Taiwan’s Quest for Self-Determination and the Language of Resistance:

An Analysis of Social Unrest in Taiwan.

Scott Beck

University of Pittsburgh

Abstract

Taiwan has a history full of oppressive rulers and people who resisted their oppression. During October to December of 2008, widespread protests of government intervention in civil society showed that this struggle is not yet finished. This paper analyzes those protests, particularly as they pertain to the Wild Strawberry Student Movement. Key concepts used in this analysis are an action-centered conceptualization of culture as a tool-kit, a narrative of unfolding, and a language of resistance.

"It is the job of thinking people not to be on the side of the executioners." ~Albert Camus

Introduction

This paper explores the social upheaval that occurred in Taiwan from October to December of 2008. For this analysis, I view culture as a “tool-kit” of symbols, stories, rituals and worldviews, which people use in varying configurations to solve different kinds of problems.1 The appearance of these tools is in many respects born of necessity; in order to understand the raison d’être of any particular tool we must look at the historical and social conditions that necessitated its existence as these conditions act like a “culture” in a petri dish, out of which a multiplicity of tools may emerge. I will refer to these tools as the language of resistance, or the slogans, chants, songs, and rituals that provide both inspiration and solidarity within a social movement. I will also consider the importance of a sense of history, or what has been termed a narrative of unfolding.2 Such a narrative includes not just a sense of us as individual historical actors, but also a sense of being part of something larger than ourselves, a collective sense of history as constituting a movement, a people, a nation, and the destinies thereof.

One of the central tensions of Taiwanese society is a contested view of Taiwan’s destiny among the various factions in Taiwanese politics, primarily between the two main rival parties: the Kuo Ming Tang (KMT) and the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). A perfect example of this rivalry was to be found in the Taiwanese entourage’s awkward visit to the US for Barack Obama’s inauguration. The entourage consisted of delegates from the KMT, the DPP, and the Taiwanese government, presumably the neutral party meant to maintain peace between the rivals.3 While addressing a banquet of Taiwanese living in the US, a KMT representative said, “Taiwan is not a country, but the Republic of China is. This matter however should not come between us for after all, we are all Chinese.” This statement so irritated the DPP representative Annette Lu, the former Vice President, that she refused to attend a later event held at the Taipei Economic and Cultural Representative Office (the de facto Taiwanese embassy). Mrs. Lu would have said just the opposite: Taiwan is a country and we are all Taiwanese.

Before conducting my analysis, I will need to give a brief synopsis of Taiwanese history so that the reader may get a sense of the narrative of unfolding which is contested and the discourse contained therein. The historical synopsis will also help to illustrate a point social theorist Michel Foucault made regarding the analysis of discourse: “The question posed by language analysis of some discursive fact or other is always: according to what rules has a particular statement been made, and consequently according to what rules could other similar statements been made? The description of the event of discourse poses a quite different question: how is it that one particular statement appeared rather than another?”4 The latter question that Foucault poses is one I hope to answer in this paper as I trace the historical origins of statements that appeared during the protests, and also the social/historical conditions that provided for their eventual mainstream emergence.

I also hope to show that discourse and action are intricately bound—one informs the other. Any language of resistance within a continuing discourse is underpinned by the activism which made its mainstream circulation possible; during Taiwan’s post-WWII history, the statements that could or could not appear were determined by the KMT’s “cultural policy,”5 which was designed to not only indoctrinate native Taiwanese into viewing themselves as Chinese but also to control the flow of information, or what the KMT termed “poisonous thoughts,” which contained discourse on subjects such as class struggle, democracy, or Taiwan independence.

History and Context

After the end of WWII, as part of the Japanese Instrument of Surrender, Taiwan was relinquished from Japanese colonial rule and placed under Chinese rule. China was then the Republic of China and ruled by the KMT, headed by Chiang Kai Shek. In 1945, as nearly 12,000 troops arrived in Taiwan, the KMT were warmly greeted by Taiwanese hopeful that KMT rule would be better than Japanese rule. They were to be sorely disappointed. Just over two years later, the 228 Massacre occurred. Twenty to thirty thousand Taiwanese died in an uprising that was instigated by government corruption.6 This was to be a pivotal event in the formation of a Taiwanese narrative of unfolding as they came to see themselves as a group oppressed by the KMT, who were often viewed as foreign conquerors in the same way as the Japanese.

