towell, and Sivyer (1997). This study investigated the role of visual media by examining the relationship between body image dissatisfaction and abnormal eating attitudes in visually impaired women. Body dissatisfaction and abnormal eating attitudes are frequent effects of our culture’s promotion of an unattainable beauty ideal. Sixty women were recruited for this study (20 were congenitally blind, 20 were blinded in later life, and 20 were sighted). All subjects were aged between 20-35 years. The Body Shape Questionnaire was administered to measure the level of concern about body shape, and the Eating Attitudes Test was used to determine attitudes towards eating. The results revealed that congenitally blind women had significantly lower body dissatisfaction scores and more positive eating attitudes compared to women who were blinded later in life and sighted women. The results indicate that visual media may play a crucial role in the development and maintenance of body dissatisfaction and disordered eating (Baker et al., 1997).

In a study conducted by Gettman and Roberts (2004), a state of self-objectification was induced in a sample of 90 women. The participants were enrolled in an introductory psychology course at a Colorado public university. First, they were asked to unscramble manipulated sentences. While one group was primed with body competence, the other group was primed with self-objectification. Then, three questionnaires were administered to the participants. The first questionnaire consisted of questions about shame and disgust, which were drawn from research conducted by Tangney and colleagues (1996). The second measure was Dion’s Appearance Anxiety Scale. The third measure was the Appeal of Sex Scale. The results demonstrated that the self-objectification prime led to significantly higher levels of appearance anxiety. It also led to a decrease in the appeal of physical aspects of sex. This is the first piece of evidence that lends support to the prediction that objectification contributes to sexual dysfunction (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997). Perhaps sexualizing and objectifying women actually decreases their sex drive rather than increases their sex drive. It is possible that the words used in the self-objectification prime activated a sense of being “on display,” which may have caused women to feel self-conscious in regards to their performance. Masters and Johnson (1970) identified self-consciousness and “spectatoring” as key barriers to women’s comfort with sex. In addition, the shame and disgust many women experience about their bodies may shape their sexual attitudes and experiences. This argument received support through this study in which a negative correlation was present between shame and self-disgust and the appeal of physical sex (Gettman & Roberts, 2004).

In relation to intimacy and sexuality within male and female relationships, Brooks (1995) discussed the effects of the centerfold syndrome that is defined by five principal characteristics: voyeurism, objectification, trophyism, the need for validation, and the fear of true intimacy. Brooks mentioned several possible causes of the centerfold syndrome such as biology, instinct, and survival of the fittest. However, it is exceptionally interesting to note that of all the possibilities mentioned, Brooks found the socio-cultural explanation to be the most probable. Brooks claimed that the centerfold syndrome is a product of the way in which men have been taught to think about and experience relationships, intimacy, and sex. The widespread sexualization of women in our culture easily lends itself to the adoption of the Centerfold Syndrome. Men are not the only ones who have adopted this harmful attitude towards relationships, intimacy, and sex. Women can just as easily adopt a negative self-image and attitude, perpetuating the negative stereotypes about women, sexuality, intimacy, and relationships (Brooks, 1995).

The Dismemberment of Women in the Media

Indeed, the objectification of women is evident in our society where women are constantly sexualized, but the dismemberment of women has yet to receive the consideration and exploration it deserves. Kilbourne (2002) suggested that the dismemberment of women is a monstrous problem in advertising. Dismemberment ads focus on one part of the body, e.g., a woman’s breasts. Typically, dismemberment ads employ female body parts for the purpose of selling a product. Dismemberment ads promote the idea of separate entities. These ads overtly and covertly encourage a woman to view her body as many individual pieces rather than a whole. Dismemberment ads leave many women feeling that their entire body is spoiled on account of one less than perfect feature. If a woman has less than satisfactory legs, then her potential for beauty is spoiled. In other words, if every body part is not flawless, then the possibility for beauty is ruined. As previously mentioned, girls and women are conditioned from a young age to view the body as a “work in progress” or something in constant need of alteration. Instead of being satisfied with their body as a whole, they concentrate on what separate entities they lack. Many women compare their bodies and sexuality to the eroticized images that are plastered on billboards and television and in magazines and movies (Kilbourne, 2002).

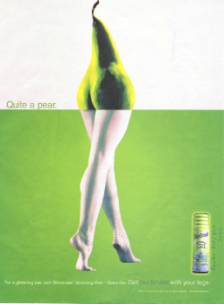

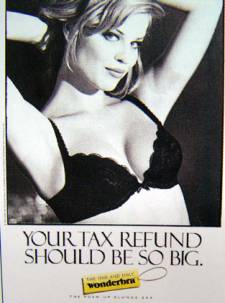

Figure 3: Example of Dismemberment Figure 4: Example of Objectification

The dismemberment of women, in addition to the objectification of women, have serious repercussions including, but not limited to, body shame, appearance anxiety, depression, sexual dysfunction, and eating disorders. The impossible ideal of female beauty saturates our American culture, and reparations are nothing short of dire necessity. Thus, the ambitious goal of this study is to suggest that the dismemberment of women in the media produces negative effects comparable to the negative effects of objectification. In other words, dismemberment is as equally damaging as objectification.

