The Effect of Task Types on EFL Learners' Listening Ability

Masoud Bahrami

Islamic Azad University, Iran

Abstract

This study aimed at examining the influence of task-based activities (four specific types of tasks: matching, form-filling, labeling, and selecting) on listening ability in students of English as a foreign language and to identify if there was any correspondence between task type and students' language proficiency level. Ninety senior EFL learners of Sadra English Institute in Dorood participated in this study. The sources of data for this quasi-experimental study included two task-based tests of listening comprehension and a test of language proficiency. Analysis of the findings indicated that there was a significant relationship between the three tasks of "matching, labeling, and form-filling" on the one hand and listening comprehension on the other. However, no such relationship was observed between the task of "selecting" and listening comprehension. Moreover, the results of the participants' performance on each task at each level of language proficiency showed that among the four tasks of the study only the "selecting" task did not correspond with the three levels of language proficiency. The participants, according to the results of the post-test, showed no improvement over the task of "selecting".

Key words: Listening comprehension, task types, EFL learners.

Introduction

General background

Listening comprehension traditionally has drawn the least attention of the four skills (reading, writing, listening, and speaking) in terms of both the amount of research conducted on the topic and its place in language teaching methodology (Morley, 1990; Rivers, 1981). This neglect may have stemmed from the fact that listening is considered a passive skill, and from the belief that merely exposing the student to the spoken language is sufficient for listening comprehension. During the time when audiolingualism was the prevailing approach in foreign language teaching, it was assumed that students' listening skill would be enhanced automatically as a result of their repetition of dialogues and pattern drills. Accordingly, developing the listening skill per se was allocated very little attention in foreign language classrooms, and most structured listening practice took place in the language laboratory (Herron & Seay, 1991). This approach more or less has also been prevalent in Iran. In fact, little effort has been expended on the part of English teachers to enhance students' listening comprehension ability per se.

Obviously, the most pervasive changes to language teaching practice over the last twenty years are those that can be described as communicative language teaching (CLT). Chastain (1988, p. 163) believed that by the emergence of Communicative Language Teaching (CLT) in the history of language teaching and learning, the goal of language teaching and learning shifted to achieving communicative competence. As far as CLT is concerned, one can claim that it paid attention to all the four skills of language—reading, listening, speaking, and writing. Listening was no longer believed to be a passive skill. CLT and its subsequent branches considered listening as an active skill. One of CLT’s subsequent divisions has been Task-Based Language Teaching (TBLT), which is based on using tasks as the core of language teaching and learning.

Tasks for Listening Comprehension

As a general rule, exercises for listening comprehension are more effective if they are constructed around a task. The students should be "required to do something in response to what they hear that will demonstrate their understanding" (Dunkel, 1986, p. 104; Ur, 1984, p. 25). Examples of tasks are answering questions appropriate to the learners' comprehension ability, taking notes, taking dictation, and expressing agreement or disagreement. However, Dunkel (1986) and Wing (1986) suggested that listening activities should require the students to demonstrate listening skills. Consequently, listening exercises should be dependent upon students' skills in listening, rather than skills in reading, writing, or speaking.

There are different types of tasks that the students can perform without speaking, reading, or writing. One is a transferring exercise that involves "receiving information in one form and transferring the information or parts of it into another form" (Richards, 1983, p. 235), such as drawing a picture or a diagram corresponding to the information given (Dirven & Oakeshott-Taylor, 1985; Dunkel, 1986; Lund, 1990; Paulston & Bruder, 1976; Richards, 1983; Ur, 1984). Another kind of listening task is a matching exercise that involves selecting a response from alternatives, such as pictures and objects, that correspond with what was heard (Lund, 1990; Richards, 1983). Samples of this type of exercise are choosing a picture to match a situation and placing pictures in a sequence, which matches a story or set of events (Richards, 1983). The other type of listening task involves physical movement (Dunkel, 1986; Lund, 1990; Ur, 1984); that is, the students have to respond physically to oral directions.

Few empirical studies, however, have explored the potential relationship between task-based approach and language skills, specifically the listening comprehension.

Task-based language teaching

Task has been defined in a variety of ways. Nunan (1999), for example, defined a task as

A piece of classroom work that involves learners in comprehending, manipulating, producing or interacting in the target language while their attention is focused on mobilizing their grammatical knowledge in order to express meaning, and in which the intention is to convey meaning rather than to manipulate form. The task should also have a sense of completeness, being able to stand alone as a communicative act in its own right with a beginning, a middle and an end. (p. 25)

Littlewood (2004) made a distinction between a task and an exercise. It is said that a task is meaning-focused whereas an exercise is form-focused. Although a task has got a non-linguistic outcome, an exercise has a linguistic outcome, and finally a task is connected with the pragmatic meaning but an exercise deals with the semantic meaning.

Doughty and Pica (1986) reported the findings of the latest series of studies to determine the effects of task type and participation pattern on language classroom interaction. The results of this study were compared to those of an earlier investigation in regard to optional and required information exchange tasks across teacher-directed, small-group, and dyad interactional patterns. The participants in both the earlier and the present studies were adult students and teachers from six intermediate EFL classes (three classes in each of the two studies). The classes were selected according to the proficiency level. The students who participated in group- and dyadic-activities were chosen randomly with a variety of L1 backgrounds. The teachers were native speakers of English with several years of teaching experience. The findings showed that group and dyad interaction patterns produced more modification than did the teacher-fronted situation, which suggested that the participation pattern as well as the task type have an effect on the conversational modification of interaction.

