Understanding Ethnic Disparities in Contraceptive Use:

The Mediating Role of Attitudes

Sarah K. Christman

Tina Zawacki*

University of Texas at San Antonio

Abstract

The purpose of the current study was to investigate ethnic differences in contraceptive use and investigate variables that may explain these differences. An ethnically diverse sample of female college students completed a 15-minute survey that included scales measuring contraceptive use and pregnancy, contraceptive, and sexual attitudes. Compared to non-Latina participants, Latina participants reported lower rates of contraceptive use. Mediation analyses found that the ethnic differences in contraceptive use were partially explained by ethnic differences in comfort with sexual communication and perceived convenience of contraception. These findings hold implications for improving unintended pregnancy prevention programs.

Introduction

According to the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), in 2001 in the United States, nearly half of all pregnancies were unintended (Finer & Henshaw, 2006). Healthy People 2010 set the goal that by 2010 only 30 percent of pregnancies would be unintended. Unintended pregnancies that are continued to term are associated with an increased risk of detrimental prenatal parental behaviors, such as smoking and drinking, and often times lead to negative health and social outcomes for both the mother and the child. The rate of unintended pregnancy in 2001 was substantially above average among women aged 18–24, unmarried (particularly cohabiting) women, low-income women, women who had not completed high school, and minority women (Finer & Henshaw, 2006). Efforts to decrease unintended pregnancy in the United States include finding better forms of contraception, increasing contraceptive use and adherence, and helping people comprehend the multiple dimensions of unintended pregnancy, which will hopefully lead to a better understanding of the consequences of these pregnancies (Santelli et al., 2003).

Past research has shown that there are large ethnic differences in unintended pregnancy and birth rates, with Latina women having the highest rates in the nation for almost all age groups (Chandra, Martinez, Mosher, Abma, & Jones, 2005). The Latino community is growing quickly in the United States and is considered an at risk group for unintended pregnancy and high birth rates. Therefore, it is important for research to focus on ways to increase pregnancy planning and contraceptive use in this group. Investigating ethnic disparities in unintended pregnancy and birth rates as well as contraceptive use, may help policy makers and public health professionals identify high-risk groups of women and thus provide them with the means needed to achieve their reproductive goals (Finer & Henshaw, 2006).

A variety of factors have been found to influence contraceptive use. Deardorf, Tschann, and Flores (2008) suggest there are specific sexual values that may play important roles in contraceptive use. These sexual values include level of comfort with sexual communication as well as level of sexual comfort and sexual self-acceptance. Marin (2003) found that Latino adults, particularly women, reported that communicating about sex often causes discomfort and is perceived as inappropriate and that, in turn, Latino men are expected to respect women by not discussing sex. Such lack of communication about sexual issues has the potential to lead to negative outcomes, including low rates of contraceptive use (Marin, Gomez, Tschann, & Gregorich, 1997). Sexual comfort, or a general level of comfort and positive emotional orientation toward sexuality, has been found to foster sexual communication and contraceptive use self-efficacy, which in turn predicts greater contraceptive use (Marin et al., 1997). Sexual self-acceptance is an evaluation of one’s sexuality and has been positively associated with contraceptive use among ethnically diverse youth (Tschann & Adler, 1997). Another sexual value relevant to contraceptive use is gender role beliefs. Past studies with adult Latinos suggest that gender role beliefs—including expectations for women to be chaste, virtuous, and submissive to men and men to be strong, independent, and in a position of authority—influence expression of sexuality and sexual behavior (Marin, 2003).

Attitudes regarding sex, contraception, and pregnancy in adolescents and young adults can often be influenced by parental attitudes. Perceived parental attitudes toward sex and actual parental attitudes toward sexuality are strong predictors of adolescent and young adult sexual behavior (Bersamin, Todd, Fisher, Hill, Grube, & Walker, 2008). Overall quality of parental communication may function as a protective factor with effective communication styles and positive parental relationships being associated with fewer pregnancies and more consistent contraceptive use (Bersamin et al., 2008).

