Cutting the Fat on Healthcare:

An Investigation of Preventive Healthcare and the Fight on Obesity

Maggie Bertucci,

Alex Miller,

Stephen Jaggi,

Steven Wilding,

Brigham Young University

Key words: Healthcare reform, preventive costs, obesity

Abstract

The recently passed Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 summons a $940 billion budget focused primarily on providing health care coverage for every American. In 1965, the government had a similar goal, which led to the implementation of Medicare and Medicaid. Unfortunately, these programs ended up costing ten times what was originally estimated. Perhaps this was partially due to the rising rates of disease in recent years, particularly obesity. In order for the government to stay within its current budgetary limitations and for America to sustain long-term control over its health concerns, we feel that there should be a shift towards more preventive care instead of primarily focusing on reactive care (treating the symptoms). We set out to discover if preventive care is more cost-effective than reactive care, limiting our focus strictly to rising obesity rates and its associated costs. In this paper we summarize the current literature on the subject and discuss both the advantages and difficulties of establishing a more preventive approach toward healthcare. We conclude that prevention would extend quality years of life to more Americans at a lower cost than when primarily implementing reactive care. Our main goal in writing this article is to raise awareness of this potential. To illustrate this, we analyzed three preventive approaches: school-based programs, dietary restrictions, and increased exercise. These three examples are effective at reducing obesity and cost-efficient. Together, they serve as the general framework of preventive care upon which more advanced and specific programs can be discussed.

Introduction

In 2006, America spent 2.1 trillion dollars (an astounding 16% of its gross domestic product) on health care, more than any other country in the world (Marmor, Oberlander, & White, 2009). Even with such spending, over 45 million Americans are uninsured and millions of others are unsatisfied with their current health insurance policies (Marmor et al., 2009). There is little doubt that reform is needed. The recently passed Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 Bill draws on a massive budget ($940 billion) and primarily focuses on covering more Americans with more affordable health care (Henry J. Kaiser Foundation, 2010). Although these goals are commendable, the rising levels of unhealthy and diseased Americans, specifically those with obesity-related illnesses, cast a shadow on the potential of such reforms.

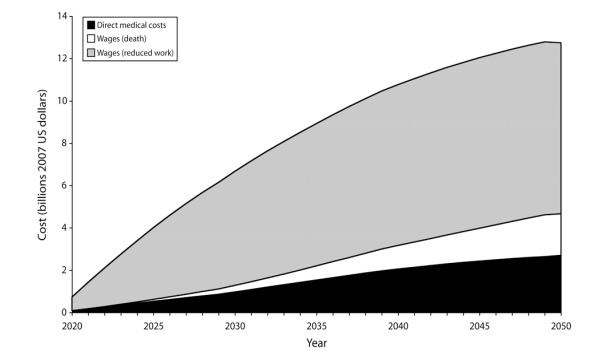

Evidence shows that over-eating is America’s most expensive and dangerous habit, and as such, should be the focus of the government’s preventive action. As of 2008, 65 percent of Americans were considered either overweight or obese, and nearly 10 percent of health expenditures are attributed to obesity-related illnesses (Center for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2010). In 2009, the CDC also showed that obesity-related deaths account for two out of the three leading causes of death in the United States (CDC, 2010, Figure 1).

Figure 1. Actual causes of death, 2009This evidence suggests that many citizens are not exercising responsibility for their health despite demanding rights to healthcare coverage. Such startling health concerns raise questions about whether reforms should focus on providing expanded coverage at better prices or on preventing diseases like obesity and implementing healthier lifestyles. Regardless, while many Americans are concerned with gaining the financial benefits that will allow them to eat, drink, and be merry, rising levels of obesity and sedentary lifestyles have brought about one shocking reality—tomorrow we die.

As U.S. citizens and government officials attempt to come to a mutual understanding about affordable healthcare options, both fail to realize that understanding is never a one-way street. Reducing medical costs is directly related to increasing the number of proactive and healthy individuals. However, the public eye seems to focus solely on the costs of their current insurance premiums rather than the status of their own health. It is this lack of attention on general health and over-emphasis on healthcare that fuels the bulk of America’s healthcare problems. Although the majority of government and public attention is given to reactive, short-term policies regarding healthcare, improving awareness and policy for preventive measures is the best way for America to solve its long-term crisis. We will demonstrate America’s need for a preventive healthcare movement by comparing and contrasting preventive and reactive policies specifically regarding obesity, discussing the need for increased obesity awareness at multiple government and social levels, and exploring the monetary and societal costs associated with implementing preventive action against this growing epidemic. In doing so, we will limit our discussion to primary prevention (avoiding the disease before it occurs). Our goal is to raise awareness about simple, cost-efficient preventive methods that could potentially be implemented into healthcare reform, as well as discuss the many difficulties involved in creating effective preventive policy. An in-depth analysis of current healthcare legislation should be reserved for a separate discussion.

