Black and White Students’ Quality of Life

Dawnn Mahulawde

Bowling Green State University

Abstract

The Time-Oriented Quality of Life Scale (TOQLS) was developed to measure one’s present quality of life in relationship to one’s desired future quality of life. The ten items were economics, housing, family life, education, social life, neighborhood, transportation, desired career, mental health, and physical health. The population for this study consisted of 12 elementary, 14 middle school, 13 high school, and 15 college students. Results indicated that African Americans and Caucasians did not differ in reports of present or future quality of life but that elementary students had a lower future quality compared to the other age groups. The racial differences of quality of life are discussed.

Introduction

Quality of life is defined by Myers (2008) as one’s perceptions of his/her environment and health. There has not been extensive research conducted on racial differences in quality of life nor comparing quality of life developmentally. The Time-Oriented Quality of Life Scale (TOQLS) was used to assess those perceptions and racial differences that may exist among elementary, middle school, high school, and college students. It was hypothesized that black students would have a lower quality of life when compared to white students. It was also hypothesized that elementary students would perceive a higher future quality of life compared to college students.

Review of Literature

There has been much research on the assessment of quality of life. Quality of life has been synonymously used as life satisfaction. Researchers Pavot & Diener (1993) theorized that life satisfaction depends on a comparison of life circumstances to one’s standards. Various standards or indicators could measure these circumstances. Furthermore, Borthwick-Duffy (2000) stated that quality of life could relate to objective indicators and subjective indicators. Borthwick-Duffy defined objective indicators as life conditions and subjective indicators as life satisfaction.

Objective indicators and subjective indicators were assessed by Skarupski’s study using the Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQOL) scale. Purposefully, Skarupski (2007) assessed the racial differences of quality of life using older adults who were age 65 and over. Participants had age-related chronic conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease. In this quality of life study, black (N=3,707) and white (N=2,279) participants’ self-reported by using the HRQOL scale. Skarupski (2007) found that blacks had significantly lower HRQOL mean scores than whites. Furthermore, female HQROL scores increased with age and were higher than males. His finding was “attributable to the combined effects of social disadvantage, poor physical health, and lower cognitive function” (Skarupski, 2007, p. 293).

Research assessing middle schoolchildren quality of life between races was not significantly different. However, Huebner et al. (2006) did not assess quality of life or life satisfaction in relation to health but by other factors. The Andrew and Withey study (as cited in Huebner et. al., 2006) used the Brief-Multidimensional Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale (BMSLSS)to measure students’ life satisfaction in five areas (for example: family life, friendship, school experience, myself) on a 7-point scale. Huebner et al. (2006) used the BMSLSS on 1,290 white and 988 black six, seventh, and eighth grade students. It was concluded that there was no significant effect on BMSLSS scores of gender and race, although there was a significant effect on grade level; 6th graders reported higher BMSLSS scores than 8th grade students.

There are not many studies that address black and white differences in measuring quality of life; nonetheless, there is research conducted on black Americans’ quality of life. Gabbidon and Peterson (2006) created quality of life index and a living while black index using a comparative state analysis of African Americans living in 50 states. The authors used a comparative state analysis from numbers of prisoners, percentage of non-elderly who were uninsured, sales and receipts of African-American owned firms (in millions of dollars), poverty levels, infant morality rates, and homicide deaths. The authors’ dependent variables to measure quality of life included chronic drinking, mental health problems, suicide rates, and years of life lost before age 75. It was discovered that “the economic (poor earnings for African-American-owned businesses and poverty rate) and death stressors (infant mortality and death rates) were correlated with a negative quality of life for Black Americans” (Gabbidon & Peterson, 2006, p. 97). The authors surmised that the dependent variables to measure the quality of life might have contributed to the negative quality of life. The two independent variables, numbers of prisoners and percentage of non-elderly, did not correlate with quality of life for Black Americans (Gabbidon & Peterson, 2006).

