Problems of Solid Waste Management in Nima, Accra

Freduah George

University of Ghana, Legon

ABSTRACT

The study sought to identify the problems of solid waste management in Nima. The two broad types of data, the secondary and primary data were used in the study. Interviews and personal observations were also used to collect some of the data. Factors impeding the effective and efficient solid waste management were identified. Wrong attitudes and perceptions of the people about sanitation issues contributed to solid waste management problems of Nima. Majority of the households did not educate their members on the need to clean their surroundings. A greater percentage of the household did not have a toilet facility. Virtually, all the people depended on the Accra Metropolitan Assembly (AMA) facilities for the disposal of their household refuse. Solid waste management problems were partly the results of AMA’s inability to cope with the situation because of lack of equipment and personnel. In addition, lack of proper incentives for the AMA workers working in Nima also partly explained the problem. It was recommended that more education should be provided by the AMA to sensitise the people on the need to keep the surroundings clean.

Introduction

Humanity has always produced waste that included not only the discarded bones of animals slaughtered for food, the hundreds of stone axes found in Olduvai, or the stinking cesspits and hidden heaps of Medieval Europe but the momentous increase in waste that characterises contemporary society, dating from the industrial revolution.

Waste is more easily recognised than defined. Something can become waste when it is no longer useful to the owner or it is used and fails to fulfill its purpose (Gourlay, 1992). Solid waste according to Miller (1988) is any useless, unwanted, or discarded material that is not liquid or gas. A great mixture of substances including fine dust, cinder, metal, glass, paper and cardboard, textiles, putrescible vegetable materials and plastic characterise solid waste (Simmens, 1981).

As time passes the only certainty is that accumulation of waste will outstrip its control. Throughout the western world, there are no longer enough convenient holes in the grounds into which to tip unwanted matter (Gourlay, 1992). The third world, having refused to become the “dustbin” of the western world, also lacks appropriate storage facilities, treatment technologies, and good methods of disposal for its waste.

Not discounting the above factors, other factors might have compounded the problem. People’s apathetic and lackadaisical attitudes towards matters relating to personal hygiene and environmental cleanliness, of which waste management in general is its focal point, should not be over looked.

There is no single solution to the challenge of waste management. The waste management process is usually framed in terms of generation, storage, treatment, and disposal, with transportation inserted between stages as required. Hence, a combination of source reduction, recycling, incineration, and burring in landfills and conversion is currently the optimal way to manage solid waste.

Like other parts of the capital city of Ghana, such as Mamobi, James Town, and Chokor, Nima is engulfed in filth of both conspicuous and inconspicuous places because it has serious problems with its waste management from generation, through storage, treatment, to disposal. Residents’ wrong perceptions and unconcerned attitudes towards waste management might also be the cause of this problem.

It therefore becomes important for this study to examine the problems of solid waste management in Nima. This research is therefore intended to provide insight to citizens, government officials, and business people who might want to help resolve the solid waste management crisis in Nima.

Literature Review

A lot has been said, written, and demonstrated about the inadequacies in solid waste management and its associated problems. According to a United Nations Conference on Human Settlement report, one third to one-half of solid waste generated within most cities in low- and middle-income countries, of which Ghana is no exception, are not collected. They usually end up as illegal dumps on streets, open spaces, and waste lands (UNCHS 1996).

Despite the importance of adequate solid waste management to the urban environment, the performance of many city authorities in this respect leaves much to be desired. According to Malombe (1993), irregular services rendered to producers of refuse by municipal councils compel them to find ways of disposing of refuse. He observed that the main methods adopted by the producers are burning, composting, or indiscriminate dumping.

This is very pertinent in Ghana where waste management services are largely inefficient and ineffective. It is estimated that about 83% of the population dump their refuse in either authorised or unauthorised sites in their neighbourhood, and due to weak capacity to handle solid waste, unsanitary conditions are created (Benneh, Songsore, Nabila, Amuzu, Tutua, & Yaugyuorn, 1993).

Although these weaknesses have been attributed to lack of logistics and financial management, people’s attitudes towards waste management should not be ignored (Nze 1978). He outlined several factors, which have conspired to promote the massive build up of urban garbage and waste. Nze noted that they resulted from inadequate and deficient infrastructure, inadequate structures for environmental administration, lopsided planning pastures and disregard for basic aesthetics, industrial and commercial growth, and other human factors. According to him, urban wastes in Nigeria are regarded as “non resources” having at best a nuisance value and therefore not surprising that an equally negative posture has been adopted in managing wastes from urban concentrations in the country.

Navez-Bounchaire (1993), stated that the management of household refuse is tied to perceptions and socio-cultural practices which result in modes of appropriation of space which are greatly differenced according to whether the space is private or public. This is relevant to the study, because the area has diverse socio-cultural practices, as the population is heterogeneous.

To Sule (1981), the main cause of the problem of Nigerian city’s poor environmental condition can be ascribed to improper management of solid wastes and the lack of seriousness in the enforcement of solid waste disposal code. This is very pertinent in Ghana where the enforcement of the solid waste disposal code is not effective at the local levels.

Karley (1993), in an article entitled, “Solid Waste and Pollution,” in the Daily Graphics (October 9, 1993) identified the main problem facing Ghana as the lack of suitable sites for disposal of solid waste, of which we attribute to the failure of social and economic development to keep pace with the natural population increase and rural-urban migration. This is an undeniable fact, because Nima residential area in Accra is seriously facing that problem due to poor planning, lack of logistics, and poor attitudes towards solid waste handling.