A look at the past

In processing the undertaking facing American healthcare legislators, it is important to remember that the United States government has sought to reform healthcare in the past and has been dissatisfied with the outcome of its efforts. In the Social Security Act of 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson introduced Medicare and Medicaid into the country’s healthcare system (Derthick, 1979). Medicare provides coverage for citizens over 65 years and Medicaid provides coverage for low-income families and individuals. The implementation of these two programs was projected to cost $12 billion (Myers, 1967) in 1990, but actual government spending exceeded $110 billion (Budget, 2010). Even with the onset of inflation, which was undoubtedly accounted for in the original estimate, the government still failed to provide any data that were even remotely accurate.

Perhaps one reason for this gross misestimate was the government’s inability or reluctance to foresee the sharp rise in obesity coming in future years. For example, statistics from the CDC show that from 1950-1970, obesity rates rose only 3.5 percent (National Center for Health Statistics [NCHS], 2002). However, in a later eight-year period from 1980-1988 obesity rates rose 10 percent (NCHS, 2002). Government’s lack of focus on prevention in 1965 led them to underestimate the cost of its reforms by almost $100 billion. This ten-fold fallacy of the past threatens the credibility of today’s healthcare cost projections, especially in light of similar negligence regarding preventive care. With current estimated costs at $940 billion, one can only hope the margin of error for today’s reform is somehow less than it was in the past. In reference to the current cost estimates, The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) recently wrote a letter to Speaker of the House, Nancy Pelosi, stating that, "it is unclear whether such a reduction in the growth rate of spending could be achieved, and if so, whether it would be accomplished through greater efficiencies in the delivery of health care or through reductions in access to care or the quality of care" (Congressional Budget Office [CBO], 2010). Again, the fact that a government office solely responsible for calculating costs of governmental programs is unable to provide reliable data for the current reform creates a sense of fear in many who oppose the direction congress is moving. Regardless of the reliability of current estimates, history has shown that government tends to overestimate the effectiveness of their programs while underestimating their costs. Both government legislators and the American public should keep these facts at the forefront of their minds when judging the severity of the crisis they face.

The balance of preventive and reactive care

Given the vast array of healthcare concerns needing attention and the various parties interested in receiving government financing, the issue of money has become a key area of dispute. America’s political and scientific communities heavily debate where this money should be spent, particularly how much should be partitioned to reactive measures versus preventive measures.

On March 23, 2010, President Obama signed the new health bill that focuses primarily on providing insurance to most Americans, although it does have a small section on preventive strategies. One of the bill’s goals is to “improve prevention by covering only proven preventive services and eliminating cost-sharing for preventive services in Medicare and Medicaid” (Henry J. Kaiser Foundation 2010, p. 32). The preventive services directly referred to in the bill are immunizations, screenings, and additional preventive care approved by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Although proper immunizations and screenings are very important, nothing in the new bill directly addresses the obesity epidemic. Perhaps this topic will be addressed in the bill’s strategy to “establish the National Prevention, Health Promotion and Public Health Council to coordinate federal prevention, wellness, and public health activities” and to “develop a national strategy to improve the nation’s health” (Henry J. Kaiser Foundation, 2010, p. 31). It is important to note that although 65 percent of Americans are either overweight or obese, the government is just beginning to propose a plan of action. Actually, they are not fully proposing a plan, just a plan to make a plan—a mindset all regular dieters can appreciate.

For many who strongly support a more reactive healthcare program, reducing the focus on reactive healthcare measures only means that more people will get sick and fewer people will be readily available to help them. Although these concerns are legitimate, looking at the projected costs of a future America unregulated by health education and self-control highlights the fact that a much larger population would ultimately be negatively affected by a lack of preventive care than would now be affected by rising health costs. In essence, although reactive policy can be effective in addressing immediate health concerns, overtime no amount of reactive policy will be able to combat the excessive health problems plaguing U.S. citizens.