Also during that time the Chinese Civil War was being waged between the KMT and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). As it became increasingly clear that Chiang Kai Shek was going to lose the war, he prepared Taiwan for his inevitable retreat by declaring Martial Law on May 20 of 1949—the official premise being that it was necessary in order to curtail the threat of Communism, a threat that would be invoked repeatedly to justify other harsh measures. On December 7, 1949, the KMT retreated to Taiwan, along with 600,000 troops and over a million Chinese as the KMT central government set itself up in Taipei, Taiwan’s largest city. With the arrival of the KMT came the White Terror, a period of extreme repression that brought with it a series of abrogations that had cultural as well as political consequences.

Among the abrogations put in place were a ban on private radio stations, which lasted until the early 1990’s; a ban on men’s “strange apparel,” which were fashions showing relatively new styles or evidence of individualism; a ban on overseas tourism and visits to overseas relatives; compulsory registration of radio sets and a monthly charge of 10 New Taiwan Dollars for the privilege of owning a radio; a ban on newspapers not officially sanctioned by the state (lasted until January 1, 1988); a ban on middle school student’s long hair for both men and women; a “General Inspection of School Books,” which required elementary schools to inspect all books for evidence of opposition to state policy or the encouragement of class struggle; a ban on Taiwanese history being taught (only Chinese history was to be taught); a ban on local languages, Hoklo (Taiwanese), Hakka, and Aboriginal tongues; and a ban on Taiwanese folk songs and popular songs inclined to social realism.7

Such abrogations were repeatedly revised and made more repressive, and new ones were frequently installed up until, and shortly after, the death of Chiang Kai Shek’s son, Chiang Ching Kuo, in 1988. Although Chiang junior lifted Martial Law in 1987, change did not come about overnight. With the ascendancy of Taiwan’s first native born president, Lee Teng-hui, in 1990, the pace of change would accelerate throughout the 1990’s, leading to full democratization and the first direct Presidential election, won by Lee in 1996. In 1997, Taiwan was listed as a “free country” by Freedom House, a human rights NGO based in the United States.

The reasons for this transformation are numerous and complex and include the democratic principles written into the ROC constitution by founder Sun Yet Sen,8 massive domestic pressure on the KMT for change, particularly from the marginalized rural and urban working classes,9 and international conditions as the KMT felt continual pressure to liberalize in order to gain favor and support from Western countries that were leaning towards closer ties with Communist China.10

In addition to the preceding historical account, there are other key factors that are essential for understanding the current paradoxes and contentions that still remain in Taiwanese society and culture. First, the People’s Republic of China claims that Taiwan is part of its territory and currently has anywhere from 800 to 1000 missiles aimed at Taiwan, threatening to use them should the country formally declare independence. Second, as of May 2008, the KMT was democratically elected back into power after eight years of rule by the Democratic Progressive Party. Ever since the party fled China to establish itself in Taiwan and up until Lee Teng-hui took power, the KMT maintained that the ROC was the sole legitimate China, and it was their full intent to take back the “mainland” by force. Lee however took up the position of “Two Chinas,” or in other words, two separate countries across the Taiwan Strait, and the DPP viewed Taiwan as a country completely distinct from China; the current KMT, led by President Ma Ying-jiao, has re-adopted the “One China” orthodoxy as its official policy and has nebulously suggested that the ROC is still the legitimate China; they have also established a cozy relationship with the CCP, and have rapidly, and rather surreptitiously, increased economic ties with China, a situation that has many Taiwanese worried about an impending “sell-out,” a situation which has sparked numerous protests. As in the past, the protests often gathered in the public area in front of Chiang Kai Shek Memorial Hall (also referred to as Taiwan Democracy Memorial Hall).