Jean and Hahn (2006) explored teachers' perceptions of task-based language teaching (TBLT) in a Korean secondary school context. The participants were 228 teachers (153 females, 75 males) at 38 different middle and high schools in Korea. A three-page questionnaire (including demographic questions, questions about the basic concept of task and principle of task-based instructions, and questions related to teachers' position on classroom practice of TBLT) was used to measure Korean EFL teachers' perception of TBLT in a classroom setting. The overall findings of the survey showed that the majority of respondents had a higher level of understanding about TBLT concepts, regardless of teaching levels, but there existed some negative views on implementing TBLT with regard to its classroom practice.

In conclusion, it can be claimed that listening in an L2 has received relatively little attention by researchers despite its obvious importance both as a skill in its own right and as one of the primary sources of language acquisition. In addition to the research reported above, there is some supporting evidence that a meaning-centred approach is effective in developing proficiency (for example, Lightbown, 1992), and there is also growing experimental evidence that the attention to form that arises from the negotiation of meaning in task-based activity promotes acquisition (for example, Mackey, 1999). Despite the Ellis (2003, p. 209) claim that no empirical study has ever investigated the effect of task-based methodologies on EFL learners' listening abilities, this study has demonstrated that tasks can serve as an effective methodological tool for investigating both theoretical and pedagogically relevant aspects of listening.

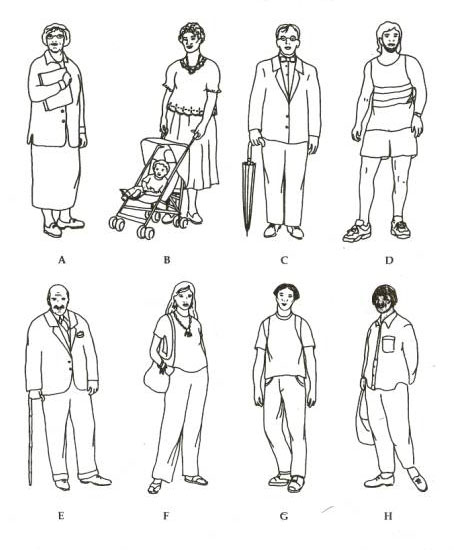

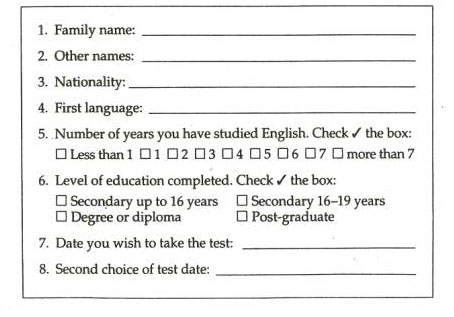

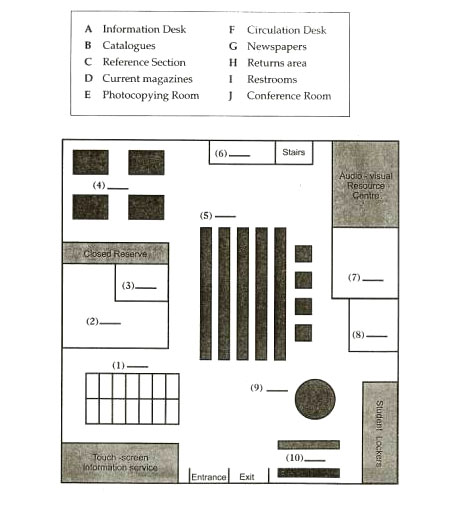

The purpose of this study was to test the practical usefulness of task-based approach in teaching listening. The study sought to determine whether teaching listening through task-based approach could be influential in EFL listening improvement. Because the previous studies in this regard had hardly dealt with applying the tasks designed by the researcher, this study afforded exclusivity to the literature in the sense that it encompassed the four specific task types specified: labeling, selecting, matching, and form-filling. For the labeling task, the participants were asked to label buildings on a map. For the selecting task, the participants were asked to choose a film from three trailers. For the matching task, the participants were asked to match descriptions to the pictures; and finally for the form-filling task, they were asked to fill out a hotel registration form.

As far as teaching listening is concerned, the findings of this study will help foreign language teachers to choose the appropriate way of teaching listening to EFL learners. This study, following the previous ones, focused on the effects of the task-based activities on improving EFL learners' listening ability. Because the questions raised in this study have not been dealt with in the previous literature, it makes this study an important scholarly investigation. Therefore, it was intended to give the researcher enough confidence that the study is well worth the effort as it, in turn, will enhance the existing theories on task-based methodologies. The present study was concerned with the investigation of the effect of four specific types of tasks on Iranian EFL learners' listening ability. Furthermore, the investigation of the probable correspondence between the tasks and students' language proficiency level added to the novelty of the study.

This study attempted to answer the following questions:

- Is there any significant relationship between task type and Iranian EFL learners' listening ability?

- What type(s) of task correspond to the students' language proficiency level?