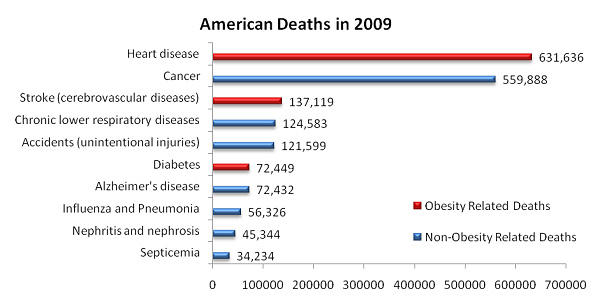

To illustrate the importance of preventive care, one team of researchers conducted an extensive study that projected financial estimates for the years 2020-2050, assuming the rise in obesity continued at its current rate. To accomplish this they divided annual direct medical costs from annual indirect costs due to loss of work productivity in wages, absence from work, and premature death (Lightwood et al., 2009). The results of their study are startling. In direct medical costs alone, they showed that costs will increase from approximately $130 million in 2020 to over $10 billion by 2050. Even more shocking were their indirect cost estimates. In 2020, projected indirect costs stemming from obesity and obesity-related diseases are $942 million. By 2050 those estimates are expected to rise to $36 billion, a $35 billion dollar increase in 30 years (Figure 2). Ultimately, the study concluded that “most of the projected economic burden consists of indirect costs from lost productivity caused by premature death or absence from work, with direct healthcare costs accounting for only 12 to 21 percent of the total economic burden” (p. 2223).

Figure 2. Direct vs. indirect medical cost projectionsThis study provided important insight into the reactive versus preventive healthcare debate. Reactive measures focus primarily on the direct costs discussed in this model. Although it is apparent that there are direct medical costs stemming from future obesity-related problems, it is the indirect costs associated with the increase in obesity that form the bulk of America’s future financial burdens. Reducing direct medical costs through better and more affordable insurance regulation will help to some degree, but reducing obesity levels seems to be a more effective way to see significant improvement. Perhaps this study provides a good illustration of how much attention government legislators should give to reactive versus preventive measures by looking at direct versus indirect estimated costs respectively.

Does preventive care reduce costs?

Although most Americans agree about the need for some preventive care, it is important to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of the preventive policies themselves. Studies have shown that although some forms of preventable action can save money, others only add to costs (Russell, 2007). In fact, some estimates claim that fewer than 20 percent of preventive options would be cost-saving (Cohen, Neumann, Weinstein, 2008). Whether these estimates nullify the importance of more preventive measures is debatable. Often, a preventive measure’s effectiveness is directly correlated to the population or risk group to which it is applied. One study gave the example of drugs used to treat high levels of cholesterol and illustrated that the drug has a much higher yield in monetary value if the targeted population is at high risk for coronary heart disease (Russell, 1993). In this sense, implementing preventive policies is somewhat hit or miss. If, for example, an anti-obesity ad that attempts to motivate an overweight target group to exercise and eat healthier is shown primarily to an audience who is not overweight and already exercising, the ad will fail to be effective. However, localizing programs to only those at high risk is easier said than done. This substantiates the need for further investigation into forming more effective preventive programs. Fundamentally, government must not only strive for increased preventive programs but smarter ones as well.

Part of the difficulty in establishing good preventive programs is in defining which aspects of prevention should be emphasized. Experts on preventive methods maintain that programs emphasizing medical services (screenings, medicines, doctor visits, etc.) rather than behavioral changes (diet and exercise) are typically more expensive and could increase medical costs (Russell, 2007). It is apparent that even within the category of preventive care itself, some hierarchy of options exists, each having its own benefits or drawbacks in terms of projected costs. However, when speaking of obesity, it is important for the general public to be aware that this disease is not an infection or virus requiring a vaccine; it is almost always self-controllable.

Clear secondary preventive costs like vaccines or cancer screenings are unavoidably associated with other diseases. However, obesity represents a rare prevention category, in that its costs could theoretically be eliminated over time. For example, as people become more aware of and proactively engaged in their own health, a self-promoting culture of exercise and wellness could replace the need for expensive preventive advertising campaigns. Popular chef and media personality, Jamie Oliver, has taken this approach in his recent television show, Jamie Oliver’s Food Revolution (Jamie Oliver’s Platform for Change, 2010). Jamie focuses his work in Huntington, West Virginia, previously rated by the CDC as the unhealthiest city in America, by teaching the residents how to buy and prepare nutritious foods in an attempt to help them implement a self-promoting culture of health and well-being. As of March 23, 2010, Jamie Oliver reported via the Late Show with David Letterman that “since making the show, [Huntington’s] ranking has changed . . . and it’s in seventh place now” (Worldwide Pants Incorporated, 2010). The success of public awareness programs like Oliver’s provides evidence for the self-sustaining possibilities of preventive action.