Method

The study examined ethnic differences in contraceptive use in a sample of female college students and investigates variables that may explain these differences including attitudes regarding sex, contraception, and pregnancy. Between 1995 and 2002, contraceptive use increased among European American youth but declined among Latino adolescents (Deardorff, Tschann, & Flores, 2008). Therefore, it was hypothesized (H1) that Latina participants would report lower rates of contraceptive use compared to non-Latinas. Important differences in sexual values may operate across cultural subgroups and contribute to ethnic differences in sexual activity (Deardorff, Tschann, & Flores, 2008). It was hypothesized (H2) that compared to non-Latinas, Latina participants would report different attitudes regarding sex, contraception, and pregnancy. It was predicted that Latinas would report lower levels of comfort with sexual communication and would have stronger beliefs that contraception was immoral. It was also hypothesized (H3) that attitudes regarding sex, pregnancy, and contraception would be significantly associated with contraceptive use. For example, lower levels of comfort with sexual communication and a stronger belief that contraception was immoral were hypothesized to predict lower rates of contraceptive use. Finally, it was hypothesized (H4) that ethnic differences in attitudes regarding sex, contraception, and pregnancy would indirectly influence and mediate the ethnic differences in contraceptive use. For example, it was hypothesized that Latina ethnicity would predict stronger beliefs that contraceptives were immoral, which in turn would predict lower rates of contraceptive use. Further, attitudes were hypothesized to mediate ethnic differences in contraceptive use, such that when ethnic differences in attitudes were statistically controlled, the effect of ethnicity on contraceptive use would be non-significant.

Participants

Participants included female students between the ages of 19-29 (M=22, SD=2.07) at the University of Texas at San Antonio. Participants were recruited through their psychology courses and volunteered to participate. Participants were excluded from analysis if they were over 30, if they were married, if they had children, or if they were virgins. Of the 72 females who completed the study, 7 percent (n = 5) were excluded from analysis, leaving 67 ethnically diverse female students who met the eligibility requirements. Of the 67 eligible participants, 43.3 percent identified as Latina, 34.3 percent as White, 9 percent as African American, 4.5 percent as Asian American, 1.4 percent as American Indian, and 7.5 percent as Other. For analysis, participants were categorized as Latina (43.3%) or non-Latina (56.7%).

Measures

Personal and demographic variables . Participants reported demographic variables including age, ethnicity, and religious affiliation. In addition to demographics, participants reported age at first sexual intercourse and number of lifetime sexual partners, their current relationship status, and how many children they had. The survey also included a shortened U.S. acculturation scale (how well do you know popular American TV and political leaders, I feel that I am part of American culture, I think of myself as being American, I speak English, my thinking is done in the English language; Zea, Anser-Self, Berman, & Buki, 2003). Participants responded on a four-point Likert scale with responses ranging from one to four, with higher scores signifying greater acculturation into the American culture (Cronbach’s α = .68 for respondents to our survey).

Attitudes toward sex. The comfort with sexual communication scale (Deardorff, Tschann, & Flores, 2008) includes eight items (see Table 1) that measure the level of comfort the respondent has when communicating about sexual topics. Items were measured using a four-point Likert scale with scores ranging from one (very uncomfortable) to four (very comfortable) with higher scores signifying greater comfort when talking about sex (Cronbach’s α = .86). The sexual self-acceptance scale (Deardorff, Tschann, & Flores, 2008), which we later refer to as sexual guilt, is composed of four items (see Table 1) that are used to assess the evaluation and acceptance of the respondent’s sexuality (Cronbach’s α = .77). Participants responded to each item using a five-point Likert scale with scores ranging from one (not at all) to five (very much), with higher scores signifying a higher level of sexual guilt.

Table 1

Sexual Attitude Scales and Items Included in the Survey

____________________________________________________________________________________Sexual Communication Comfort

- How would you feel talking about whether to use a condom?

- How would you feel talking about sexual positions?

- How would you feel talking about what feels good during sex?

- How would you feel talking about oral sex?

- How would you feel talking about what you would do about a pregnancy (like keep the baby, etc.)

- How would you feel talking about your sexual fantasies?

- How would you feel talking about what you don’t like during sex?

- How would you feel talking about the risk of STDs or HIV?

Sexual Guilt

- Do you think it is okay to have sex? R

- Do you think it is wrong to have sex?

- Do you feel guilty about having sexual feelings?

- Do you feel that having sex is embarrassing?