Benneh et al. (1993) observed that residential domestic waste forms the bulk of all sources of solid waste produced in urban areas. These household wastes are known to have high densities with high moisture content and the organic component of solid wastes, which properly accounts for about 70% to 90%, while tins, cans and paper are probably responsible for about 5% to 10% of the total waste produced. They further argued that because the capacity to handle all of the household waste generated is still weak, about 83% of the population dump refuse in either authorised or unauthorised sites in their neighbourhood which creates unsanitary conditions. They also argued that insufficient communal facilities can lead to open defecation along beaches, drains, and open spaces and the tendency for faecal materials to become intermixed with household refuse.

This view expressed by Benneh et al. (1993) is relevant to the study because areas like Nima, Mamobi, and Chockor are densely populated and are low-income areas. They are also not served with adequate sanitary facilities. These inadequacies lead to indiscriminate disposal of refuse into drains, gutters,and waterways, and to open defecation in these areas. Benneh et al. proposed the involvement of local groups in solid waste management side by side the operations of governmental agencies.

According to Stirrup (1965), the method of refuse disposal must be related to the nature of the community served, its financial capacity, the type of materials arsing, climatic conditions, the desirability of utilising materials in certain instances compared with the imperative need to utilise them in order to assist in the provision of vital raw materials. The effectiveness of the selected system will be determined in relation to the immediate disposal requirements and the need to cater to the conditions likely to arise from planned future developments in the area.

According to Songsore (1992), solid waste management has remained one of the intractable problems with the Accra Metropolitan Assembly (AMA). His argument supports the fact that waste producers generate large volumes of wastes but do not dispose of waste in an acceptable manner. This is important to the study because people’s attitudes towards waste management are questionable. With the establishment of the Waste Management Department (WMD) of Metropolitan and Municipal Assemblies, the public tends to have the view that the departments should be solely responsible for managing wastes. He further observed that indiscriminate disposal of waste has resulted in the clogging of the few built drainage channels and natural watercourses with garbage and silt, which are not removed regularly. This argument is not peculiar to AMA alone, the problem reflects the situation in most urban areas. The city of Accra for instance has been engulfed in refuse, with drains and gutters mostly choked with rubbish.

Edmunson (1981), in his study on refuse management in Kumasi, pointed out that most sites used for refuse dump are chosen without taking into consideration the distance to be covered by residents. Thus, he recommended that sanitary sites should be cited close to waste generators. Adelaide (1995) also observed that disposal sites in Accra are situated quite a distance away from inhabitants or sellers. Thus, one cannot dispute the fact that long distance disposal sites discourage inhabitants and sellers from making use of them. They therefore resort to littering their surroundings. This might be a factor in the poor sanitation in Nima. He also argues that inhabitants, sellers, shoppers, and industrialists dispose of waste on the street, into troughs, and at other unauthorised places. He attributes these unacceptable habits of indiscriminately disposing of waste to the public’s lack of waste disposal culture as well as inadequacy of waste disposal facilities. This testifies to the importance of attitude in waste management issues.

Furthermore, Cotton and Ali (1993) found that a major obstacle to the provision of latrines in some urban areas is the small size of the plot allocated for the purpose. They observed that lack of knowledge on the part of householders, unaffordability of household toilets, and several other factors are the main cause of lack of household latrines. This is not different in Ghanaian context, where most of the low-income settlements in the urban centres are unplanned. The study of Asamoah (1998) revealed that lack of adequate sanitary facilities results in indiscriminate dumping of refuse and defecation at places not designated for such purposes. He suggested that big containers should be provided at specific intervals in the Kumasi Metropolis.

Abrokwah (1998) observed that ignorance, negligence, lack of law to punish sanitary offenders, and low level of technology in waste management are the major causes of waste management problems in Kumasi. Accra is no different from these observations. He suggested that awareness should be created among residents to manage household refuse and educate them on the hazards that ill-disposed waste could pose to the environment and to themselves.

According to Agbola (1993), cultural derivatives, beliefs, perceptions and attitudes are learned response sets. They can therefore be modified or changed through education. This points to the fact that people’s unconcerned attitudes towards solid waste can be changed for the better through education. According to Pacey (1990), formal education for women is a pre-requisite for change in sanitation behaviour.

Abankwa (1998) found that households of high income and single dwelling units generate an average dry refuse of three kilograms per day, while the low income and compound dwelling units generate about five kilograms. Of the five kilograms of refuse in the low income units, garbage constitutes four point two five kilograms, and rubbish constitutes zero point five kilograms. The wastes invariably consist of items like vegetables and tuber remains. This is relevant to the study for the fact that the area is a low-income settlement.

This high generation of waste tells us how source reduction as a waste management method is important. Gourlay (1992) argued that by focusing on the production process itself, examining where wastes are generated, and exploring how they can be reduced, even simple measures, such as separating wastes so that they can be reused more easily, using different raw materials or replacing non-biodegradable products with biodegradable ones, can help achieve large waste reduction results. He also claimed that the greater part of present waste arises not because the producer does not want it, but he fails to use it, or at least use it in such quantities that waste is inevitable. This argument places emphasis on recycling and conversion of waste as important solid waste management practices.