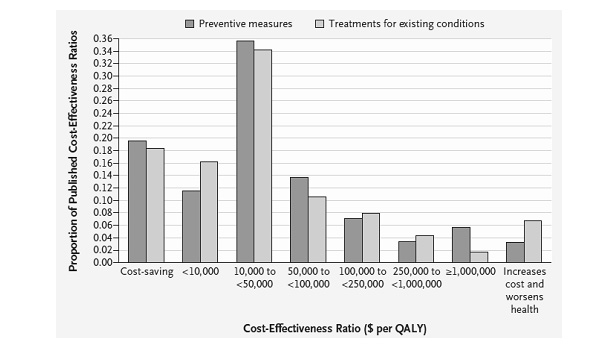

A study published in the New England Journal of Medicine offers a good summary of the overall costs associated with preventive versus reactive programs. In this study, 600 different articles on cost-effectiveness ratios between many different reactive and preventive measures were compiled and charted based on the costs of their quality-adjusted-life-year (QALY). This was a comparison between the costs of a particular intervention and the number of quality life-years that would be added to a patient’s life upon the intervention being implemented (Cohen et. al, 2008, Figure 3).

Figure 3. Cost-effectiveness ratios between preventive measures and treatments for existing condintionsAs indicated from these comparisons, it is apparent that some preventive methods equal or outweigh their reactive counterparts in terms of their cost per quality-adjusted-life-year. Although this may be discouraging for preventive care enthusiasts, it is not altogether conclusive. Most of these studies pertain to secondary prevention measures (reducing the effects of a disease before it becomes dangerous) and tertiary prevention (reversing or slowing the progression of an existing condition) (Marmor et al., 2009). As previously noted, these types of preventions cost significantly more than primary prevention. For example, screening all 65-year-olds for diabetes costs more ($590,000 per QALY) than screening just those with hypertension (Marmor et al., 2009). Still, screenings fall under the category of secondary prevention. Ideally, primary preventive measures would be effective enough to significantly reduce the need for screenings, greatly reducing their costs.

The notion that the effectiveness of a program can be judged solely by its costs is also incorrect. This same study concluded that “the illusion of painless savings . . . confuses our national debate on health reform and makes the acceptance of cost control’s realities all the more difficult” (Marmor et al., 2009, p. 488). In assessing the goals of improved healthcare, one must realize that there are psychological and social benefits available through a preventive lifestyle that cannot be achieved through more reactive methods. Although it is possible that initiating certain preventive measures may cost the same or slightly more than their reactive counterparts up front, prevention will save more money in the long run and is more beneficial to a self-maintained, healthy lifestyle.

Cost-efficient prevention

Although not all preventive programs for obesity are less costly than their reactive counterparts, several are. Evidence suggests that school-based interventions, dietary restrictions, and increased physical activities are all cost-efficient and can significantly reduce obesity.

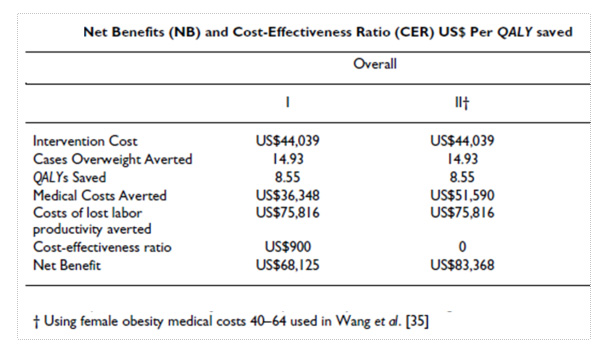

The Coordinated Approach to Child Health (CATCH), a health promotion program, conducted an extensive study in El Paso, Texas that tracked the health-effectiveness and cost-efficiency of a school-based obesity prevention program (Brown et al., 2007). From 2000-2002, faculty from four elementary schools were either hired or given special training in physical education, nutrition, and health promotion. Data were collected as to how many cases of overweight children were averted and how many QALYs were added to the children’s lives. These numbers were then compared with other studies that defined the costs of obesity in terms of lost wages and increased medical costs. Those costs were then subtracted from the total cost of implementing the intervention (hiring faculty, etc.) to project a total net benefit for the program (Brown et al., 2007). Although the intervention cost was calculated at $44,039, the net benefit after subtracting the medical costs and lost wages associated with the potential obesity cases that were averted was estimated at $83,368. In a separate comparison that used more modest estimates of medical costs provided by other studies, the net benefit was recalculated to $68,125 (Brown et al., 2007, Figure 4). Even with the disparity between the two estimates, it is clear that preventive programs such as CATCH are both highly cost-efficient and effective in reducing obesity.