Traditional Gender Role Beliefs

- If the husband is the sole wage earner in the family, the financial decisions should be his R

- Both husband and wife should be equally responsible for the care of their children

- The first duty of a woman with young children is to home and family R

- A man who has chosen to stay home and be a house-husband is not less masculine than a man who is employed full time

- An employed woman can establish as warm and secure relationship with her children as a mother who is not employed

- A woman should not let child bearing and rearing stand in the way of a career if she wants it

Sexual Gender Role Beliefs

- It is expected that a woman be less sexually experienced than her partner

- A woman who is sexually active is less likely to be considered a desirable partner

- A woman should never appear to be prepared for a sexual encounter

- It is important that men be sexually experienced so as to teach the woman

- A “good” woman would never have a one night stand

- It is important for a man to have multiple sexual experiences in order to gain experience

- In sex, the man should take the dominant role and the woman should take the passive role

- One-night stands are expected of men

- It is worse for a woman to sleep around than for a man

- It is up to the man to initiate sex

- It is acceptable for a woman to carry condoms R

Parent-Child Sexual Communication

- Please indicate how much discussion you have had with your parents about the following topics

- a. Pregnancy

- b. Intercourse

- c. Menstruation

- d. Sexually Transmitted Disease

- e. Birth Control

- f. Abortion

- g. Prostitution

- h. Homosexuality

____________________________________________________________________________________

Note. R indicates that items are reverse coded

Participants completed the Liberal Feminist Attitude and Ideology Scale (Morgan, 1996) to assess traditional gender role beliefs (see Table 1 for items). Participants responded to six items on a five-point Likert scale with scores for each item ranging from one (strongly disagree) to five (strongly agree), with a higher score indicating less acceptance of traditional gender role beliefs (Cronbach’s α = .70). The Sexual Double Standard Scale also was administered (Caron, Davis, Halteman, & Stickle, 1993; see Table 1 for items). This scale includes eleven items assessing sexual gender role beliefs and was scored similar to the traditional gender role belief scale although a higher score on this scale indicated greater acceptance of traditional sexual gender roles (Cronbach’s α = .80). Parent-child sexual communication was measured using The Weighted Topics Measure of Family Sexual Communication (Fisher, 1998) (Cronbach’s α = .84; see Table 1). Participants were asked how much communication they had ever had with their parents about a variety of sexual topics. Participants responded on a one (none) to four (very much).

Attitudes toward pregnancy. Scales designed to identify participants’ attitudes toward pregnancy were included in the survey. Sixteen items (see Table 2) assessing perceived outcomes of pregnancy were used from The Juhasz-Schneider Sexual Decision Making Questionnaire (Juhasz & Kavanagh, 1987). Participants responded on a five-point Likert scale with scores for each item ranging from one (very improbable) to five (very probable), with higher scores signifying more negative perceived outcomes of a pregnancy (Cronbach’s α = .90).

Table 2

Pregnancy Attitudes Scale and Items Included in Survey ___________________________________________________________________________________Perceived Negative Outcomes of Pregnancy

- 1. If you got pregnant within the next year, to what extent would you experience the following outcomes?

- a. It would be embarrassing for your family

b. It would be embarrassing for you- c. You would have to quit school

d. You might marry the wrong person, just to get married- e. You would be forced to grow up too fast

f. You would have to decide whether or not to have the baby, and that would be stressful and difficult

g. Your sexual partner would have to decide (or help decide) whether or not to have the baby and that would be stressful and difficult

h. It would limit your independence

i. It would limit your social life

j. It would limit your education

k. It would limit your career

l. It would cause financial problems for you

m. It would limit your sexual partner’s independence

n. It would limit your sexual partner’s social life- o. It would limit your sexual partner’s education

p. It would cause financial problems for your sexual partner___________________________________________________________________________________

Personal approval of pregnancy was measured with the item “If you or a sexual partner were to become pregnant within the next year” with participants answering on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from one (it would be the best thing that could happen to me) to seven (it would be the worst thing that could happen to me). Family approval of pregnancy was measured with the item “If you or a sexual partner were to become pregnant within the next year, how would your family and those important to you feel?” Participants responded on a seven-point Likert scale with responses ranging from one (very much opposed) to seven (very much in favor).