According to Stirrup (1965), pulverization and grinding are means of reducing the volume of waste, or they are used to prepare refuse for final disposal processes. He further stressed that in some instances a threefold problem could be overcome by the use of composting. Thus, the feeding of impoverished soils, disposal of large portions of the refuse, and the disposal of sewage sludge can be realised through composting. Moreover, Stirrup claimed that the major advantage of incineration are complete destruction of combustible and organic matter, reduction of bulk, the ability to operate under hygienic conditions free from interference by the type of weather conditions that would affect disposal by tipping and the possibility of using residual heat from the furnaces. The solid waste management system of Ghana, and for that matter Accra, lacks most of these advantages due to the inability to afford incinerators. Gourlay (1992) observed that in larger cities, collection and disposal of solid waste is a municipal responsibility but the actual business of disposal is often contracted out to private firms.

Problem Statement

Despite the present concerns of individuals and the government about waste management in Ghana, Nima, one of the many suburbs of Accra, is still faced with serious solid waste management problems. From observation, domestic and municipal solid wastes are commonly found in Nima. Domestic waste comes from activities such as cooking and from human excreta. Municipal wastes are the trash from commercial establishments, small industries, and households. These include tins, plastic products, and polythene bags. These form the greater part of the waste observed on the streets, in gutters, and the back of houses in Nima.

Containers for storing solid wastes in homes include old buckets, baskets, plastic containers, boxes, sacks, and even polythene bags, which in most cases have no lids. Hence, the wastes are even spread around before they get to the sanitary sites. Solid waste, when treated well, can be turned into a resource, but the greater part of wastes generated in Nima seem not to undergo any treatment before their final disposal. They are left in piles for weeks to create unsanitary scenes that smell bad and, worst of all, create diseases. Solid wastes generated in Nima are most often disposed of in open dumps, gutters, and at the back of houses probably due to the inadequate solid waste management equipment or the long distances to the sanitary sites. People also leave their wastes in piles for days before they finally get to the sanitary sites for disposal.

The above problems make it clear that the Municipal Assembly is unable to cope with the problem. On the bases of the above problems, the study has the following objectives:

Objectives

- To ascertain the attitudes and perceptions of people towards solid waste management.

- To assess solid waste management both at the household levels and by AMA as well as the personnel status of AMA in handling solid waste in the study area.

- To assess the kind of incentives available for the AMA workers dealing with solid waste.

- To make recommendations for improving solid waste management in the study area.

Propositions

- The people’s poor attitude and perceptions about solid waste management have contributed to the problem.

- Inadequacy and inefficiency of solid waste management equipment and personnel are also contributing factors to the problems of solid waste management.

Instruments

The primary data were collected using structured questionnaires. The questionnaires contained both closed and open-ended questions, and they were self-administered. In all, 70 questionnaires were administered to households.

Secondary data were collected from appropriate data sources, including books, journals, newspapers, and activities both published and unpublished.

Fifty-five (55) females and 15 males were interviewed. This distribution was used because it is observed that the females, mostly mothers, are responsible for domestic waste handling. Again, solid waste production is at the household level.

The authorities of the AMA were also interviewed. Personal interviews and observations were conducted to obtain more information.

In order to assess whether or not people’s attitudes and perceptions have relationships with their level of education, 20 people without formal education were interviewed, and the other 50 people interviewed had some level of education (elementary, junior secondary school level, senior secondary school level, and tertiary level education).

The data gathered from various sources were processed and analysed. Simple descriptive statistical and analytical tools such as frequencies, percentages, and pie charts were employed in the analysis of the data. Relationships were established by cross tabulations.

Geographical and Historical Background of the Study Area

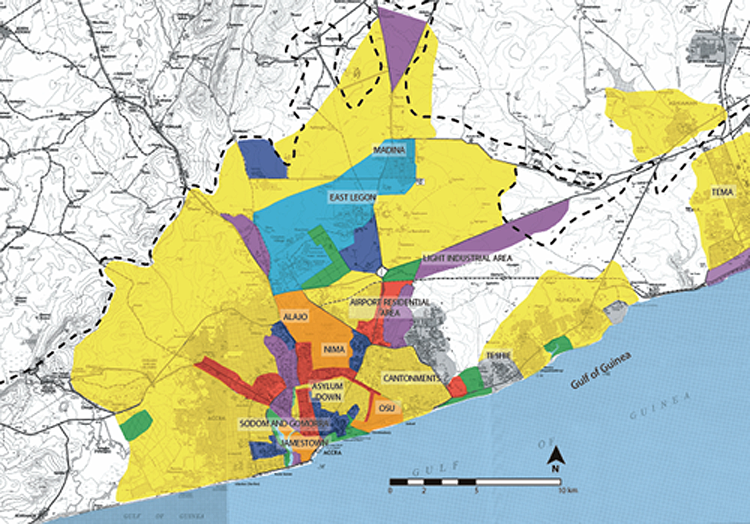

Location and Size. Nima is located to the northeast of Accra city centre and about four miles away from it (see Figure 1). It extends over an area of about 351.6 acres of sloping ground. Its longitudinal boundaries are between 0°11.5” east and 0°12.20” west. Latitudinally, it is between 5°35” north and 5°34” south. It is bounded in the west by Mamobi, east by Kanda, north by Kokomlemle. and south by Accra New Town.