Shortly after it was built in the late 1970’s to honor Taiwan’s late dictator, Chiang Kai Shek Memorial Hall soon became the site of massive protests, an obvious contradiction to its intended use. The large public area surrounding the memorial was dubbed Memorial Square, which also included centers for traditional Chinese culture such as the National Opera House and the National Concert Hall, all intended to express the “spirit of Chinese Culture.” In a profound example of just how much Taiwanese politics had changed, in June of 2007 the huge Chinese characters which hung above the main gate of the complex and read “Great Mean, Perfect Uprightness,” a reference to the late dictator, were replaced by the DPP led government with characters reading, “Liberty Plaza,” no doubt meant to express the spirit of Taiwanese self-determination. The controversial move, made by then President Chen Shui-bian, is an example of a statement many Taiwanese never thought they would see and was made possible only by the activism of past struggles.11

As previously mentioned, since the KMT returned to power, concessions have been made by the government that many Taiwanese believe could compromise their national integrity. These worries came to a boil in November of 2008 after a visit by Chen Yunlin, the first high-level visit by a Chinese representative since 1945. After the harsh police crackdown on the protests which accompanied Yunlin’s visit, a student movement called the Wild Strawberries began in response and made three demands: an apology from President Ma Ying-jiao, the resignation of the National Police Agency General-Director, and an amendment to the Parade & Assembly law (installed shortly after the lifting of Martial Law), which would remove the stipulation requiring a permit for public protest. The student movement began in front of the Legislative Yuan, the Taiwanese “congress.” After the police expelled them from that location, the Wild Strawberries reconvened in Liberty Square, which would become their base of operations. As will be demonstrated later, the movement utilized many of the same tools that were used by the activists during the 70s, 80’s, and 90’s.

Methodology

Data for this paper were taken from my own pictures, videos, and conversations with locals acquired during October of 2008 to early January of 2009. Blogs and YouTube videos were also instructive in putting together the pieces of the successive waves of protest that typified the time during and immediately following Chen Yunlin’s visit. (Unless otherwise indicated, all data are taken from my first hand observations.) It should also be mentioned that I was not necessarily in Taiwan as an ethnographer, but as an English teacher, and acted as a participant/observer and supporter of the protesters, hence not really a neutral observer. Not being neutral however allowed for more candid interactions with the locals, who were very eager to confide their viewpoints and concerns. Whatever might have been lost in objectivity was gained in insight into the innermost feelings of Taiwanese concerned about the direction their homeland was headed.

True to the self-reflexive turn in social ethnography, I will state very clearly that my position as a foreigner in the midst of this social upheaval was one with some degree of privilege. During the protests, I was told repeatedly that the police would most likely not harm me and that my presence might even cause them to be “more conservative” in the way they handled protesters. For example, while living in a hostel several blocks from Liberty Square, I was able to monitor the student sit-in online and in real-time via the Wild Strawberries ’ page on JustinTV, a podcast website where there was live streaming of the sit-in proceedings. While watching this at my hostel, I witnessed some commotion between the police and students. Because of my close proximity, I was able to run over to the site in just over five minutes. Once there, I turned on my digital camera, set to take video, and recorded what was one of the many arguments between the students and the police as the students tried to gradually re-assemble their sit-in after they were forcefully evicted from Liberty Square—to be explained later. It was a cold night with a chance of rain, and the student’s were setting up a tarp for shelter. As had happened many times before, after a lengthy debate the police left after giving the students a written warning. I was later thanked by an older woman, not a student but one of the many locals that frequently joined the Wild Strawberry sit-in. She was quite convinced that the police would be on their best behavior when foreigners were present and thought it would be a great idea if foreigners could always be present. Although that was not necessarily possible, I made a point of it to be present as often as I could.

Taiwan’s Language of Resistance

Under the perceived threat to the nation’s self-determination, the past struggles for democracy and human rights were invoked, and the symbols and messages born in those struggles were used as a language of resistance. During the student sit-in, and prior to the forceful, yet temporary, removal of the students from the location, a survey of Liberty Square would have shown the presence of the past struggles as well as an indication of the hopes and dreams of a new generation of Taiwanese.

On a weekday afternoon, what would normally have been a placid Liberty Square, with students in class and workers at work, symbols of freedom, democracy, and human rights were front and center. Three large metal cages stood side by side, containing chairs where students had previously sat in dramatic repose. One cage contained a sign that read, in Mandarin, “Human Rights.” Attached to the outside of a different cage was a sign bearing the English word “Freedom.” The next cage contained a sign that read, in both English and Mandarin, “23 Million Taiwanese Decide the Future of Taiwan.” Sitting in front of each cage was a bouquet of flowers.