Methodology

Setting and participants

The participants of this study were chosen from among the senior EFL learners of Sadra English Institute in Dorood. Ninety students were chosen randomly. They had studied English at language institute for ten semesters or so, and could easily follow the listening procedure designed by the researcher. Then they were put into three levels of intermediate, upper-intermediate, and advanced based on their scores in an Examination for the Certificate of Proficiency in English (ECPE) test. They were all female and their ages ranged from 19 to 26. Based on the results of the pre-test (language proficiency test) of the study, the researcher noticed that their listening comprehension suffered. By promoting the importance of listening and its role in foreign language learning, the participants were gradually motivated, and an attempt was made to keep them motivated during the course via the presentation of interesting and authentic topics.

Instrumentation

Pre-test.

The pretest in this study consisted of two parts: a test of language proficiency and a task-based test of listening comprehension (both made reliable through KR-21 formula). The two tests showed a reliability coefficient of 0.79 and 0.83 respectively. The language proficiency test was a simulated ECPE proficiency test (Briggs, Dobson, Rohlck, Spaan & Storm, 2001), which in its entirety was run in order to enable the researcher to judge the learners' language proficiency level. Because of their subjectivity, the speaking and writing sections were removed. Time limitation was another reason for the researcher to delete half of the whole items of other sections (25 items from 50 items of listening; 35 items from 70 items of grammar and vocabulary; and 15 items from 30 items of reading). In order to have randomly selected items, the researcher selected only the odd items of the test. Being put into three levels of language proficiency (intermediate, upper-intermediate, and advanced), the participants took the task-based test of listening comprehension (Cameron, 2000), and their scores were compared with the results of the post-test. This test helped the researcher track the learners' listening improvement. The test had four sections, each devoted to one of the four tasks consisting of 8 items. So, the whole test consisted of 32 items. Thirty-two minutes were allowed plus 5 minutes to check answers and to transfer them to the answer sheet. The participants were instructed to listen to the four separate sections and answer the questions as they were listening. The tape was played only once.Post-test.

The post-test in this study was another sample task-based test of listening comprehension (Cameron, 2000) to determine the efficacy of the task types on the listening comprehension of EFL learners and to see whether there were any significant relationships between the tasks and students' language proficiency level. The post-test had the same characteristics of the task-based pre-test of listening comprehension.Procedure

The study was conducted at the start of the term (each educational year in Sadra English Institute is divided into four terms). In order to determine the participants' level of language proficiency, an ECPE test was administered. Students whose scores fell + 0.5 standard deviation (SD) or more above the mean were considered advanced learners. Those students whose scores fell between + 0.5 SD above and - 0.5 SD below the mean were considered as upper-intermediate. And finally those whose scores fell from - 0.5 to -1 SD below the mean were chosen to represent intermediate group. This way, there were three groups of intermediate, upper-intermediate, and advanced. After putting them into three groups, they were given special listening tasks for the whole term that took twenty sessions (10 weeks, two sessions a week). In fact, special listening tasks were designed for each group to be practiced through the task-based approach. The four tasks were labeling, selecting, matching, and form filling, which were applied according to the framework introduced in Richards and Renandya (2002, p. 244). The four tasks were practiced by each of the three groups of participants. Because the four tasks specified in this study were purely receptive ones and there was no demand on the subjects' part for language production, the validity of the tasks was protected.

The rationales for choosing a task-based syllabus and adopting its principles as the means of conducting this study are summarized as follows

- According to Prabhu (1987), the engagement of learners has been emphasized in these syllabuses. Tasks establish a reasonable challenge and are cognitively motivating so that their accomplishment will provide learners with a sense of achievement.

- According to Ellis (2003, p. 209), tasks serve as a suitable unit for specifying learners' needs and thus for designing specific purpose courses.

Among the various listening tasks, the researcher selected these four specific types because they were purely receptive ones in contrast with others (e.g., note-taking), and there was no demand for language production on the part of the learners. This way, the researcher tapped the participants' listening ability both before and after the instruction.

Concerning the selection of listening materials that would fit each level of proficiency appropriately, Scrivener (1994, p. 150) argued that it is not the material (the recording) that should set the level of the lesson: it is the task. In practice, however, he acknowledged that some tapes, of course, are naturally going to seem more appropriate for specific levels of students. Thus a tape of someone asking for directions in the street is more likely to be usable at a lower level than, say, a discussion on complex moral issues. In this study the four types of tasks were practiced by each of the three groups, and they only differed regarding the topic and language system (grammar and vocabulary). The difficulty level of the taped texts was determined via Fog readability formula (Farhady, Jafarpur, & Birjandi, 2000, p. 282). Cameron (2000) also claimed that these types of tasks are quite suitable for all levels of language proficiency.

Concerning the lesson plan or the sequence of class activities, the following route-map was made and implemented throughout the course: a) lead-in, b) pre-task-work, c) the actual task, d) tape playing, and e) feedback on the task.

Lead-in: involved pre-listening activities, introduction to topic, discussion, looking at pictures.

Pre-task work: included looking through worksheet, work on vocabulary, prediction

The actual task: involved performing each of the four actual task types of the study, e.g. filling out a hotel registration form.