Measuring the Effects of Dismemberment

through the Use of the Objectified Body Consciousness Scale

McKinley and Hyde (1996) developed the Objectified Body Consciousness Scale (OBCS). The OBCS has three components: body surveillance, body shame, and beliefs about appearance control. The first element of the OBCS is body surveillance, the degree to which women view themselves as an object. The feminine body has been constructed as an object to be looked at. This construction encourages women to view their bodies as if they were outside observers. Psychological research has proven that there are negative implications for constant self-surveillance and self-objectification (McKinley & Hyde, 1996; Fredrickson & Noll, 1997; Gettman & Roberts, 2004; Brooks, 1995). The second element of the OBCS is body shame. This encompasses the internalization of cultural beauty standards. Sadly, when women experience internalization, the beauty standards appear to originate from the self, and many women believe that the attainment of these standards is possible, even in the face of considerable evidence to the contrary. The internalization of cultural beauty standards promotes body shame, body dissatisfaction, anxiety, and depression (McKinley & Hyde, 1996). The third element of the OBCS is appearance control beliefs. The OBCS relies heavily on the underlying assumption that women are taught to believe that they are responsible for how they look and have the ability and obligation to alter themselves when necessary. Convincing women that they can achieve the impossible beauty standards of our culture can have very negative effects. There are certainly instances in which a woman has no control over her appearance, and if this is the case, the woman feels like a failure (McKinley &Hyde, 1996).

Thus, it is imperative to conduct research in order to gain knowledge and understanding of the effects of dismemberment advertisements. Future research should employ the use of the OBCS to examine the differences and similarities between objectification effects and dismemberment effects. It is likely that women exposed to dismemberment ads would score just as high, if not higher, on the OBCS, particularly the body shame component and the appearance control beliefs component than women exposed to objectification ads. Recall the history of objectification studies, for there was once a time when objectification was thought to be immeasurable and powerless. Now, after much diligent research, it is evident that objectification is measurable, and objectification does have an impact on women. Further research must be conducted to examine the effects of dismemberment in advertising.

Summary

Undoubtedly, the sexualized portrayal of women in the media has significantly negative outcomes. These negative outcomes are not only affecting adult women but also young girls. Females are buying cosmetics and beauty products at increasingly younger ages. Recently, researchers have begun exploring self-surveillance, body shame, and disordered eating tendencies in preadolescent females and found that girls as young as seven are showing signs of disordered eating and self-surveillance (Good, Mills, Murnen, & Smolak, 2003). The media affects some women in subtle ways (unconsciously), and other women are affected in a more direct way (consciously). The problematic representations of women in the media deserve our immediate attention, consideration, and research. Future studies should include: further exploration of the relational barriers between men and women, the centerfold syndrome and its effect on human intimacy, the appeal of physical sex to women and its relationship to the dismemberment of women in the media, the relationship between dismemberment ads and body shame and body dissatisfaction, the relationship between dismemberment ads and eating disorders, and the relationship between dismemberment ads and depression.

*All images were retrieved from Scott A. Lukas’ Gender Ads Project website: www.genderads.com

*Copyright statement: All rights reserved by the Undergraduate Research Community.

REFERENCES

Baker, D., Sivyer, R., & Towell, T. (1997). Body Image Dissatisfaction and Eating Attitudes in Visually Impaired Women. London: Division of Psychology, University of West Minister.

Brooks, G. (1995). The Centerfold Syndrome: How Men Can Overcome Objectification and Achieve Intimacy With Women. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Fredrickson, B., Noll, S., Roberts, T., Twenge, J., & Quinn, D. (1998). That Swimsuit Becomes You: Sex Differences in Self-Objectification, Restrained Eating, and Math Performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 269-284.

Gettman, J., & Roberts, T. (2004). Mere Exposure: Gender Differences in the Negative Effects of Priming a State of Self-Objectification. Sex Roles, 51, 17-27.

Good, L., Mills, A., Murnen, S., & Smolak, L. (2003). Thin, Sexy Women and Strong, Muscular Men: Grade-School Children’s Responses to Objectified Images of Women and Men. Sex Roles, 49, 427-437.

Kilbourne, J. (2002). Beauty and the Beast of Advertising. Retrieved March 12, 2005 from http://www.medialit.org/reading_room/article40.html.

McKinley, N., & Hyde, J. (1996). The Objectified Body Consciousness Scale: Development and Validation. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 20, 181-215.

Roberts, S., & Fredrickson, B. (1997). Objectification Theory: Toward Understanding Women’s Lived Experiences and Mental Health Risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21, 173-206.

Tiggeman, M., & Kuring, J. (2004). The Role of Objectification in Disordered Eating and Depressed Mood. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 43, 299-311.