Research conducted by Zullig et al. (2007) to evaluate the life satisfaction of college students used the BMSLSS to determine life satisfaction. The authors used college students (91 percent white) to conduct their study on life satisfaction in relationship to dieting behavior. The independent variables consisted of self-described weight, the degree of worry over weight, binge eating behavior, the degree of worry over binge eating behavior, duration of binge eating behavior, vomiting to get rid of food in the past year, and whether students described themselves as having an eating disorder. The dependent variable life satisfaction was condensed into three levels: dissatisfied, midrange, and satisfied. They concluded that “the majority of students reported at least midrange satisfaction of life or greater (76.2 percent of females and 73 percent of males), while approximately 24 percent of females and 27 percent of males reported being dissatisfied with life” (Zullig et. al., 2007, p. 23).

Browne (2006) conducted a longitudinal study that examined life satisfaction in relationship to the Big Five dimensions of personality and career decision status of black college students (2006). Participants included three hundred and thirty-three undergraduates. The Career Decision Scale (CDS), the NEO Personality Inventory - Revised (NEO PI-R), and a single item drawn from the Index of Well Being were used to measure career decision status, personality traits, and life satisfaction, respectively. There was a positive relationship between life satisfaction and career decision status; life satisfaction predicted career decision status. Nevertheless, there was not a significant relationship between career decision status and personality (Browne, 2006).The previous research only dealt with one’s present quality of life or life satisfaction. It also did not compare different age groups (elementary, middle school, high school, and college). The Time-Oriented Quality of Life Scale (TOQLS; Pomales, 2008) was designed to measure a person’s present quality of life in relationship to one’s desired future quality of life. Quality of life was calculated by totaling one’s present quality of life and one’s future quality of life.

Assessing students’ quality of life is important to determine the distance one is from his or her goals in life. As students attending school, there should be quite a distance between student’s desired goals and current progress. Specifically, the greater the distance students are from their goals the less satisfied, the less the distance the more satisfied.

In the TOQLS, quality of life contains the following ten variables: economics, housing, family life, education, social life, neighborhood, transportation, desired career, mental health, and physical health. These are all aspects of life that makes one content. Particularly, quality of life is how well one is managing presently in life in relationship to how well one desires to manage in the future.

The present study examined the black and white students and the present and future quality of life using the TOQLS (Pomales, 2008). It was hypothesized that elementary, middle school, and high school students would have higher mean scores for their future quality of life than college students. Piaget’s Concrete Operational Stage indicated that children from ages 7 to 11 would not be able to think abstractly about the future. Piaget’s Formal Operational Stage indicated that adolescents from age 11 to 16 would be able to think abstractly beyond the present. It was also hypothesized that black students would have a lower quality of life compared to white students. Research by Skarupski (2007) determined the blacks had a lower quality of life due to social disadvantages (poverty).

Methodology

Participants were selected from previous or current schools attended by the researcher. Elementary and high school students were selected from 4 midwestern small middle-class schools. Participants were 12 elementary students, 14 middle school, and 13 high school students. Fifteen college students were selected from Bowling Green State University. All students were asked to participate in the study. A demographic questionnaire was given to assess each student’s background. Items on the demographic questionnaire consisted of age, race, two-parent vs. one parent home, and future aspirations. Four questionnaires were incomplete and were not used in the study. The TOQLS assessed present and future quality of life. Present quality of life and future quality of life were totaled for all ten items for each group. The midpoint was 40, which indicated that the student had an average present or future quality of life. However, the mean and standard deviations were to be determined because this instrument was new.