Tape playing: the teacher first played the tape and then asked the students to perform the task individually. If they could not achieve the point individually, the teacher would play the tape a number of times so that the students could discover the correct words and compare their findings in pairs or in groups after each time of playing. The repeated this strategy until students could discover the exact words and could obtain the teacher's approval. Eventually, if they could not find it, the teacher provided the exact word.

Prabhu (1987) stated that learners must be encouraged to complete the task on their own, so they should be provided with such a chance. This resulted in “sustained self-dependent effort by learners” and could help to foster independence and autonomy (p. 58). Nunan (1989) believed that working on one's own could be intrinsically motivating.

However, working collaboratively on tasks would enable learners to perform beyond the capacities of any individual learner. Dewey (1916, p. 302), many years ago, held that "certain capacities of an individual are not brought out except under the stimulus of associating with others." Jacobs (1998) provided a comprehensive list of ten potential advantages of group/pair work for language pedagogy. Among these were increase in motivation, independence, enjoyment, and social integration.

With regard to the above-mentioned claims, the researcher chose to take an eclectic approach, including both individual and collaborative learning endeavors on the part of the learners. Feedback on the task depended on the learners' performance (whether they had done the task successfully or not).

As far as task sequencing was concerned, the tasks and materials were graded so as to facilitate maximum learning. In effect, this required determining the complexity of individual task types so that tasks would match to learners' level of development. Widdowson (1990, p. 85) noted that sequencing tasks faces several problems, in particular the grading criteria to be used. He pointed out that we do not possess a sufficiently well defined model of cognitive complexity to establish such criteria and concluded that task-based syllabuses face exactly the same problem as linguistic syllabuses; they cannot be modeled on the sequence of language acquisition. Ellis (2003, p. 220) mentioned that tasks do not need to be graded with the same level of precision as linguistic content. He believed that the ease with which learners are able to perform different tasks depends on three sets of factors: a) the inherent characteristics of the task itself (task complexity), which deals with the nature of input, the task conditions, the processing operations involved in completing the task and the outcome that is required; b) factors relating to learners as individuals, which include learner's level of proficiency, intelligence, language aptitude, learning style, memory capacity and motivation; and c) the methodological procedures used to teach a task, which can in turn increase or ease the processing burden placed on the learner and are related to the use of pre-task activity (e.g., pre-teaching the vocabulary needed to perform the task) or carrying out a task similar to the main task with the assistance of the teacher, and planning time (i.e., giving students the opportunity to plan before they undertake the task).

Among the above-mentioned factors the researcher chose the most concrete and measurable criteria for grading the tasks. It is also necessary to mention that since the four tasks of this study (listening tasks) belonged to the same class, they had most features in common. As far as the first criterion (task complexity) was concerned, all the variables were shared by the tasks except their input features. With regard to input, the tasks were distinguished based on a) input medium (according to Prabhu (1987, p. 86) tasks involving pictures and diagrams frequently figure in courses designed for learners of limited proficiency.); and 2) context dependency (textual input that is supported by visual information in some form is generally easier to process than information with no such support). Nunan (1989, p. 96) also noted that texts supported by photographs, drawings, tables, and graphs were easier to understand. With regard to other variables of the first factor, no difference was found among the four tasks. For example, when it came close to the “output” section, based on the Prabhu's criteria, all tasks of this study were the same since they consisted of instructions that did not require learners' production. In other words, they all functioned as comprehension rather than production tasks. So, the researcher accordingly ordered the tasks in such a way that the “labeling and matching” preceded the “form-filling and selecting,” because the first two were pictorial or diagram-based. The results of the participants' performance on each task in the pretest (task-based pretest) were also used by the researcher. Thus, the tasks were presented in the following order: a) matching, b) labeling, c) form-filling, and d) selecting.

Concerning the second criterion variables (i.e., those relating to the learners as individuals), only their level of proficiency was controlled by the researcher. And finally, as far as the third criterion was concerned, the same methodological procedures were applied by the researcher for the implementation of the four tasks.

The tasks were ordered only on the basis of their complexity, and other factors were taken as neutral (i.e., they were not assigned any role concerning the task sequencing).Of the 23 sessions, 3 sessions were used for administration of the tests, the first two sessions for the two pre-tests (test of language proficiency and task-based test of listening comprehension), and the last one for the post-test (task-based test of listening comprehension). Each session lasted about 90 minutes, and the time was equally divided among the four tasks.

Some general guidelines and strategies were recommended to the students at the beginning of each session. The students were also reminded of these strategies when it was felt necessary before and even after each activity. The strategies devised and adapted primarily from Cameron (2000) were of two types: pre-listening strategies and while-listening strategies:

- Pre-listening strategies

- - Read the question.

- - Check whether you have to write your answer, and in what form (a name, a number, a tick or a cross, a phrase, circle the correct answer,…).

- - Predict the content of what you will hear.

- - Anticipate the words and phrases you are most likely to hear.

- - Translate any pictures into words to anticipate hearing them in the listening passage.

- - Predict possible answers to the questions to prepare yourself to hear the answers.

- - Anticipate synonyms and ideas expressed in different words.

- - Concentrate!

- While-listening strategies

- - Listen carefully to any taped instructions for each section.

- - Focus on more than one question at a time.

- - Do not stop on an answer you do not know: move on.

- - Listen for the specific information pin-pointed in your pre-listening preparation.

