Eye Deceptions: The Evolution Of George D. Greenís Painting

From The Late 1970s To The Present

Dalton, Kristin (Fine Arts)

Fritz, Katie (Graphic Design)

Klein, Dustin (Graphic Design)

Meyer, Rachelle (Graphic Design)

Schanzenbach, Luke (Graphic Design)

South Dakota State University – Spring 2008

Course: ARTH 490 – Seminar BETWEEN OBJECT AND PROCESS

Guest Editor and Project Coordinator: Dr. Leda Cempellin, Art Historian

All the images of paintings by George D. Green are reproduced courtesy of the artist. Our sincere gratitude to Dr. Dorothy I. Mitstifer for the final revision of this essay and to Louis K. Meisel for his interest in scholarly projects on this artist.(Click images to view larger version. Javascript required.)

Introduction. After Pollock: George Green’s Method, Between Object And ProcessGeorge Green’s style was established early on in his career as having both abstract and realistic concerns; one cannot exist without the other:

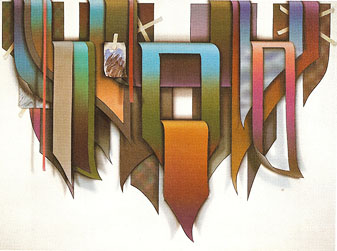

The co-presence of abstract and trompe-l’oeil qualities in George Green’s work are groundbreaking; indeed, since the late 1970s, Green’s style has been categorized, together with a number of other artists, as abstract illusionist. Although Green’s style has progressed and grown, his early pieces show incredible technical painting skills, along with strong compositional qualities. All his pieces use layering and shadow effects to create depth and the illusion of a three-dimensional plane. Green uses abstract shapes rendered in a realistic style, which creates both cohesion and contradiction. His painting style also switches throughout each piece from glazing to heavy impasto strokes. The glazing effect adds to the realistic style, whereas the impasto adds a three-dimensional sculptural effect. Much like the early Abstract Expressionists, Green pushes the boundaries of a two-dimensional painting surface and changes it into a three-dimensional object. When Jackson Pollock painted ( Fig. 51: http://bcm.bc.edu/wp-content/images/summer_2007/for-arts-sake-1.jpg ), he would place his large canvas on the floor, so he could work from every edge and view of the painting; Pollock would then use brushes, sticks, and other objects to drip, throw, splash, or pour paint onto the canvas. Pollock was able to move into his paintings and use his whole body to paint, “working on impulse and with irrational desire rather than to a plan or a specific image” (Lynton 143). Pollock looked at his paintings as a relic of the actions that generated it and felt “his paintings were a direct and fresh expression of the inner life that impels all artists” (Zelanski and Fisher 481). By painting without a desired, predetermined idea of what the end product will be, Pollock let his painting take on a life of its own ( Fig. 50: http://2modern.blogs.com/photos/uncategorized/jackson_pollock_1.jpg), making decisions about the next step of the painting at the instant when the possible course of action presents itself. Painting on instinct and instantly, “Pollock felt, he could become emotionally at one with his work and through it communicate his emotions to the viewer” (Janson et al.139). George Green is not an Action Painter in the way that Jackson Pollock was, but his method of evolving his paintings over time resembles the methods of the Action Painters. Indeed, when Green was twelve years of age and living in Corvallis, Oregon, he began “making pictures . . . just shapes and colors (no subject matter), pictures about the activity of making pictures” (Green 2/16/08). Years later, after making some important discoveries that led him to Untitled #9 ( Fig. 1), Green started a new phase of “frantic action followed by a life changing reflective phase, followed by the resumption of frantic action” (Green 2/16/08). Green felt that he had discovered a new skill to use in his pictures and at the same time felt that no gallery would show his work. Yet he continued his “frantic actions . . . working in a state of high-energy flow, seemingly continuously on automatic pilot” (Green 2/16/08), for two days and nights. Similarly to Pollock, Green achieves an overall sense of harmony in his paintings, despite the high level of energy. Green explained this paradox in these terms:

Even though Pollock may have been indebted to preceding styles, “the directness with which he permitted his unconscious to determine the form of this painting had no art historical precedent” (Fineberg 86). There is much to be said about this lack of “art historical precedent.” Green’s risk-taking is reminiscent of Pollock’s lack of regard for historical and cultural precedents: “If you make pictures, all manner of opportunities will present themselves and mostly go unnoticed or suffer rejection from acquiescence to cultural orthodoxies” (Green 2/28/08). Pollock was not concerned with the effect art had on others. It was an experience specific to him, just as Green’s “pictures” are specific to his visual challenges. As we will see throughout this essay, this characteristic qualifies Green’s painting as maturely postmodern. Therefore, by looking at the methods of Jackson Pollock and George Green, one can see that the ideas behind the motivation are very similar; Green described his method as “one thing leading to another, morphing into stream of consciousness activity. Doing before thinking, the unconscious mind taking the lead” (Green 2/16/08); and Pollock said: “I’m not aware of what I’m doing… I have no fears about making changes, destroying the image, etc., because the painting has a life of its own. I try to let it come through” (qtd. In Lynton 143).

|

||

|