Historical Perspective. Nima is an Arabic word which means, “strangers’ resting place” and first applied to the area settled by Alhaji Amadu Futa (Malam Futa) in 1931. This community grew up essentially as a zongo. The growth of Nima stemmed largely from the result of the rapid urbanisation of Accra. As the population of Accra began to increase, the migration quarters like Adabraka, Tudu, and especially Zongo Lane began to be packed with newcomers from the rural areas and from neighbouring countries who came to the capital in search of job opportunities.

Alhaji Futa’s house at Zongo Lane in the heart of Accra became one of the homes for the city strangers. The Alhaji was a prominent cattle dealer and Muslim teacher, which made him a man of high status in the Muslim community. Muslim norms of hospitality require people of such social significance to receive strangers and give them the necessary assistance either in locating their relatives or in overcoming their immediate problems. The Alhaji’s house therefore attracted many strangers. As a result, the number of his guests increased and this led to a shortage of accommodations in his compound. The solution to this problem was therefore to go out of the city centre.

According to historical records, the site of Nima had been the Alhaji’s cattle grazing grounds, where he had previously built one or two mud huts for his Hausa/Fulani cattle heard. He then formally obtained permission from the Odukpong family at Osu and Gbese people at Accra (the customary owners of the land) to settle there. Thus, the community of Nima grew out of Alhaji Futa’s compound.

The area’s growth began to attract other people both from the city centre and also new migrants into the city who came to find accommodation or stay with relatives or friends while seeking jobs. The area further expanded with the establishment of the American Military base northeast of Nima, Cantonments, and Airport Residential areas. These areas were expanded to house the increasing number of British and American military and service personnel who came into the country. These areas characterised by the large number of African population created a demand of diverse forms of semi-skilled labour. Thus, Nima then outside the municipal boundary by virtue of its proximity to these sources of employment become an attractive residential place from the inner city. These people came to provide services to the expatriate officials as cooks, stewards, labourers, porters, prostitutes, and the like. Hence, Nima’s growth in population and size is largely due to urbanisation and rural-urban migration.

Physical Environment. Currently, Nima faces all the serious problems confronting all rapidly growing areas. Sanitation generally in the area is very poor. There are visible unsightly scenes of heaps of rubbish in containers, which are ever flowing. Livestock are often found feeding on some of the rubbish on or along the streets and other open places.

The area has a very poor drainage system. Drains, which are very essential in residential areas, are lacking in the area. The very well constructed ones along roads are in a deplorable state with most of them caving in. These drains are dirty and filled with rubbish, and some are running through compounds of houses.

Basically, there is a minimal provision of amenities such as adequate refuse dumping grounds, toilet facilities, and playing fields as well as recreational centres for the area. There is evidence of uncontrolled development. This and the lack of basic infrastructure have made the community substandard. In terms of residential stress, it is one of the worst affected areas in the Greater Accra Metropolitan Area. The houses are invariably of the closed compound courtyard type. On the whole, the general environment is quiet dismal, and it especially faces very severe problem of solid waste management.

Economic Background. The occupational background of the residents is mainly trading for the women and civil service for the men. Most of the women engage in marketing activities. A few of the women are also engaged in palm-kernel oil extraction. The majority of men work as civil servants, “Watchmen” (security men) and labourers. Only a small proportion and insignificant percentage of the population work as office employees, and most of this category have a fairly high standard of living and higher educational background. A few of this category work as civil servants with the majority in the private sector.

The occupational level of residents is closely linked up with their income level. Various surveys showed that most of those who work as low level civil servants (“watchmen” and labourers) receive between ¢100,000 and ¢200,000 a month. These residents no doubt finds it difficult to make ends-meet as most of them have large families and in most cases have no formal education.

Very often, it is the income generated by the trading women that is used to support the income of their husbands and for that matter the up-keep of the family. Most of the women traders are able to earn more than their husbands who work as low-level civil servants, and in most cases the financial support from the women in the family is higher than that of the men. Income levels in Nima are generally low as majority of the residents have low formal educational backgrounds.

Religious Background. The major religions practiced by the residents of Nima are Islam, Christianity, and Traditional religion.

Islam is the dominant religious practice as it is prevalent in almost all the sub-areas. It is in most cases the Hausas and Northern tribes who constitute the bulk of the Muslim population.

Christianity is the second dominant religion in Nima. In most cases the Akans, Ewes, and Gas form the greater part of the Christian population.

The traditional believers are found dotted in almost all the sub-areas. The main traditional believers are the Gas and Ewes.

Figure: 1 Map of Accra Showing the Study Area.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Attitudes and Perceptions of the People towards Solid Waste Management

Issues of attitudes and perceptions appear to affect both inhabitants and authorities regarding solid waste management in Nima. Issues such as people’s opinion on responsibilities for ensuring clean surroundings, education of household to clean their surrounding, disposal of household waste, and children’s involvement in solid waste management are described below.

Table 1: Opinions on Responsibility for Ensuring Clean Surroundings

Source: Field Survey 2004

Response

Frequency

Percentage

AMA

53

75.7

Individuals

7

10.0

Both AMA & Individuals

10

14.3

Total

70

100.0

With a large percentage of the population thinking that AMA is solely responsible for ensuring clean surroundings, it is likely that the people may not support clean up campaigns meant for making the surroundings clean. This may partly explain why Nima is engulfed in filth and yet the respondents seem unconcerned. This confirms the studies of Songsore (1992) that with the establishment of the Waste Management Department (WMD) of Metropolitan and Municipal Assemblies, the public tend to have the view that the WMD should be solely responsible for managing waste.