- - Do not worry if you do not understand every word when listening for the overall meaning or gist.

- - Write an answer for every question: sometimes your guesses are accurate because your ears hear more than you think.

- - At the end of each section check your answers and transfer them with care to the answer sheet.

Based on these general guidelines, the researcher devised specific strategies for the four tasks specified in his study that are in line with those prescribed by most popular syllabus designers like Cameron (2000). These strategies were highly concentrated, and the participants were repeatedly invited to take them into account. As highly recommended for task accomplishment, the strategies potentially encouraged the learners to keep themselves aware of their importance. The strategies for each task type are listed below:

- Labeling a diagram:

- - Examine the diagram closely in the time given.

- - Predict what the parts / sections / places might be called.

- - Anticipate how locations / features might be described.

- - Listen carefully to instructions.

- Form-filling:

- - Read the form carefully and think of how the words will sound when you hear them.

- - Although you must try to predict, do not cling too tightly to your predictions.

- Matching:

- - Look carefully at the graphics in the time given.

- - Think about what you know about the object in the diagram.

- - Anticipate the vocabulary and ideas you might hear.

- - Identify the differences between the pictures.

- Selecting:

- - Read the questions in the time given.

- - Anticipate the vocabulary and ideas you might hear.

- - Predict what to listen for to decide the answer.

- - Do not eliminate any answers until you have heard the text, no matter how unlikely they may seem.

Scoring procedure

The right/wrong scoring procedure was used in this study. A response received a score of '0' if it was wrong and '1' if it was correct.

Data analysis

Once the data related to the three groups of the study were gathered, they were subjected to the statistical analysis of ANOVA and t-test in order to see if the observed differences were significant. Concerning the first question of the study, the researcher applied four paired t-tests to see if there was any significant relationship between each of the four tasks and the listening comprehension of the participants, disregarding their level of language proficiency. As far as the second question of the study is concerned, the researcher conducted twelve paired t-tests (three for each of the tasks) to determine if there was any significant relationship between the task in question and the participants' level of language proficiency.

Findings

In order to find out whether the whole treatment (task-based activities) affected the participants' performance (listening comprehension) in the three levels of language proficiency, the researcher conducted a two-way ANOVA (Table 1).

Table 1. Two-way ANOVA on the participants' performance in the three levels of language proficiency

Source

SS

df

MS

F

Between group

0.780

1

0.780

6.554

Within group

3.461

29

0.119

P<0.05

The F-observed value (6.554) exceeded the value of F-critical (4.18) at 0.05 level of significance, which indicated that the difference between the two means was statistically significant. This difference between the two F-values is high enough to make the researcher confident in attributing the difference to the treatment effect.

The results of the participants' performance on pretest and post-test tasks

Concerning the first question of the study, the researcher applied four paired t-tests to determine if there was any significant relationship between each of the four tasks and the listening comprehension of the participants, disregarding their level of language proficiency.

As mentioned before, the two tests (pretest and post-test), each containing 32 items (8 items four each task) of listening comprehension, were administered to the students. The information was subjected to statistical analysis, descriptive and inferential. To find out whether the differences between the subjects' means on each individual task were statistically significant or not, matched (paired) t-tests were conducted. What follows is a presentation of the results obtained from the analysis of the participants' performances (90 students) on the four tasks (Table 2).

Table 2. Matched t-test of the participants' performance on the four tasks

Task

Mean of pretest

Mean of post-test

SD of pretest

SD of post-test

t-observed

Matching

4.1667

4.4333

1.47831

1.54374

5.391

Form-filling

4.2111

4.4444

1.48774

1.42301

4.658

Labeling

4.2556

4.5556

1.47306

1.41510

6.176

Selecting

4.2333

4.2889

1.68303

1.63696

1.043

P-value≤0.05 n = 90 df = 89 t-critical = 2.000

The t-observed values for the tasks of "matching, form-filling, and labeling" (5.391, 4.658, 6.176) exceeded the value of t-critical at the 0.05 levels, and only the t-observed value for the "selecting" task (1.043) is lower than the critical t-value (2.000). The above statistical procedures answered the first question of the study: from the four tasks designed for teaching listening comprehension, only the effect of the selecting task was low and the three others improved the participants' listening comprehension as a result of task-based methodology.

The results of the participants' performance on the tasks in each level of language proficiency

The researcher conducted twelve matched (paired) t-tests for each of the tasks in the three groups of language proficiency to determine if there was any correspondence between the task in question and the participants' level of language proficiency. What follows is the presentation of the results obtained from the analysis of the participants' performance on each task in the three levels of language proficiency. As mentioned before, there were 30 students in each of these levels.