Figure 4. Net Benefits and Cost-Effectiveness Ratio of CATCH Program in El Paso, TX School DistrictSkeptics of such studies might be concerned with the reliability of the data or with its application to the United States as a whole, in that obesity rates are often demographic-specific (with higher rates of obesity often found among lower income families and certain minority groups). Fortunately, this study was purposely conducted in a school district containing 94% Hispanic students (one of the more obese minority groups), so that the effect of the CATCH program could be monitored in an environment ideal for making these changes (Brown et al., 2007). A separate estimate that incorporated the potential lower incomes of Hispanics showed that even with a lower level of lost wages subtracted from the intervention costs, the net benefit of the CATCH program is still $43,000-$58,000, depending on the medical cost estimates used.

Given these findings, if a fairly “obese” state such as Mississippi (which has 3,714 elementary schools) chose to implement the CATCH program state-wide, their net savings would exceed $46 million, even with a very modest estimate of CATCH savings at $50,000 per four schools (Council of Chief State School Officers, 2010). The savings of a nation-wide CATCH program would carry over into the billions of dollars. On a cost factor alone, school-based preventive programs such as CATCH are well worth the investment. When addressing external factors, such as increased quality of life, their importance is even further substantiated.

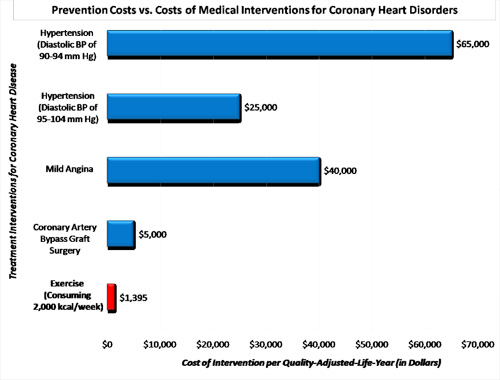

Another health promoting and economical way of preventing obesity-related disease is through exercise. In 1988, researchers analyzed the cost-efficiency of implementing daily exercise by calculating the costs associated with burning 2,000 kcal per week and then comparing those costs to the direct costs of medical treatments for coronary heart disease, a condition commonly associated with obesity and lack of exercise (Hatziandreu, Koplan, Weinstein, Caspersen, & Warner, 1988). In calculating the total direct costs of exercise, they included the price of regular doctors’ visits, which helped implement and maintain a routine exercise program. By doing this, they addressed one of the more difficult issues of attempting to apply preventive programs—changing the behavior of the unhealthy individual. Ultimately, exercise was estimated to cost $1,395 per QALY, whereas a coronary bypass graft or treatment for hypertension was estimated to cost anywhere from $5,000-$65,000 per QALY (Hatziandreu et al., 1988, Figure 5).

Figure 5. Prevention Costs vs. Costs of Medical Interventions for CHDAlthough this study was conducted in the 1980s and current inflation of medical prices would significantly alter these estimates, the cost difference between reactive and preventive interventions would still be relatively proportional to this data. Calculating the savings on a national level is inexact, but a rough estimate can be given using the numbers in this study. Given the CDC’s estimate of 631,636 people dying from heart disease in 2009, and a modestly estimated average savings of $25,000 per QALY per person with coronary problems, affected Americans would save almost $16 billion per QALY if they had chosen to implement weekly exercise rather than incur the medical costs associated with preventable heart problems (CDC, 2010). Keep in mind that this estimate is only for individuals who died last year and in the latest term of their illness.

The American Heart Association estimates that over 17,000,000 victims of heart disease or angina (chest pain ensuing from heart disease) are still living and that over 500,000 new cases of angina surface each year (American Heart Association [AMA], 2010). By taking these active cases into account, the estimated savings would increase more than ten-fold. Either way, it is clear that a preventive exercise approach saves a substantial amount of money. It is important to note that these numbers do not take into account many peripheral factors such as the costs (emotional and financial) associated with getting 630,000 people to start exercising, despite encouraging visits with their doctor. However, it is still necessary to establish the long-term savings potential of preventive methods with the goal that they would one day be somewhat self-maintained.