Attitudes toward contraception. Items measuring perceived effectiveness and convenience of contraception were adapted from The Contraceptive Utilities, Intention, and Knowledge Scale (Condelli, 1984). Participants rated the extent to which they perceived eight forms of contraception as effective (Cronbach’s α = .70) and convenient (Cronbach’s α = .67) using a five-point Likert scale ranging from one to five with higher scores indicating positive perceptions (i.e., very effective, very convenient) and lower scores indicating negative perceptions (i.e., very ineffective, very inconvenient). The eight forms of contraception rated by participants included condoms, Depro-Provera, diaphragm or cervical cap, intrauterine device (IUD), Norplant, oral contraceptives, tubal ligation, and vasectomy of male partner.

General attitudes toward contraception were measured using 14 items (see Table 3) from the Contraceptive Attitude Scale (Black & Pollack, 1987). Participants responded using a five-point Likert scale ranging from one (strongly disagree) to five (strongly agree) with higher scores indicating more positive attitudes toward using contraception (Cronbach’s α = .81). Contraceptive immorality, or a feeling that using contraceptives is immoral was measured using four items (see Table 3) from A Scale to Assess University Women’s Attitudes About Contraceptive (Fisher, 1998). Items were scored on a five-point Likert scale with responses ranging from one (strongly disagree) to five (strongly agree) with higher scores indicating higher levels of immoral feelings toward using contraception (Cronbach’s α = .72).

Table 3

Contraceptive Attitude Scales and Items Included in Survey _____________________________________________________________________________________Contraceptive General Attitude Scale

- I believe that it is wrong to use contraceptives R

- I encourage my friends to use contraceptives

- I would not become sexually involved with a person who did not accept contraceptive responsibility

- Females who use contraceptives are promiscuous R

- I would not have intercourse if no contraceptive method was available

- Using contraceptives is a way of showing that you care about your partner

- I would feel more relaxed during intercourse if a contraceptive method was used

- Using contraception would enable me to regulate the size of my family

- It is no trouble to use contraceptives

- Sex is not fun if a contraceptive is used R

- Contraceptives encourage promiscuity R

- Couples should talk about contraception before having intercourse

- I would feel better about myself if I used contraceptives

- Contraceptives are worth using, even if the monetary cost is high

Contraceptive Immorality Scale

- Using contraception is immoral

- Using contraception would have a negative effect on my sexual morals

- Using contraception would give me guilty feelings

- Using contraception will produce children who are born with something wrong with them

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Note. R indicates that items are reverse coded

The extent to which social factors influence the respondent’s decision to use contraception was measured using five items from the The Juhasz-Schneider Sexual Decision-Making Questionnaire (Juhasz & Kavanagh, 1987). Each of the social factors was measured on a five-point Likert rating scale, with responses ranging from one (of no importance) to five (extremely important) in their decision in using contraception. Sample items included “My parent’s feelings about me using contraception”, “My friend’s feelings about me using contraception”, “My sexual partner’s feelings about me using contraception”.

Contraceptive Use . Contraceptive use was measured by providing participants with a list of 13 methods of contraception and asking them to indicate which forms of contraception they currently use and which forms of contraception they have ever used in the past. The list of contraception provided included condoms, Depro-Provera (“the shot”), diaphragm or cervical cap, IUD (Intrauterine device), Norplant (“the arm implant”), oral contraceptives (“the pill”), spermicidal foam or jelly, tubal ligation (“permanent surgical method for women”), vasectomy of male partner (“permanent surgical method for men”), withdrawal, emergency contraception (“the morning after pill, Plan B”), none, or other. Nearly half of the women in our sample reported ever using contraceptives and the method used by nearly all of these women was oral contraception (i.e., birth control pills). Because oral contraception was the most commonly used method among the women in our sample, contraceptive use in this study is specifically in regards to oral contraceptives.

Procedure

Institutional Review Board approval at the University of Texas at San Antonio was obtained prior to data collection. Data were collected through an anonymous self-administered survey, which took participants approximately 15 minutes to complete. Participants provided written informed consent and then were given class time in order to take the survey. It was left up to the professor of each particular course as to whether volunteers would receive extra credit for their participation, therefore, a small portion of the final participants received 15 extra credit points after completing the study whereas the other participants did not receive compensation for their participation.