Table 3. Matched t-test of the participants' performance on the tasks in each level of language proficiency

Task / level of proficiency

Mean of pretest

Mean of post-test

SD of pretest

SD of post-test

t-observed

Matching/intermediate

3.6667

3.9333

1.44637

1.55216

3.247

Matching/upper-intermediate

4.1000

4.3667

1.47040

1.40156

3.247

Matching/advanced

4.7333

5.0000

1.36289

1.53128

2.804

Form-filling/intermediate

3.6667

3.9667

1.49328

1.42595

3.525

Form-filling/upper-intermediate

4.1667

4.4000

1.28877

1.30252

2.536

Form-filling/advanced

4.8000

4.9667

1.49482

1.40156

1.980

Labeling/intermediate

3.8000

4.0333

1.49482

1.37674

2.971

Labeling/upper-intermediate

4.3333

4.6667

1.60459

1.47001

3.808

Labeling/advanced

4.6333

4.9667

1.21721

1.27261

3.808

Selecting/intermediate

3.9333

3.8333

1.61743

1.62063

1.140

Selecting/upper-intermediate

4.1667

4.3667

1.60459

1.47001

1.989

Selecting/advanced

4.6000

4.6667

1.58875

1.64701

0.812

P-value≤0.05 n = 30 df = 29 t-critical = 2.045

As it was revealed statistically and also as far as students' language proficiency level is concerned, the study demonstrated that, at the intermediate level, all the tasks showed some degrees of correspondence with the level in question except the task of "selecting.” In the upper-intermediate level, all the tasks corresponded with this level except the "selecting" task. And finally, in the advanced level, the two tasks of "matching" and "labeling" showed correspondence to the level in question, and the two others did not.

Discussion

The relationship between tasks and listening comprehension

As far as the first question of the study is concerned, the researcher embarked upon discovering the relationship between each task and the listening comprehension of the EFL learners. The results obtained from the four paired t-tests rejected the first null hypothesis for the three tasks of "matching, labeling and form-filling," and it was verified for the "selecting" task. This means that there was a significant relationship between the first three tasks and listening comprehension; as a result of their application, the listening comprehension of the participants improved. On the other hand, no such relationship was observed between the task of "selecting" and listening comprehension. The participants did statistically better in the post-test on these three tasks and from the researcher's point of view that might be due to the following reasons:

Task input

Prabhu (1987, p. 86) noted that the students in the Communicational Teaching Project (beginner learners in Indian secondary schools) found tasks with an oral input easier than tasks presented in writing. According to Ellis (2003, p. 222), tasks involving pictorial input were easier to process than those that involved written or verbal input, as they made no demands on the learners' linguistic resources. Task types like "matching, labeling and form-filling" that involve pictures and diagrams provided learners with more comprehensible input. The participants of this study, also, accomplished these tasks more successfully and with a greater amount of improvement in comparison with the "selecting" task, which was presented through written inputs. So it was concluded that tasks of the same type with the same input features would have the same effect (the improved listening comprehension) on the participants' performance.

Context-dependency of the tasks

Another possible reason for the students' improvement on the tasks of "matching, labeling and form-filling" might be attributed to the dependency of these task types on the context. Robinson (1995) pointed out that tasks supported by visual information in some form are generally easier to perform than tasks with no such support. Nunan (1989, p. 86) also noted that tasks supported by photographs, drawings, tables, and graphs are easier to understand. The results showed no improvement on listening comprehension as a result of students' exposure to the task of "selecting," and it might be due to the fact that the task was context-free. However, it should be mentioned that the research to date has failed to show conclusively that tasks involving displaced reference are more complex than those involving contextually supported reference.

Cognitive effect of task outcome

Prabhu (1987, p. 87) stated that one of the rationales for choosing task-based syllabuses is that they encourage the engagement of learners. He believed that tasks established a reasonable challenge and were cognitively motivating, as accomplishment would provide learners with a sense of achievement. Prabhu's classification of tasks rested on an account of the kinds of cognitive operations that underlie the actual performance of different kinds of tasks. It was based on the premise that using language for doing or completing a project-like task fostered acquisition—a premise that is certainly intuitively appealing. Ellis (2003, p. 214) supported Prabhu's claim but considered it as an untested proposal. He stated that in the case of project-oriented tasks, where a single outcome was required in addition to a sense of security that might arise as a result of knowing that there was a definite answer to a task, language learners might show much satisfaction at the end of successful accomplishment of these types of tasks.

In his account of the Communicative Teaching Project, Prabhu (1987, p. 51) introduced project-oriented tasks and suggested that the final product of these types of tasks was of a special type – a completed chart, diagram, table or form, with a unique penetrating cognitive effect on learners' internal feelings. Skehan (1998, p. 107) asserted that although task accomplishment always lead to a sense of satisfaction, the completed outcome of project-oriented tasks caused much more motivation and satisfaction.

The researcher, himself, also observed that when the participants performed the three tasks of "matching, labeling and form-filling" (which fall in the category of "project-oriented" tasks, as opposed to the "selecting" task, and achieved a satisfactory outcome) they became more motivated to continue and to perform several more tasks of the same type.

Ellis (2003, p. 285), on the other hand, differentiated between the task of "selecting" and other tasks of the same type as their tests sought to measure the specific abilities required to perform a task, but their claim to be task-based was less obvious as they did not incorporate actual tasks in their test design.

Classroom exercises of the four tasks and their relative position in the general framework of task-based tests

Baker (1989) introduced a general framework to pinpoint the essential characteristics of TBA (task-based assessment). This way, he distinguished between two methods for the accomplishment of TBA. Baker believed that a general distinction could be made between system-referenced tests and performance-referenced tests. As Baker put it:

- - System-referenced tests are used to provide information about language proficiency in a general sense without reference to any particular use or situation.