Although decreasing the obesity levels of millions of Americans may seem like an enormous undertaking, a third area of prevention, maintaining energy balance, focuses primarily on halting these rising rates rather than altogether reversing them. In theory, scientists propose that the only way to gain a firmer grasp on reducing obesity in the long term is to plateau gradual weight gain short term. A study published in Science Magazine addressed these same concerns (Hill, Wyatt, Reed, & Peters, 2003). Researchers were determined to find how many excess calories the average American was consuming per day, and subsequently what action could be taken to eliminate this excess. Their goals were consistent with the tenets of preventive programs. Ultimately, they showed that an average of 90 percent of the population stores an extra 100 kcal per day in their bodies (Hill et al., 2003). They then went on to propose several simple, cost-effective ways to reduce this excess. For example, by eating 15 percent (about 3 bites) less of a typical fast-food hamburger, the excess 100 kcal would be avoided (Hill et al., 2003). Additionally, food packagers and restaurants could reduce their packaging and portion sizes by 10-15 percent to offset the excess calorie intake. If portion control doesn’t appeal to those wishing to drop the excess calorie intake, the study suggests that walking one extra mile a day (about 2000 steps) would adequately expend the excess. In accordance with this concept, Colorado, the state with the lowest obesity rates in the nation, implemented a state-wide program called Colorado on the Move (University of Colorado at Denver and Health Sciences Center [UCDHS], 2004). This program encouraged the reduction of 100 kcal/day per person through widely distributing pedometers that track steps taken throughout the day (UCDHS, 2004).

Many overweight or obese individuals succumb to their disheartening condition and fail to realize the relative ease through which significant weight control can be maintained, as suggested in the aforementioned examples. As government increases attention and funding for preventive movements, a larger percentage of people will realize that the pathway to a healthier lifestyle is well within their reach.

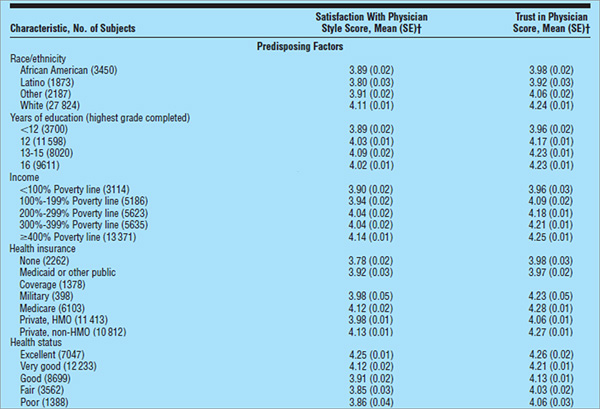

Opposing views of preventive healthcare

Despite the idealistic goals of preventive healthcare, attention should be given to every counter-argument to ensure that intelligent and functional policies are maintained. Most opponents of increased preventive care do not completely deny the need for prevention. Rather, they claim that in order to reduce obesity and its associated healthcare costs, coverage must be extended to lower income households in order to receive preventive instruction and care from the hand of a physician. To a large degree, these concerns are legitimate and emphasize the need for both extended coverage and preventive measures. Some evidence shows a direct relationship between lower household income and higher rates of obesity (Krisberg, 2009). Assuming decreased access to healthcare is attributable to lower incomes, the argument for extended medical coverage holds water. However, the evidence supporting this claim is not conclusive when considering other factors. For example, studies show that the level of patient trust for their doctor declines when there is a decrease in any of the following factors: education, income, amount and type of health insurance, and health status (Doescher, Saver, Franks, & Fiscella, 2000, Figure 6). Furthermore, levels of patient trust for doctors vary according to different ethnicities and are especially low for African-American and Latino groups, which are the two most obese ethnic groups in the United States (Krisberg, 2009).

Relationships Between Satisfaction and Trust of Physician and Selected Patient Characteristics

Figure 6. Relationships Between Physician Trust and Selected Patient CharacteristicsThe lower rate of trust for doctors among people within these different categories weakens the theory that increased coverage would equate to healthier individuals. Patients will respond to their physicians’ preventive suggestions only to the degree that they trust or value the doctors and their advice. In one aspect, the data show a clear relationship between having insurance and trusting doctors, as apparent from non-insurance holders giving an average trust score of 3.98 on a 5-point scale, while patients with private, non-health maintenance organizations (HMO) insurance give a higher average trust rating of 4.27 (Doescher et al., 2000). In this sense, expanding coverage to those without insurance might have a positive outcome in terms of increased doctor trust and subsequent acceptance of preventive instruction. But two problems exist with this hypothesis. First, Medicaid is a common prototype for government-provided insurance and is a useful example in assessing the type of care that would be provided in reforms involving expanded coverage. With this in mind, notice that those with Medicaid coverage gave a doctor trust rating of 3.97, slightly lower than those with no coverage at all (Doescher et al., 2000). If government hopes to promote better doctor-patient relationships by introducing low-cost coverage to the uninsured, there is obviously need to provide them with a new and better service. Second, while extending coverage to those without it may enhance their trust of physicians in one aspect, it fails to address any of the other categories represented in the study. Extending coverage is not going to make someone change ethnicities, increase their years of education, or boost their income. Clearly, there are other reasons besides the issue of coverage that motivate people to choose whether or not to implement advice from their doctors. Furthermore, it seems that those groups of people most prone to obesity (low income, select ethnicities, poorer health, etc.) are least prone to listen to their doctors.