As previously mentioned, such statements have their origin in Taiwan’s previous struggles. The ideals of freedom, human rights, democracy, and self-determination can be traced back to intellectuals such as Lei Chen and Peng Ming-min. Due to his ardent opposition to Communism, Lei was actually a member of the KMT inner circle until his expulsion in 1955. His magazine, Free China, advocated democracy and freedom of speech and was banned from publishing in 1960. Peng was instrumental in the advancement of Taiwanese self-determination and was the author of the “Declaration of Taiwan People’s Self-Salvation” and the “One China, One Taiwan” theory. In 1964, he had printed flyers and was preparing to circulate them throughout the island, but before he could distribute them he was arrested and given a heavy sentence.12 During the recent protests, one of the most popular signs read, “One Taiwan, One China.” However, in an apparent trick on the protesters by a KMT supporter, the English part of the sign read, “On Taiwan, One China,” with the “e” having to be inserted later.

Another prominent structure found in Liberty Square was the “Human Rights Tower,” which was nearly 20 feet in height and modeled after an aboriginal design. Each level of the bamboo tower contained a colorful horizontal banner, two of which read in English, “Stop State Violence,” and “Stop Human Rights Violations.” Stretching vertically from the top of the tower to the ground were banners that read, in Mandarin, “Revise the Parade & Assembly Law.” A ladder that hung on one side of the tower led to the top level that could act as a look out. During their eviction, after which the Human Rights tower was destroyed, one of the students had climbed to the top level and began chanting “He Ping (peace)” through a megaphone, as if elevating “peace” above state intervention.13 In general, during Taiwanese political assemblies, the omnipresence of symbols and statements of human rights elevate them to the level of the sacred, and they are seen as a universal ideal that serves to shield the populace against state abuse of power.

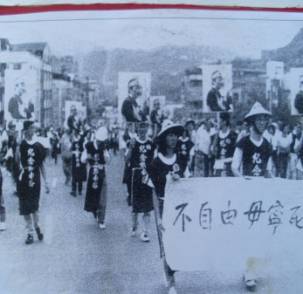

It was not just the students that had joined the sit-in. Several veterans of Taiwan’s first wave of democratization, known as the “Deep Green Coalition,” (green being the color of the DPP, whereas the blue is the color of the KMT) were also present. Propped up by an easel, a large square of red construction paper bore pictures that told their story; written at the top was “Walk our Taiwan Road,” a reference to their narrative of unfolding. One picture depicted a march organized by the Wild Lily student movement,14 which in 1990 held a sit-in outside CKS Memorial Hall in what was then called Memorial Square; the students marched holding signs bearing a picture of Cheng Nan-jung, also called Nylon Deng, who is regarded by many as Taiwan’s first martyr of democracy; in 1989, he had immolated himself in protest of the KMT’s attempts to incarcerate him for publishing the Freedom Era Magazine, which advocated freedom of speech, direct democracy, and contained a Constitution for the Republic of Taiwan. The students in the front of the march held up a banner that read (in Mandarin), “Without freedom, I’d rather die.” Cheng Nan-jung’s remains an iconic figure, and his image could also be found in the many marches that occurred after the Yunlin visit.

Another feature of the sit-in was the many open-faced wooden cabins that housed anything from a student painting of Che Guevara to a make-shift shrine that had been built for Human Rights in the tradition of paying homage to a deceased family member. With handcuffs placed alongside an orange, meant for the benefit of the deceased relative, this bricolage was a sarcastic statement on how during the Chen Yunlin visit it was if human rights had died; it also served as a testimony to how sensitive the Taiwanese had become to even a temporary curtailment of their civil rights.

Among the temporary abrogations put in place by the Central Police Agency were the shutdown of major highways to prevent more people from joining the protest, prohibiting people from waving the ROC national flag or chanting slogans such as “Taiwan does not belong to China,” and the closure of a music store (situated near the hotel where Yunlin was staying) that played “Songs of Taiwan,” a collection of patriotic songs.15 These measures were meant in part to prevent Chen Yunlin from having to see or hear anything that suggested Taiwan was not a part of China. Although the primary goal was simply to keep Yunlin safe, the repressive measures inflamed into riots what might have otherwise been impassioned, yet largely peaceful expressions of national identity.