- - Performance referenced tests, in contrast, seek to provide information about the ability to use the language in specific contexts. (p. 10)

Arguably, communicative tests need to be both (McNamara, 1996). Ellis (2003, p. 284) believed that system-referenced and performance-referenced tests could both be more or less direct/indirect. This second distinction concerned the relationship between the test performance and the criterion performance. Direct tests are based on a direct sampling of the criterion performance. Such tests are holistic in nature and aim to obtain a contextualized sample of the subject’s use of language. The measure of proficiency obtained from such tests is not an integral part of the subject’s performance but has to be derived from it, e.g., by obtaining an external rating. Indirect tests are less contextualized and, arguably, therefore more artificial. Such tests are based on an analysis of the criterion performance in order to obtain measures of the specific features or components that comprise it. They seek to assess proficiency by means of specific linguistic measures, which are obtained from the test itself.

Baker (1989, p. 13) mentioned that the test of the "selecting" task (a listening comprehension test where subjects are asked to listen to a contrived mini-lecture and then answer a number of multiple-choice questions to demonstrate their comprehension) falls somewhere between the two dichotomies. He consequently emphasized that the distinction between system-referenced and performance-referenced and between direct and indirect methods of assessment represent continua rather than dichotomies.

Ellis (2003, p. 286) pointed out that the test of the "selecting" task is obviously performance-referenced, but it probably lies somewhere between the direct and indirect kinds. He claimed that it involves language processing of the real-world kind (i.e., listening to a lecture) and in this respect is direct. However, the subject’s performance is measured indirectly by scoring the answers to the questions. In this respect it differs from direct tests where the measure of the subject’s performance is not incorporated into the task itself but must be derived by an assessor separately through observation or analysis of the performance itself.

The above-mentioned unique characteristics of the "selecting" task accounted for the difference in comparison with the other three tasks in the present study. With reference to these arguments, the researcher concluded that the different behavior of the participants on this specific task might be due to the individual features and the specific position of the "selecting" task among other types of tasks.

Questions involving picture cues

According to Madsen (1983), these types of listening comprehension questions allowed students to benefit from several advantages:

- - There is no need to read the choices, as they are not textual.

- - The students will have a better control over the items of the whole exercise of a given task. (p. 135)

As previously mentioned in the methodology section of the study, Cameron (2000) recommended some strategies for a successful performance on each type of the task-based listening comprehension questions and achieving the best possible results. One of these strategies is that students must be encouraged to examine the whole exercise of the task before listening to the taped text and embarking upon answering the items. He considered this strategy very useful since it could help students to predict the topic of the text in advance and to look for what they needed to perform the task during the stage of listening to the tape.

As far as the second advantage of photographic questions is concerned, the three tasks of "matching, labeling and form-filling," designed to be accompanied by photos, let the participants grasp the idea of the task just with a single look. The researcher, accordingly, might assign the participants' different performance on the task of "selecting" to the structure of the task in question as it lacked any picture cues.

Harmer (2001, p. 234) also suggested that pictorial task-based exercises provided students with the ability of quick prediction and the creation of expectations. He advised teachers to incorporate such a pictorial materials into the class listening activities.

One of the Cameron's (2000) recommended strategies of task fulfillment was "prediction of the theme" of the taped conversation, and Harmer (2001) believed that pictorial exercises would make this prediction much more feasible.

In conclusion, there might be a direct relationship between the structure of the question and the ease of the task accomplishment, as some structures would enable learners to overcome the possible troubles in prediction of the theme and in completion of the task procedures.

The relationship between task and the participants' level of language proficiency

As far as the second question of the study is concerned, the researcher, based on the results of the participants' performance on each task in each level of language proficiency, demonstrated the hypothesis of the suitability of each specific task for each of the levels of language proficiency. The results obtained from the twelve paired t-test showed that from among the four tasks of the study only the "selecting" task did not correspond to the three levels of language proficiency, and the task of "form-filling" was not suitable for the advanced level. Again, except for the results of the "form-filling" task in the advanced level that might be due to the procedural reasons, the participants of all levels did statistically better in the post-test on the three tasks of "matching, form-filling and labeling." The participants (in the three levels of language proficiency) showed no improvement over the task of "selecting" in the post-test. So there was no correspondence between the task in question and the participants' level of language proficiency. The researcher concluded that this task is not suitable for all levels of language proficiency and that might be due to the fact that this task is completely different in nature from the other three tasks. From the point of view of the researcher, the unique nature of this task results from its distinctive features listed above.

Conclusion

Implementing aural task-based materials in the language classroom exposed ESL students to real-language use from the beginning of language study. The materials reflected a naturalness of form (Rogers & Medley, 1988). Generally speaking, according to the obtained results, the listening-comprehension skill in EFL students tended to improve through exposure to task-based input. Specifically, the three types of "matching, labeling, and form-filling" not only affected the listening comprehension of the participants and improved it but also corresponded to the three levels of language proficiency and proved to be suitable for all the participants at all levels.

References

Baker, D. (1989). Language testing: A critical survey and practical guide. London: Edward Arnold.

Briggs, S., Dobson, B., Rohlck, T., Spaan, M. & Strom, E. (2001). Examination for the certificate of proficiency in English. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cameron, P. (2000). Prepare for IELTS: The IELTS preparation course. Sydney: University of Technology.