Results

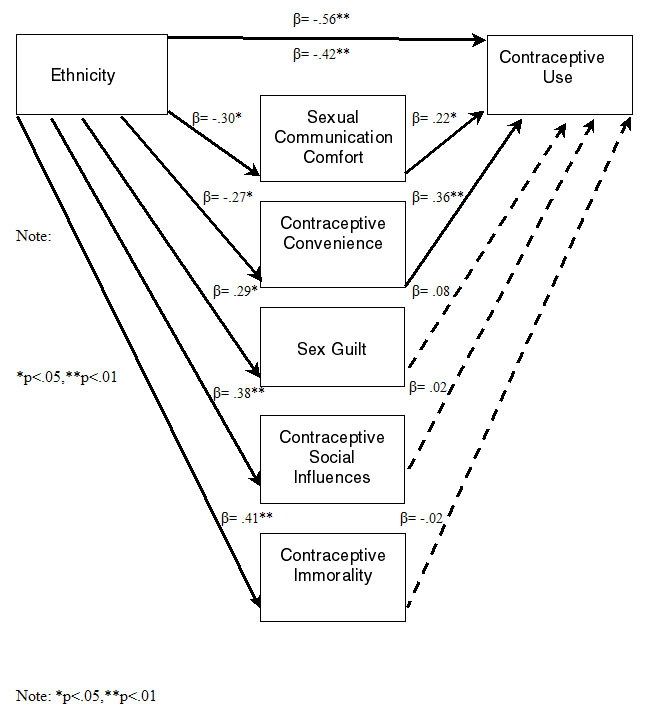

Regression path analyses were used to assess the direct and indirect effects of ethnicity on attitudes and contraceptive use (see Figure 1). In support of hypothesis #1 (H1), a significant direct effect of ethnicity was found on contraceptive use with Latina participants reporting lower levels of contraception F(2, 64) = 12.59, p<.001). In support of hypothesis #2 (H2), compared to non-Latinas, Latina participants reported significantly lower levels of comfort with sexual communication, F(2, 64) =5.55, p<.03, higher levels of sexual guilt, F(2, 64)=5.01, p<.03, more consideration of social factors on contraceptive use, F(2, 64)=5.54, p<.01, lower levels of perceived convenience of contraception, F(2,64)=4.16, p<.05, and a stronger belief that contraceptives are immoral, F(2,64)=5.40, p<.01. In support of hypothesis #3 (H3), lower levels of comfort with sexual communication and perceived contraceptive convenience were significantly associated with lower rates of contraceptive use,F(7,59)=7.00, p<.001. In partial support of hypothesis #4 (H4), when ethnicity and attitudes were entered into the same regression to predict contraceptive use, the direct effect of ethnicity on contraceptive use decreased slightly but was still significant, as depicted in Figure 1. Hence ethnic differences in contraceptive use were partially mediated by ethnic differences in sexual communication comfort and perceived contraceptive convenience (Baron & Kenny, 1986). Means and descriptive statistics for all variables can be found in Table 4, and correlations among significant variables can be found in Table 5.

Figure 1

Multiple Regression Path Analysis Results

Table 4

Means and Descriptives

_____________________________________________________________________________

Non-Latina Latinas Pregnancy Attitudes Personal Approval 2.76 (SD=1.50) 3.03 (SD=1.55) Family Approval 2.24 (SD=1.02) 2.62 (SD=1.01) Perceived Negative Outcomes 3.61 (SD=1.19) 3.03 (SD=1.22) Contraceptive Attitudes Contraceptive Convenience

4.18 (SD=1.01) 3.62(SD=1.47)* Contraceptive Effectiveness

4.40 (SD=.55) 4.25 (SD=.70) Contraceptive Social Influence

3.29 (SD=.89) 3.74 (SD=.65)* Contraceptive Use n= 26 (68%) n= 7 (24%)** Contraceptive Immorality 1.20 (SD=.30) 1.50 (SD=.48)** Sexual Attitudes Sexual Communication Comfort

3.57 (SD=.550) 3.19 (SD=.842)* Sexual Guilt

1.41 (SD=.588) 1.70 (SD=.705)* Traditional Gender Role Beliefs

4.20 (SD=.70) 4.10 (SD=.66) Traditional Sex Gender Role Beliefs

2.02 (SD=.67) 2.12 (SD=.72) Parent-Child Communication about Sex

2.49 (SD=.77) 2.53 (SD=.72) Other U.S. Acculturation 3.65 (SD=.31) 3.50 (SD=.42) Catholic Religious Affiliation

n= 7 (18%) n= 20 (69%)** Age at First Sex 17 (SD=1.84) 17 (SD=2.25) Number of Sexual Partners