In order to change this trend it is suggested that the people be educated to see the problem as a shared responsibility of both the individual in the respective communities and the AMA. Further analysis of the data showed that about 37% of the total respondents thought it was appropriate for individuals to share in the responsibility of cleaning their own surrounding while about 63% thought it was not appropriate. The 37% respondents who thought individuals must be responsible for cleaning their own surroundings gave their reasons as indicated in Table 2 below.

Table 2: Reasons for Individuals to Help Clean their Own Surroundings

Source: Field Survey 2004 * Multiple response

Response

Frequency

Percentage*

The residents are mostly affected by the bad odour resulting from dirty surroundings

49

40.5

Dirty surroundings cause diseases

53

43.8

It will save the individuals some money

19

15.7

Others

?

Total

121

100

Besides the above reasons given by the respondents that individuals should take responsibility for the cleanliness of their surroundings, there are others reasons. These reasons include the impressions of visitors to the area, destruction of the area’s scenic beauty, and the choking of drainage channels that will lead to flooding and environmental pollutions.

The responses suggest the lower level of the respondents’ knowledge concerning sanitation issues. More seminars and talk shows on sanitation could be organised by the government or organisations as a remedy. It was realised that there was some kind of relationship between the respondents’ level of education and their perceptions about cleaning their own surroundings. A higher percent of those with relatively higher education thought it was appropriate for individuals to clean their own surroundings. This confirms the findings of Pacey (1990) that formal education for women in particular is a prerequisite for change in sanitation behaviour. A summary of these findings is shown in Table 3 below.

Source: Field Survey 2004

Levels of Education

Response (%)

Tertiary

100

Senior Secondary School

80

Junior Secondary School

53

Elementary/Primary

14

Nil

5

From this analysis, the problem of solid waste management and people’s attitude and perceptions in the study area can be linked to the levels of formal education. Improved teaching and learning of issues on sanitation in all levels of education could help improve the general sanitation in the communities.

This supports the suggestion of Agbola (1993) that perceptions and attitudes are learned response sets and can therefore be modified or changed through education. Hence, continuous public education of the people of Nima may help improve the sanitation in the Area. Education of households on cleaning their surroundings was discussed. The causes of many nations’ environmental problems could be found by the way the imbedded behavioural patterns and acquired values are superimposed on the environment. The imbedded behavioural patterns are cultural in origin, derived from the socialising processes in families and communities (Agbola, 1993: 24).

The study showed that as high as about 74% of the respondents do not educate their households on the need to clean the surroundings while about 26% do. The implications of having more people who do not care to educate their household on making their surroundings clean could mean that the society will translate it into acceptable behaviour in relation to solid management, and especially the children will not develop the right perceptions and attitudes for sanitation at an early stage in life. This is likely to impact negatively on how the next generation would handle sanitation in general and solid waste in particular. Behavioural patterns as suggested by Agbola (1993) are derived from the socialisation process in the families and communities.

The perpetual creation of the awareness on the need for household heads and well informed members to educate their household on basic issues on sanitation may help curb the problem. Linked to the interest of the households, educating other members is the lesson that should be taught. For the few (25%) that educated their households on sanitation, some of the lesson taught are summarised in Table 4 below.

Table 4: Lessons Taught to Household Members on Sanitation

Lessons

Frequency

(1) Dirty surroundings cause diseases

20

(2) House members must not litter

10

(3) People and family must not defecate at unauthorised places

12

Both (1) and (2)

15

Both (1) and (3)

18

Both (2) and (3)

19

Total

94

Lessons such as the regular organisation of communal cleanup exercises, discouraging of people who may be found littering about and respect for sanitary laws did not come up as issues taught. The respondents’ inability to point out these lessons could be an indication that general education on sanitation should be further emphasised in the community.

It was observed from the survey that people relied heavily on AMA facilities for their refuse disposal. None of the respondents depended on private contractors. The situation as presented above partly explains why the AMA is unable to cope with the problems of solid waste management in the study area. As every household looks up to the AMA for its solid waste disposal, it puts unmanageable pressure on the equipment and insufficient work force, among other things.

The study further showed that about 86% of the respondents involved children below the age of ten in the disposal of their household waste. Such children are often asked by their parents and other family members to carry household refuse to the sanitary sites for disposal. About 50% of the respondents who involved such children in solid waste disposal claimed it was children’s responsibility to carry the household waste to the sanitary site. Thus, according to these respondents carrying of household waste was not the duty of adults.

About 14% of the respondents who did not involve such children in solid waste disposal explained that they did not have such children in their household to carry refuse. There is a greater likelihood of indiscriminate disposal of household waste in Nima with children dominating as carriers of household waste to the designated sanitary sites. This may partly explain why refuse is found all over Nima. Plate 1 shows the indiscriminate disposal of household waste in some parts of the study area.

Plate 1 : A drain filled with rubbish in parts of Nima. Diseases are likely to affect most People with its attendant cost on the economy

This problem might be changed for the better if the children (under ten) who carry household waste are given special training about solid waste handling.

The study indicated that the respondents used containers like sacks, plastic containers, baskets, old buckets, polythene bags and dustbins to store solid waste. Table 5 shows the above distribution.