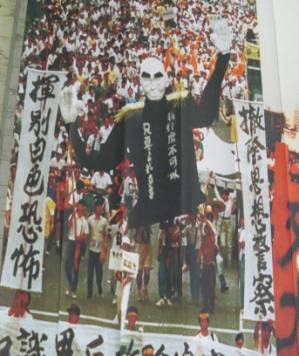

The cul de sac of the movement was the December 9th march in defiance of the Parade & Assembly Law. The students did not petition for a permit but merely informed the police of their intentions. The peaceful march itself was very well organized and included not just students, but thousands of Taiwanese from all walks of life. Among the statements which appeared were slogans such as “I stand for Human Rights,” and “Stick It To the Man,” as well as non-verbal statements such as an effigy of Ma Ying-jiao, reminiscent of effigies past when Chiang Kai-shek was the center of ridicule. A business card created in promotion of the march featured an image of Jules Joseph Lefebvre’s painting La Verite, with the top of the torch bearing a strawberry. Similar symbols of freedom, such as the Statue of Liberty, are common in Taiwan.A few days after the march, and only hours after Ma Ying-jiao endorsed two international human rights documents at an Asian Democracy and Human Rights event commemorating Human Rights Day, the police forcefully dispersed Tibetan refugees from Nepal and India that had also congregated in Liberty Square, then the students; they were both separated into groups and bused to Taipei City outskirts.16 During the first moments of the struggle, a student posted the following, in both English and French, to the Wild Strawberry English website: “It is time for the Minuteman! Arise, children of the Fatherland, the day of glory has arrived! Against us the tyranny’s bloody banner is raised.”17 This statement recalls not only the American, but also the French Revolution, and demonstrates the considerable influence Western thought has had on Taiwan’s language of resistance and the extent to which it has altered the consciousness of many Taiwanese. At a different point, the students began to sing “We Shall Overcome,”18 a song sung during the American Civil rights movement, indicating cross cultural appropriation of a will to self-determination. During resistance any tool that is relevant to the cause can and will appear in the field of discourse.

The following day, the students, as well as the Tibetans, returned to Liberty Square. One female student told the crowd that had gathered in the evening, “It is useless for the police to come back again and again, because we will come back again and again.” Over the weeks that followed, the students began to rebuild their sit-in while under 24-hour police surveillance. Yet shortly after New Year’s Day, the sit-in ended; the students had made the decision to move their operations to a nearby office, which they called “Strawberry House.”

Conclusion

In Eastern societies, a healthy respect for authority is very often well regarded. A column in the China Post, entitled “Back to school, Wild Strawberries” offered this advice to the students: “The best way to keep harmony in a country and rid it of any unrest and woes that may befall its people, according to the time-honored Confucian doctrine, is for everyone to play their roles dutifully.”19 However, there is very little Confucian doctrine in Taiwan’s language of resistance. On the first night of the student sit-in, in front of the Legislative Yuan (Taiwan’s Congressional Building), a National Taiwan University Professor20 explained the very conditions under which this doctrine breaks down: “The state has stretched its evil hand into civil society where democracy has struggled for 30 years.” This situation presents the dilemma expressed on the Taiwanese blog Free Speech in Taiwan: To Obey or not to Obey, This is the Question—if citizens do not have to conform to the law when they see it as illegitimate, what authority would the law still retain in its ruling over members of society?”21

Such a dilemma invokes a language of resistance, which has as its basis all previous struggles for human rights, freedom, and self-determination, whether they occurred in Taiwan or the West. In such a tool-kit, social actors find the necessary inspiration and guidance to make that choice: To Obey or Not to Obey. Where there is that choice, you will also find a language containing a blueprint, drawn up during previous struggle but also including an assessment of contemporary conditions, for the continued march towards self-determination.