6 (SD=5.48) 5 (SD=5.62) _____________________________________________________________________

Note: *p<.05, **p<.01

Table 5

Correlations Between Significant Variables

______________________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________________ 1. Sexual Communication 2. Sex Guilt 3. Contraceptive Social Influences 4. Contraceptive Immorality 5. Contraceptive Convenience ______________________________________________________________________________

Note: * p<.05Discussion

Corresponding with previous research and our study hypotheses, we found that Latina participants did report significantly lower rates of contraceptive use compared to the non-Latinas in our sample. In trying to determine the explanatory variables regarding ethnic differences in contraceptive use, only two of the proposed factors were found to play a significant role. These two factors were level of comfort with sexual communication and perceived convenience of contraception. These two variables were shown to provide an indirect path between ethnicity and contraceptive use, and may help to explain why Latina women report lower levels of contraceptive use compared to non-Latinas. Compared to non-Latinas, Latina women reported less comfort with sexual communication and perceived contraceptive convenience, which in turn predicted lower rates of contraceptive use. Although both level of comfort with sexual communication and perceived convenience of contraception were significantly associated with contraceptive use, they only partially mediated the relationship between ethnicity and contraceptive use.

Regarding assessment of contraceptive use in our sample, we found that nearly all of those women who did report ever using contraception reported using oral contraception. The Latina women in our sample however, reported much lower rates of oral contraceptive use compared to the non-Latinas. Previous research has demonstrated similar findings. According to Mosher, Martinez, Chandra, Abma, and Willson (2004), the leading method of contraception in the United States is the oral contraceptive pill. However, Latina women as well as African American women were less likely to have ever used the oral contraceptive pill, with the Latina women having the lowest rates of all groups. Previous research has also found that inconsistent use of oral contraception is more common among Hispanic women than among non-Latina white and other women (Peterson, Oakley, & Potter, 1998). Future research should examine contraceptive use as well as consistency of use.

Compared to non-Latinas, Latina women reported less perceived contraceptive convenience, which in turn predicted lower rates of contraceptive use. This low level of perceived convenience of contraception could indicate that Latina women find access to contraception difficult or that the actual use of contraception is inconvenient. Future research is needed to investigate why Latina women perceive contraception as less convenient than non-Latinas.

Latina women in this study reported lower levels of comfort with sexual communication compared to non-Latinas. Lower levels of comfort with sexual communication also predicted lower rates of contraceptive use. Women who feel less comfortable communicating about sexual topics may see greater barriers to obtaining contraception. Comfort with sexual communication has previously been associated with increased contraceptive use. Therefore, future research is needed to determine ways of increasing comfort with sexual communication among Latina women in order to increase pregnancy planning and decrease unintended pregnancy rates within this group.

Although this study found that attitudes provided significant indirect relationships between ethnicity and contraceptive use, attitudes did not fully mediate ethnic differences in contraceptive use. Hence, attitudes did not fully explain ethnic differences in contraceptive use. This suggests that future research is needed to investigate other explanatory variables. There are a number of factors that may influence the ethnic disparity in contraceptive use. For example, the poverty rate in the United States affects minority groups disproportionately. Low-income women have much higher rates of unintended pregnancy compared to women in other income levels. Financially disadvantaged women are more likely than other women to have unprotected intercourse. When they do use contraception, they experience markedly higher rates of method failure (Ranjit, Bankole, Darroch, & Singh, 2001). The disparity in the rate of contraceptive use in the United States among 18-24 year olds could also possibly be related to a lack of knowledge about contraception and to the lack of accessibility. According to Garces-Palacio, Altarac, and Scarinci (2008), knowledge about reproduction and contraception use was significantly lower among Hispanics than non-Hispanics. Furthermore, contraceptive use was significantly lower among Hispanics than among non-Hispanics.

Limitations

There were several limitations to the present study. The current study was completed using a relatively small sample. Increasing the sample size would likely produce more significant results. For instance, increasing the sample size may lead to an increase in the number of the explanatory variables that were found to be significant mediators of ethnicity on contraceptive use and therefore decrease the direct effect of ethnicity.