Table 5: Household Solid Waste Storage Containers

Containers

Number

Percentage

Sack 24

34.3

Plastic Containers 20

28.6

Baskets 9

12.8

Old Buckets 7

10.0

Polyth ene Bags 6

8.5

Dustbins 4

5.7

Total

70

100.0

Source: Field Survey 2004

With the exception of the dustbins, none of the containers had covers (personal observation). A substantial percentage of the garbage is put into polythene bags before kept in the storage containers. These waste handling methods are a likely contributory factor for poor sanitation in the area, because much of the refuse is littered about before reaching the sanitary sites.

Generally, it was realised that a greater percentage of the respondents relied on sacks than other storage methods. This might be because it was cheaper and perhaps could store more waste but lack of any covers have serious health implications. Most of the refuse is kept close to kitchens and rooms, which may cause diseases like cholera and typhoid fever. The AMA subsidising the prices of standard dustbins and offering education to residents on the need to store refuse in dustbins could help change this situation for the better

Distribution of Toilet Facilities in Households

The study showed that about 67% of the respondents had no toilet facilities in their houses, about 20 % had pan latrines, 7% per cent had Kumasi ventilated improved pit (KVIP), and about 6% had water closet (WC). From the survey, all the respondents without a toilet facility in their houses used the public toilet. The KVIP latrine is the most widely used type of public toilet (personal interview).

Having greater percentage of respondents using the public toilet might suggest that closure of public toilet facility due to its overuse might deny a greater number of people access to human excreta disposal facility. This might be one of the major causes or indiscriminate defecation into drains and opens spaces in the area. From interviews, respondents identified long queues as a major problem encountered in the use of public toilet facilities in the area.

The 20% of respondents with pan latrine toilet facilities in their houses complained that it easily got full and dislodging had become a problem. Landlords found it difficult to get personnel to empty the pan when it is full (Alhaji Adamu, personal communication). In order to control the afore discussed problems, it is suggested that bylaws must be enacted requiring every household to build an environmental and health hazard-free toilet facilities.

Role of AMA in Solid Waste Management

Generally, all solid wastes produced in Nima are collected for final disposal at various designated sanitary sites by the WMD of the AMA. This is because Nima is a third class residential area with low-income status, poor layout of lanes, poor roads and other infrastructure, and dense population. Unlike the high-income areas such as Dzorwulu and Airport residential areas, the expensive door-to-door system of solid waste collection cannot be practiced in Nima.

This confirms the studies conducted by Stirrup (1965), that the waste management method adopted must be related to the nature of the community served, its financial capacity, and climatic conditions. The WMD is not able to cope with the solid waste management problems in the area as the amount of waste produced far out weighs its capacity to dispose of it (WMD, East Ayawaso Sub-Metropolitan Assembly of AMA). This is because of its inadequate equipment, which is also a result of limited finances and lack of modern equipment and personnel.

These problems coupled with the attitudinal and perceptual problems even exacerbate the problem. A summary of the kind and adequacy of AMA’s equipment is shown in Table 6 below.

Table 6: Types and Numbers of Equipment for Solid Waste Management by AMA

Description

Available

Optimum Required

Power Tiller

1

4

Refuse Trucks

5

9

Compaction Trucks

3

6

Roll Ons

2

4

Containers

16

23

Sanitary Sites

10

17

Wheel Barrows

18

50

Shovel

20

100

Rakes

16

100

Forks

20

100

Pick Axes

10

20

Brushes

100

200

Underground Holding Tanks

4

0

Wallington Boots

20

100

Hand Gloves

50

200

Source: WMD, East Ayawaso Sub-Metropolitan Assembly of AMA

Analysis of the data gathered from the AMA, indicates that there were 10 sanitary sites but these were woefully inadequate. An ideal number of 17 sites were required by the AMA.

The major problem arising at this point is that it is even impossible to create new sanitary sites. This is because designed sanitary sites have been encroached upon by some recalcitrant residents. Consequently, the whole area is well packed with houses and other unauthorised structures and has no available unused space.

The bigger problem facing the department has to do with finance. The government has greatly cut down its subversion to the WMD. As a result, the department is unable to afford enough and better equipment as indicated in the previous figure (WMD).

The number of workers at hand on the field was known from the WMD to be practically inadequate. More people need to be employed but the department was unable to do so because of its financial problems. A summary of the finding is shown in Table 7 below shows the inadequacy of the labour force.

Table 7: The Labour Force of WMD

Source: WMD, East Ayawaso Sub-Metropolitan Assembly of AMA

Labour Description

Available Number

Optimum Number

Scavengers (Men)

25

80

Sweepers (Women)

31

120

Refuse Labourers

100

250

Cleaning Officers

40

65

Clearing guards

74

98

Because the WMD is unable to provide enough vehicles, containers, and personnel, more waste continues to pile up for weeks in most sanitary sites before the final disposal is carried out. This confirms the argument that the process of waste management is usually framed in terms of generation, storage, treatment, and disposal, with transportation inserted between stages as required (Gourlay 1992).

This problem has encouraged the use of various inappropriate methods for household waste disposal such as wastes being left in the open in pits and open burning of the waste. The help of concerned citizens, governmental organisations, and nongovernmental organisations in terms of the provision of funds and equipment may be a remedy to this problem.

Data from the WMD of AMA indicates that some levelling and compaction of the solid wastes are carried out as well as some spraying to check the proliferation of flies before the wastes are finally disposed of in the landfill. Notwithstanding, there is no more space at the Oblogo landfill site for refuse disposal. Consequently, the WMD of AMA was required to vacate the Oblogo landfill site by July 2004 (WMD of AMA).