Although some legislators may have good intentions in wanting to extend these individuals greater healthcare coverage, evidence like this raises doubt that some groups of people will actually take advantage of the services they are provided. Some may question how this inconsistency comes about: do people choose not listen to their doctors because they have poorer health, or do they have poorer health because they will not listen to their doctors? Regardless, this is rarely a discussion heard among legislators responsible for forming America’s healthcare policy, yet it is an essential conversation for those who intend to shape reform that actually works. Investigating the reason for these disparities will help government form better health programs and will help doctors form better relationships with their patients. When the goal of improved doctor-patient relationships are factored in to insurance reform, then expanding coverage really becomes a type of preventive measure in itself, and the two opposing sides can collaborate and reach common ground. Ultimately, if government chooses to extend coverage in hopes of preventing disease, they will need to focus more on the success of their programs in aiding prevention and less on how inexpensively they can obtain them.

Looking outside the costs

In order to gain a proper perspective of the various arguments for and against prevention, it is important to remember the origin of those debates—health, not costs. Since 1946, the World Health Organization (WHO) has defined health as “a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being, not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” (International Health Conference, 1946, p. 100). When this broader view of health is considered, the voices of those who oppose preventive care become greatly subdued. In order to abide by the tenets of this definition, Americans need to realize the benefits associated with living a balanced and healthy life, rather than just utilizing the marvels of modern medicine after the fact. Only prevention can accomplish this.

If the definition of “health” includes mental and social well-being, one must also consider studies that look at factors other than costs influenced by the onset of obesity. For example, a study sponsored by the AMA found a direct relationship between obesity and symptoms of depression (J. Dixon, M. Dixon, & O’Brien, 2003). Their data suggest that over 53 percent of obese patients had a Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) score greater than 16, indicating moderate to extreme depression. They ultimately concluded that “symptoms of depression in these obese subjects . . . were strongly associated with poor quality-of-life scores . . . especially those related to social functioning, emotional role, and mental health” (p. 2063). A related study directly linked increased body mass index (BMI) to an increase in suicidal ideation and attempts (Eaton, Lowry, Brener, Galuska, & Crosby, 2005). Although these are obviously extreme side-effects of the obesity epidemic, they must be given consideration in the preventive healthcare debate.

These findings reiterate the fact that there is no substitute for a healthy lifestyle. It is true that reactive medicine is a medium for healing and comfort to millions of suffering Americans, and as such, should be honored, invested in, and continued. But the restorative capabilities of modern medicine do not justify the onset of diseases that are preventable or the propagation of a low quality life.

Creating a prevention-based mindset—the future of healthcare

Changing the behavior of millions of Americans is not going to be accomplished merely through strategic legislation. In reality, such a change cannot come from any one office or program. Indeed, changing the behavior of millions of Americans requires just that—millions of Americans. Perhaps the answer to America’s healthcare issue does not lie in a change of policy but in a change of mindset. Efforts need to be made on every level to establish a culture of health promotion and disease prevention. Current norms about body image, for example, are destructive to the goals of prevention. The U.S. government, the public, and the scientific community could all benefit from a refreshed view of what it means to be healthy.

One small example of how Americans might change their viewpoints is demonstrated by the way Singapore chooses to define weight norms. Instead of labeling weight categories with terms like “overweight” and “obese,” Singapore labels their BMI cutoffs in terms of potential risks with categories such as “high risk” or “low risk” for heart disease or other health problems (Misra, 2003). Although these labels are not overly encouraging to those who are obese, at least they communicate the real risks and consequences associated with the individual’s behavior. These classifications are proactive in nature and encourage patients to be proactive as well by educating them about the risks they face and then motivating them to make necessary changes. The American system, on the other hand, leaves the obese individual with nothing more than the knowledge that one more doctor or professional is confirming what they probably already knew—they are unhealthy. Although Singapore’s model may be just a minute example of a preventive attitude, it is a powerful one.

Although establishing an enhanced affinity for health and wellness sounds ideal, one question remains unanswered—just what is government’s role in seeking this goal? The catalyst for a changing America is much stronger with the synergistic cooperation of its population than with simply the voice of a few government officials. To that end, the U.S. government has the responsibility to effectively publicize and promote the need for cooperative and united citizens in this cause. The fight against obesity requires wise stewardship and government legislators who resist the urge for “quick fixes” or short-term answers only. Just as individual weight loss is a gradual, often painful, time-consuming process, so is the road to its implementation nation-wide. Increasing funding, attention, and awareness of a preventive lifestyle is the only responsible pathway to that goal. As America faces a dawn of difficult change and decision-making, government’s role is essentially the same as it has always been: to promote rather than provide; to persuade rather than prescribe; and to prevent rather than to predestine.