Despite their limitations, these findings provide information regarding individual beliefs and attitudes that can inform unintended pregnancy prevention programs. For example, encouraging Latina women to become comfortable talking about sexual topics may foster more consistent use of contraception. In addition, the disparities identified in this study suggest that policy efforts to reduce unintended pregnancy should focus on improving access to contraceptives, especially for high-risk groups of women. Also, policy makers should aim to help women plan pregnancies through the use of convenient and effective contraceptive methods.

References

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173-1182.

Bersamin, M., Todd, M., Fisher, D. A., Hill, D. L., Grube, J. W. & Walker, S. (2008). Parenting practices and adolescent sexual behavior: A longitudinal study. Journal of Marriage & Family, 70, 97-112.

Black, K. J. & Pollack, R. H. (1987, April). The development of a contraceptive attitude scale. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Southern Society for Philosophy and Psychology.

Condelli, L. (1984). A unified social psychological model of contraceptive behavior. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of California, Santa Cruz.

Caron. S. L., Davis, C. M., Halteman, W. A., & Stickle, M. (1993). Predictors of condom-related behaviors among first-year college students. Journal of Sex Research, 30, 252-259.

Chandra, A., Martinez, G. M., Mosher, W. D., Abma, J. C., & Jones, J. (2005). Fertility, family planning, and reproductive health of U.S. women: Data from the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 23(25).

Deardorff, J., Tschann, J. M.,& Flores, E. (2008). Sexual values among Latino youth: Measurement development using a culturally based approach. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 14, 138-146.

Finer, L. B. & Henshaw, S. K. (2006). Disparities of unintended pregnancy in the United States, 1994 and 2001. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 38, 90-96.

Fisher, T. D. (1998). Weighted Topics Measure of Family Sexual Communication. In C.M. Davis et al. (Ed.), Handbook of Sexuality-Related Measures (pp. 131-132). Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Garcés-Palacio, I. C., Altarac, M., & Scarinci, I. C. (2008). Contraceptive knowledge and use among low-income Hispanic immigrant women and non-Hispanic women. Contraception, 77, 270-275.

Juhasz, A. M., & Kavanagh, J. A. (1987). Factors which influence sexual decisions. Journal of Sex Education and Therapy, 4 , 35-35.

Marin, B. V. (2003). HIV prevention in the Hispanic community: Sex, culture, and empowerment. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 14, 186-192.

Marin, B. V., Gomez, C. A., Tschann, J. M., & Gregorich, S. E. (1997). Condom use in unmarried Latino men: A test of cultural constructs, Health Psychology, 16, 458- 467.

Mogran, B. L. (1996). Putting the feminism into feminism scales: Introduction of a liberal feminist attitude and ideology scale. Sex Roles, 34, 359-390.

Mosher, W. D., Martinez, G. M., Chandra, A., Abma, J. C., & Willson, S. J. (2004). Use of contraception and use of family planning services in the United States, 1982-2002. Advance Data From Vital and Health Statistics, 350. Hyattsville, Maryland: National Center for Health Statistics, 2004.

National Center for Health Statistics, Fertility, family planning, and reproductive health of U.S. women: data from the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth, Vital and Health Statistics, 2005, Series 23, No. 25

Peterson, L. S., Oakley, D., & Potter, L. S. (1998). Women’s efforts to prevent pregnancy: Consistency of oral contraceptive use. Family Planning Perspectives, 30, 19-23.

Ranjit, N., Bankole, A., Darroch, J. E., & Singh, S. (2001). Contraceptive failure in the first two years of use: Differences across socioeconomic subgroups. Family Planning Perspectives, 33, 19-27.

Santelli, J., Rochat, R., Hatfield-Timajchy, K., Gilbert, B. C., Curtis, K., Cabral, R., Hirsch, J. S., & Schieve, L. (2003). The measurement and meaning of unintended pregnancy. Perspectives on Sexual & Reproductive Health, 35, 94-101.

Tschann, J. M. & Adler, N. E. (1997). Sexual self-acceptance, communication with partner, and contraceptive use among adolescent females: A longitudinal study. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 7, 413-430.

Zea, M. C., Asner-Self, K. K., Berman, D., & Buki, L. P. (2003). The abbreviated multidimensional acculturation scale: Empirical validation with two Latino/Latina samples. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 9, 107-126.

|