As an effort to mitigate the problem in the forgoing paragraphs, the AMA has on its development plan, better waste disposal methods such as Ultra modern incineration, recycling, conversion into energy (electricity, fuel, gas, etc.) and source reduction. As the distance between saying and doing has always been long, these beautiful plans are still on paper because of the AMA’s financial predicaments. Since the WMD is unable to provide enough equipment, personnel, and better disposal methods, more and more waste continues to heap up in most parts of Nima and the Whole city.

Incentives Available for WMD Workers Dealing With Solid Waste in Nima

Humans are known to work better under certain favourable conditions or incentives. The WMD complained that working in Nima was not interesting at all since most residents were hostile and sometimes would even beat up solid waste workers as a result of the slightest misunderstanding.

This problem is the reflection of the data collected on the field, which showed that about 69% of the respondents did not see the work of the AMA to be important in the area while about 29% saw their work to be important. With such a problem at hand, WMD workers did not work to their full capacity in the area. This partly may explain why Nima is seriously engulfed in filth.

Further analysis of the data revealed that working in Nima was very exacting where the majority of the residents would leave every aspect of the solid waste management to the WMD of AMA. Meanwhile the by-laws on solid waste management did not say so (WMD of AMA). This confirms the results obtained on the field, which revealed that about 67% of the respondents would offer no possible assistance for solid waste management in the area while about 34% said otherwise.

The afore recognised problems coupled with the inadequacy of solid waste management equipment in Nima suggest that there is virtually no incentives that encourage workers in the area. This may partly explain why Nima is notorious for solid waste management problems. Continuous public education of the people and good funding of the WMD may be better solutions to the lack of incentives in Nima.

SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Summary

This study has been concerned with the problems of solid waste management in Nima. The study’s findings were as follows:

- People of the study area had poor attitudes and perceptions toward solid waste handling. They would store their household refuse in substandard refuse containers such as old buckets, sacks, baskets, polythene bags, and boxes that had no coverings.

- The people lacked household toilet facilities. The majority of them depended heavily on public toilets with associated problems such as joining long queues to use the facilities.

- The people depended virtually on the AMA’s facilities for their household refuse disposal.

- The WMD of AMA’s equipment and personnel for handling solid waste in the area were woefully inadequate.

- There were virtually no incentives for workers who dealt with solid waste in Nima. Sometimes, workers were even beaten up on the field. The greater percentage of the people were not prepared to help the WMD workers in any possible way to enable them carry out their work in the study area.

Recommendations

Based on the findings of the study, the following recommendations are made.

- The public should be educated by the AMA on solid waste and its related issues. Basically, hygiene practices should be taught especially on radios, televisions, in news papers, and in schools to educate people on proper ways of handling solid waste and keeping the surrounding clean.

- Stricter enforcement of byelaws should be ensured by the AMA where administrative penalties for minor violations should be taken with urgency.

- The byelaws on sanitation should be made to require every landlord to provide an environmentally friendly toilet facility in his house.

- The AMA should make it a responsibility of introducing the use of standard bins with lid for domestic and commercial use to the people of Nima.

- People should develop proper attitudes and perception towards waste handling, which should be achieved through both formal and informal education.

- The government, donor countries, Nongovernmental Organisations (NGO) and other stakeholders should be encouraged to donate money and equipment to the WMD to enable the department acquire effective and efficient personnel and equipment.

- Worker dealing with solid waste in Nima should be residents of the area. With this, they would be more responsible for their job and be comfortable with the people.

- The community should adopt a self-help approach to solve the problem. Much can be achieved when the various communities mobilise themselves and organise periodic clean up exercises and by contributing financially to support the exercise, the residents can also act as watch dogs and make sure that they themselves adhere to proper waste disposal practices.

- The chiefs and other opinion leaders must be given additional roles to play in ensuring environmental cleanliness. This can be done by authorising the chiefs in each area or community to take up the additional job of ensuring clean environmental practices with the youth playing an important role.

- The women should be made to play an important role as it has been realised that women do a greater part of solid waste handling and disposal in the community.

It is hoped that these recommendations, when considered for action by the government, local authorities, and the people themselves would help address the solid waste management problems and its related issues in Nima.

References

Abankwa, B. 1998. “The problems of Waste Management in Atonsu-Agogo, Kumasi”. Status Report on Population, human Resource and Development planning and policy in Ghana 1960, 1991. National population council, Ashanti Press, Kumasi.

Abrokwah, K. 1998. “Refuse Management problems in central Kumasi”. Status Report on Population, human Resource and Development planning and policy in Ghana 1960 to 1991. National population council, Ashanti Press, Kumasi

Adamu, Personal communication, House number E180/4, Nima - Accra.

Adelaide, A. 1995. Waste Management and Sanitation at James Town and Accra Central. A dissertation submitted to the Department of Sociology, University of Ghana, Legon.

Agbola, T. 1993 “Environmental education in Nigerian schools”. In Filho W.L. (ed) Environmental Education in the Commonwealth, the Commonwealth of learning, Vancouver.

Benneh, G., Songsore, J., Nabila S.J. Amuzu A.T., Tutu K.A, Yaugyuorn 1993 Environmental problem and urban household In Greater Accra Metropolitan Area (GAMA). M.A.C. Stockholm, Ghana.

Cotton A., Ali M. 1993. “Informal Sector waste recycling”. 19 thWater, Sanitation, environment and development Conference Preprints, Ghana.