References

American Heart Association, (2010). Preventive Health Care. Retrieved from http://www.americanheart.org/ presenter.jhtml?identifier=4591

Brown, H. S., Perez, A., Li, Y. P., Hoelscher, D. M., Kelder, S. H., & Rivera, R. (2007). The cost-effectiveness of a school-based overweight program. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 4:47 doi:10.1186/1479-5868-4-47

Budget of the U.S. Government, (Fiscal Year 2010). Historical Tables, table 16.1, p. 334. Retrieved from http://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget/Historicals/

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, (2010). Overweight and Obesity. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/index.html

Cohen, J. T., Neumann, P. J., & Weinstein, M. C. (2008). Does preventive care save money? health economics and the presidential candidates. The New England Journal of Medicine, 358 (7), 661-663.

Congressional Budget Office, (2010). H.R. 4872, Reconciliation Act of 2010. Retrieved from http://www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/113xx/doc11379/Manager%27sAmendmenttoReconciliationProposal.pdf

Council of Chief State School Officers, (2010). School Matters. Retrieved from http://www.schoolmatters.com

Derthick, M. (1979). Policymaking for social security. Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution.

Dixon, J. B., Dixon, M. E., & O’Brien, P. E. (2003). Depression in association with severe obesity changes with weight loss. Archives of Internal Medicine, 163 (17), 2058-2065.

Doescher, M. P., Saver, B. G., Franks, P., & Fiscella, K. (2000). Racial and ethnic disparities in perceptions of physician style and trust. Archives of Family Medicine, 9, 1156-1163.

Eaton, D. K., Lowry, R., Brener, N. D., Galuska, D. A., & Crosby, A. E. (2005). Associations of body mass index and perceived weight with suicide ideation and suicide attempts among

US high school students. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 159, 513-519.Hatziandreu, E. I., Koplan, J. P., Weinstein, M. C., Caspersen, C. J., Warner, K.E. (1988). A cost-effectiveness analysis of exercise as a health promotion activity. American Journal of Public Health, 78, 1417-1421.

Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, (2010). Side-by-Side Comparison of Major Health Care Reform Proposals. Retrieved from http://www.kff.org/healthreform/upload/housesenatebill_final.pdf

Hill, J. O., Wyatt, H. R., Reed, G. W., & Peters, J. C. (2003). Obesity and the environment: where do we go from here? Science Magazine, 299 (5608), 853-855.

International Health Conference (1946). Preamble to the Constitution of the World Health Organization. Official Records of the World Health Organization, 2, 100.

Jamie Oliver’s Platform for Change, (2010). Retrieved from http://www.jamieoliver.com/jfr-beta/pdf/Jamie-Oliver_Platform-for-change.pdf

Krisberg, K. (2009). U.S. obesity trends are growing worse, adding to health costs. Nation's Health, 39 (7), 6-6.

Lightwood, J., Bibbins-Domingo, K., Coxson, P., Wang, Y. C., Williams, L., & Goldman, L. (2009). Forecasting the future economic burden of current adolescent overweight: An estimate of the coronary heart disease policy model. American Journal of Public Health, 99 (12), 2230-2237.

Marmor, T., Oberlander, J., & White, J. (2009). The Obama administration’s options for health care cost control: Hope versus reality. Annals of Internal Medicine, 150, 485-489.

Misra, A. (2003).Revisions of cutoffs of body mass index to define overweight and obesity are needed for the Asian-ethnic groups. International Journal of Obesity, 27, 1294–1296. doi:10.1038/sj.ijo.0802412

Myers R. (1967). Actuarial cost estimates for the old-age, survivors, disability, and health insurance system as modified by the social security amendments of 1967. committee print, committee on ways and means, House of Representatives, 90th Congress, 1st Session; December 11, 1967.

National Center for Health Statistics (2002). National health and nutritional examination survey. United States. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/overweight/overweight_adult.htm

Russell, L.B. (1993) The role of prevention in health reform. New England Journal of Medicine, 329, 352-354.

Russell, L.B. (2007). Prevention’s potential for slowing the growth of medical spending. National Coalition on Health Care, Washington D.C. 2007.

University of Colorado at Denver and Health Sciences Center, (2004). Colorado on the Move. Retrieved from http://www.uchsc.edu/nutrition/Coloradoonthemove/com.htm

Worldwide Pants Incorporated (2010, March 23). Interview with Jamie Oliver. The late show with David Letterman. New York, NY: CBS, Inc.

|