Bibliography

Action Statement from the Wild Strawberry Movement. November, 2008 <http://taiwanstudentmovement2008.blogspot.com/2008/11/protest-statement.html>

Brown, Melissa J. Is Taiwan Chinese? Berkley: University of California Press, 2004

Edles, Laura Desfer. Cultural Sociology in Practice. Malden, Mass: Blackwell Publishers, 2002

Foucault, Michel. The Archaeology of Knowledge. London: Tavastok, 1972

Harrell, Stevan; Huang, Chun-chieh. Cultural Change in Postwar Taiwan. Boulder: Westview Press Inc, 1994

Hung, Joe. “Back to school, Wild Strawberries,” China Post. November 17, 2008

The Road to Freedom: Taiwan’s Postwar Human Rights Movement, Taipei: Haiwang Printing Company, 2004.

Roy, Denny. Taiwan: A political History. London: Cornell University Press, 2003

Yang, David. “Classing Ethnicity: Class, Ethnicity, and the Mass Politics of Taiwan’s Democratic Transition.” World Politics 59 (July 2007), 503-538.Appendix: (all photos by Author)

The Wild Strawberries marching (left). The Wild Lilies marching with photos of Cheng Nan-jung. The banner reads, “Without freedom, I’d rather die.” (right).

An effigy of Ma Ying Jiao (left) An effigy of Chiang Kai Shek. Photo taken inside Taiwan Democracy Memorial Hall (aka Chiang Kai Shek Memorial Hall) in January of 2007 (right)

Wild Strawberry March (left) In memoriam of human rights (right)

A woodcutting, from 90’s era protests, appropriating the “black power” fist. The heading reads, “Give me civil rights.” (right) A t-shirt that could be found during protests in the Autumn of ‘08. It reads, “Taiwan crisis. Mobilize all the people.” (left)Footnotes

1^ Edles, Laura Desfer. Cultural Sociology in Practice. Malden, Mass: Blackwell Publishers, 2002 p. 221-222

2^ Brown, Melissa J. Is Taiwan Chinese? Berkley: University of California Press, 2004 p.221

3^ For some time it seemed as if the DPP and KMT would have to travel separately due to their ideological differences.

4^ Foucault, Michel. The Archaeology of Knowledge. London: Tavastok, 1972. p. 14

5^ Harrell, Stevan; Huang, Chun-chieh. Cultural Change in Postwar Taiwan. Boulder: Westview Press Inc, 1994.p. 22

6^ The Road to Freedom, Taipei: Haiwang Printing Company, 2004. p. 100

7^ Ibid, p. 29- 30.

8^ Roy, Denny. Taiwan: A Political History. London: Cornell University Press, 2003. p. 83

9^ Yang, David. Classing Ethnicity. World Politics 59 (July 2007), 503-538. p.509.

10^ Roy, p. 100

11^ On July 20, 2009, the placard that the DPP had installed on Chiang Kai Shek Memorial Hall, reading “Taiwan Democracy Memorial Hall,” was removed and the original placard was re-installed by the KMT run government. There were however no plans to replace “Liberty Square” with the original characters on the main gate.

12^ The Road to Freedom, p. 109

13^ Youtube. < http://taiwanstudentmovement2008.blogspot.com/2008/12/20-mins-video-clip-on-1211-incident.html>

14^ This student movement met with more fortunate circumstances as then President Lee Teng-hui was receptive to their demands for democratic reform. The Wild Strawberries have had no such luck with Ma Ying Jiao.

15^ Action Statement from the “Wild Strawberry Movement” <http://taiwanstudentmovement2008.blogspot.com/2008/11/protest-statement.html>

16^ It was later reported by the students that the reason for the dispersal was the aid the students had given the refugees, such shelter in the wooden structures they had built along with blankets to keep them warm.

17^ <http://taiwanstudentmovement2008.blogspot.com/2008/12/police-officer-is-demanding-that-they.html>

18^ Youtube < http://taiwanstudentmovement2008.blogspot.com/2008/12/20-mins-video-clip-on-1211-incident.html>

19^ Hung, Joe. “Back to school, Wild Strawberries,” China Post. November 17, 2008.

20^ In June of ’09, this professor, Lee Ming-tsung, was indicted for violating the Parade and Assembly Law.

21^ <http://freespeechintaiwan.wordpress.com/2008/11/13/to-obey-or-noto-obey-this-is-the-question/>

|