Edmunson R. 1981, “Refuse Management in Kumasi” Land administration research Centre Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and technology, Kumasi.

Gourlay K.A. 1992. World of Waste, Dilemmas of industrial development, Zed Books Limited, London.

Karley, N.A. 1993. “Solid Waste and Pollution” People’s daily graphic October 9, 1993, pp.5.

Malombe J.M. 1993. “Sanitation and Solid Waste Disposal in Malindi, Kenya. 19 thWater, Sanitation, environment and development conference preprints, Ghana.

Monney J.G. 1987. Perspective of Waste Management in Ghana, Recycling Option Seminar on Abfall, Borse Stock Exchange for Industrial Waste, Geoth Institute, Accra.

Navez-Bouchaive, F. 1993. Cleanliness and the appropriation of space, refuse and living habits in large Moroccan towns, People’s Mediterranean, Morocco.

Nze, F.C. 1978. “Managing Urban Waste in Nigeria for Social and economic development” Journal of Management Studies, Lagos Vol 5, Nigeria.

Pacey, A. 1990. “Hygiene and Literacy”, in Kerr, C(ed), Community Health and Sanitation, Intermediate Technology Publications, Nigeria.

Songsore, J. 1970, Review of Household and Environmental Problems in Accra Metropolitan Area, Accra.

Stirrup, F.C. 1965. Public Cleansing, refuse disposal, Percamon Press, Oxford.

Sule, O.R.A 1981. “Management of Solid Wastes in Nigeria towards a Sanitary Urban Environment”. Quarterly journal of Administration, Lagos vol. 15, Nigeria.

UNCHS. 1996. “An urbanising world global reports on human settlements”, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Department of Geography and Resource Development

University of Ghana, LegonThis questionnaire is designed for a research on problems of solid waste management in Nima. The answers provided therefore shall be treated confidentially.

SECTION A: BIO DATA

1. Gender:

a. Male b. Female

2. Age:

a. Less than 17 years b. more than 17 years.

3. Educational background.

a. No formal education

b. Elementary/primary education

c. Junior Secondary School (JSS)

d. Senior Secondary School (SSS)/Ordinary Level

e. Others: ……………………………………………………………………………………

SECTION B: ATTITUDES AND PERCEPTIONS OF PEOPLE

4. Whose responsibility is it to clean the surroundings?

a. The individuals b. The AMA c. Both

5. Do you think it is appropriate for individuals to clean their own surroundings?

a. Yes b. No

6. Explain your answer: ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

7. Do you often take the chance to educate your household on the need to keep the surroundings clean?

a. Yes b. No

8. If yes, what are some of the lessons you teach them? ……………………………………………………………………………………………………

9. How do you dispose of your refuse?

a. The use of AMA facilities and services.

b. The use of private contractors.

c. Dumping in nearby bushes.

d. Others: ………………………………………………………………………………

10. Do you involve children less than ten years in the household solid waste disposal?

a. Yes b. No

11. If Yes, why? ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

12. Do you have a toilet facility in your house?

a. Yes b. No

13. If no, what kind of toilet facility do use?

a. The public toilet

b. Nearby bushes

c. Others: ……………………………………………………………………………………

SECTION C: KIND AND ADEQUACY OF FACILITIES AT THE HOUSEHOLD LEVEL

14. Check if applicable.

STORAGE FACILITY

TOILET FACILITY

a. Dustbins

a. Water Closet (W.C)

b. Others

b. Pan latrine

c. Others

d. No toilet facility

SECTION D: INCENTIVES

15. Do you see the work of the waste management personnel to be very important in Nima?

a. Yes b. No

16. Would you offer any possible assistance for solid waste management?

a. Yes b. No

SECTION E: SUGGESTIONS

17. What are your suggestions for proper solid waste management in Nima?

………………………………………………………………………………………………

………………………………………………………………………………………………

………………………………………………………………………………………………

APPENDIX B

Department of Geography and Resource Development

University of Ghana, LegonQUESTIONNAIRE FOR THE AMA

This questionnaire is designed for a research on the problems of solid waste management in Nima. The answers provided therefore shall be treated confidentially.

SECTION A: KIND ADEQUACY OF EQUIPMENT AND PERSONNEL

1.

Equipment

Available Number

Optimum Number

2.

Description Of Labour

Available Number

Optimum Number

SECTION B: INCENTIVES

3. Do you feel comfortable working in Nima?

a. Yes b. No

4. If no, why? ……………………………………………………………………………………

SECTION C: PLANS FOR SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT

5. How does the department treat the solid waste?

a. Composting

b. Converting into energy (electricity, fuel, gas, etc.)

c. Recycling

d. Others: ……………………………………………………………………………………

6. How often do you use each of these methods and on what scale?

………………………………………………………………………………………………

………………………………………………………………………………………………

7. Which of the following disposal methods do you use?

a. Incineration

b. Land disposal

c. Recycling

d. Others: ……………………………………………………………………………………

8. What are some of the problems resulting from these methods?

…………………………………………………………………………………………………

…………………………………………………………………………………………………

9. What are some of the greatest difficulties you encounter working in Nima?

…………………………………………………………………………………………………

10. What do you intend doing about these difficulties?

…………………………………………………………………………………………………

…………………………………………………………………………………………………

…………………………………………………………………………………………………

…………………………………………………………………………………………………

|