Chastain, K. (1988). Developing second language skills: theory and practice. (3rd ed.). Florida: Harcourt brace Jovanovich Publishers.

Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and education. (1966 edn). New York: Free Press.

Dirven, R., & Oakeshott-Taylor, J. (1985). Listening comprehension. Language Teaching 18, 2-20.

Doughty, C. & Pica, T. (1986)." Information-gap" tasks: do they facilitate second language acquisition? TESOL Quarterly 20 (2), 305-325.

Dunkel, P. (1986). Developing listening fluency in L2: theoretical principles and pedagogical considerations. The Modern Language Journal 70, 99-106.

Ellis, R. (2003). Task-based language learning and teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Farhady, H., Jafarpur, A. J., & Birjandi, p. (2000). Testing language skills from theory to practice. Tehran: SAMT Publications.

Harmer, J. (2001). The practice of English language teaching. Harlow: Longman Publications.

Herron, C. A., & Seay, I. (1991). The effect of authentic oral texts on student listening comprehension in the foreign language classroom. Foreign Language Annals 24, 487-495.

Jacobs, G. (1998). 'Cooperative learning or just grouping students: the difference makes a difference' in W. Renandya and G. Jacobs (eds.): Learners and language learning (pp. 145-171). Singapore: SEAMEO.

Jean, I. & Hahn, J. (2006). Exploring EFL teachers' perception of task-based language teaching: a case study of Korean secondary school classroom practice. Retrieved 8, 6, 2007 from: http://www.asian-efl-journal.com/March06_ijj&jwh.pdf.

Lightbown, P. (1992). 'Can they do it themselves? A comprehension-based ESL course for young children' in R. Courchene, J. St. John, C. Therrien, and J. Glidden (eds.): Comprehension-based language teaching: Current trends. Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press.

Littlewood, W. (2004). The task-based approach: some questions and suggestions. ELT Journal 58 (4), 319-327.

Lund, R. J. (1990). A taxonomy for teaching second language listening. Foreign Language Annals 23, 105-115.

Mackey, A. (1999). Input, interaction and second language development: an empirical study of question formation in ESL. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 21, 557-87.

Madsen, H. S. (1983). Techniques in testing. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

McNamara, T. (1996). Measuring second language performance. London: Longman.

Morley, J. (1990). Trends and developments in listening comprehension: theory and practice. In J. E. Alatis (Ed.), Georgetown University round table on languages and linguistics 1990: Linguistics, language teaching and language acquisition: the interdependence of theory, practice and research (pp. 317-337). Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

Nunan, D. (1989). Designing tasks for the communicative classroom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nunan, D. (1999). Second language teaching and learning. Boston: Newbury House Publication.

Paulston, C. B., & Bruder, M. N. (1976). Teaching English as a second language: Techniques and procedures. Cambridge, MA: Winthrop.

Prabhu, N. S. (1987). Second language pedagogy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Richards, J. C. (1983). Listening comprehension: approach, design, procedure. TESOL Quarterly 17, 219-240.

Richards, J. C. & Renandya, W. A. (2002). Methodology in language teaching: An anthology of current practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rivers, W. M. (1981). Teaching foreign language skills. (2nd ed.). Chicago: Universityof Chicago Press.

Robinson, P. (1995). Task complexity and second language narrative discourse. Language Learning 45, 99-140.

Rogers, C. V., & Medley, F. W. (1988). Language with a purpose: using authentic materials in the foreign language classroom. Foreign Language Annals 21, 467-478.

Scrivener, J. (1994). Learning teaching. Oxford: Macmillan Heinemann English Language Teaching.

Skehan, P. (1998). A cognitive approach to language learning. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ur, P. (1984). Teaching listening comprehension. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Widdowson, H. (1990). Aspects of language teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wing, B. H. (Ed.). (1986). Listening, reading, writing: Analysis and application. Middlebury, VT: Northeast Conference on the Teaching of Foreign Language.

Appendix

Models of the Four Task Types

I. Matching

Listen to the taped descriptions of the people in the illustrations below, A to H. Match the description to the figure.

II. Form-filling

Listen to the dialogue and fill out the application form while you listen.

III. Labelling

Library Tour - Listen to the guided tour commentary and label the places marked. Choose from the box below. Write the appropriate letters A to J on the diagram.

IV. Selecting

Circle the appropriate letter.

- The speaker works within the Faculty of

- Science and Technology

- Arts and Social Sciences

- Architecture

- Law

- The Faculty consists firstly of

- subjects

- degrees

- divisions

- departments

- The speaker says students can visit her

- every morning

- some mornings

- mornings only

- Friday morning

- According to the speaker, a tutorial

- is a type of lecture

- is less important than a lecture

- provides a chance to share views

- provides an alternative to group work

- When writing essays, the speaker advises the students to

- research their work well

- name the books they have read

- share work with their friends

- avoid using other writer's idea

- The speaker thinks that plagiarism is

- a common problem

- an acceptable risk

- a minor concern

- a serious offence

- The speaker's aims are to

- introduce students to university expectations

- introduce students to the members of staff

- warn students about the difficulties of studying

- guide students round the university

- The subjects taken in the first semester are psychology, sociology, history, and

- politics

- economics

- chemistry

- mechanics

|