Results

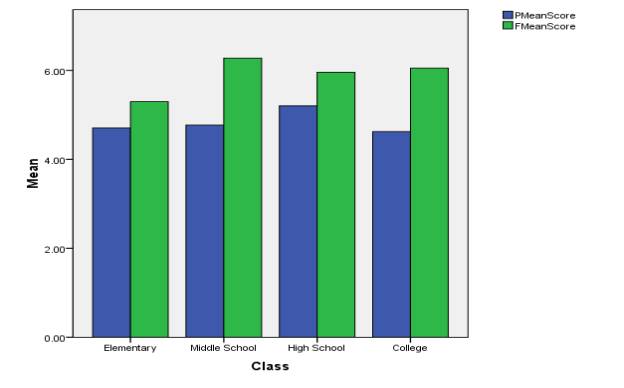

A one-way ANOVA calculated age differences in future quality of life (see figure 1). Elementary students scored a mean of 5.30 with a standard deviation of 0.81, middle school students scored a mean of 6.27 with a standard deviation of .37, high school students scored a mean of 5.96 with a standard deviation of .76, and college students scored a mean 6.05 with a standard deviation .60 [f (3.50)= 5.32, p < .05]. Post Hoc Scheffe was conducted on age differences in future quality of life. It showed a significant mean difference amongst elementary and middle school students, p = .05. It also showed a significant mean difference between elementary and college students, p= .39. There was not a significant mean difference between elementary and high school students, p > .05. An independent samples t-test was used to test the hypothesis that black students had a lower present quality of life compared to white students. African Americans on average scored 4.66 and Caucasians on average scored 4.98 [t (52) = 2.1], p = 0.16].

Figure 1. Present and future quality of life mean scores of students.

Discussion

Elementary, middle school, and high school students were expected to have higher mean scores compared to college students for their future quality of life. It was expected that students would not be able to make decisions regarding their future due to the fact that it was a non-tangible concept. This finding was contradictory to previous research using the Brief-Multidimensional Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale, which found significance in middle school students reporting life satisfaction. Also, Piaget’s concrete operational stage was not supported. Children could think abstractly beyond the present. Specifically, elementary and middle school students were able to think abstractly about the ten variables. This could suggest that younger children should not be underestimated in the thought process. Racial differences with quality of life did not exist, which could be due to the fact that race is not biological. This could help end common stereotypes. One stereotype that could be questioned is that blacks are inferior to whites. Although there were no racial differences between all students regarding present quality of life, a larger sample size was needed. There could be some racial differences in quality of life due to one’s socio-economic status and other demographic variables. In future studies, one could focus more on socio-economic questions such as mother and father’s income, whether or not the child works outside of school, and others to determine whether a correlation with quality of life exists.

References

Borthwick-Duffy, S. A. (1992) Quality of life and quality of care in mental retardation. In L. Rowitz (ed). Mental Retardation in the Year 2000. Berlin: Springer-Verlag (pp. 52-66).

Browne, J. M. (2005). Personality, life satisfaction, and career decision status: An examination of factors that impact the career decisions of Black college students. Ph.D. dissertation, Howard University. Retrieved November 3, 2008, from Dissertations & Theses: A&I database. (Publication No. AAT 3184854).

Gabbidon, S. L., & Peterson, A. (2006). Living while Black: A State-Level Analysis of the Influence of Select Social Stressors on the Quality of Life Among Black Americans. Journal of Black Studies, 37(1), 83-102.

Huebner, E. S., Suldo, S. M., Valois, R. F., & Drane, J. W. (2006). The Brief Multidimensional Students' Life Satisfaction Scale: Sex, race, and grade effects for applications with Middle school students. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 1 (2), 211-216.

Myers, D. (2008). Social Psychology. New York, New York: McGraw Hill.

Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (1993). Review of the Satisfaction With Life Scale. Psychological Assessment, 5(2), 164-172.

Pomales, M. (2008). Time-Oriented Quality of Life Scale. Bowling Green, OH: BowlingGreen State University, Center for Multicultural and Academic Initiatives.

Skarupski, K. A., de Leon, C. F. M., Bienias, J. L., Scherr, P. A., Zack, M. M., Moriarty, D. G. et al. (2007). Black-white differences in health-related quality of life among older adults. Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care & Rehabilitation, 16(2), 287-296.

Zullig, K. J., Pun, S. M., & Huebner, E. S. (2007). Life satisfaction, dieting behavior, and weight perceptions among college students. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 2(1), 17-31.

This research was conducted with assistance from Takarra Dunning, Masters of Social Work, Western Michigan University.

503-510.

|